|

|

Tarquinia |

|

|

Tarquinia is een stadje in de Italiaanse provincie Viterbo. Het heeft een goed bewaarde binnenstad, met kerken uit de 13de en paleizen uit de 13de en 15de eeuw, een castello, en een belangrijk archeologisch museum. Maar Tarquinia is vooral bekend voor zijn necropolis, die deel uitmaakt van de werelderfgoedlijst van de Unesco. De Etruskische necropolis omvat 6000 graven, waarvan 200 beschilderd zijn met schitterende fresco’ s. De necropolis van Tarquinia is omwille van de vele fresco's van uitzonderlijk belang voor onze kennis van het dagelijks leven van de rijke klasse in de Etruskische maatschappij. De belangrijkste site is de necropolis van Monterozzi. |

|

Chiesa di Santa Maria in Castello |

Geschiedenis en bezienswaardigheden Ten noordoosten van het hedendaagse Tarquinia en het vroegere Corneto ligt de Etruskische stad Tarquinii, die onder de naam Turchuna een van de belangrijkste leden was van het twaalfstedenverbond.

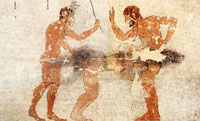

De necropolis van Tarquinia De Etruskische necropolis omvat 6.000 graven, waarvan 200 fresco's bevatten. De belangrijkste site is de Necropolis van Monterozzi, met een groot aantal tumulus graven, waarvan de kamers in de rots zijn uitgehouwen. De taferelen op de fresco's tonen banketten met dans en muziek, sportieve spelen en af en toe erotische of mythologische scènes. De bekendste graven zijn het Graf van het Triclinium, het Graf van de Stieren, het Graf van de Auguren en het Graf van de Luipaarden. Het Graf der Auguren (circa 530 v. Chr.) toont een muurschildering van worstelaars die vechten voor waardevolle prijzen, zoals metalen kommen. Een andere scène in hetzelfde graf laat een man met een knuppel zien; hij heeft een zak over het hoofd en moet zich verdedigen tegen een wilde hond, die door een gemaskerde wordt opgehitst. Mogelijk stamt dit bloedig spel af van rituele mensenoffers bij de begrafenis van koningen in een zeer ver verleden. De Etrusken, in het voor-Romeinse Italië, hadden zeer lang een eigen cultuur. Ze woonden in het huidige Toscane en Umbrië. Tegenwoordig gaan we ervan uit dat de Etrusken een autochtoon, pre-Indoeuropees volk zijn. Tarquinia heeft één van de belangrijkste archeologische musea in de omgeving dat is gehuisvest in Palazzo Vitelleschi. De begane grond bevat onder andere een serie sarcofagen met waardevolle grafbeelden uit de 4e tot 1ste eeuw v.o.t.. Vanaf het centrum naar de Etruskenstad Tarquinia, is slechts tien kilometer. Tarquinia Monterozzi necropolis, area of Calvario |

||||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

| The archaeology of Tarquinia has been at the forefront of Etruscan studies since the early days of antiquarian scholarship and is renowned for its unique painted tombs and vast cemeteries, and attracted eminent writers and poets, among them Stendhal, D.H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley and Malaparte. Among the famous writers drawn to Tarquinia's enigmatic Etruscan past, its legends, and cultural heritage were Stendhal, D.H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley and Malaparte. Henri Bleyle Stendhal, the great 19th-century French novelist who penned The Red and the Black, was for a time a diplomat in Rome. He became enchanted with Tarquinia, then known as Corneto, and authored a long article about its recently discovered Etruscan tombs. In early April 1927 D.H. Lawrence embarked on what was to be his last extended walking tour. Accompanied by his friend Earl Brewster, he visited the major sites associated with the Etruscans, from Volterra in the north of Tuscany to Tarquinia. |

||||

The Tomb of the Leopards is a charming, cosy little room, and the paintings on the walls have not been so very much damaged. All the tombs are ruined to some degree by weather and vulgar vandalism, having been left and neglected like common holes, when they had. been broken open again and rifled to the last gasp. |

|

|||

| Tarquinia | The Necropolises of Tarquinia and Cerveteri Tarquinia | The Tomba delle Leonesse, at Tarquinia (The Tomb of the Lionesses) |

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

|

Enlarge map |

||||

|

|

||||

| Tarquinia | ||||