| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Siena | Ospedale Santa Maria della Scala

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala, one of Europe’s oldest hospitals, is situated in Siena, in front of the Duomo. Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala takes its name from the steps, scala, leading up to the cathedral.

This large complex, located in the heart of Siena, conserves extraordinarily intact testimonials of thousands of years of history.

The hospital was founded by the Cathedral's priests across the Via Francigena to house the pilgrims coming from France and northern Europe to Rome. Constructed along the Via Francigena, Santa Maria della Scala was one of the first hospitals in Europe, with its own organization set up to care for pilgrims, assist the poor and provide for abandoned children.

The museum's most impressive cultural gem is Pilgrims Hall, a vast arched room near the main entrance where exhausted pilgrims were cared for on their way to Rome.

|

| |

|

As early as the twelfth century, Siena had gained for itself a role of international importance in terms of polities, art, religion and commerce, due to its position on the Via Francigena, the 'main highway' of the Middle Ages, which played a crucial part in the construction of modem European identity, bringing together cultures, languages, customs and traditions. The Francigena ran right across the city from Porta Romana to Porta Camollia, linking Rome with the main towns of Northern Europe.

Along this section of the Via Francigena running through Siena, some fifty hospices sprang up, where pilgrims could be given shelter and care on their way. Of various sizes, nearly all of these were established as a result of legacies or donations. The most famous was that of Santa Maria della Scala, situated within the city itself.

Built right opposite the cathedra, Santa Maria was one of the first examples of a xenodochium (a pilgrims hospice) and a hospital in Europe. It had its own autonomous organization and was arranged to take in wayfarers and to look after abandoned children and the poor. Mentioned in a deed of gift as early as 1090, the Santa Maria hospital was founded by the cathedral canons, even if a medieval Sienese legend tells of a mythical founder by the name of Sorore, a cobbler, who died in 898.

After 1195 the running of the hospital became progressively more secular, passing from the canons of the cathedral to the hospital friars, also known as oblates. These were people who had left their lives of comfort to devote themselves to charitable works. At the head of the hospital structure was the rector, elected until the beginning of the fifteenth century by the Chapter of Friars, and from then on directly by the Commune of Siena. The election of the rector in this new manner basically transformed the position into a public office, assigned by ballot by the Consistory and later by the Balìa (two local government bodies). Besides, the Commune of Siena had already been involved in the hospital ever since its origins, supporting it and recognizing the institution's objectives as its own. Before being nominated, the rector was obliged to donate all his assets to the hospital.[1]

|

The Santa Maria hospital was founded by the cathedral canons. However, a medieval Sienese legend tells of a mythical founder, a cobbler by the name of Sorore, who died in 898. Thanks to the legacies of Siena's noble families and to the considerable alms that poured into the hospital funds, the Santa Maria quickly gained importance in the economy of the Sienese Republic. In addition, a large number of agricultural properties, known as grance, were scattered throughout the territory of the Republic, and for centuries these provided further support to the hospital's intense activity. Following bequests and donations between the late Thirteenth and the early Fourteenth centuries, the Hospital began to divide and organise its own landed property into large agricultural estates. These fortified granaries of the Sienese countryside were called Grancia or grance. They represented a huge patrimony that covered extensive areas of the Val d’Orcia, Val d’Arbia, Masse, Crete and Maremma, and, as a whole, represented the largest concentration of land of the Sienese state. [1]

Many great Sienese artists worked for Santa Maria della Scala at some time, making it the city's third important centre of art, together with the Duomo (cathedral) and the Palazzo Pubblico (Town Hall).

In the Fourteenth-century section of the edifice – originally used to shelter the numerous travellers who arrived in Siena for the Holy Year of 1300 declared by Pope Boniface VIII – which later served as a hayloft, the first part of the exposition of Jacopo della Quercia’s original Fonte Gaia fountain was opened in October 1998.

The collection in Siena's new modern archaeology museum, recently incorporated into the Santa Maria della Scala complex, is small, and while there's nothing of earth-shattering significance, there are some surprisingly good pieces for a museum hardly anyone knows exists.

But the most prestigious example of Sienese art in the Santa Maria della Scala complex, is the Pellegrinaio ward or 'pilgrims' hospice', built in the second half of the 14th century and decorated almost a century later with an important fresco cycle devoted to the history of the hospital. Artistic Treasures include a famous fresco cycle (now lost) with Histories of the Virgin, on the façade, by Simone Martini, Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti (1335); the series of frescoes with the Stories of the Hospital in the Pellegrinaio Hall, by Domenico di Bartolo, Lorenzo Vecchietta and Priamo della Quercia, the old sacristy, also decorated by Vecchietta, the Manto Chapel, with a lunette by Domenico Beccafumi, the 15th Fonta Gaia by Jacopo della Quercia, and the decoration of the large apse by Sebastiano Conca (late 18th century).

Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala

Open every day 10.30 - 18.30

Website of Santa Maria della Scala, Siena | www.santamariadellascala.com

'The progressive recovery of the entire Santa Maria della Scala complex, and its functional rehabilitation through museums, activities and services is now considered to be one of the most significant multi-purpose cultural achievements in the world. The complex houses (and in the future will house even more) cultural activities, such as a series of museums and exhibition areas, as already mentioned, and an International Center for Restoration Research. Completing and further enriching the center's cultural mission are a variety of events such as restoration workshops and educational activities, research, services and business, in keeping with visitor demand.' |

|

Santa Maria della Scala served as a hospital from the 10th Century until 1996

Façade of the hospital at the beginning

of the 20th century

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

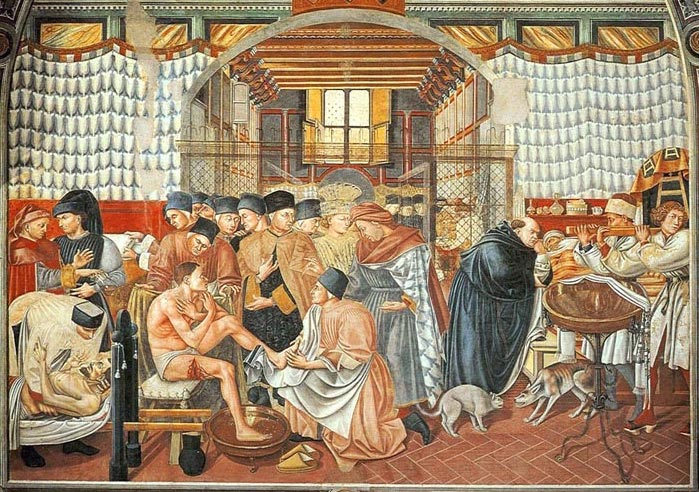

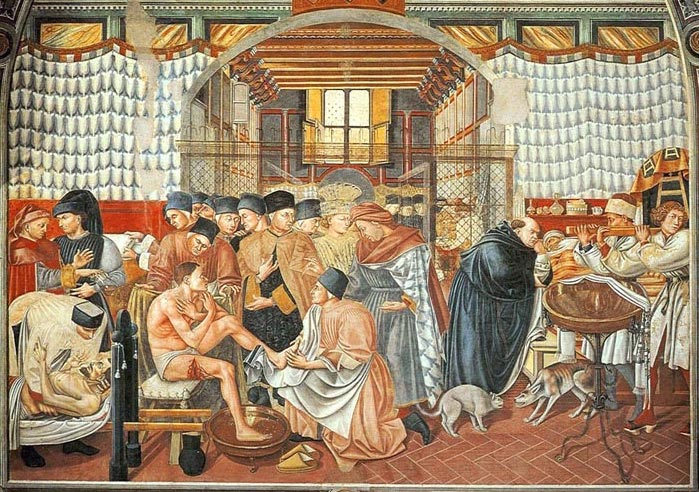

Domenico di Bartolo, Care of the Sick, 1441-42, fresco in Spedale di Santa Maria della Scala, Siena

|

The Pellegrinaio's evident French influence - there are many examples of longitudinal spaces in Cistercian buildings from the twelfth century onwards - further confirms the city's intense contact with other parts of Europe, favored by its position on the Via Francigena.

The building of this ward dates to the third decade of the fourteenth century, although its structural form was not finalized until around 1380. At the beginning of the fifteenth century (1405), the unsafe wooden roof was replaced with the present six vaults, and the original capitals were carved, these too of clear French influence.

The last bay, near the window that overlooks the valley below - the Fosso di Sant'Ansano - was added in the second half of the sixteenth century (1577), as was the decoration of the two side walls, the back wall, and the ceiling. The painting cycle, whose iconographic program was conceived by rector Giovanni di Francesco Buzzichelli, was carried out on the four central bays of the Pellegrinaio. In the first bay, however, some traces of fresco can still be seen, probably the remains of previous works depicting Episodes from the Life of Tobias. These paintings were executed before 1440 by Lorenzo Vecchietta and Luciano di Giovanni da Velletri but were later destroyed because they were thought to be outmoded and unsuitable to represent adequately the history and life of the Santa Maria hospital, which in the meantime was becoming more prestigious and powerful.

To carry out this project, the rector called on two Sienese painters (Vecchietta and Domenico di Bartolo, joined by Priamo della Quercia for one of the episodes). Both of these artists were perfectly aware of, and particularly attracted by the new Renaissance styles, and had had significant experience outside their city. For example, Vecchietta had worked with Masolino in Castiglione Olona.

|

| |

|

|

Vecchietta. The Founding of Spedale di Santa Maria della Scale and The Vision of Santa Sorore

|

| |

Vecchietta was born in Castiglione d'Orcia, and lived in Siena. Much of his work may be found there, particularly at the Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala, lending him yet another name: pittor dello spedale (or 'painter of the hospital').

For the Pellegrinaio (Pilgrim Hall) at the Hospital complex, Vecchietta painted a series of frescoes, along with Domenico di Bartolo and Priamo della Quercia, including The Founding of the Spedale and The Vision of Santa Sorore, depicting a dream of the mother of the cobbler Sorore, the mythical founder of the Hospital.

|

| |

The Founding of Spedale di Santa Maria della Scale

|

|

|

| |

This fresco is located on the east wall of the Pellegrinaio, situated on the ground floor of the hospital. In this painting Vecchietta set the complex scene in what appears to be a vaulted church. This allowed him to place the central narrative event within the nave of this church. Here the cobbler, Sorore, the mythical founder of the Spedale, is shown describing to one of the canons of the cathedral the vision that his mother was alleged to have experienced before his birth. Behind these two figures, in the space of the domed crossing, appears the vision itself - the Virgin welcoming infants who have reached heaven by climbing up the hospital's emblem of a ladder. The right-hand aisle of the church, meanwhile, acts as the setting for the first occasion when Sorore brought a foundling to one of the cathedral canons and received money for the upkeep of the child. The entire edifice is fronted by an impressive facade whose style with its antique detail of fluted piers, ornate capitals and frieze is unequivocally Renaissance. Perspective has been employed to great effect, both on the pavement of the church and in the recession of the building itself.

|

|

Vecchietta. The Founding of Spedale di Santa Maria della Scale. |

| |

The Vision of Santa Sorore

|

|

|

| |

One of the Santa Maria's many functions, that of taking in abandoned children, is shown in the first fresco on the left, painted by Lorenzo Vecchietta and representing Episodes from the Life of the Blessed Sorore (ca. 1441). The painter portrays the dream experienced by the hospital's mythical founder's mother who, even before the birth of her son, predicted his charitable vocation and his responsibility for the foundation of the prestigious hospital institution.

|

|

|

| |

Domenico di Bartolo was born in Asciano. According to Vasari, he was a nephew of Taddeo di Bartolo. He was employed by Vecchietta in the masterpiece fresco The Care of the Sick in the Pellegrinaio (Pilgrim's Hall) of the Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala in Siena [1]. It portrays wealthy donors visiting the hospital to men washing the ill, and a fatty friar hearing confession. In the Care of the Sick Domenico combines specific portraiture with a sensitive treatment of the nude figure. The unidealized bodies of the sick man being placed in bed and the wounded man being washed rank among the most naturalistic figures in Quattrocento painting.

In 1434, Domenico di Bartolo painted also a fresco panel of Emperor Sigismund Enthroned for the Siena Cathedral. |

|

Healing the sick Healing the sick, fresco by Domenico di Bartolo. Sala del Pellegrinaio (hall of the pilgrim), Hospital Santa Maria della Scala, Siena.

|

| |

|

| |

Almsgiving, fresco by Domenico di Bartolo. Sala del Pellegrinaio (hall of the pilgrim), Hospital Santa Maria della Scala, Siena

|

Domenico di Bartolo, The Bishop Giving Alms (1442-1443)

|

| |

Domenico di Bartolo began this work on the opposite wall, probably taking over from Vecchietta when the latter interrupted the decoration of the Pellegrinaio). This scene of the Limosina (Almsgiving) represents a pompous procession where the bishop, in the center and mounted on his heavy roan horse, is about to knock over one of the master workers waiting outside the work site of the Hospital. The minute details showing the organization of the work site on the right and the clothes the figures are wearing are of particular interest. The huge building in the center and those around it seem to be gothic elements while the others are typical of the Renaissance period; this probably depends on the artist's experiences in building sites in the north.

|

| |

A third fresco by di Bartolo, of a paupers' supper, was severely damaged in the 19th century when hospital administrators had a window cut through it. As in the other scenes on the same wall these painting illustrates another disposition of the statute of Santa Maria della Scala, and that is “to provide hospitality and means and usefulness to the old and poor veterans of the city and county of Siena”. Once again, Domenico di Bartolo dwells upon the refined clothing of certain figures, on various particulars of the dinner and on the prospective, which is strongly centralized and underlined by elegant columns, capitals, arches and mouldings.

|

| |

|

|

Matteo di Giovanni, Massacre of the Innocents, Massacre of the Innocents, 1482, The Chapel of our Lady, Ospedale Santa Maria della Scala, Siena

|

Matteo di Giovanni, Massacre of the Innocents

|

| |

The Chapel of our Lady also holds one of the four versions of the Massacre of the Innocents, which Matteo di Giovanni, an artist born in Sansepolcro, and one of the leading figures of fifteenth-century Sienese art, painted in the course of a decade. The canvas on deposit at Santa Maria della Scala, is the work made by the artist in 1482 for the church of Sant'Agostino in Siena.

Matteo di Giovanni painted four monumental compositions of the Massacre of the Innocents, three for Sienese churches and one in inlaid stone for the pavement of the Duomo.

The picture painted for Sant'Agostino, like the final one made for the Basilica of Santa Maria dei Servi (also known as San Clement), seems to present some iconographic innovations, probably the fruit of the terrible echo, still resonating among his contemporaries, of the siege and massacre perpetrated by the Turks at Otranto in 1481.

Here, in the place of clothing and armor with a classical imprint, oriental styles prevail, and even in the facial features we can detect some 'Moorish' characteristics. The entire scene is marked by ferocity and cruelty, emphasized also by the range of colors used. The arches and columns of Herod's palace suggest that the artist had visited Rome. He has left no foreground space and every inch of Herod's hall is occupied by screaming mothers, dead or dying babies, and bloodthirsty soldiers. The marble pavement is covered by infant corpses. Impassive courtiers flank Herod's throne, while the gloating king is portrayed as a monster: one hand is outstretched to order the butchery; the other, like a claw, clutches the marble sphinx on the arm of his thronThe panel for the church of Sant'Agostino was originally part of an altarpiece 'in the ancient style', topped by a gold ground lunette which was removed in the seventeenth century, while the panel itself, although moved to a different place, always remained inside the church.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

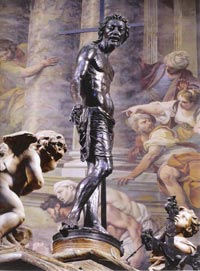

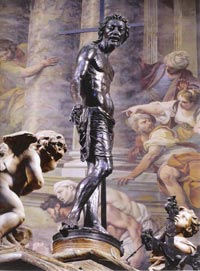

Church of the Santissima Annunziata, high altar with Vecchietta's Risen Christ

|

Church of the Santissima Annunziata

|

|

|

| |

The church of the Santissima Annunziata was built on an older nucleus, at the end of the Thirteenth century, when Santa Maria was speeding up its expansion and the complex began to split up into various units that were assigned to the various activities carried out inside.

The church was completely renovated in the second half of the Fifteenth century by various artists, among whom Francesco di Giorgio Martini, with the decoration of the apse and the coffered ceiling.

In the second half of the Seventeenth century the high altar was rebuilt and two side altars were added, with works by Giuseppe Mazzuoli, two paintings on canvas by Pietro Locatelli (Assumption) and Giovanni Maria Morandi’s Annunciation.

At the centre of the high altar one can admire a bronze work of outstanding artistic interest, Lorenzo Vecchietta’s Risen Christ, dated and signed by the artist in 1476. It is a veritable masterpiece of Renaissance sculpture, frequently related by the critics to Donatello’s Sienese works.

In 1730 Sebastiano Conca, a painter of consolidated fame, decorated the church’s grand apse. |

|

Vecchietta, Risen Christ, c. 1476, Bronze, Chiesa dell'Ospedale della Scala, Siena Vecchietta, Risen Christ, c. 1476, Bronze, Chiesa dell'Ospedale della Scala, Siena |

| |

For the high altar of the Church of the Santissima Annunziata, within the Hospital complex, he created a bronze figure of the Risen Christ (signed and dated 1476). The Risen Christ (Sta Maria della Scala, Siena, 1476) has something of Donatello's sinewy expressiveness.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Pool of Bethesda, high altar and an apse-covering fresco by Sebastiano Conca (1732), in the church of the Ospedale della Scala, Siena

|

Sebastiano Conca, Pool of Bethesda, high altar and an apse-covering fresco by (1732)

|

| |

The Pool of Bethesda develops the Rococo style of the Coronation of St Cecilia, and the softness and transparency of the colour suggest both the influence of Solimena and of Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari and Benedetto Luti.

His fresco with the Provative Pool accurately illustrates a passage of John’s Gospel in which the sick gather near the pool hoping for a miraculous healing. This fresco, which represents Santa Maria della Scala’s last artistic commission, has been recently restored.

Conca was one of the most successful painters working in Rome in the first half of the 18th century and was celebrated throughout Europe. He painted altarpieces and frescoes, creating an accomplished style that mediates between the grandeur of the late Baroque and the academic manner of Carlo Maratti. |

Downstairs are rooms documenting the restoration of Jacopo della Quercia's Fonte Gaia with plaster casts, and the Oratorio di Santa Caterina della Notte. This suggestive place, located in the heart of the Santa Maria della Scala complex, where St Catherine used to stop in prayer and comforted the sick, still conserves the same intensity and atmosphere that for many centuries have accompanied the religious fervour of the Saint’s countless devotees.[3]

The Corticella, or little courtyard, now functions as a junction between the various routes through Santa Maria della Scala. Built during the fourteenth century, it is reached from the internal road and from here. was easy to go on to the rooms used for meals and the storerooms. The recent work of restoration and renovation has given new unity and functionality to this space, which was originally in the open air and now gives access to the confraternities and the old hay rooms on one side and to the beginning of the descent to the 'tunnels' on the other. The Oratory of the Company of Saint Catherine of the Night was decorated mainly in the 17th century by Rustici and Rutilio Manetti but also contains a rich Madonna and Child with Saints, Angels, and Musicians by Taddeo di Bartolo (ca. 1400) in the back room, and St Catherine of Siena protects some of the Confraternity of the Night Oratory, attributed to Benevuto di Giovanni. |

|

|

| |

|

Ospedale Santa Maria della Scala

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Siena, Ospedalei Santa Maria della Scala |

|

Spedale di Santa Maria della Scala (facciata) |

|

Capitoline Wolf in front of the Compleso Santa Maria della Scala

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pellegrinaio di Santa Maria della Scala

|

|

Domenico di Bartolo, 1442-1443, Costruzione delle mura dello spedale, Pellegrinaio di Santa Maria della Scala

|

|

Sala dell’ospedale con gli ospiti nei lettini. Il Pellegrinaio è stata corsia ospedaliera fino al 1995

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chiesa della Santissima Annunziata

|

|

Chiesa della Santissima Annunziata, interiore

|

|

Cristo Risorto, altare dellaChiesa della Santissima Annunziata dello Spedale di Santa Maria della Scala

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cappella del Sacro Chiodo o Sagrestia Vecchia

|

|

Madonna della Misericordia di Domenico di Bartolo |

|

Andrea di Bartolo, Crocifissione e Madonna della Misericordia , Cappella delle Fanciulle, Museo Santa Maria della Scala, Siena

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cappella delle Reliquie |

|

Cappella delle Reliquie, l'affresco ritrovato: si vedono il Pantheon, Castel Sant'Angelo, il Colosseo

|

|

Cappella delle Reliquie, Incontro alla Porta d'Oro di Beccafumi |

Podere Santa Pia is embedded in the tranquility of the Tuscan country and let you enjoy great views of the Maremma. It is suitably located only 20 kilometers from the highway Grosseto - Siena. Although this is off the beaten track it is the ideal choice for those seeking a peaceful, uncontaminated environment. Podere Santa Pia is embedded in the tranquility of the Tuscan country and let you enjoy great views of the Maremma. It is suitably located only 20 kilometers from the highway Grosseto - Siena.

Tuscan Holiday houses | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

Overlooking the vineyards and beautiful hills of the Maremma |

|

|

|

|

[1] Following bequests and donations between the late Thirteenth and the early Fourteenth centuries, the Hospital began to divide and organise its own landed property into large agricultural estates. These fortified granaries of the Sienese countryside were called Grancia or grance. They represented a huge patrimony that covered extensive areas of the Val d’Orcia, Val d’Arbia, Masse, Crete and Maremma, and, as a whole, represented the largest concentration of land of the Sienese state. For nearly five centuries, they constituted the main source of sustenance of Santa Maria’s economic structure, until the property was alienated in the second half of the Eighteenth century.

Grancia di Cuna is one of the best preserved of Tuscany. The Cuna Grange is one of the best preserved medieval fortified farms. Already in the 12th century, there existed a Spedale that lodged and assisted pilgrims and merchants travelling along the Via Francigena. In the 13th century Grancia di Cuna became the property of the Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena, and the building underwent numerous enlargement and remodelling initiatives. In 1314 the granary was fortified to safeguard the stores of grain and other cereals. T he church dedicated to the Santi Giacomo e Cristoforo was remodelled. Today it stands just outside the circle of outer walls.

Other famous buildings with similar functions are the Serre Grange at Rapolano, now the site of a Museum, and the Montisi Grange, privately owned.

In the centre of Val d'Orcia, between Piernza and Bagno Vignoni, the Castello di Spedaletto (Castle of Spedaletto) was built by the priest Ugolino da Rocchione as a fortified farm and as a place to guest the pilgrims. From 1236 the castle was one of the hospitals of Santa Maria della Scala of Siena and it was called Spedale del Ponte dell 'Orcia (Hospital of the Bridge of River Orcia).

[2] Thomas Harvey is a professor of geography at Portland State University. His research and teaching interests are in urban geography, local distinctiveness, and landscape stewardship. Each September he explores Tuscany’s hill towns and rural landscapes with a small group of students.

"In the 13th century, cities began to dominate economic activity in Europe. While all cities depend on their immediate hinterlands, the ties of city and country were particularly strong in Tuscany and the Veneto. The feudal order gave way to a system of independent city-states. Each city extended its power into the countryside or contado, in order to control local food supply, raw materials, and urban-rural trade. Power was wrested from feudal families, allegiance was reoriented to the city-state, and rural migrants made their way to cities. The countryside served not only as a resource hinterland; rather the contado became an extension of urban governance and land ownership. While wealth was extracted from the territory, cities in turn provided a measure of protection to rural and village residents, and concepts of citizenship extended beyond the walls of the city. In Siena, nobles with rural landholdings and villas in the contado were required to maintain houses in the city for at least part of the year, thus reinforcing city-country ties.

By the 13th century, Siena controlled a vast territory that extended as far as Grosetto to the southwest on the Mediterranean. City-country connections existed with wealthy landowners and extended to the Ospedale de Santa Maria della Scala, a “hospital” —or “hospitality center” —whose original function was to provide food and shelter for travelers on the Via Francigena, the pilgrimage route that led from France to Rome. The first written mention of the Ospedale is in 1090. By the 13th and 14th centuries, in order to feed pilgrims and hospital patients, provide bread to poor families in Siena and the Sienese contado, and generate revenue, the Ospedale managed extensive agricultural landholdings and granaries throughout the territory. The city-country relationship of this major institution reinforced the ties between Siena and its surrounding territory and the ownership of rural land by Siena’s leading families. In 1338-39, when Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted his famous fresco in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico, the essential link between city and country—their governance and their respective landscapes—was established and understood.

Thomas Harvey, Siena & Sustainability: City and Country in Tuscany. Terrain.org: A Journal of the Built and Natural Environments 20 (Summer/Fall 2007).

|

|

Grancia di Cuna

La Grancia Spedaletto

|

[3] The confraternities | From the fourteenth century, meeting under the roof of Santa Maria della Scala, besides the older lay company dedicated to Mary Most Holy, now the Società di Esecutori di Pie Disposizioni, and one named for Saint Jerome, documents indicate a confraternity named after Saint Michael Archangel (later called Saint Catherine of the Night) devoted especially, like the others, to pietas for the deceased. The confraternity was based near me hospital cemetery and the so-called carnaio (chamel house) whose pit, still visible today, stretched from the upper floor, corresponding with Piazza del Duomo, to a level with Piazza della Selva, much lower down.

The confraternity of Saint Catherine of the Night | The home of the brotherhood of Saint Michael the Archangel was therefore situated at an intermediate level, and access to it was gained via an entrance near the Cappella del Manto.

According to tradition this society was later named Santa Caterina della Notte, a name that appears in documents in 1479, because of Saint Catherine's frequent stays here, and at the time when the "disciplinati" meeting under the vaults merged with a confraternity named after Saint Catherine that originally met under the cathedral, and began work to form a new brotherhood.

Until1607 the brotherhood of Saint Catherine occupied the present-day oratory alone, after which they acquired other adjacent rooms and thereby obtained an organized distribution of their headquarters which has remained basically unchanged up to the present.

During this same period the decoration of the oratory was enriched with numerous paintings, including four canvases depicting the life of Saint Catherine. At the end of the seventeenth century new work was undertaken, subdividing the vaults of the oratory into three sections and carrying out an extensive stucco decoration, developed mainly towards the altar wall. In addition, new impetus was given to the decoration scheme with other canvases and furnishings, almost all devoted to Saint Catherine and the Virgin Mary. On the altar itself is 00 interesting Virgin and Child from the end of the 14'" century, probably the society's oldest religious image. On either side are four angels and Saint Dominic and Saint Catherine in Adoration. Besides the numerous paintings, carvings, relics and furnishings, the lay company also preserves a fine panel-painting by Taddeo di BartoIo portraying the Virgin and Child, Four Angels and Saints John the Baptist and Andrew, dated 1400, and four bier headboards showing Saint Catherine Protecting Four Brothers beneath her Cloak, The Resurrected Christ, the Stigmata 0/ the Saint, and the Deposition, attributed to an early sixteenth-century Sienese artist.

Situated in the heart of the ancient hospital complex, these rooms still possess the intensity and atmosphere that has accompanied the religious fervour of the great Sienese saint's many devotees for so many centuries.

(Sources Enrico Toti, (conservatore of Santa Maria della. Scala), Santa Maria della Scala : a thousand years of history, art and archaeology, Siena : Protagon, [2008])

|

|

St Catherine of Siena protects some of the Confraternity of the Night Oratory, on a 16thC coffin panel (one of four, attributed to Benevuto di Giovanni). Maybe from Oratorio di Santa Caterina della Notte. Known since the Fifteenth century as the Confraternity of St Michael, the company devoted itself mainly to pietas towards the dead. |

| The Development of Realistic Painting in Siena-I, by John Pope-Hennessy |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()