| |

|

Niccolò di Segna (died around 1348) was an Italian painter from Siena. His activity is documented starting from 1331. Niccolo di Segna began his career in the workshop of his father, Segna di Buonaventura.

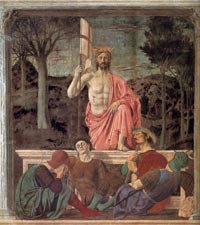

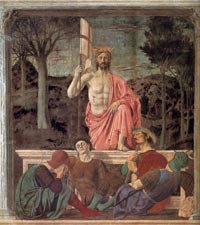

Influenced by Duccio di Buoninsegna and Simone Martini, he was an exponent of the Sienese School. He collaborated with Pietro Lorenzetti to the frescoes in Santa Maria dei Servi (Siena) and painted. Other works by him can be found in the Pinacoteca Nazionale at Siena (Madonna della Misericordia, Madonna with Child, "St. Michael Archangel and others), in the Cathedral of Sansepolcro (Resurrection Polyptych, at the high altar), the Diocesan Museum of Cortona and other collections in Italy and abroad.[1] Behind the high altar of Sansepolcro's cathedral is Niccolò di Segna's polyptych, whose Ressurection of Christ scene heavily influenced Piero della Francesca's famous version now in the Museo Civico.

|

|

Niccolò di Segna, Resurrezione, 1348 circa, Duomo di Sansepolcro

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Sansepolcro Resurrection

|

| |

The cathedral in Sansepolcro contains a gilded polyptych of the Resurrection (14th century), attributed to Niccolo di Segna. The central figure of Christ stands in a pose so similar to Piero della Francesca's Ressurection in the Museo Civico, that many feel della Francesca must have studied this first. Christ miraculously rises from his tomb while the Roman guards sleep. The viewer sees the framing portico and the soldiers from below, but has a head-on view of the seminude muscular figure of Christ.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Niccolò di Segna, Polittico della Resurrezione (dettaglio del Cristo in una grande mandorla blu) |

|

Niccolò di Segna, Polittico della Resurrezione (dettaglio del Cristo circondato da dieci cherubini) |

|

Niccolò di Segna, Polittico della Resurrezione (dettaglio di San Benedetto e Santa Agnese con la sua pecora)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Niccolò di Segna, dettagli del polittico della Resurrezione, 1348 circa, Duomo di Sansepolcro

|

Resurrection by Niccolò di Segna,

Duomo in Sansepolcro

|

|

Piero della Francesca, The Resurrection Piero della Francesca, The Resurrection

(self-portrait, detail of fresco), Museo Civico, Sansepolcro

|

|

Niccolò di Segna, Madonna col Bambino, 1336 circa, 102x67 cm, Museo Diocesano, Cortona

|

Madonna of the Misericordia

|

|

|

The painting of ‘Our Lady of Mercy’ in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena is attributed to Niccolò di Segna. It dates from around 1331 to 1332 and was destined for the church of San Bartolomeo in Vertine in Chianti. Niccolò’s picture may only come from his workshop however. Niccolò di Segna leased his workplace from the confraternity of the House of Santa Maria della Misericordia in Florence G55 . He made the panel probably for one of the altars of the House of Mercy. It shows a Lady of Mercy opening her cloak and sheltering under it male and female citizens of Tuscany. Judges, bishops, monks, devote women thus find protection under the tunic of the Virgin, under the deep blue maphorion. The citizens are painted smaller than the Virgin is, the painter thus expressed the concept that the citizens are less important than the Holy Virgin, a common way of representing the hierarchy of God’s family and mortals.[2]

|

Cuna

|

|

|

The Church of Santi Giacomo e Cristoforo is located nearby the great medieval building where once a 'grancia' (fortified farm) of Santa Maria della Scala Hospital was. The Church shows in the apse walls a little fresco cycle discovered in 1905 and now restored. The paintings are attributed to the third generation duccesque master Niccolò di Segna and show episodes from the life of Christ ('The Adoration of the Kings' and 'The Presentation to the Temple') and figures of Saints (Mary Magdalen, Agnes, Anne etc...)

|

Lucignano

|

|

|

The Virgin Enthroned and Child by Niccolò and his brother Francesco di Segna is a 14th century spire panel from the Church of St. Francis. The background, once gilded, has punching along the frame and all around the heads of the characters, to draw the halos.

In the lower right corner, there is the figure of a woman in prayer portrayed in reduced dimensions compared to the Virgin: this is the commissioner of the painting. The inscription that runs to the base of the throne reveals the identity of the woman 'Mrs Muccia who was wife of Guerrino Ciantari', a rich and pious widow, who donated the painting to the Church of San Francesco[3]. |

|

| |

|

Niccolò e Francesco di Segna, Madonna in trono col Bambino e committente, Museo Comunale, Lucignano

|

Piero della Francesca | The Resurrection, Museo Civico, Sansepolcro

[1] Source: Elisabetta Nardinocchi, ed. (2011). Guida al Museo Horne. Florence: Edizioni Polistampa.

[2] Niccolò di Segna was the son of Segna di Bonaventura, who had been himself a pupil of Duccio di Buoninsegna. The panel has the gentleness of a typical Sienese painting, but it is more austere and devoid of the rich ornamental gothic decorations we are used to of Sienese masters. Gold paint is lavishly applied however behind the Virgin. The Virgin is shown with much dignity, a pose enhanced by the long red robe kept together high by a simple girdle. The Virgin looks as sure of her status as the mother of a congregation, fully aware of her responsibilities, confident of her powers and defiant to any danger that might threaten the ones she has decided to protect.

The Madonna of the Misericordia is a very old theme, which disappeared almost completely after the fifteenth century. In Segna’s times already the image had become an icon, a symbol that was almost dogmatically copied in the same way as the Maestà’s of the thirteenth century. The theme is Byzantine. One of the last most famous relics of Constantinople was this blue maphorion of the Virgin. There exist early frescoes, Greek Orthodox icons and mosaics of the Virgin spreading her cloak like a veil over the citizens of Constantinople. The cloak was guarded preciously in the church of the Blachernae Palace of the city. It disappeared with the sack of the town in 1453 when the Osmanli Turks finally took, then pillaged the last city of the East Roman Empire. Greek priests and the Patriarch of Constantinople showed the tunic and carried it in procession through the town in times of hardships. This was also done in the last days of Constantinople G60 . Was it for this tunic that so many remained in the town when the Turks assaulted? Many defended the town to the last, confidant in the protection of the Holy Veil, in its inviolability and holy powers.

The Madonna of the Misericordia as a Byzantine symbol was taken up by Piero della Francesca. One of Piero’s first major paintings that we still have is the ‘Polyptych of the Misericordia’, dating from around 1445 to 1462 and now in the Museo Civico of Sansepolcro. The altarpiece shows a Madonna of the Misericordia very much like Niccolò di Segna’s picture. Piero had the citizens of Florence kneel under the Virgin, but the colours, the long red robe and the deep blue tunic with a girdle are all very much alike Niccolò’s painting. And the same Misericordia confraternity from which Niccolò di Segna hired his workshop ordered Piero’s panel G55 . Piero’s polyptych is grand. A Crucifixion panel stands above the Virgin and a predella shows scenes of Jesus’s passion. But the central panel that stood in the middle of the altar is a ‘Madonna of the Misericordia’. Panels of many saints, martyrs, evangelists, angels, and citizens flank Piero’s Madonna. This theme of the Madonna protecting saints or in the company of many saints is also a recurrent theme of Tuscan paintings.

The theme of the ‘Madonna della Misericordia’ evolved, not in the least in the pictures of Piero della Francesca himself. Piero would paint the same Virgin in the same colours many times over. He would place the figure in a wide robe, sometimes wide the more so while he presented a pregnant Mary, with the wideness of the robe that reminds of the open protective maphorion. Then he showed the Virgin under the open cloth of a tent, then with saints in a niche under a Roman arch, whereby the open tent and the niche could refer to the sheltering veil. The image remained in Piero’s mind. The image of a protective Virgin thus evolved to scenes in which the Virgin was still presented with a wide tunic but in which her sheltering role was hinted at by structures of the background. Other pictures showed Mary entirely enveloped in the wide blue maphorion, The ‘Madonna of the Misericordia’, Our Lady of Mercy, fell in disuse as an immediate theme in the fifteenth century. The tunic itself as the alleged relic also had disappeared with Christian Constantinople. After all, all the famous relics of the town however supposedly powerful had not been able to withhold the onslaught first of the Crusaders and then of the Turkish conquerors.

The image of a Holy Lady protecting figures under her robe was a universal image that can be found in other pictures than of Florentine and Byzantine origins. We refer for instance to a panel in Bruges made in the second half of the fifteenth century by Hans Memling. Memling was of German origin, born probably in a village near Mainz called Mommlingen. Memling worked in the Brussels shop of Rogier Van Der Weyden and he was influenced also by the Gent painter Hugo Van Der Goes. Most of Memling’s production dates from his stay in Bruges from 1466 to 1494 and no other painter is so dear to the hearts of the people of Bruges. Many of his panels have been preserved and are now in the Museum of the Hospital of Saint John in Bruges. Memling decorated with miniature scenes the shrine of the relics of Saint Ursula. One of the panels of the shrine shows a Saint Ursula holding a long arrow of her martyrdom but also covering under her open cloak the small figures of the eleven virgins that were martyred with her. We have no evidence that Memling travelled to Italy and such a voyage seems unlikely for the Bruges masterG9. But Memling worked for the Florentine merchant Tomaso Portinari who traded from out of Bruges. A painting of Memling was sent to the Sforzas of Milan. Another panel he made for the Florentine Jacopo Terri was even sent over sea to Florence. But the ship was captured and the picture landed in Danzig or Gdansk of Poland, another Hanza city G9. Also other portraits of Florentine merchants working in Bruges, made by the artist, prove that Memling had many connections with Italy. He may have seen drawings or even pictures of the Madonna della Misericordia. If not, the image of a protection offered by an open cloak around a saint was a symbolic gesture of protection that came to the mind independently and naturally in painters of the north as well as of Italy.

Niccolò di Segna ‘s painting was probably the centre panel of an altarpiece. The picture looks like the humble work of a local artisan, the kind of work that could be delivered by many craftsmen of Tuscany. However, Niccolò di Segna‘s picture does differ from the many naïve works of art of local artists. The Virgin is expressed in all her assurance. We see in Segna’s art one of the first very direct expressions of personality in an image of Mary, some of the first depictions of psychology in paintings. Niccolò di Segna emphasised in the Virgin’s face the inner power of the Madonna, all the pride of her protection and the awareness of the dignity of her position. Niccolò showed this all the more by the vertical austerity of his composition and the simplicity of his representation in which he avoided overloaded decoration and pomp. This mastery was the sign of a great artist. [Source: © René Dewil - The Art of Painting]

Art in Tuscany | Madonna della Misericordia | Madonna of Mercy

[3] Lucignano, Pearl of the Valdichiana | www.visitlucignano.it

|

|

|