| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| Pisa, Piazza dei Miracoli

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Tuscan art cities | Pisa, the Piazza dei Miracoli

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Tuscany is known for its gorgeous landscapes, its rich artistic legacy and vast influence on high culture. Tuscany is widely regarded as the true birthplace of the Italian Renaissance, and has been home to some of the most influential people in the history of arts and science, such as Petrarch, Dante, Botticelli, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo Galilei, Amerigo Vespucci, Luca Pacioli and Puccini.

Six Tuscan localities have been designated World Heritage Sites: the historic centre of Florence (1982), the historical centre of Siena (1995), the historical centre of San Gimignano (1990), the historical centre of Pienza (1996), the Val d'Orcia (2004) and the square of the Cathedral of Pisa, the Piazza dei Miracoli (1987).

Pisa is the city of the lungarni (the banks of the river Arno), much loved by romantics poets for its climate and traditions of tolerance: from Byron to Shelley, from Giacomo Leopardi to Alessandro Manzoni. With extraordinary effectiveness, the phrase Piazza dei Miracoli (the Miracle Square), coined by Gabriele D'Annunzio, epitomises the amazement and admiration that for centuries have seized those who, upon passing through the gateway of the circle of walls or emerging sideways from Via S. Maria, embrace in one single glance the pure whiteness of the monuments rising over the lush green of the turf.

One is also amazed by the unique isolation of this group of monuments: the large area where the sacred buildings rise is actually on the edges of town, in the north-western corner, looking almost proud and distant from the daily bustle of the town.

The name Piazza dei Miracoli was created by the Italian writer and poet Gabriele d'Annunzio who, in his novel Forse che si forse che no (1910) described the square in this way:

L’Ardea roteò nel cielo di Cristo, sul prato dei Miracoli.

which means: "The Ardea rotated over the sky of Christ, over the meadow of Miracles."

Since 1987, the group of monuments of Piazza del Duomo di Pisa has been declared World Heritage by UNESCO.

|

|

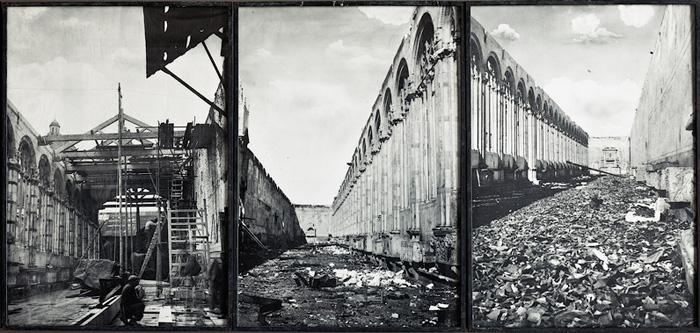

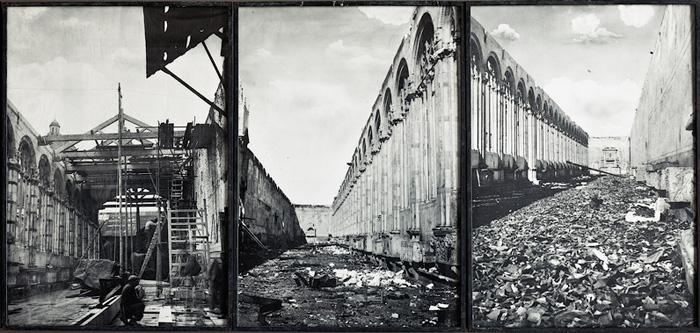

Pisa, Piazza dei Miracoli, 1931 [Archivio Storico Famiglia Gen. Enrico Pezzi]

|

While the Leaning Tower is the most famous image of the city, it is one of many works of art and architecture in the city's Piazza del Duomo, also known, since 20th century, as Piazza dei Miracoli (Square of Miracles), to the north of the old town center. The Piazza del Duomo also houses the Duomo (the Cathedral), the Baptistry and the Camposanto Monumentale (the monumental cemetery).

Other interesting sights include:

* Knights' Square (Piazza dei Cavalieri), where the Palazzo della Carovana, with its impressive façade designed by Giorgio Vasari may be seen.

* In the same place is the church of Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri, also by Vasari. It had originally a single nave; two more were added in the 17th century. It houses a bust by Donatello, and paintings by Vasari, Jacopo Ligozzi, Alessandro Fei, and Jacopo Chimenti da Empoli. It also contains spoils from the many naval battles between the Cavalieri (Knights of St. Stephan) and the Turks between the 16–18th century, including the Turkish battle pennant hoisted from Ali Pacha's flagship at the 1571 Battle of Lepanto.

* Also close to the square is the small church of St. Sixtus. It was formally consecrated in 1133, but previously used as a seat of the most important notarial deeds of the town, also hosting the Council of Elders. It is today one of the best preserved early Romanesque buildings in town.

* The church of St. Francis, designed by Giovanni di Simone, built after 1276. In 1343 new chapels were added and the church was elevated. It has a single nave and a notable belfry, as well as a 15th-century cloister. It houses works by Jacopo da Empoli, Taddeo Gaddi and Santi di Tito. In the Gherardesca Chapel are buried Ugolino della Gherardesca and his sons.

* Church of San Frediano, built by 1061, has a basilica interior with three aisles, with a crucifix from the 12th century. 16th century paintings were added during a restoration, including works by Ventura Salimbeni, Domenico Passignano, Aurelio Lomi, and Rutilio Manetti.

* Church of San Nicola, built by 1097, was enlarged between 1297 and 1313 by the Augustinians, perhaps by the design of Giovanni Pisano. The octagonal belfry is from the second half of the 13th century. The paintings include the Madonna with Child by Francesco Traini (14th century) and St. Nicholas Saving Pisa from the Plague (15th century). Noteworthy are also the wood sculptures by Giovanni and Nino Pisano, and the Annunciation by Francesco di Valdambrino.

* The small church of Santa Maria della Spina, attributed to Lupo di Francesco (1230), is another excellent Gothic building.

* The chiesa di San Paolo a Ripa d'Arno, founded around 952 and enlarged in the mid-12th century along lines similar to those of the Cathedral. It is annexed to the Romanesque Chapel of St. Agatha, with an unusual pyramidal cusp or peak.

* The Borgo Stretto, a neighborhood where one can stroll beneath medieval arcades and the Lungarno, the avenues along the river Arno. It includes the Gothic-Romanesque church of San Michele in Borgo (990). Remarkably, there are at least two other leaning towers in the city, one at the southern end of central Via Santa Maria, the other halfway through the Piagge riverside promenade.

* The Medici Palace, once a possession of the Appiano family, who ruled Pisa in 1392–1398. In 1400 the Medici acquired it, and Lorenzo de' Medici sojourned here.

* The Orto botanico di Pisa is Europe's oldest university botanical garden.

* The Palazzo Reale ("Royal Palace"), once of the Caetani patrician family. Here Galileo Galilei showed to Grand Duke of Tuscany the planets he had discovered with his telescope. The edifice was erected in 1559 by Baccio Bandinelli for Cosimo I de Medici, and was later enlarged including other palaces.

* Palazzo Gambacorti, a Gothic building of the 14th century, is now the town hall. The interior shows frescoes boasting Pisa's sea victories.

* Palazzo Agostini, a Gothic building also known as Palazzo dell'Ussero, with its 15th century façade and remains of the ancient city walls dating back to before 1155. The name of the building comes from the coffee rooms of Caffè dell’Ussero, historic meeting place founded on 1 September 1775.

* The mural Tuttomondo, the last public work of Keith Haring, on the rear wall of the convent of the Church of Sant'Antonio, painted in June 1989. |

Duomo

|

|

|

The heart of the Piazza del Duomo is, obviously, the Duomo, the medieval cathedral, entitled to Santa Maria Assunta (St. Mary of the Assumption). This is a five-naved cathedral with a three-naved transept. The church is known also as the Primatial, the archbishop of Pisa being a Primate since 1092.

Construction was begun in 1064 by the architect Busketo, and set the model for the distinctive Pisan Romanesque style of architecture. The mosaics of the interior, as well as the pointed arches, show a strong Byzantine influence.

The façade, of grey marble and white stone set with discs of coloured marble, was built by a master named Rainaldo, as indicated by an inscription above the middle door: Rainaldus prudens operator.

The massive bronze main doors were made in the workshops of Giambologna, replacing the original doors destroyed in a fire in 1595. The central door was in bronze and made around 1180 by Bonanno Pisano, while the other two were probably in wood. However worshippers never used the façade doors to enter, instead entering by way of the Porta di San Ranieri (St. Ranieri's Door), in front of the Leaning Tower, made in around 1180 by Bonanno Pisano.

Above the doors there are four rows of open galleries with, on top, statues of Madonna with Child and, on the corners, the Four evangelists.

Also in the façade we can find the tomb of Busketo (on the left side) and an inscription about the foundation of the Cathedral and the victorious battle against Saracens.

At the east end of the exterior, high on a column rising from the gable is a modern replica of the Pisa Griffin, the largest Islamic metal sculpture known, the original of which was placed there probably in the 11th or 12th century, and is now in the Cathedral Museum.

The interior is faced with black and white marble and has a gilded ceiling and a frescoed dome. It was largely redecorated after a fire in 1595, which destroyed most of the medieval art works.

Fortunately, the impressive mosaic, in the apse, of Christ in Majesty, flanked by the Blessed Virgin and St. John the Evangelist, survived the fire. It evokes the mosaics in the church of Monreale, Sicily. Although it is said that the mosaic was done by Cimabue, only the head of St. John was done by the artist in 1302 and was his last work, since he died in Pisa in the same year. The cupola, at the intersection of the nave and the transept, was decorated by Riminaldi showing the ascension of the Blessed Virgin.

Galileo is believed to have formulated his theory about the movement of a pendulum by watching the swinging of the incense lamp (not the present one) hanging from the ceiling of the nave. That lamp, smaller and simpler than the present one, it is now kept in the Camposanto, in the Aulla chapel.

The impressive granite Corinthian columns between the nave and the aisle came originally from the mosque of Palermo, captured by the Pisans in 1063.

The coffer ceiling of the nave was replaced after the fire of 1595. The present gold-decorated ceiling carries the coat of arms of the Medici.

The elaborately carved pulpit (1302-1310), which also survived the fire, was made by Giovanni Pisano and is one the masterworks of medieval sculpture. It was packed away during the redecoration and was not rediscovered and re-erected until 1926. The pulpit is supported by plain columns (two of which mounted on lions sculptures) on one side and by caryatids and a telamon on the other: the latter represent St. Michael, the Evangelists, the four cardinal virtues flanking the Church, and a bold, naturalistic depiction of a naked Hercules. A central plinth with the liberal arts supports the four theological virtues.

The present day reconstruction of the pulpit is not the correct one. Now it lies not in the same original position, that was nearer the main altar, and the disposition of the columns and the panels are not the original ones. Also the original stairs (maybe in marble) were lost.

The upper part has nine panels dramatic showing scenes from the New Testament, carved in white marble with a chiaroscuro effect and separated by figures of prophets: Annunciation, Massacre of the Innocents, Nativity, Adoration of the Magi, Flight into Egypt, Crucifixion, and two panels of the Last Judgement.

The church also contains the bones of St Ranieri, Pisa's patron saint, and the tomb of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII, carved by Tino da Camaino in 1315. That tomb, originally in the apse just behind the main altar, was disassembled and changed position many times during the years for political reasons. At last the sarcophagus is still in the Cathedral, but some of the statues were put in the Camposanto or in the top of the façade of the church. The original statues now are in the Museum of the Opera del Duomo.

|

|

Coffer ceiling (with coat of arms of the Medici) of the cathedral, Pisa

Dome depicting the Ascension of the Blessed Virgin by Riminaldi; cathedral, Pisa. Equally seen is "the lamp of Galileo" (leading him to invent the law of the isochrony of the pendulum), work by Vincenzo Possenti in 1586

|

Baptistery

|

|

|

The Baptistery, dedicated to St. John the Baptist, stands opposite the west end of the Duomo. The round Romanesque building was begun in the mid 12th century: 1153 Mense August fundata fuit haec ("In the month of August 1153 was set up here..."). It was built in Romanesque style by an architect known as Diotisalvi ("God Save You"), who worked also in the church of the Holy Sepulchre in the city. His name is mentioned on a pillar inside, as Diotosalvi magister. the construction was not, however, finished until the 14th century, when the loggia, the top storey and the dome were added in Gothic style by Nicola Pisano and Giovanni Pisano.

It is the largest baptistery in Italy. Its circumference measures 107.25 m. Taking into account the statue of St. John the Baptist (attributed to Turino di Sano) on top of the dome, it is even a few centimetres higher than the Leaning Tower.

The portal, facing the façade of the cathedral, is flanked by two classical columns, while the inner jambs are executed in Byzantine style. The lintel is divided in two tiers. The lower one depicts several episodes in the life of St. John the Baptist, while the upper one shows Christ between the Madonna and St John the Baptist, flanked by angels and the evangelists.

The immensity of the interior is overwhelming, but it is surprisingly plain and lacks decoration. It has notable acoustics also.

The octagonal font at the centre dates from 1246 and was made by Guido Bigarelli da Como. The bronze sculpture of St. John the Baptist at the centre of the font, is a remarkable work by Italo Griselli.

The pulpit was sculpted between 1255-1260 by Nicola Pisano, father of Giovanni Pisano, the artist who produced the pulpit in the Duomo. The scenes on the pulpit, and especially the classical form of the naked Hercules, show at best Nicola Pisano's qualities as the most important precursor of Italian renaissance sculpture by reinstating antique representations. Therefore, surveys of the Italian Renaissance usually begin with the year 1260, the year that Nicola Pisano dated this pulpit.

|

|

Baptistery

Leaning Tower Leaning Tower

|

Bell Tower or Leaning Tower of Pisa

|

|

The campanile (bell tower) is located behind the cathedral. The last of the three major buildings on the piazza to be built, construction of the bell tower began in 1173 and took place in three stages over the course of 177 years, with the bell-chamber only added in 1372. Five years after construction began, when the building had reached the third floor level, the weak subsoil and poor foundation led to the building sinking on its south side. The building was left for a century, which allowed the subsoil to stabilise itself and prevented the building from collapsing. In 1272, to adjust the lean of the building, when construction resumed, the upper floors were built with one side taller than the other. The seventh and final floor was added in 1319. By the time the building was completed, the lean was approximately 1 degree, or 2.5 feet (0.8m) from vertical. At its greatest, measured prior to 1990, the lean measured approximately 5.5 degrees. As of 2010, this has been reduced to approximately 4 degrees.

|

|

Campo Santo

|

The Campo Santo, also known as camposanto monumentale ("monumental cemetery") or camposanto vecchio ("old cemetery"), lies at the northern edge of the Square. It is a walled cemetery, which many claim is the most beautiful cemetery in the world. It is said to have been built around a shipload of sacred soil from Golgotha, brought back to Pisa from the Fourth Crusade by Ubaldo de' Lanfranchi, archbishop of Pisa in the 12th century, hence the name "Campo Santo" (Holy Field).

The building itself dates from a century later and was erected over the earlier burial ground. The building of this huge, oblong Gothic cloister began in 1278 by the architect Giovanni di Simone. He died in 1284 when Pisa suffered a defeat in a naval battle of Meloria against the Genoans. The cemetery was only completed in 1464. The outer wall is composed of 43 blind arches. There are two doorways. The one on the right is crowned by a gracious Gothic tabernacle. It contains the Virgin Mary with Child, surrounded by four saints. It is the work from the second half of the 14th century by a follower of Giovanni Pisano. Most of the tombs are under the arcades, although a few are on the central lawn. The inner court is surrounded by elaborate round arches with slender mullions and plurilobed tracery.

It contained a huge collection of Roman sculptures and sarcophagi, but now there are only 84 left. The walls were once covered in frescoes, the first were applied in 1360, the last about three centuries later. The Stories of the Old Testament by Benozzo Gozzoli (15th century) were situated in the north gallery, while the south arcade was famous for the Stories of the Genesis by Piero di Puccio (end 15th century). The most remarkable fresco is the realistic The Triumph of Death, the work of Buonamico Buffalmacco. But on 27 July 1944 incendiary bombs dropped by Allied aircraft set the roof on fire and covered them in molten lead, all but destroying them. Since 1945 restoration works have been going on and now the Campo Santo has been brought back to its original state.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Francesco Traini or Buonamico Buffalmacco, Triumph of Death, fresco, (detail, lower left corner).

This section of the painting refers to the medieval tale of "The Three Living and Three Dead."

|

| |

|

|

Most scholars attribute many of the huge frescoes of the Camposanto Monumentale in Pisa to Francesco Traini, including the Last Judgement, Inferno, Legends of the Hermits and, the famous Il Trionfo della Morte (the Triumph of Death). Francesco Traini was an Italian painter active between 1321 to 1365. [1] Other scholars attribute this last work to Buonamico Buffalmacco. [2]

The Trionfo della Morte (after 1350) is considered one of the finest and most powerful artworks of the Trecento as it displays the merciless omnipresence of death. The celebrated frescoes, the Triumph of Death, with accompanying scenes of the Last Judgment, Hell, and Legends of the Hermits were attributed for long time to Francesco Traini. These, among the outstanding Italian paintings of the 14th century, were badly damaged by bombs in the Second World War, but this brought to light, by way of partial compensation, the beautiful 'sinopie, which are now shown in the Museo delle Sinopie. The frescoes include many telling details of death's victims and are usually seen as a reflection of the horrors of the Black Death of 1348, but some authorities consider them earlier and attribute them to the mysterious Buffalmacco.[3]

|

|

Leo von Klenze, The Camposanto in Pisa, 1858, New Pinacothek of Munich [5]

Over the centuries, the Camposanto became the cultural center of Pisa and the region. Many were buried there, and priceless Roman sarcophagi and statues, along with biblical relics, were housed there. The walls were completely decorated in immaculate frescos, and were beautiful beyond description. In short, the Camposanto was the one of the most important and priceless historical structures in all of Italy. The painting seen here shows how it looked.

On July 27, 1944, a wayward Allied bombs started a fire nearby that quickly spread to the Camposanto. The wooden rafters burst into flame and melted the lead on the roof, which dripped down and completely destroyed everything inside.

|

| |

| |

|

Pisa, Palazzo della Carovana on the Piazza dei Cavalieri

|

Palazzo della Carovana (also Palazzo dei Cavalieri) is a palace in Knights' Square, presently housing the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa.

It was built in 1562–1564 by Giorgio Vasari for the headquarters of the Knights of St. Stephen, as a renovation of the already existing Palazzo degli Anziani ("Palace of the Elders"). The name, meaning "Palace of the Convoy", derives from the three year period undertaken by the initiates of the Order for their training, called "la Carovana".

The façade is characterized by a complex scheme with sgraffiti representing allegorical figures and zodiacal signs, designed by Vasari himself and sculpted by Tommaso di Battista del Verrocchio and Alessandro Forzori, coupled to busts and marble crests. The current paintings date however to the 19th-20th centuries.

Amongst the sculptures are the Medici Coat of Arms and that of the Knights, flanked by the allegories of Religion and Justice by Stoldo Lorenzi (1563). The upper gallery of busts of the Grand Dukes of Tuscany were added in the late 16th-early 18th centuries, sculpted by Ridolfo Sirigatti, Pietro Tacca and Giovan Battista Foggini.

The double-ramp staircase was remade in 1821. The rear area is a modern addition (1928–1930) for the Scuola Normale di Pisa. Some halls of the interior house 16th century paintings.

|

The small Church of Santa Maria della Spina is a remarkable example of Pisan Gothic architecture. The church, erected in 1230, was originally known as Santa Maria di Pontenovo: the new name of Spina ("thorn") derives from the presence of a thorn allegedly part of the crown dressed by Christ on the Cross, brought here in 1333. In 1871 the church was dismantled and rebuilt on a higher level due to dangerous inflitration of water from the Arno river: the church was slightly altered in the process, however.

The church is one of the most outstanding Gothic edifices of Europe: it has a rectangular plant, with an external facing wholly composed of marble, laid in polychrome bands. The exterior appearance is marked by cusps, tympani and tabernacles, together with a complicated sculpture decoration with tarsiae, rose-windows and numerous statues from the main Pisane artists of the 14th century. These include Lupo di Francesco, Andrea Pisano with his sons Nino and Tommaso, and Giovanni di Balduccio.

The façade has two gates with lintelled archs. Among these lies the tabernacle with the statues of Madonna with the Child and two Angels, attributed to Giovanni Pisano. Two niches open in the upper part of the façade: these houses the statue of Christ among the two Annunciation ones, and two other angels.

The right side has also a rich decoration with cusps and thirteen statues of the Apostles and Christ, from Lupo's workshop. The small sculptures portraying Saints and Angels over the tympani are from Nino Pisano's workshop, while the niche in the right pillar has a Madonna with Child by Giovanni di Balduccio.

The back side has three round archs with simple windows. The tympani are decorated with the Evangelists' symbols, intervalled by niches with the statues of the Saints Peter, Paul and John the Baptist. The high pyramid-like spires end with the statues of the Madonna with Child between two angels, by Nino Pisano.

If compared to the rich exterior, the interior appears quite simple. It has a single room, with a ceiling painted during the 19th century reconstruction. In the presbytery's centre is one of the highest masterpieces of Gothic sculpture, the Madonna of the Rose by Andrea and Nino Pisano. On the left wall is the tabernacle in which once was the crown's relic, by Stagio Stagi (1534). Another statue by the Pisanos, the Madonna del Latte, was once here, but has been moved to the city's St. Matthew Museum.

Opening Hours - The Church of Santa Maria della Spina

|

|

Santa Maria della Spina |

The church of San Paolo a Ripa d'Arno church in Pisa is one of the most outstanding Romanesque churches in Tuscany. The church is also locally known as Duomo vecchio (old cathedral).

Reports of the founding of the church trace to around 925, but by 1032, a church structure existed. By 1092, the church was annexed to a monastery of the Vallumbrosan monks and, later to a hospital 1147.

The building was modified in the 11th-12th centuries in a style similar to that of the Duomo, being reconsecrated by Pope Eugene II in 1148.

Since 1409 the building complex was given to the administration of the cardinal Landolfo di Marramauro, then since 1552 was given to the Grifoni family and, after 1565 to the Holy Order of St. Stephen. After his suppression, in 1798 the church become a Parish.

In 1853 the building underwent some significant reconstruction, directed by Pietro Bellini, which aimed to restore its romanesque origins. During the Second World War, this church, like many in Pisa, suffered damage. Restoration efforts were pursued in 1949- 1952. In the course of this work, the buildings in the back were demolished, restoring the small Sant'Agata chapel to its original free-standing state.

The exterior has bichrome marble bands which re-use Roman stones. The façade, designed in the 12th century , but completed in 14th maybe by Giovanni Pisano, has two corps with pilaster strips, blind arches, marble intarsias and three orders of loggias in the upper section.

The interior is on the Latin cross plan with a nave and two aisles divided by columns in Elban granite, an apse and a dome on the crossing with the transept. It houses a 13th century Crucifix on panel, frescoes by Buonamico Buffalmacco and a Madonna with Saints by Turino Vanni (14th century), but most of all a 2nd century Roman sarcophagus used as medieval tomb. The relief on this sarcophagus was used as a model by both Nicola Pisano and his pupil Arnolfo di Cambio.

Sant'Agata Chapel

Behind the church is the St. Agatha Chapel, a small Romanesque chapel built around 1063 by the monks. It was connected to the church by edifices which were demolished after World War II.

It is an octagonal structure in brickwork, featuring pilasters, arches including mullioned windows and an unusual pyramidal cusp. The interior houses remains of 12th century wall decorations.

Art in Tuscany | Pisa | Church of San Paolo a Ripa d'Arno

|

|

San Paolo a Ripa d'Arno

Sant'Agata Chapel

|

The Church of San Piero a Grado or Basilica di San Piero Apostolo rises exactly where once was a now disappeared port of the Pisan Republic, where, according to the legend, St. Peter landed in Italy from Antiochia in 44 AD.

Archaeological excavations have shown the presence of a Palaeo-Christian edifice in the area, built over civil Roman structures, which was later replaced by a larger church in the early Middle Ages (8th-9th centuries). The current construction, begun in the 10th century and renovated in the late 11th-early 12th centuries, has a basilica plan with a nave and two aisles. Unusual is the presence of an apses the facade, probably built after the crumbling of the facade due to a flood of the Arno river. The entrance is on the northern side.

The exterior, made of stone of different provenance, is marked by pilaster strips and arches over which are precious ceramic basins (the originals are in the National Museum of St. Matthew in Pisa) of Islamic, Majorca and Sicilian manufacture decorated with geometrical and figurative motifs (10th-11th centuries).

The 12th century bell tower was destroyed in 1944. Only the base has been rebuilt.

The large and solemn interior, with truss ceiling, is divided into a nave and two aisles by antique columns with classical capitals. In the western part is a Gothic ciborium (early 15th century) which marks the place where Peter would pray for the first time.

On the walls of the nave is a large fresco cycle, recently restored, by the Lucchese Deodato Orlandi (early 14th century), which was commissioned by the Caetani family for the 1300 jubilee. In the lower part are Portraits of Popes, from St. Peter to John XVIII (1303); the intermediate portion has thirty panels with Histories of St. Peter's Life (as well of those of St. Paul, Constantine and St. Sylvester), similar to those in the Old St. Peter's Basilica and to Cimabue's work at San Francesco in Assisi. In the upper area are portrayed the Walls of the Heaven City, largely restored in the following centuries.

Art in Tuscany | Pisa | San Piero a Grado or Basilica di San Piero Apostolo

|

|

|

|

Francesco Traini or Buonamico Buffalmacco, Triumph of Death, fresco (detail) Campo Santo, Pisa, 1330s |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Villa Medici in Fiesole, lower garden |

|

Abbey of Sant 'Antimo |

|

Siena, duomo |

| |

|

|

|

|

[1] Francesco Traini was an Italian painter who was demonstrably active from 1321 to approx. 1365 in Pisa and Bologna. He appears to have been a follower of Andrea Orcagna. There is only one work known to be by Traini: in 1345 he signed and dated a polyptych of the Pisan church S. Caterina, showing Saint Dominic and eight hagiographic scenes (now in the Museo Nazionale, Pisa).

Buonamico di [son of] Martino or Buonamico Buffalmacco (active c. 1315–1336) was an Italian painter who worked in Florence, Bologna and Pisa. Although none of his known work has survived, he is widely assumed to be the painter of a most influential fresco cycle in the Camposanto in Pisa, featuring the The Three Dead and the Three Living, the Triumph of Death, the Last Judgement, the Hell, and the Thebais (several episodes from the lives of the Holy Fathers in the Desert). Painted some ten years before the Black Death spread over Europe in 1348, the cycle - a "painted sermon" (L. Bolzoni) - enjoyed an extraordinary success after that date, and was often imitated throughout Italy. The youngsters' party enjoying themselves in a beautiful garden while Death piles mounds of corpses all around is likely to have inspired the setting of Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron, written a few years after the Black Death.

Boccaccio (in his Decameron) and Franco Sacchetti (in his Il trecentonovelle) both describe Buonamico as being a practical joker. Boccaccio features Buonamico along with his friends and fellow painters Calandrino and Bruno in several tales (Day VIII, tales 3, 6, and 9; Day IX, tales 3 and 5). Typically in these stories, Buonamico uses his wits to play tricks on his friends and associates: convincing Calandrino that a stone he possesses (heliotrope) confers invisibility (VIII/3), stealing a pig from Calandrino (VIII, 6), convincing the physician Master Simone of an opportunity to ally himself with the devil (VIII, 9), convincing Calandrino that he has become pregnant (IX, 3), convincing Calandrino that a particular scroll can cause a woman to fall in love with him (IX, 5). Throughout the stories, Buonamico is frequently depicted at work painting in the houses of notable gentlemen in Florence but eager to take time to eat, drink and be merry.

Giorgio Vasari includes a biography of Buonamico in his Lives, in which he tells several anecdotes about his comic escapades.[1] Vasari tells of Buonamico's youthful tricking of his master Tafi during his apprenticeship, various pranks and tricks that Buonamico played on his patrons, and his habit of embedding texts within his paintings. Dismissed by Vasari as just another of the witty painter's gags, which his "clumsy" contemporaries had misunderstood and foolishly imitated, the Camposanto frescoes are actually scattered with texts, a possible indication of the veracity of Vasari's remark. In the scroll over the cripple beggars in the center of The Triumph of Death, for instance, it says, "Since prosperity has completely deserted us, O Death, you who are the medicine for all pain, come to give us our last supper."

Vasari discusses various paintings by the artist which no longer exist, and many of which had already perished by the time of Vasari's writing in the sixteenth century. He describes a series of paintings at the convent of Faenza in Florence (already destroyed by the sixteenth century), works for the abbey of Settimo (now also lost), tempera paintings for the monks of the abbey of Certosa (also in Florence), and frescoes in the Badia at Florence. He describes a series of paintings depicting the life of Saint Catherine of Siena in a chapel in her honor in Assisi at the Basilica of Saint Francis (an attribution rejected by later scholars), and several prominent commissions at various abbeys and convents in Pisa. Interestingly, Vasari does not attribute the famed Pisan frescoes now associated with Buonamico to the painter, but rather, credits him with four frescoes at the Camposanto depicting the beginning of the world through the building of Noah's Ark, which later scholars have instead attributed to Piero di Puccio of Orvieto.

Vasari presents conflicting information regarding Buonamico's death, dating it to the year 1340, but also stating that he was still alive in 1351. In any case, he is said to have died at the age of 78, in poverty, and to have been buried at the hospital of Santa Maria Novella, in Florence.

[2] The Triumph of Death, fig.19 at the Camposanto in Pisa, has been puzzling generations of art historians. From G. Vasari to the twentieth century, the attribution and the date of this grandiose masterwork was very much a matter for debate. In Buffalmacco e il Trionfo della Morte L. Bellosi attributed the famous fresco beyond doubt to Buonamico Buffalmacco. He dates the artwork to about 1336. L. Battaglia Ricci in Ragionare nel Giardino studied the theme in correlation to Boccaccio's Decameron, pointing to the ten personages, seven women and three men, appearing in the gardens of the famous works of both Buffalmacco and Boccaccio. Thus, art historians have changed their view and approach in the understanding of this famous masterpiece appearing in the first half of the fourteenth century in Italy. Many scholars have been tempted to relate the famous Triumph of Death and paintings displaying the Dead and the Death to the Black Death in 1348, which devastated social life in Tuscany and other regions of Europe. When looking at these frescoes representing the Triumph of Death there is no doubt that medieval people felt death to be a drama. The plague may have given reason to personify death in its most dramatic nature, but this was not the case for having personified death in the shape of a woman armed with scythe and in the most vivid expression.

Ingrid Valser, The Theme of Death in Italian Art: The Triumph of Death, Department of Art History McGill University, Montréal, pp 59.

[3] The decoration of the façade is also directed by Vasari. It is composed in three layers; the lower part is decorated with 12 constellation of the year, the middle with allegorical figures like Art and Virtue, and the topmost with the bust of the Medici Dukes, and at the centre, the famous emblem of the Medici family.

Since Napoleon founded the Normal School in 1810 and gave the use of the building to the school, it is still occupied by the Scuola Normale

The words sgraffito and sgraffiti come from the Italian word sgraffiare (”to scratch”), ultimng “to write”.

Graffiti, the bane of all modern cities in the form of spray paint, in its original sense refers to marks scratched onto a surface with a tapered point. The graffito technique has been used since prehistoric times. Decades ago, my father showed me graffito animals, birds and people carved on the tufa cave walls in northern New Mexico. But in Florence, starting in the 1400s, it was a technique of wall design, where the top layer of pigment or colored plaster is scratched through to reveal an underlying layer.

The historian and artist Giorgio Vasari recorded the graffito technique step by step. First, one paints the wall of a palazzo with a layer of lime plaster, coloured with burnt herbs or other dark pigments. Once the first layer is dry, another is painted on, this time of white plaster, distributed uniformly. On top of this second layer are laid punched-out designs, or stencils, which are reproduced on the wall with powdered charcoal (referred to as tecnica dello spolvero in Italian). A tapered awl is then used to trace the resulting pattern on the wall, cutting through the layer of white plaster to reveal the darker, underlying layer. Thus, by using the same colours as a palazzo’s frescos, the graffito designs could be used to add shadow and depth to the overall decoration.

|

[4] Over the centuries, the Camposanto became the cultural center of Pisa and the region. Many were buried there, and priceless Roman sarcophagi and statues, along with biblical relics, were housed there. The walls were completely decorated in immaculate frescos, and were beautiful beyond description. In short, the Camposanto was the one of the most important and priceless historical structures in all of Italy. The painting seen here shows how it looked.

On July 27, 1944, a wayward Allied bombs started a fire nearby that quickly spread to the Camposanto. The wooden rafters burst into flame and melted the lead on the roof, which dripped down and completely destroyed everything inside.

After World War II, restoration work began. The roof was restored as closely as possible to its pre-war appearance and the frescoes were separated from the walls to be restored and displayed elsewhere. Once the frescoes had been removed, the preliminary drawings, called sinopie were also removed. These under-drawings were separated using the same technique used on the frescoes and now they are in the Museum of the Sinopie, on the opposite side of the Square. The restored frescoes that still exist are gradually being transferred to their original locations in the cemetery, inside the cemetery, to restore the Campo Santo's pre-war appearance. |

|

Leo von Klenze, The Camposanto in Pisa, 1858, New Pinacothek of Munich

|

| |

|

|

|

Pisa, Camposanto Monumentale, after 27 July 1944 |

Art in Tuscany | Tuscan art cities | Pisa, Camposanto Monumentale

Pisa | San Piero a Grado or Basilica di San Piero Apostolo

Art in Tuscany | Pisa | Church of San Paolo a Ripa d'Arno

Official website | www.opapisa.it

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden |

|

Florence, Duomo |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Villa I Tatti |

|

Spoleto

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Pisa | History

|

Ancient times

Pisa's origins remained unknown for centuries. The city lies at the junction of two rivers, the Arno and the Serchio in the Ligurian Sea forming a laguna area. The Pelasgi, the Greeks, the Etruscans and the Ligurians have variously been proposed as founders of the city. Archeological remains from the 5th century BC confirmed the existence of a city at the sea, trading with Greeks and Gauls. The presence of an Etruscan necropolis, discovered during excavations in the Arena Garibaldi in 1991, allowed to clarify its Etruscan origins.

Ancient Roman authors referred to Pisa as an old city. Servius wrote that the Teuti, or Pelopes, the king of the Pisei, founded the town thirteen centuries before the start of the common era. Strabo referred Pisa's origins to the mythical Nestor, king of Pylos, after the fall of Troy. Virgil in his Aeneid states that Pisa was already a great and developed centre by the times described; the foundation of the city in the 'Etruscan lands' has been credited to settlers from the Alpheus coast. The maritime role of Pisa should have been already prominent if the ancient authorities ascribed to it the invention of the rostrum: it took advantage of being the only port along the western coast from Genoa (then a small village) to Ostia. Pisa served as a base for Roman naval expeditions against Ligurians, Gauls and Carthaginians. In 180 BC, it became a Roman colony under Roman law, as Portus Pisanus. In 89 BC, Portus Pisanus became a municipium. Emperor Augustus fortified the colony into an important port and changed the name in Colonia Iulia obsequens. From 313 it became the seat of a bishopric.

Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages

During the later years of the Roman Empire, Pisa did not decline as much as the other cities of Italy, probably thanks to the complexity of its river system and its consequent ease of defence. In the 7th century Pisa helped Pope Gregory I by supplying numerous ships in his military expedition against the Byzantines of Ravenna: Pisa was the sole Byzantine centre of Tuscia to fall peacefully in Lombard hands, through assimilation with the neighbouring region where their trading interests were prevailing. Pisa began in this way its rise to the role of main port of the Upper Tyrrhenian Sea and became the main trading centre between Tuscany and Corsica, Sardinia and the southern coasts of France and Spain.

After Charlemagne had defeated the Lombards under the command of Desiderius in 774, Pisa went through a crisis but soon recovered. Politically it became part of the duchy of Lucca. In 930 Pisa became the county centre (status it maintained until the arrival of Otto I) within the mark of Tuscia. Lucca was the capital but Pisa was the most important city, as in the middle of 10th century Liutprand of Cremona, bishop of Cremona, called Pisa Tusciae provinciae caput ("capital of the province of Tuscia"), and one century later the marquis of Tuscia was commonly referred to as "marquis of Pisa". In 1003 Pisa was the protagonist of the first communal war in Italy, against Lucca of course. From the naval point of view, since the 9th century the emergence of the Saracen pirates urged the city to expand its fleet: in the following years this fleet gave the town an opportunity for more expansion. In 828 Pisan ships assaulted the coast of North Africa. In 871 they took part in the defence of Salerno from the Saracens. In 970 they gave also strong support to the Otto I's expedition, defeating a Byzantine fleet in front of Calabrese coasts.

11th century

The power of Pisa as a mighty maritime nation began to grow and reached its apex in the 11th century when it acquired traditional fame as one of the four main historical Maritime Republics of Italy (Repubbliche Marinare).

At that time, the city was a very important commercial centre and controlled a significant Mediterranean merchant fleet and navy. It expanded its powers by the sack in 1005 of Reggio Calabria in the south of Italy. Pisa was in continuous conflict with the Saracens, who had their bases in Corsica, for control of the Mediterranean. In 1017 Sardinian Giudicati were military supported by Pisa, in alliance with Genoa, to defeat the Saracen king Mugahid that settled a logistic base on the north of Sardinia the year before. This victory gave Pisa the supremacy in the Tyrrhenian Sea. When the Pisans subsequently ousted the Genoese from Sardinia, a new conflict and rivalry was born between these mighty marine republics. Between 1030 and 1035, Pisa went on to successfully defeat several rival towns in Sicily and conquer Carthage in North Africa. In 1051–1052 the admiral Jacopo Ciurini conquered Corsica, provoking more resentment from the Genoese. In 1063 admiral Giovanni Orlando, coming to the aid of the Norman Roger I, took Palermo from the Saracen pirates. The gold treasure taken from the Saracens in Palermo allowed the Pisans to start the building of their cathedral and the other monuments which constitute the famous Piazza del Duomo.

In 1060 Pisa had to engage in their first battle with Genoa. The Pisan victory helped to consolidate its position in the Mediterranean. Pope Gregory VII recognised in 1077 the new "Laws and customs of the sea" instituted by the Pisans, and emperor Henry IV granted them the right to name their own consuls, advised by a Council of Elders. This was simply a confirmation of the present situation, because in those years the marquis had already been excluded from power. In 1092 Pope Urban II awarded Pisa the supremacy over Corsica and Sardinia, and at the same time raising the town to the rank of archbishopric.

Pisa sacked the Tunisian city of Mahdia in 1088. Four years later Pisan and Genoese ships helped Alfonso VI of Castilla to push El Cid out of Valencia. A Pisan fleet of 120 ships also took part in the First Crusade and the Pisans were instrumental in the taking of Jerusalem in 1099. On their way to the Holy Land the ships did not miss the occasion to sack some Byzantine islands: the Pisan crusaders were led by their archbishop Daibert, the future patriarch of Jerusalem. Pisa and the other Repubbliche Marinare took advantage of the crusade to establish trading posts and colonies in the Eastern coastal cities of the Levant. In particular the Pisans founded colonies in Antiochia, Acre, Jaffa, Tripoli, Tyre, Joppa, Latakia and Accone. They also had other possessions in Jerusalem and Caesarea, plus smaller colonies (with lesser autonomy) in Cairo, Alexandria and of course Constantinople, where the Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus granted them special mooring and trading rights. In all these cities the Pisans were granted privileges and immunity from taxation, but had to contribute to the defence in case of attack. In the 12th century the Pisan quarter in the Eastern part of Constantinople had grown to 1,000 people. For some years of that century Pisa was the most prominent merchant and military ally of the Byzantine Empire, overcoming Venice itself.

12th century

In 1113 Pisa and the Pope Paschal II set up, together with the count of Barcelona and other contingents from Provence and Italy (Genoese excluded), a war to free the Balearic Islands from the Moors: the queen and the king of Majorca were brought in chains to Tuscany. Even though the Almoravides soon reconquered the island, the booty taken helped the Pisans in their magnificent programme of buildings, especially the cathedral and Pisa gained a role of pre-eminence in the Western Mediterranean.

In the following years the mighty Pisan fleet, led by archbishop Pietro Moriconi, drove away the Saracens after ferocious combats. Though short-lived, this success of Pisa in Spain increased the rivalry with Genoa. Pisa's trade with the Languedoc and Provence (Noli, Savona, Fréjus and Montpellier) were an obstacle to the Genoese interests in cities like Hyères, Fos, Antibes and Marseille.

The war began in 1119 when the Genoese attacked several galleys on their way to the motherland, and lasted until 1133. The two cities fought each other on land and at sea, but hostilities were limited to raids and pirate-like assaults.

In June 1135, Bernard of Clairvaux took a leading part in the Council of Pisa, asserting the claims of pope Innocent II against those of pope Anacletus II, who had been elected pope in 1130 with Norman support but was not recognised outside Rome. Innocent II resolved the conflict with Genoa, establishing the sphere of influence of Pisa and Genoa. Pisa could then, unhindered by Genoa, participate in the conflict of Innocent II against king Roger II of Sicily. Amalfi, one of the Maritime Republics (though already declining under Norman rule), was conquered on 6 August 1136: the Pisans destroyed the ships in the port, assaulted the castles in the surrounding areas and drove back an army sent by Roger from Aversa. This victory brought Pisa to the peak of its power and to a standing equal to Venice. Two years later its soldiers sacked Salerno.

In the following years Pisa was one of the staunchest supporters of the Ghibelline party. This was much appreciated by Frederick I. He issued in 1162 and 1165 two important documents, with the following grants: apart from the jurisdiction over the Pisan countryside, the Pisans were granted freedom of trade in the whole Empire, the coast from Civitavecchia to Portovenere, a half of Palermo, Messina, Salerno and Naples, the whole of Gaeta, Mazara and Trapani, and a street with houses for its merchants in every city of the Kingdom of Sicily. Some of these grants were later confirmed by Henry VI, Otto IV and Frederick II. They marked the apex of Pisa's power, but also spurred the resentment of cities like Lucca, Massa, Volterra and Florence, who saw their aim to expand towards the sea thwarted. The clash with Lucca also concerned the possession of the castle of Montignoso and mainly the control of the Via Francigena, the main trade route between Rome and France. Last but not least, such a sudden and large increase of power by Pisa could only lead to another war with Genoa.

Genoa had acquired a largely dominant position in the markets of Southern France. The war began presumably in 1165 on the Rhône, when an attack on a convoy, directed to some Pisan trade centres on the river, by the Genoese and their ally, the count of Toulouse failed. Pisa on the other hand was allied to Provence. The war continued until 1175 without significant victories. Another point of attrition was Sicily, where both the cities had privileges granted by Henry VI. In 1192, Pisa managed to conquer Messina. This episode was followed by a series of battles culminating in the Genoese conquest of Syracuse in 1204. Later, the trading posts in Sicily were lost when the new Pope Innocent III, though removing the excommunication cast over Pisa by his predecessor Celestine III, allied himself with the Guelph League of Tuscany, led by Florence. Soon he stipulated a pact with Genoa too, further weakening the Pisan presence in Southern Italy.

To counter the Genoese predominance in the southern Tyrrhenian Sea, Pisa strengthened its relationship with their Spanish and French traditional bases (Marseille, Narbonne, Barcelona, etc.) and tried to defy the Venetian rule of the Adriatic Sea. In 1180 the two cities agreed to a non-aggression treaty in the Tyrrhenian and the Adriatic, but the death of Emperor Manuel Comnenus in Constantinople changed the situation. Soon there were attacks on Venetian convoys. Pisa signed trade and political pacts with Ancona, Pula, Zara, Split and Brindisi: in 1195 a Pisan fleet reached Pola to defend its independence from Venice, but the Serenissima managed soon to reconquer the rebel sea town.

One year later the two cities signed a peace treaty which resulted in favourable conditions for Pisa. But in 1199 the Pisans violated it by blockading the port of Brindisi in Puglia. In the following naval battle they were defeated by the Venetians. The war that followed ended in 1206 with a treaty in which Pisa gave up all its hopes to expand in the Adriatic, though it maintained the trading posts it had established in the area. From that point on the two cities were united against the rising power of Genoa and sometimes collaborated to increase the trading benefits in Constantinople.

13th century

In 1209 there were in Lerici two councils for a final resolution of the rivalry with Genoa. A twenty-year peace treaty was signed. But when in 1220 the emperor Frederick II confirmed his supremacy over the Tyrrhenian coast from Civitavecchia to Portovenere, the Genoese and Tuscan resentment against Pisa grew again. In the following years Pisa clashed with Lucca in Garfagnana and was defeated by the Florentines at Castel del Bosco. The strong Ghibelline position of Pisa brought this town diametrically against the Pope, who was in a strong dispute with the Empire. And indeed the pope tried to deprive the town of its dominions in northern Sardinia.

In 1238 Pope Gregory IX formed an alliance between Genoa and Venice against the empire, and consequently against Pisa too. One year later he excommunicated Frederick II and called for an anti-Empire council to be held in Rome in 1241. On 3 May 1241, a combined fleet of Pisan and Sicilian ships, led by the Emperor's son Enzo, attacked a Genoese convoy carrying prelates from Northern Italy and France, next to the Isola del Giglio, in front of Tuscany: the Genoese lost 25 ships, while about thousand sailors, two cardinals and one bishop were taken prisoner. After this outstanding victory the council in Rome failed, but Pisa was excommunicated. This extreme measure was only removed in 1257. Anyway, the Tuscan city tried to take advantage of the favourable situation to conquer the Corsican city of Aleria and even lay siege to Genoa itself in 1243.

The Ligurian republic of Genoa, however, recovered fast from this blow and won back Lerici, conquered by the Pisans some years earlier, in 1256.

The great expansion in the Mediterranean and the prominence of the merchant class urged a modification in the city's institutes. The system with consuls was abandoned and in 1230 the new city rulers named a Capitano del Popolo ("People's Chieftain") as civil and military leader. In spite of these reforms, the conquered lands and the city itself were harassed by the rivalry between the two families of Della Gherardesca and Visconti. In 1237 the archbishop and the Emperor Frederick II intervened to reconcile the two rivals, but the strains did not cease. In 1254 the people rebelled and imposed twelve Anziani del Popolo ("People's Elders") as their political representatives in the Commune. They also supplemented the legislative councils, formed of noblemen, with new People's Councils, composed by the main guilds and by the chiefs of the People's Companies. These had the power to ratify the laws of the Major General Council and the Senate.

Decline

The decline began on 6 August 1284, when the numerically superior fleet of Pisa, under the command of Albertino Morosini, was defeated by the brilliant tactics of the Genoese fleet, under the command of Benedetto Zaccaria and Oberto Doria, in the dramatic naval Battle of Meloria. This defeat ended the maritime power of Pisa and the town never fully recovered: in 1290 the Genoese destroyed forever the Porto Pisano (Pisa's Port), and covered with salt. The region around Pisa did not permit the city to recover from the loss of thousands of sailors from the Meloria, while Liguria guaranteed enough sailors to Genoa. Goods continued to be traded, albeit in reduced quantity, but the end came when the River Arno started to change course, preventing the galleys from reaching the city's port up the river. It seems also that nearby area became infested with malaria. Within 1324 also Sardinia was entirely lost in favour of the Aragonese.

Always Ghibelline, Pisa tried to build up its power in the course of the 14th century and even managed to defeat Florence in the Battle of Montecatini (1315), under the command of Uguccione della Faggiuola. Eventually, however, divided by internal struggles and weakened by the loss of its mercantile strength, Pisa was conquered by Florence in 1406. In 1409 Pisa was the seat of a council trying to set the question of the Great Schism. Furthermore in the 15th century, access to the sea became more and more difficult, as the port was silting up and was cut off from the sea. When in 1494 Charles VIII of France invaded the Italian states to claim the Kingdom of Naples, Pisa grabbed the opportunity to reclaim its independence as the Second Pisan Republic.

But the new freedom did not last long. After fifteen years of battles and sieges, Pisa was reconquered in 1509 by the Florentine troops led by Antonio da Filicaja, Averardo Salviati and Niccolò Capponi. Its role of major port of Tuscany went to Livorno. Pisa acquired a mainly, though secondary, cultural role spurred by the presence of the University of Pisa, created in 1343. Its decline is clearly shown by its population, which has remained almost constant since the Middle Ages.

Pisa was the birthplace of the important early physicist, Galileo Galilei. It's still the seat of an archbishopric; it has become a light industrial centre and a railway hub. It suffered repeated destruction during World War II. |

| |

| |

This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Francesco Traini, Buonamico Buffalmacco, Santa Maria della Spina, Palazzo della Carovana, Piazza dei Miracoli and Pisa, published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pisa.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()