Antonello da Messina (ca. 1430–1479) |

Antonello da Messina was one of the most groundbreaking and influential painters of the quattrocento. Born Antonello di Giovanni d'Antonio around 1430 in the seaport city of Messina, Sicily, his formation took place in Naples during the rule of Alfonso of Aragon, in a brilliant artistic climate open to French and Netherlandish painting. Antonello absorbed these influences, so much so that many of his near contemporaries believed he was the first to introduce the use of oil painting – already current in the North – in Italy. The 16th-century writer Vasari tells the life of Antonello da Messina as a tale of borrowings and transformations, the origin myth of oil painting. The fabled inventor of oil paint was Jan van Eyck, an alchemist as well as an artist according to Vasari, who discovered it after years of occult experimentation. He managed to keep his find a secret despite the distinctive smell of his paintings. Then Antonello, "a person of good and lively intelligence, of great sagacity", happened to go to Naples and see a van Eyck painting owned by King Alfonso. Antonello was so struck that he dropped everything and set out for Bruges, where he charmed the aged van Eyck with gifts until he shared the secret.[1] |

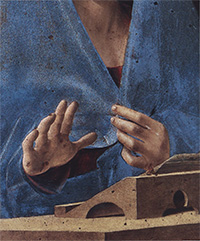

| The Virgin Annunciate is perhaps the most famous of the Sicilian painter's works and is one of the art icons of all time, dating back to Antonello's stay in Venice. The former enchants and surprises in its masterly orchestration of light sources, generating an interplay of backlight and, at the same time, wholly unifying the composition. But what is truly innovative is the interpretation of the Virgin Annunciate from Palermo, in which the painter achieves absolutely modern results, breaking up the traditional composition of the Annunciation scene. Here, indeed, Antonello condenses the sacred event into the single figure of the Virgin and concentrates on the personal and intimist aspect of the scene, underlining the psychological effects of the event revealed to the pensive and realistic figure of the Virgin and making the viewer feel, due to the absence of the angel, that he is the sole witness to the sacred event. The Virgin Annunciate was created for a domestic interior. It is a haunting image of the adolescent Mary when the angel Gabriel announces to her that she will bear God's Son. The modest Sicilian female, attired in a simple blue mantle, is aloof and mysterious. She is shown bust-length and against a plain background. Mary looks up from behind a reading desk upon which her book of devotions rests. Her direct outward gaze and right hand raised in a blessing gesture engage the viewer, who replaces Gabriel as the provider of the miraculous news and becomes an active participant in the charming painting's story. The lack of a pendant or adjoining panel suggests that the angel's presence is implied. Noteworthy in The Virgin Annunciate is Antonello's use of light to build convincing forms. To paint Mary's foreshortened right hand, he may have employed a velo, a stringed grid through which an artist observed objects and then recorded their contours onto a squared piece of paper. [2] The panel is a compelling depiction of Mary with an open devotional text on a simply rendered geometric lectern. She acknowledges the implied presence of the angel Gabriel, who is about to tell her that she will be the mother of the Son of God. In response to the angel's greeting, Mary clasps her blue cloak closed and holds it modestly in front of her chest. Meanwhile she gestures outwardly with her right hand extending beyond the picture plane's surface to Gabriel, who occupies the viewer's space. Some art historians feel that the foreshortened quality of the Virgin's right hand was achieved through the use of a velo (a string grid through which shapes were observed, drawn onto a squared piece of paper and then transferred to a painting). Although the subject is religious in nature, Antonello consciously chose a young and humble Sicilian girl for the model of the Blessed Virgin. In this way, he took a theme from the remote Biblical past and made it spiritually relevant, if not awe-inspiring, to anyone who saw the painting. |

||

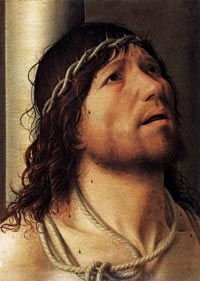

| The Christ at the Column from the Louvre constitutes the pinnacle of Antonello's explorations of this theme. The bold and highly original iconographic scheme conveys the sufferings of the martyred Christ in extreme close-up. Christ at the Column was intended for private devotion. The picture was painted late in Antonello's career - but whether in Venice or Sicily is not known.

|

||

| The expression Ecce Homo (Latin for "Behold the Man") comes from the New Testament Gospel According to John (19:5). They were the words spoken by Pontius Pilate when he presented Jesus Christ, scourged and wearing a crown of thorns, to the crowd who sought his crucifixion. The small size of this devotional panel suggests its portability desired by the original owner, who may have carried it during his travels in a special leather case. Antonello revisited the Ecce Homo theme repeatedly in his career. Christ Crowned with Thorns (possibly 1470) from The Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection has a profound impact on the viewer due to the immediacy of the painting's bust-length format inspired by similar Flemish works. A bare-chested Christ crowned with thorns is shown isolated behind a ledge. His facial features are in no way idealized or classically beautiful, emphasizing his humanity. And the expression of suffering on Jesus' anguished visage does not detract from the figure's sense of dignity. Despite certain abrasions to the panel's surface, Antonello's subtle modeling of Christ's nose and upper torso is still visible today. The New York Ecce Homo, dated 1470, shows the intense sentimentalism typical of the Flemish interpretation of the subject. There are four other versions of the subject by Antonello. One in the Galleria Alberoni, Piacenza, bears a date that is usually read as 1473. One formerly in the Ostrowski collection (disappeared from the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, during World War II) was dated 1474. Two others are in the Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Spinola, Genoa, and a private collection, New York (with a depiction of Saint Jerome in the Desert on the verso). Art in Tuscany | Antonello da Messina, Ecce Homo |

||

| In addition to religious painting, Antonello excelled in the art of secular portraiture to a degree that rivaled his Northern Italian contemporaries. Previously Italians had painted in tempera, their colours lacking the lucidity, depth and finesse that van Eyck and other northern Europeans achieved with oils. The earliest oil portraits relish the mimesis of the face that the new medium made possible. The mysterious and very famous Cefalù Portrait of a Man by Antonello, known for a long time as the Portrait of an Unknown Sailor - formerly in Lipari and used as the door of a pharmacy cupboard - who rivets the viewer's attention with his direct and ironic gaze, and enigmatic, inscrutable smile. His innovative portraits, with their superb descriptive powers and glimpses into the psychology of the sitter form part of a celebrated series of baruni or barons that Antonello painted from about 1470 until his death in 1479. In the oil on panel piece from Cefalù in Palermo, Italy, the artist's sharp visual insight into the sitter's personality is clear. Placed against a neutral background, Antonello portrayed the bust-length man in a three-quarter view common in the Netherlands. This allowed for a wider range of facial expressions and gave the viewer greater appreciation of the sitter's engaging glance, slightly mischievous smile and distinctly Sicilian features. Portrait of a Man draws the observer psychologically into the sitter's gaze. |

||

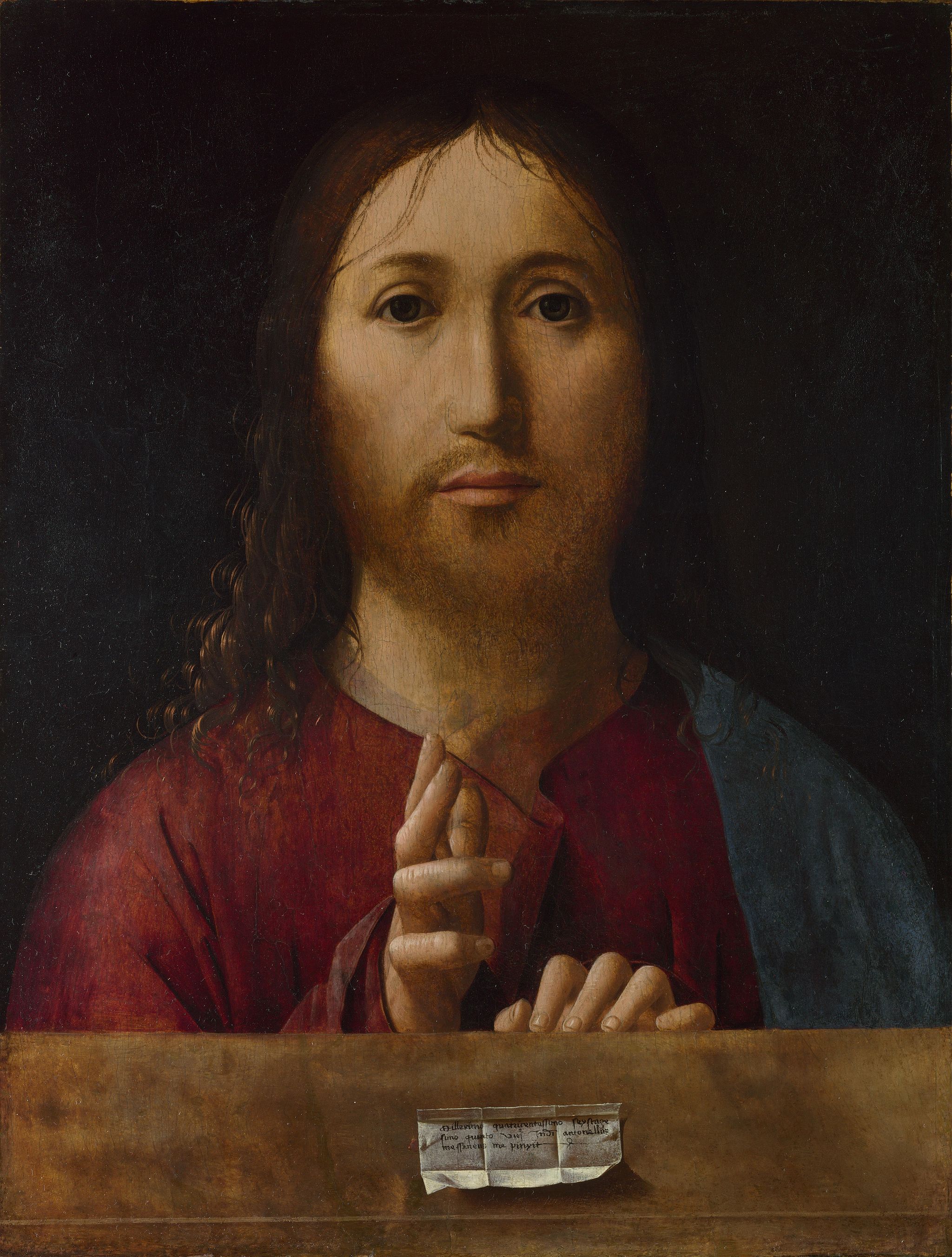

| This portrait is one of the best among the (more than ten) portraits painted by Antonello. It is assumed that it represents a military commander.

Antonello da Messina's male portraits differed from conventional medallion-style profile views by setting three-quarter bust portraits against a dark background and behind a parapet. The face in the Louvre painting is highly individual; no detail has escaped the artist's attention: the rings under the eyes, the scar on the upper lip, the tension in the jaw. The imperious gaze meets the spectator's, as if seeking to detain him. The technique of oil painting used here, which Antonello had learnt in the court of Naples, enabled him to render the subtlety of the reflections in the irises, the hairstyle with the thick fringe that catches the light, the precision of the shadows on the right wing of the nose, the right cheekbone, and the chin. The face emerges out of the dark background and the black garment highlighted by a simple white edging. |

||

| Tradition has it that when Antonello da Messina returned from Flanders he introduced the technique of oil painting to Venice. He was also influenced by northern painting in his Sicilan search for the individual character of people and things, as is evident from the extraordinary Portrait of a Man. His objective and incisive analysis of forms combines Piero della Francesca's stereometric achievements, Mantegna's use of perspective in his busts and venetian colour. Its present state or preservation shows that the highlighting on the red robe, has now become blackened by the lead base of the white pigment. www.galleriaborghese.it |

||

| This was said traditionally to be a self-portrait by Antonello, but there is no evidence of the man's identity. The light is held in the man's eyes, which are big, shiny orbs. This is not a Bruges merchant, but an Italian whose unshaven face is tough as well as pensive. This Renaissance man has more important things to think about than shaving, and his stubble is painted with realism, the pores just darkening. The hairs sticking out from his red cap are just as sharply real, contrasting with the rich, smooth skin tones, the finely sculpted and shadowed cheekbone. The behaviour of light - sinking into the flesh at some places, making his cheek red and brown, reflecting off his eyeballs and nose as it reflected on the water rippling in the Venetian lagoon - is painted here in a way that would have astonished the painting's first beholders. To them, the new art of oil painting was almost a magical practice, so convincingly did it simulate life. This painting might feel gimmicky in its naturalism, a demonstration work. But it has an emotional strength, a gravitas that gives its subject the look of an intellectual or a man involved with art and science. You can see why it was long identified as a self-portrait, because this man does not have the look of a noble. He's a bit hard, maybe quick to anger, maybe with a saturnine temperament. This man is a mysterious character, guarded, as if he doesn't quite trust us.

|

Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a man (1475 ca.), National Gallery, London |

|

|

||

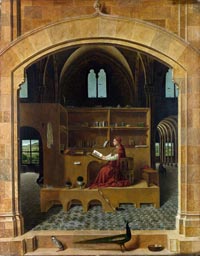

Antonello da Messina, Saint Jerome in his Study, about 1475, The National Gallery, Trafalgar Square, London

|

||

| The painting is recorded in a Venetian collection in 1529 as by Antonello, Van Eyck or Memling. Antonello may have painted it when in Venice in the 1470s. His style was much influenced by Netherlandish painting seen in the detailed treatment of objects such as the hanging towel and the view through the window. The 4th-century Saint Jerome was one of the four Fathers of the Church, and is often represented in the Renaissance. He was famous for the Vulgate — the translation of the Bible into Latin — and is often depicted in his study. A painting of Saint Jerome, thought to be by Jan van Eyck, is known to have been in Naples in 1456 and Antonello may have seen it. He certainly worked in Naples as well as his native Sicily. Saint Jerome in his Study is one of the most famous of the artist's mature works. The painting which Marcantonio Michiel - a cultivated art connoisseur - saw in 1529 in the house of a rich merchant Antonio Pasqualigo, clearly shows why the Venetian aristocrats competed to acquire Antonello's portraits and small devotional paintings as soon as the artist from Messina set foot in Venice. The ingenious architectural setting in this picture must immediately have appeared an unprecedented novelty to everyone, with Jerome's study inserted into a powerful, dark church, rather like a set of Chinese boxes, backlit from windows opening onto an airy rural landscape. The Saint Jerome, with its silent luminosity, its minute descriptive detail, the highly skilful syntax of perspective obtained through the light that makes everything clear and limpid, must have been admired as an absolute masterpiece, on a par with the great Flemish painters such as van Eyck or Memling, to whom it has sometimes been attributed. Art in Italy | Antonello da Messina, Saint Jerome in his Study |

||

| Antonello da Messina arrived in Venice in the winter of 1474-75, staying there until the autumn of 1476. Venetian documents record his presence in the city and his relations with the nobleman Pietro Buon, who commissioned from him the large altarpiece for San Cassiano (parts of which are now in the Vienna Kunsthistorishes Museum). The Pietà is the only work left in Venice to bear witness to the artist’s presence in the city. It is also interesting to note that though the subject of the Pietà was frequently explored by Mantegna and Bellini, this is the only known version of the theme painted by Antonello da Messina. The Pietà with three angel was probably painted at the beginning of his stay in the city. The splendid background scene, one of the best preserved parts of this very badly damaged painting, with the apse of the church of San Francesco d'Assisi in Messina, is the artist's tribute to the city of his birth, Messina. The Museo Correr is Venice's civic museum, dedicated to the history of the Republic. Based on the private collection of Venetian nobleman Teodoro Correr (1750-1830), it is elevated beyond mere curiosity value by the second-floor gallery, which is essential viewing for anyone interested in early Renaissance Venetian painting. |

||

|

||

Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a Man, 1474, oil on panel, Berlin, Staatliche Museen |

||

| This work was signed by Antonello, and has been considered his very last work if the date on it is interpreted as 1478. It is therefore his last male portrait, and it housed in the Staatliche Museen (Gemäldegalerie) of Berlin, Germany.

Relevant is the insertion by Antonello of a landscape in the background, as other artists (including Giovanni Bellini) used this innovative feature only starting from the 1490s. The picture shows influences from the late Flemish paintings, as can be seen from the rendering of the dress, similar to a Van Eyck portrait now at Sibiu.

The San Cassiano Altarpiece |

|

|

| The San Cassiano Altarpiece and the Saint Sebastian from Dresden are all that remain of Antonello’s work for the Venetian churches. In August, Antonello begins working on the San Cassiano Altarpiece, fragments of which are held by the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. It is commissioned by the aristocrat Pietro Bon in Venice. 'The monumental fragment of what is known as the Pala di San Cassiano by Antonello da Messina, who originated from Sicily. Even in its fragmentary state the first manifestation of this type of altar and the importance of the Pala which attracted a school of followers can still be appreciated, and Antonello's interest in the material appearance of the surface resulting from his contact with Early Netherlandish painting in association with a downright cubic corporeality can be admired.'[5] Art in Italy | Antonello da Messina | San Cassiano Altarpiece

Group of figures in a square, Musée du Louvre, Paris |

San Cassiano Altarpiece, 1475–76, Kunsthistoriches Museum, Vienna |

|

| Purchased in 1983, this drawing was recognized as the work of Antonello da Messina the following year. Antonello da Messina's contact with Northern European art during his apprenticeship in Naples in the 1440s and 1450s had a profound influence on his style. Several features of this drawing—in particular, the elongated proportions of the figures and the heavy drapery arranged in sharp, angular folds—demonstrate Antonello's absorption of Flemish and Burgundian art. This drawing demonstrates 'a Northern influence in the treatment of figures and drapery, which reveals a familiarity with the work of Petrus Christus and Jean Fouquet, while the depiction of a moment of everyday life also suggests familiarity with the art of Northern Europe. Antonello's skill, however, allows him to combine these influences with the tradition of his own cultural milieu, expressed in the execution of the houses, rendered in Italian Renaissance perspective'.[6] Antonello da Messina | Group of Draped Figures

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

More images of Antonello da Messina

|

||||

| Giorgio Vasari, the 16th-century biographer, said that Antonello da Messina learned oil painting from Jan van Eyck, whom he had visited in Flanders. This is improbable as Jan van Eyck died when Antonello was 11 years old. Nevertheless, critics have continued to postulate a visit to Flanders to explain the Flemish qualities in Antonello's art as well as his mastery of oil painting. A different viewpoint, which has evolved recently, sees his apprenticeship to the painter Colantonio in Naples and his contact with Petrus Christus, a Flemish follower of Jan van Eyck, as the crucial factors in Antonello's early development.

|

Crucifixion (detail), 1475, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

The Dresden St. Sebastian is a late work of Antonello showing Venetian influences. Antonello's Saint Sebastian is an appealing picture which offers a wide range of visual stimuli. Seemingly oblivious to the arrows which pierce his body, the young Saint Sebastian is tethered to a tree, partially nude and in discreet contrapposto. The vanishing point is low on the horizon, so that the recession into space is sudden, if not dramatic, emphasized by the foreshortened column fragment in the right foreground. |

|||

|

||||

Vasari Corridor, Florence |

Panorama Sant’Angelo in Colle, Montalcino | Florence, Duomo

|

||

Art in Tuscany | Male portraits by Antonello da Messina (1430–1479) Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists | Antonello da Messina Antonello da Messina | L'Annunciazione della chiesa di Santa Maria Annunziata di Palazzolo Acreide, 1474 Art in Tuscany | Italian Renaissance painting Antonello da Messina | www.mostraantonellodamessina.it/en| Download the Exhibition Guide in English [PDF - 1.4Mb] Barbera, Gioacchino, Andrea Bayer and Keith Christiansen, Antonello da Messina: Sicily's Renaissance Master (exh. cat.), New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005. The Museo Correr | Pinacoteca |

||||

| This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain, and uses material from the Wikipedia article Antonello da Messina published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, December |

Cypress trees between San Quirico d'Orcia and Montalcino |

||

|

||||

Montefalco |

Sansepolcro |

|||

|

||||

Crete Senesi, surroundings of Podere Santa Pia |

||||

| Podere Santa Pia is situated in the unspoiled valley of the Ombrone River, only 21 kilometres from Montalcino. This valley is famous locally as being of great natural beauty and still very undeveloped. |

||||