|

|

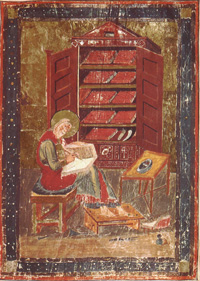

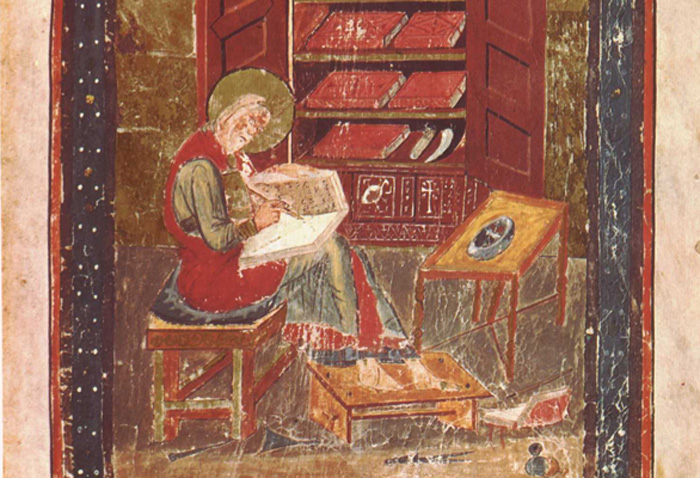

Codex Amiatinus The illuminated manuscript Codex Amiatinus (ad 689–716) in Florence contains an illustration of the prophet Ezra writing in front of a cupboard with open doors that reveal shelves holding books |

|

The Codex Amiatinus |

| The Codex Amiatinus is the earliest surviving manuscript of the complete Bible in the Latin Vulgate version, and is considered the most accurate copy of St. Jerome's text. It was used in the revision of the Vulgate by Pope Sixtus V in 1585-90. Ceolfrith, abbot of the twin monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow in Northumbria, had three copies of the Bible made from a model coming from Cassiodorus' Vivarium. Of these only the Codex Amiatinus (ms. Laur. Amiat. 1) survives intact today. This manuscript, written between the end of the seventh and the beginning of the eighth centuries by at least seven or eight scribes, is exceptionally large. It is composed of 1029 parchment leaves, measures 540 x 345 mm and weighs around 50 kilos. Its extraordinary interest derives not only from these external characteristics, but also because it is the most ancient and complete witness to the Vulgate Latin Bible. The Codex Amiatinus was carried to Rome by Ceolfrith as a gift to Pope Gregory II in 716. At an undeter-mined date, though certainly before the beginning of the eleventh century, the manuscript came to the Monastery of San Salvatore on Mount Amiata, where it remained for at least seven centuries, except for a brief period in Rome when it was collated by the commission in charge of the Sistine Bible (1590). Kept in the reliquary cupboard of the Amiatine monastery, it fell victim to the Suppression of the Monasteries ordered by Grand Duke Leopold and was confiscated in 1782. Two years later it was assigned to the Laurentian Library where first the Medicis and then the House of Lorena hoarded the most important witnesses of Western culture in their possession. The imposing structure of this manuscript, its venerable age and the value of its great miniatures (of which the most famous is that portraying Ezra copying the Holy Scriptures) have ensured it's strict conservation. Thus, the manuscript is still in excellent conditions. These same features have, however, made consulting or exhibiting the manu-script extremely difficult as well as carrying out its accurate reproduction.[1] |

||

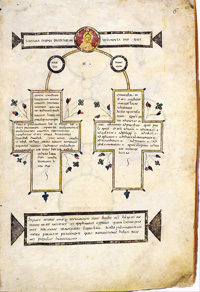

| The symbol for it is written am or A (Wordsworth). It is preserved in an immense tome, measuring 19¼ inches high, 13⅜ inches in breadth, and 7 inches thick, and weighs over 75 pounds — so impressive, as Hort says, as to fill the beholder with a feeling akin to awe.[2] [3] It contains Epistula Hieronymi ad Damasum, Prolegomena to the four Gospels. Some consider it, with White, as perhaps "the finest book in the world"; still there are several manuscripts which are as beautifully written and have besides, like the Book of Kells or Lindisfarne Gospels, those exquisite ornaments of which Amiatinus is devoid. It qualifies as an illuminated manuscript as it has some decoration including two full-page miniatures, but these show little sign of the usual insular style of Northumbrian art and are clearly copied from Late Antique originals. It contains 1040 leaves of strong, smooth vellum, fresh-looking today despite their great antiquity, arranged in quires of four sheets, or quaternions. It is written in uncial characters, large, clear, regular, and beautiful, two columns to a page, and 43 or 44 lines to a column. A little space is often left between words, but the writing is in general continuous. The text is divided into sections, which in the Gospels correspond closely to the Ammonian Sections. There are no marks of punctuation, but the skilled reader was guided into the sense by stichometric, or verse-like, arrangement into cola and commata, which correspond roughly to the principal and dependent clauses of a sentence. From this manner of writing the script is believed to have been modeled upon the Codex Grandior of Cassiodorus,[4] but it may go back, perhaps, even to St. Jerome. Page with dedication; "Ceolfrith of the English" was altered into "Peter of the Lombards"

|

||||

|

|

|

||

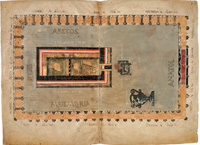

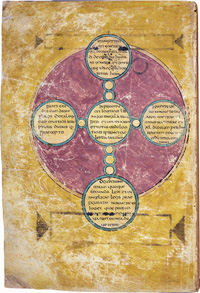

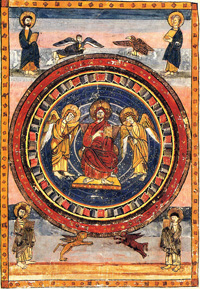

| Maiestas Domini (Christ in Majesty) with the Four Evangelists and their symbols, at the start of the New Testament; page from Codex Amiatinus (fol. 796v), Firenze, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana. | ||||

Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana Piazza San Lorenzo n° 9 - 50123 Firenze The Codex Amiatinus | www.lametaeditore.com Further reading Ferdinand Florens Fleck, Novum Testamentum Vulgatae editionis juxta textum Clementis VIII. Romanum ex Typogr. Apost. Vatic. A 1592 accurate expressum (Lipsiae 1840). Constantinus Tischendorf (1854). Codex Amiatinus. Novum Testamentum Latine interprete Hieronymo. Lipsiae: Avenarius and Mendelssohn. D. J. Chapman, Notes on the Early History of the Vulgate Gospels, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1908. The City and the Book: International Conference Proceedings, Florence, 2001. Alphabet and Bible: From the Margins to the Centre. Paper at Monte Amiata, 2009. Makepeace, Maria. "The 1,300 year pilgrimage of the Codex Amiatinus". Umilta Website. Retrieved 2006-06-07. Contains link to facsimile project, as well. H. J. White, The Codex Amiatinus and its Birthplace, in: Studia Biblica et Ecclesiasctica (Oxford 1890), Vol. II, pp. 273–308. reprint from 2007 [1] The Codex Amiatinus | www.lametaeditore.com [2] H. J. White, The Codex Amiatinus and its Birthplace, in: Studia Biblica et Ecclesiasctica (Oxford 1890), Vol. II, p. 273. [3] Richard Marsden, Amiatinus, Codex, in: Blackwell encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Michael Lapidge,John Blair,Simon Keynes, Wiley-Blackwell, 2001, s. 31. [4] Dom John Chapman, The Codex Amiatinus and the Codex grandior in: Notes on the early history of the Vulgate Gospels, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1908, pp. 2–8.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

| Wine regions | Podere Santa Pia |

Siena, Palio |

||

Siena, Duomo |

Siena, Palazzo Sansedoni |

Corridoio Vasariano, Firenze |

||

Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence |

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence |

Florence, Duomo |

||

This article incorporates text from Wikipedia article Codex Amiatinus published under the GNU Free Documentation License, and from Manuela Vestri, La Bibbia Amiatina | The Codex Amiatinus.

| ||||