| |

|

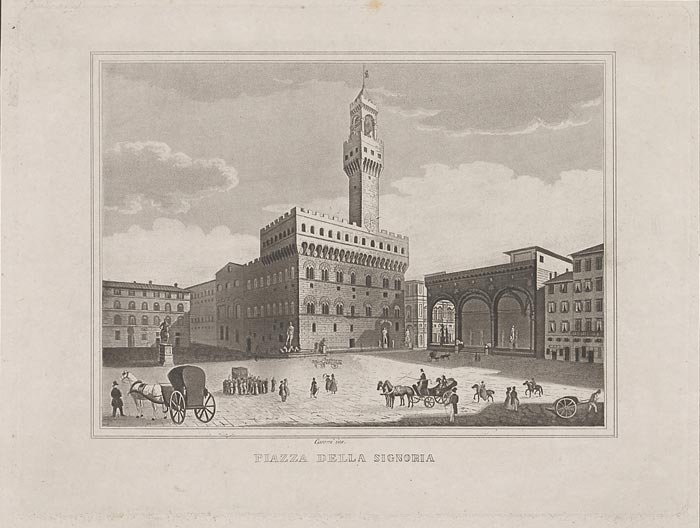

The Loggia dei Lanzi, also called the Loggia della Signoria, is a building on a corner of the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, Italy, adjoining the Uffizi Gallery. It consists of wide arches open to the street, three bays wide and one bay deep. The arches rest on clustered pilasters with Corinthian capitals. The wide arches appealed so much to the Florentines, that Michelangelo even proposed that they should be continued all around the Piazza della Signoria.

Sometimes erroneously referred to as Loggia dell' Orcagna [1] because it was once thought to be designed by that artist, it was built between 1376 and 1382 by Benci di Cione and Simone di Francesco Talenti, [2] possibly following a design by Jacopo di Sione, to house the assemblies of the people and hold public ceremonies, [1] such as the swearing into office of the Gonfaloniers and the Priors. Simone Talenti is also well-known from his contributions to the churches Orsanmichele and San Carlo.

The vivacious construction of the Loggia is in stark contrast with the severe architecture of the Palazzo Vecchio. It is effectively an open-air sculpture gallery of antique and Renaissance art.

The name Loggia dei Lanzi dates back to the reign of Grand Duke Cosimo I, when it was used to house his formidable landsknechts (In Italian: "Lanzichenecchi", corrupted to Lanzi), or German mercenary pikemen. [1] After the construction of the Uffizi at the rear of the Loggia, the Loggia's roof was modified by Bernardo Buontalenti and became a terrace from which the Medici princes could watch ceremonies in the piazza.

|

|

| |

Architectural setting

|

|

|

On the façade of the Loggia, below the parapet, are trefoils with allegorical figures of the four cardinal virtues (Fortitude, Temperance, Justice and Prudence) by Agnolo Gaddi. [3] Their blue enamelled background is the work of Leonardo, a monk, while the golden stars were painted by Lorenzo de' Bicci. The vault, composed of semicircles, was done by the Florentine Antonio de' Pucci. On the steps of the Loggia are the Medici lions; two Marzoccos, marble statues of lions, heraldic symbols of Florence; that on the right is from Roman times and the one on the left was sculpted by Flaminio Vacca in 1598. It was originally placed in the Villa Medici in Rome, but found its final place in the Loggia in 1789.

On the side of the Loggia, there is a Latin inscription from 1750 commemorating the change of the Florentine calendar in 1749 to bring it into line with the Roman calendar. The Florentine calendar began on 25 March instead of 1 January. Other inscription from 1893 records the Florentines who distinguished themselves during the annexation of Milan (1865), Venice (1866) and Rome (1871) to the kingdom of Italy.

|

|

An image of Justice, one of the four cardinal virtues Her sword and her hand holding scales have broken away [9]

|

|

|

Underneath the bay on the far left is the bronze statue of Perseus by Benvenuto Cellini. [4] Perseus with the head of Medusa, also known as Cellini’s Persus, is a bronze sculpture. It is considered a masterpiece of Italian Mannerism, and is one of the most famous statues in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria. The statue depicts Perseus as he stands on Medusa’s body and holds her head up in the air. In the scene, he has just beheaded her with his sword, and triumphantly lifts up her head, holding it by her hair. The statute has a rather high pedestal, adorned with small bronzes that are now at the Bargello museum, so that the spectator must look up at it as Perseus looks down toward the ground. The refined pedestal bronzes are an example of Cellini’s unparalleled talent when working on smaller pieces. This was due to the fact that he was also an expert goldsmith.

The statute was commissioned by Cosimo I dei Medici, after he had just been named Grand Duke, and was completed from 1545 to 1554. The original still stands in the Loggia today.

The richly decorated marble pedestal, also by Cellini, shows four graceful bronze statuettes of Jupiter, Mercurius, Minerva and Danaë. The bas-relief on the pedestal, representing Perseus freeing Andromeda, is a copy of the one in Bargello.

Benvenuto Cellini worked almost ten years on this bronze (1545-1554). His wax design was immediately approved by Cosimo I de' Medici. He met numerous difficulties which, according to his autobiography, almost brought him to the brink of death. The casting of this bronze statue was several times unsuccessful. When attempting again, the melting furnace got overheated, spoiling the casting of the bronze. Cellini gave orders to feed the furnace with his household furniture and finally with about 200 pewter dishes and plates, and his pots and pans. This caused the bronze to flow again. After the bronze had cooled, the statue was miraculously finished, except for three toes on the right foot. These were added later.

|

|

The statue of Perseus by Cellini depicts a decapitation that was intended as a warning to enemies of Cosimo I

|

|

One of the lions under the Loggia dei Lanzi, and Michelangelo's David, Piazza della Signoria in Florence [10]

On the steps of the Loggia are the Medici lions; two Marzoccos, marble statues of lions, heraldic symbols of Florence; the one above was sculpted by Flaminio Vacca in 1598

|

| On the far right is the manneristic group Rape of the Sabine Women by the Flemish artist Jean de Boulogne, better known by his Italianized name Giambologna. [5] This impressive work was made from one imperfect block of white marble, the largest block ever transported to Florence. The goccia model is now in the Galleria dell' Academia. [6] Giambologna wanted to create a composition with the figura serpentina, an upward snakelike spiral movement to be examined from all sides. This is the first group representing more than a single figure in European sculptural history to be conceived without a dominant viewpoint. It can be equally admired from all sides. The marble pedestal, also by Giambologna, represents bronze bas-reliefs with the same theme. This marble and bronze group is in the Loggia since 1583.

Nearby is Giambologna's less celebrated marble sculpture Hercules beating the Centaur Nessus (1599) and placed here in 1841 from the Canto de' Carnesecchi. It was sculpted from one solid block of white marble with the help of Pietro Francavilla

The group Menelaus supporting the body of Patroclus, discovered in Rome stood originally at the southern end of the Ponte Vecchio. There is another version of this much-restored Roman marble in the Palazzo Pitti. It is an ancient Roman sculpture from the Flavian era, copied from a Hellenistic Pergamene original of the mid third century BC. This marble group was discovered in Rome. It has undergone restorations by Ludovico Salvetti, to a model by Pietro Tacca (1640) and by Stefano Ricci (about 1830).

The group The Rape of Polyxena, is a fine diagonal sculpture by Pio Fedi from 1865.

|

|

Giambologna, The Rape of the Sabine Women (detail)

Menelaus supporting the body of Patroclus, a much-restored Roman sculpture Menelaus supporting the body of Patroclus, a much-restored Roman sculpture

|

The Loggia della Signoria also houses the Hercules Fighting the Centaur Nessus, commissioned to Giambologna by Grand Duke Ferdinand I around 1594.

Compared to the Rape of the Sabine Women, this group is constructed from a less dynamic stance.

The front viewpoint conditions the onlooker; in fact, only from this view is it possible to appreciate the contrast between Hercules' face and the wild, savage face of the centaur, Nessus; the movement of the hero's body is contrasted by the emphatic movement of the monster's trunk, which bends back diagonally. In actual fact, the group was originally designed to be placed on a pedestal at the crossroads in Canto dei Carnesecchi and it was placed under the Loggia in the mid-19th century.

The reference that the sculptor wished to surpass was that of sculpting something similar to the famous sketch (now in Berlin) of Hercules and Cacus by Baccio Bandinelli: a project conceived around an epic fight, where the semigod holds down his enemy, who has been struck down, but who continues to struggle. The overly emphatic gestures for the weights and volumes that needed to be created using a colossal block of stone led to a second solution by Bandinelli, which now stands in Piazza Signoria. Giambologna started from Bandinelli's revolutionary sketch, which could be seen in the collection of the Grand Dukes in Palazzo Vecchio, rendering it more malleable through a better design, based on a calculated movement of the limbs away from the centre of gravity.

|

|

Giambologna, Hercules Fighting the Centaur Nessus, Loggia dei Lanzi

|

|

Giambologna, Hercules Fighting the Centaur Nessus (detail), Loggia dei Lanzi

|

| On the back of the Loggia are five marble female statues (three are identified as Matidia, Marciana and Agrippina Minor), [7] Sabines and a statue of a barbarian prisoner Thusnelda from Roman times from the era of Trajan to Hadrian. They were discovered in Rome in 1541. The statues had been in the Medici villa at Rome since 1584 and were brought here by Pietro Leopoldo in 1789. They all have significant, modern restorations.

The Feldherrnhalle in Munich, the site of a failed coup by the fledgling Nazi party in 1923, was modelled after the Loggia dei Lanzi. |

|

|

|

| |

|

Art in Tuscany | Churches in Firenze | The Basilica della Santissima Annunziata

The Basilica della Santissima Annunziata (Basilica of the Most Holy Annunciation) is a Roman Catholic minor basilica in Florence and the mother church of the Servite order. It is located at the northeastern side of the Piazza Santissima Annunziata.

It is the principal Marian shrine in Florence.

The principal feast day is March 25th which was also the date of the Florentine New Year for many centuries. The Florentine capodanno was and is celebrated in this Church.

The church stands on the pre-existent oratory of the Servi di Maria (1235). The oratory was built around the miraculous image of Our Lady of the Annunciation by seven young noblemen who decided to take monastic vows and give up worldly pleasures.

Michelozzo built the First Cloister in the mid 15th century. The main body of the Church, started in 1440 by Michelozzo and Pagno Portigiani, was later altered by Alberti, who created the impressive Tribune.

The atrium or portico of the church faces the piazza, and is composed of seven arches, raised on slender Corinthian columns. The central arch was erected by Pope Leo X., after a design by Antonio di San Gallo, and in 1512 it was decorated with a fresco representing Faith, Hope, and Charity, by Jacopo Carucci da Pontormo (1493-1588); but of which unfortunately little now remains.

There are three doors under the portico; that to the left opens on the cloister and leads to the convent. To the right is the entrance to the Chapel of the Pucci family, dedicated to San Sebastiano. The central door under the portico opens on the cortile, or entrance court.

The Church of the SS. Annunziata itself is composed of a single nave, with five chapels on either side, two short transepts, and a circular choir, surmounted by a cupola. The whole is richly decorated with paintings, stucco, and gilding. The interior is excessively baroque. If you are fond of the Baroque, you`ll swoon. It is a surfeit of the Baroque.

Walking in Tuscany | Florence | Walking in the Bargello Neighbourhood

[0] To this day, the squares characterize the appearance of Florence. From a historical perspective, their development was linked to various factors. Thus the Piazza and Palazzo della Signoria became a centre of political authority to counterbalance the ecclesiastic power at the cathedral. Smaller squares emerged in front of the main churches and at road junctions. The large forecourts of the converts that settled outside the second city wall brought a new type of square along during the formidable rise of the mendicant orders in the 13th century – they all formed spaces of religious, social, economic and cultural life from this point on. During the Renaissance, the targeted structuring of urban space became a central focus of architecture: The most famous example of this is the Piazza della Santissima Annunziata with Brunelleschi’s portico. This and other Florentine squares were common motifs in print reproductions. In character, some of the views shown here go back to the series of etchings from Giuseppe Zocchi’s “Scelta di XXIV Vedute”, which appeared in 1744 and enjoyed huge success. One example of this is the (nevertheless laterally transposed) reproduction of San Pier Maggiore, which represents an important historical document at the same time: In 1783, the church was demolished with the exception of the three arches of the portico; the Via San Pier Maggiore today runs through the former nave.

Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz | Squares

Address: Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, Via Giuseppe Giusti 44, 50121 Firenze

[1] a b c Zucconi, Guido (1995). Florence: An Architectural Guide. San Giovanni Lupatoto, Vr, Italy: Arsenale Editrice srl. ISBN 88-7743-147-4.

[2] loggia. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

[3] Gaddi, Agnolo. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

[4] Florence. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

'Perseus with the head of Medusa, also known as Cellini’s Persus, is a bronze sculpture. It is considered a masterpiece of Italian Mannerism, and is one of the most famous statues in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria. Located in the Loggia dei Lanzi, it depicts Perseus as he stands on Medusa’s body and holds her head up in the air. In the scene, he has just beheaded her with his sword, and triumphantly lifts up her head, holding it by her hair. The statute has a rather high pedestal, adorned with small bronzes that are now at the Bargello museum, so that the spectator must look up at it as Perseus looks down toward the ground. The refined pedestal bronzes are an example of Cellini’s unparalleled talent when working on smaller pieces. This was due to the fact that he was also an expert goldsmith.

The statute was commissioned by Cosimo I dei Medici, after he had just been named Grand Duke, and was completed from 1545 to 1554. The original still stands in the Loggia today. It has stood there since its completion in 1554, except for a period of restoration that ended in 1998. Cellini’s Perseus recalls Donatello’s bronze sculpture Judith and Holofernes (1460), but Cellini takes a step away from the early Renaissance style towards the characteristic titanism of the Italian Mannerism. Cellini’s Perseus also has political meaning, just like the vast majority of the statuary in the piazza. Indeed, it represents the new Grand Duke’s desire to break away from experiences of the earlier republic and send a message to the people, which are represented by Medusa. Serpents emerge from Medusa’s body, representing the people’s many past conflicts that had only worked to threatened and obstruct true democracy. Making the statue proved extremely difficult for Cellini, who truly put his talents to the test. He often spoke of his difficulty with Perseus in his autobiography. He complained about the difficulty fusing the statue in his kiln, and how he used all of the dishware in his home to make it. Fun fact: It is believed that Cellini used a young lover as his model for the statute, and on the back of Perseus’ neck, there is the small portrait of a bearded man, which many maintain is Cellini himself. Florentine singer-songwriter Riccardo Marasco sings about this statue in a song called “L’alluvione” from his album "Il porcellino".' [Se also www.turismo.intoscana.it]

[5] Giambologna. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

Giambologna was born in Douai, Flanders (now in France). After youthful studies in Antwerp with the architect-sculptor Jacques du Broeucq,[1] he moved to Italy in 1550, and studied in Rome. Giambologna made detailed study of the sculpture of classical antiquity. He was also much influenced by Michelangelo, but developed his own Mannerist style, with perhaps less emphasis on emotion and more emphasis on refined surfaces, cool elegance and beauty.

[6] Copy of the rape of the Sabine Woman

The Rape of the Sabine Women is an episode in the legendary history of Rome in which the first generation of Roman men acquired wives for themselves from the neighboring Sabine families. The English word "rape" is a conventional translation of Latin raptio, which in this context means "abduction" rather than its prevalent modern meaning of sexual violation. Recounted by Livy and Plutarch (Parallel Lives II, 15 and 19), it provided a subject for Renaissance and post-Renaissance works of art that combined a suitably inspiring example of the hardihood and courage of ancient Romans with the opportunity to depict multiple figures, including heroically semi-nude figures, in intensely passionate struggle.

The Rape is supposed to have occurred in the early history of Rome, shortly after its founding by Romulus and his mostly male followers. Seeking wives in order to found families, the Romans negotiated unsuccessfully with the Sabines, who populated the area. Fearing the emergence of a rival society, the Sabines refused to allow their women to marry the Romans. Consequently, the Romans planned to abduct Sabine women. Romulus devised a festival of Neptune Equester and proclaimed the festival among Rome's neighbours. According to Livy, many people from Rome's neighbours attended, including folk from the Caeninenses, Crustumini, and Antemnates, and many of the Sabines. At the festival Romulus gave a signal, at which the Romans grabbed the Sabine women and fought off the Sabine men. The indignant abductees were soon implored by Romulus to accept Roman husbands.

Livy is clear that no sexual assault took place. On the contrary, Romulus offered them free choice and promised civic and property rights to women. According to Livy, Romulus spoke to them each in person, "and pointed out to them that it was all owing to the pride of their parents in denying the right of intermarriage to their neighbours. They would live in honourable wedlock, and share all their property and civil rights, and—dearest of all to human nature—would be the mothers of free men."[Livy: The Rape of the Sabines]

[7] Giovanna Giusti Galardi, The Statues of the Loggia Della Signoria in Florence

[8] Source: Il Giambologna a Firenze | www.giambologna.comune.fi.it

[9] Photograph by Thermos, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license

[10] Flaminio Vacca or Vacchi (Caravaggio or Rome, 1538 – Rome, 1605) was an Italian sculptor. His self-portrait (1599) is conserved in the Protomoteca Capitolina on the Campidoglio. At the Villa Medici the two marble Medici lions flank the staircase; one is Roman, its pendant, made to match it in 1600, was by Flaminio Vacca. Vacca's copy was replaced by a copy when Villa Medici was sold by the Grand Duke of Tuscany and moved the lions to Piazza della Signoria, Florence, where with its ancient companion it flanks the steps to the Loggia dei Lanzi. Photograph by McLillo, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license

|

The hidden secrets of southern Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

Podere Santa Pia overlooks the beautiful Tuscan valley where the vineyards thrive and with a view of the chestnut wood on the near hillsides. The view from the main terrace is definitely spectacular. Although this is off the beaten track it is the ideal choice for those seeking a peaceful, uncontaminated environment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The Pucci family

|

|

|

The Pucci family was a major political family in Florence.

The family surname derives from an ancestor named Jacopo, abbreviated to Jacopuccio, then to Puccio, who was considered wise and frequently called upon to settle disputes - there are records of two such interventions in 1264 and 1287. Their former surname seems to have been Saracini, which explains the presence of a maure or moor's head on their crest and coat of arms.

The first Pucci family members to be mentioned date to the 13th century with their subscribing to the Arte dei Legnaioli. These early members include Antonio Pucci, who worked as an architect on the construction of the Loggia della Signoria. His son Puccio Pucci was a merchant who became rich thanks to trade and financial activities in medieval Florence. The first Pucci residences were in the Santa Croce district of Florence, before they moved to that of the church of San Michele Visdomini. They were Guelphs and so they were expelled and their houses demolished after the battle of Montaperti in 1260, though they were soon able to return upon the Ghibellines' explusion from the city. With wealth came political offices such as magistracies, priors and gonfalonieres - the Pucci family produced a total of 23 priors 8 holders of the post of confaloniere di giustizia.

Constant allies of the Medici during the Renaissance, the Pucci were among the families Cosimo de'Medici called upon as a means of indirectly pursuing his own political interests - trusted Medici allies from the Pucci family included Puccio Pucci, who provided Cosimo with money to improve his living conditions in prison whilst Cosimo was imprisoned prior to being exiled. In the early 16th century the Pucci family's prestige rose yet higher, with it producing three cardinals (Roberto, Lorenzo and Antonio Pucci) within a few decades of each other and continuing to be trusted figures in the Medici's ducal and then grand-ducal courts.

However, a momentary bitter break with the Medici came in 1559 when Pandolfo Pucci was ousted from the court of Cosimo I for various slanderous accusations of immorality or (according to other sources) for dreaming of restoring the ancient Republic of Florence. Thus, for revenge or ideological reasons, he conspired against Cosimo with the support of other noble Florentine families, intending to fire an arquebus at Cosimo as he and his retinue walked along the corner of Palazzo Pucci and Via de' Servi to get to the basilica della Santissima Annunziata. The plan had already been shelved, but the Medici intelligence network got wind of it, Pandolfo was hung from a window of the Bargello and the Pucci's properties were seized. As a memorial to the quashing of the plot, or perhaps out of prudence or superstition, it was decided to brick up the window at the corner where the attack was to have occurred, as can still be seen. The Pucci later made peace with the Medici and Niccolò Pucci regained the Palazzo Pucci and its furnishings.

In 1662 Orazio Roberto Pucci acquired the fiefdom of Barsento (Bari) for 4,000 scudi and obtained the title of Marchese di Barsento, the noble title which has since been handed down through the family. The most recent notable family member has been Emilio Pucci, founder of the eponymous post-war fashion house, who became famous (above all in the 1960s and 70s) for more and more fancy but still refined designs. He designed the traditional uniform of the Italian Vigili Urbani with large white gloves and oval beret. His brother Puccio Pucci was also notable, as a sports official for CONI and other organisations. In the 1960s the two brothers split the Palazzo Pucci between them, with Emilio taking the left hand half as the main base for his fashion house and Puccio rebuilding the interior of the central part as a commercial gallery with small craft shops, as it still is today.

Patronage

|

|

The Pucci crest on the floor of Santissima Annunziata - the headband originally bore three hammers (symbol of the family's ancestral profession), later replaced by three Ts to represent the acronym of the family motto Tempore tempora tempera (time is a great healer [1]) |

In 1404 Antonio di Puccio Pucci acquired the chapel of San Sebastiano in the church of Santissima Annunziata, in which he placed the precious Piero del Pollaiolo painting of the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (now in the National Gallery, London). Puccio Pucci bought the Cappella della Madonna del Soccorso a few decades later.

The family palazzo still contains one of the four paintings commissioned by Lorenzo the Magnificent from Sandro Botticelli as a gift to Giannozzo Pucci on Giannozzo's marriage to Lucrezia Bini in 1483. These paintings tell the story of Nastalgio degli Onesti and the first three in the narrative are now in the Prado in Madrid. The painting still in Florence shows the use of forks, which were traditionally adopted for the first time in Florence by the Pucci and whosa use Catherine de'Medici then spread right across Europe. It also shows the use of precious tableware and silver vessels, which really existed and were said to be from the workshops of Verrocchio and Pollaiolo.

The Pucci commissioned several works for the churches neighbouring their palazzo. For the church of San Michele Visdomini, in 1518 Francesco Pucci commissioned Pontormo to paint the Holy family with saints, which was described by Vasari as one of the best paintings by an empolese painter. Whilst he was archbishop of Bologna, cardinal Antonio Pucci commissioned Raphael to paint a scene of The Ecstacy of Saint Cecilia - still in Bologna, it is now at the city's Pinacoteca. At the end of the 16th century Lorenzo Pucci commissioned Alessandro Allori to paint a Marriage at Cana as an altarpiece for the church of Sant'Agata (completed 1600).

The family's palazzo was rebuilt by the grand-ducal architect Bernardo Buontalenti in the second half of the 16th century. Between 1585 and 1595 abbot Alessandro Pucci built the Villa di Bellosguardo, to designs by Giovanni Antonio Dosio - it remained a family property until 1858. The Pucci completed the portico of the church of Santissima Annunziata, in a stylistic unity with the piazza outside (the Pucci device is to be seen on the pavement in front of the entrance and on both sides of the portico) - an inscription on the frieze and a plaque on Via Gino Capponi gives its completion date as 1601.

[Bibliography

| Marcello Vannucci, Le grandi famiglie di Firenze, Newton Compton Editori, 2006]

The Pazzi conspiracy

|

|

Sandro Botticelli and Bartolomeo di Giovanni, fourth episode of Nastagio degli Onesti series, private collection in Palazzo Pucci, Florence (1483)

|

On December 10th 1479, a fugitive of the previous year’s Pazzi Conspiracy — an ill-starred attempt by the Pazzi family to overthrow the Medici — was hanged in Florence.

The Pazzi conspiracy was the most dramatic of all political opposition to the Medici family. The conspiracy was led by the rival Pazzi family of Florence.

In foreign politics Lorenzo made a disastrous error in the 1470s when he attempted to prevent Pope Sixtus IV from establishing a power base in the Romagna. This led to the Medici bank’s loss of the papal account and a conspiracy between members of the pope’s family and the Florentine Pazzi family to overthrow Medici rule. In April 1478 the Pazzi assassinated Lorenzo’s brother Giuliano but failed to kill Lorenzo, and the insurgents, denied support by the citizens, were captured.

Bernardo di Bandino Baroncelli (1453-1480) was a banker for the Pazzi, and one of the Pazzi conspirators who attempted to murder Lorenzo de' Medici and his brother Giuliano. He grew up learning to hate the Medici for the exile of his cousins. As one of the men whom Jacopo de' Pazzi had hired to kill the Medici brothers, he was the one who delivered the first blow to Guiliano. Baroncelli was later captured while attempting to flee to Constantinople, but he managed to escape to San Gimignano. There, Baroncelli was assassinated by Ezio Auditore da Firenze. Moments before his death, he was evidently becoming paranoid of Ezio and Lorenzo, and was found muttering to himself about how to stay safe. He fled upon catching sight of Ezio, but was nevertheless chased down and assassinated.

A Florentine representative quickly sailed for the Ottoman capital to make the arrangements, and returned with the hated Bandini on Dec. 24. Five days later, he was hanged over the side of the Bargello.

Florentine native son Leonardo da Vinci sketched the hanging man (the sketch is now in the Musee Bonnat), diligently noting his clothing.

The conspirators, Francesco de' Pazzi, Bernardo di Bandino Baroncelli, Archbishop Salviati, Vieri de' Pazzi, Messer Jacopo de' Pazzi, Antonio Maffei and Stefano de Bagnone, were depicted in a painting by Sandro Botticelli on either a wall of the Bargello or a wall of the Dogana, part of the government-complex. Rodrigo Borgia, the Pope Alexander VI pressured Florence to remove these lifelike pictures, and they were eventually destroyed in 1494.

Art in Tuscany | The conspiracy

|

|

Leonardo da Vinci, drawing of a hanged

Pazzi conspirator Bernardo di Bandino Baroncelli, 1479

|

| [1] V&A Museum - Hidden Histories

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Damien Wigny, Au coeur de Florence : Itinéraires, monuments, lectures, 1990

|

|

|

|

An image of Temperance, one of the four cardinal virtues, pouring water from one vessel to another,

by by Agnolo Gaddi, Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence[9]

. |

|

|

|

Walking around the Quarter Duomo and Signoria Square

Start this tour from Duomo Square, the religious centre of Florence, where the Duomo, the Baptistery, the Bishop palace, Giotto bell tower are located. This part of Florence was inside the ancient walls. The first Cathedral of the town was outside the city walls and it was San Lorenzo Church, this was built in the 4th century; in the VII century the title of “Cathedral” passed to Santa Reparata which in 1296 was rebuilt as Santa Maria del Fiore: the Cathedral we see to day (see description in the section “Churches”). In this period the religious centre was separated from the civic centre with the building of the new civic palace. Palazzo Vecchio (Palazzo della Signoria).

Duomo Square and San Giovanni Square the first with the Cathedral and Giotto Bell tower, and the second with San Giovanni Baptistery, make up the most important religious complex of Florence. Before visiting the single monuments have a walk around the two squares and see the other buildings. On the corner with Via Calzaioli you can see the “loggia del Bigallo” a marble elegant loggia by Ambrogio di Rienzo (1353 – 1358) with large decorated arches and parts of frescoes.

Walking in Tuscany | Florence | Quarter Duomo and Signoria Square

|

Lastra a Signa- Villa di Bellosguardo

|

|

|

In the 16th century, in one of the most beautiful areas of the hills around Florence, abbot Alessandro Pucci had a villa built for himself which in its structure would fully represent the mannerist ideal in vogue at the time. In addition to the villa, which was originally completely frescoed inside and out, a garden was also laid out and an extensive park with beautiful trees and sculptures of animals dotted in amongst. These grounds were designed by Tribolo. In 1906 the villa was purchased by the world-famous Italian tenor Enrico Caruso who, totally enamoured of the beauty and peace his new home offered, arranged for the villa to be restructured, restored and embellished with works of art. As a result of the work done the villa acquired the appearance it retains to this day. Since 1955 the villa, garden, park and farm have been owned by the town of Lastra a Signa. It is run by the Villa Caruso Association, which organises concerts and other performances, exhibitions and visits.

[Source: | www.cultura.toscana.it]

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia articles Loggia dei Lanzi and Pucci family published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Loggia dei Lanzi |

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()