| |

|

The Church of San Lorenzo

|

|

|

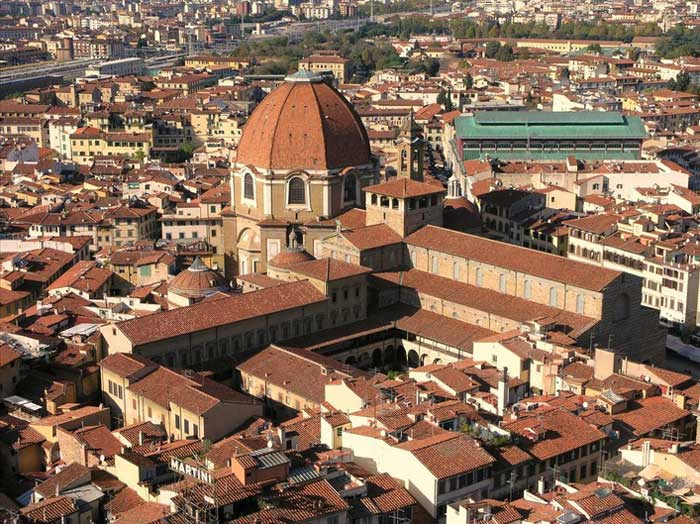

The Church of San Lorenzo, one of the first examples of the new Renaissance style of architecture, was mostly designed by Brunelleschi and paid for, largely, by Cosimo de’ Medici. In return for his generosity and also for the service that he rendered to the Republic, Cosimo is buried in the nave in front of the high altar, the most prestigious place in a church to be interred. He is commemorated by an inscription (see below), Pater Patriae (Father of the State), an honour he received posthumously, in 1464. Honours, however, can be taken away as well as given and the inscription was defaced each time the Medici were exiled (1494 and 1527) and the city regained its republican status. In many respects, the Medici family treated San Lorenzo like a private mausoleum, for so many of its members are buried here. The church was close to the first Medici palace, the home of Cosimo the Elder and Lorenzo the Magnificent, Palazzo Medici Riccardi. In 1444 Cosimo de' Medici had decided to build a family palace in a strategic location at the crossroads between the Via Larga (now Via Cavour) and Via de' Gori, near the churches patronized by the family (San Lorenzo and San Marco) and the Cathedral. Palazzo Medici Riccardi was the first Renaissance building erected in Florence.

|

|

Basilica di San Lorenzo, interior |

The Canons' cloister, the Chiostro dei Canonici

|

The main cloister belonging to the Basilica of San Lorenzo is known as the Chiostro dei Canonici and dates back to the last phase of the 15th century renovation of the complex ordered by the Medici family.The Basilica, serviced by Canons and dedicated to the martyr Laurence, was founded in antiquity and consecrated by St. Ambrose in 393 a. D. In 1418 the Canons' Chapter had the Basilica refurbished and enlarged by Filippo Brunelleschi. Works began in 1419/1420 and were completed, after the master's death, by his disciple Antonio Manetti Ciaccheri who conceived the two-storey loggia with the round arch arcade on the ground floor and the architrave on the upper one (1457-1460). Entering on the right, a statue of the Madonna and Child in the style of Desiderio da Settignano is immediately visible.The plaster statue is surrounded by a glazed terracotta frame and is dated 1513. Various plaques follow on the same side, most notably the one commemorating the renovations undertaken in the Basilica in 1742 and commissioned by Anna Maria Ludovica de'Medici. In the corner, at the far end of this side of the cloister, there are the stairs to the upper floor and to the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana; a niche in the wall at the left of the base of the stairs houses the marble statue of the Bishop of Como, the historian and collector Paolo Giovio (1483-1552), realized by Francesco da Sangallo in 1560. Always at the left of the stairs, further along the cloister, there is the entrance to the crypt which holds the tombs of Cosimo de'Medici the Elder and of the sculptor Donatello whilst through a gabled door there is the Canons' Chapter Chapel with late 15th century carved wooden pews.

Vestibule

|

|

Chiostro di San Lorenzo, Firenze |

This is the Vestibule or entrance-hall of the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, the library whose core collection comprised the manuscripts collected by Cosimo the Elder (1389-1464) with the help of some of the most famous humanists of the time. This collection grew considerably under Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-1492) and was opened to the public, according to the statesman's wishes, by his nephew, Giulio (1478-1534) who ascended the papal throne as Clement VII (1523). The task of projecting and building the library was entrusted to Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564). Works began in 1524 and went on until 1534, when Michelangelo left Florence and Pope Clement VII died. Under Cosimo I (1519-1574) the building of the library was resumed and in 1571 it was opened to the public. The Vestibule's main feature is its verticality: the walls are divided into three sections decorated by double columns, scroll-shaped corbels, gabled niches framed by pilasters which taper downward in an usual fashion.The staircase, originally conceived by Michelangelo in walnut, was realised by Bartolomeo Ammannati in 1559 in 'pietra serena', a type of grey sandstone, following a wax model by Michelangelo himself. Its tripartite structure, including a central flight with elliptically shaped stairs, is quite unique. Michelangelo intended the Vestibule to be a dark prelude to the brightness of the Reading Room. It remained incomplete until the beginning of the 20th century when finally the facade was accomplished with its series of blind windows. On the same occasion the ceiling was covered by a cloth painted by the Bolognese artist Giacomo Lolli (1857-1931), depicting motifs imitating the carved wooden ceiling of the Reading Room.

|

|

Vestibule or entrance-hall of the Biblioteca Medicea |

The reading room

|

|

The Laurentian Library (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana), the reading room

|

The Reading Room, which unlike the Vestibule develops horizontally, hosts two series of wooden benches, the so-called plutei, which functioned as lecterns as well as book-shelves. They were designed by Michelangelo and, according to Giorgio Vasari, work of Giovan Battista del Cinque and Ciapino.The collection once kept here is unique for its philological and artistic value. The manuscripts and printed books lied horizontally on the lecterns and on the shelves and were distributed by subject (Patristics, Astronomy, Rhetoric, Philosophy, History, Grammar, Poetry, Geography); the wooden panels placed on one side of each bench listed the titles of the items chained therein. This display was maintained until the beginning of the 20th century, when the manuscripts (the printed books were given to the Magliabechiana Library, now Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze in 1783) were transferred downstairs, in the vaults were they are still housed. Always according to Vasari, the linden ceiling was carved in 1549-1550 by Giovan Battista del Tasso and Antonio di Marco di Giano (also known as 'Il Carota'), following earlier drawings by Michelangelo. The floor, instead, in red and white terracotta was realised from 1548 by Santi Buglioni according to a design by Tribolo. Its centre echoes the ornamental and symbolic designs found in the ceiling, which allude to the Medici dynasty. |

|

Desk and bench combination. Each row had a specific topic and a list of books assigned to that desk. |

|

|

|

|

|

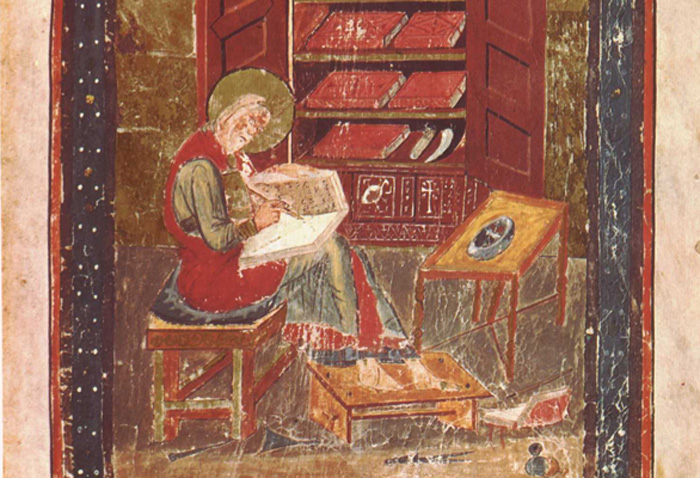

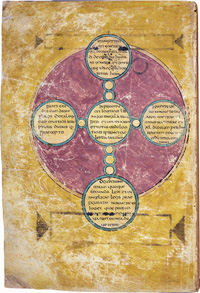

The Codex Amiatinus: the earliest surviving complete Bible in the Latin, long kept in the abbey of Monte Amiata, Abbadia San Salvatore

|

The manuscript, the Codex Amiatinus, long kept in the abbey of Monte Amiata, Abbadia San Salvatore in Tuscany, from which its name is derived, is preserved in the Laurentian Library (Bibliotheca Medicea Laurenziana).

It is missing the Book of Baruch. It was produced in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria as a gift for the Pope, and dates to the start of the 8th century. The Codex is also a fine specimen of medieval calligraphy, and is now kept at Florence in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana (Cat. Sala Studio 6).

Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana

Piazza San Lorenzo n° 9 - 50123 Firenze

Address: Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Piazza san Lorenzo, 9

The Library, which is part of the monumental complex of S. Lorenzo, can be reached through the entrance at the left of the church’s doorway, is located in the town centre and is easily accessible on foot or by bus. No private traffic is allowed in the area.

It is possible to reach the Library from S. Maria Novella train station (around 5-10 minutes).

On foot: through Piazza dell’Unità and along Via del Melarancio; when in Piazza Madonna degli Aldobrandini walk along the Basilica of S. Lorenzo and then up the flight of steps.

B y bus: from the Station (Via Valfonda side) take bus n. 22 (direction Via Vecchietti) and get off at the stop called ”Negozio flow“ .

|

|

|

Ben Nicholson, Jay Kappraff, Saori Hisano - The Hidden Pavement Designs of the Laurentian Library, pp. 87-98 in Nexus II: Architecture and Mathematics, ed. Kim Williams, Fucecchio (Florence): Edizioni dell'Erba, 1998.

'In 1774, a portentous accident occurred in the Reading Room of the Laurentian Library, designed by Michelangelo. The shelf of desk 74, overladen with book, gave way and broke. During the course of its repair, workmen found a red and white terra cotta pavement hidden for nearly 200 years beneath the floorboards. The librarian had trapdoors, still operable today, built into the floor so future generations could view these unusual pavements. In 1928 another mishap resulted in the exposure of the entire pavement, which allowed photographs to be made of the fifteen panels on the West side of the library before the wooden floor was replaced.'

The Codex Amiatinus | www.lametaeditore.com

Damien Wigny, Au coeur de Florence : Itinéraires, monuments, lectures, 1990

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()