| |

|

Donatello (Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi; c. 1386 – December 13, 1466) was a famous early Renaissance Italian artist and sculptor from Florence. He is, in part, known for his work in bas-relief, a form of shallow relief sculpture that, in Donatello's case, incorporated significant 15th century developments in perspectival illusionism.

A good deal is known about Donatello's life and career, but little is known about his character and personality, and what is known is not wholly reliable. He never married and he seems to have been a man of simple tastes. Patrons often found him hard to deal with in a day when artists' working conditions were regulated by guild rules. Donatello seemingly demanded a measure of artistic freedom. Although he knew a number of Humanists well, the artist was not a cultured intellectual. His Humanist friends attest that he was a connoisseur of ancient art. The inscriptions and signatures on his works are among the earliest examples of the revival of classical Roman lettering. He had a more detailed and wide-ranging knowledge of ancient sculpture than any other artist of his day. His work was inspired by ancient visual examples, which he often daringly transformed. Though he was traditionally viewed as essentially a realist, later research indicates he was much more.

Donatello (diminutive of Donato) was the son of Niccolò di Betto Bardi, a Florentine wool carder. It is not known how he began his career, but it seems likely that he learned stone carving from one of the sculptors working for the cathedral of Florence about 1400. Some time between 1404 and 1407 he became a member of the workshop of Lorenzo Ghiberti, a sculptor in bronze who in 1402 had won the competition for the doors of the Florentine baptistery. Donatello's earliest work of which there is certain knowledge, a marble statue of David, shows an artistic debt to Ghiberti, who was then the leading Florentine exponent of International Gothic, a style of graceful, softly curved lines strongly influenced by northern European art. The David, originally intended for the cathedral, was moved in 1416 to the Palazzo Vecchio, the city hall, where it long stood as a civic-patriotic symbol, although from the 16th century on it was eclipsed by the gigantic David of Michelangelo, which served the same purpose. Other of Donatello's early works, still partly Gothic in style, are the impressive seated marble figure of St John the Evangelist for the cathedral façade and a wooden crucifix in the church of Santa Croce. The latter, according to an unproved anecdote, was made in friendly competition with Brunelleschi, a sculptor and an architect. |

|

Donatello's statue outside of the Uffizi Galleria Donatello's statue outside of the Uffizi Galleria |

| |

|

|

The full power of Donatello first appeared in two marble statues, St Mark and St George (both completed c. 1415), for niches on the exterior of Or San Michele, the church of Florentine guilds (St George has been replaced by a copy; the original is now in the Bargello). Here, for the first time since classical antiquity and in striking contrast to medieval art, the human body is rendered as a self-activating, functional organism, and the human personality is shown with a confidence in its own worth. The same qualities came increasingly to the fore in a series of five prophet statues that Donatello did beginning in 1416 for the niches of the campanile, the bell tower of the cathedral (all these figures, together with others by lesser masters, were later removed to the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo). The statues were of a beardless and a bearded prophet, as well as a group of Abraham and Isaac (1416-21) for the eastern niches; the so-called Zuccone ("pumpkin," because of its bald head); and Jeremiah for the western niches.

The Zuccone is deservedly famous as the finest of the campanile statues and one of the artist's masterpieces. In both the Zuccone and the Jeremiah (1427-35), their whole appearance, especially highly individual features inspired by ancient Roman portrait busts, suggests classical orators of singular expressive force. The statues are so different from the traditional images of Old Testament prophets that by the end of the 15th century they could be mistaken for portrait statues.

A pictorial tendency in sculpture had begun with Ghiberti's narrative relief panels for the north door of the baptistery, in which he extended the apparent depth of the scene by placing boldly rounded foreground figures against more delicately modeled settings of landscape and architecture. Donatello invented his own bold new mode of relief in his marble panel St. George Killing the Dragon (1416-17, base of the St. George niche at Or San Michele). Known as schiacciato ("flattened out"), the technique involved extremely shallow carving throughout, which created a far more striking effect of atmospheric space than before. The sculptor no longer modeled his shapes in the usual way but rather seemed to "paint" them with his chisel. A blind man could "read" a Ghiberti relief with his fingertips; a schiacciato panel depends on visual rather than tactile perceptions and thus must be seen.

Donatello continued to explore the possibilities of the new technique in his marble reliefs of the 1420s and early 1430s. The most highly developed of these are The Ascension, with Christ Giving the Keys to St Peter, which is so delicately carved that its full beauty can be seen only in a strongly raking light; and the Feast of Herod (1433-35), with its perspective background. The large stucco roundels with scenes from the life of St John the Evangelist (about 1434-37), below the dome of the old sacristy of San Lorenzo, Florence, show the same technique but with colour added for better legibility at a distance.

Meanwhile, Donatello had also become a major sculptor in bronze. His earliest such work was the more than life-size statue of St Louis of Toulouse (c. 1413) for a niche at Or San Michele (replaced half a century later by Verrocchio's bronze group of Christ and the doubting Thomas). Toward 1460 the St. Louis was transferred to Santa Croce and is now in the museum attached to the church. Early scholars had an unfavourable opinion of St Louis, but later opinion held it to be an achievement of the first rank, both technically and artistically. The garments completely hide the body of the figure, but Donatello successfully conveyed the impression of harmonious organic structure beneath the drapery. Donatello had been commissioned to do not only the statue but the niche and its framework. The niche is the earliest to display Filippo Brunelleschi's new Renaissance architectural style without residual Gothic forms. Donatello could hardly have designed it alone; Michelozzo, a sculptor and architect with whom he entered into a limited partnership a year or two later, may have assisted him. In the partnership, Donatello contributed only the sculptural centre for the fine bronze effigy on the tomb of the schismatic pope John XXIII in the baptistery; the relief of the Assumption of the Virgin on the Brancacci tomb in Sant'Angelo a Nilo, Naples; and the balustrade reliefs of dancing angels on the outdoor pulpit of Prato Cathedral (1433-38). Michelozzo was responsible for the architectural framework and the decorative sculpture. The architecture of these partnership projects resembles that of Brunelleschi and differs sharply from that of comparable works done by Donatello alone in the 1430s. All of his work done alone shows an unorthodox ornamental vocabulary drawn from both classical and medieval sources and an un-Brunelleschian tendency to blur the distinction between the architectural and the sculptural elements. Both the Annunciation tabernacle in Santa Croce and the Cantoria (the singer's pulpit) in the Duomo (now in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo) show a vastly increased repertory of forms derived from ancient art, the harvest of Donatello's long stay in Rome (1430-33). His departure from the standards of Brunelleschi produced an estrangement between the two old friends that was never repaired. Brunelleschi even composed epigrams against Donatello.

|

|

Statue of Habacuc, better known as "Zuccone" ("pumpkin"). From the bell tower of the Duomo of Florence, Italy. Marble. |

|

Donatello, David, about 1440s, bronze, height: 158 cm, Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargelo

|

| |

|

|

During his partnership with Michelozzo, Donatello carried out independent commissions of pure sculpture, including several works of bronze for the baptismal font of San Giovanni in Siena. The earliest and most important of these was the Feast of Herod (1423-27), an intensely dramatic relief with an architectural background that first displayed Donatello's command of scientific linear perspective, which Brunelleschi had invented only a few years earlier. To the Siena font Donatello also contributed two statuettes of Virtues, austerely beautiful figures whose style points toward the Virgin and angel of the Santa Croce Annunciation, and three nude putti, or child angels (one of which was stolen and is now in the Berlin museum). These putti, evidently influenced by Etruscan bronze figurines, prepared the way for the bronze David, the first large-scale, free-standing nude statue of the Renaissance. Well-proportioned and superbly poised, it was conceived independently of any architectural setting. Its harmonious calm makes it the most classical of Donatello's works. The statue was undoubtedly done for a private patron, but his identity is in doubt. Its recorded history begins with the wedding of Lorenzo the Magnificent in 1469, when it occupied the centre of the courtyard of the Medici palace in Florence. After the expulsion of the Medici in 1496, the statue was placed in the courtyard of the Palazzo Vecchio.

Donatello was commissioned to make a marble statue of David, victorious after his battle with Goliath, twice in his career. Donatello was first commissioned to carve a statue of David in 1408. The commission came from the operai of the cathedral of Florence, who intended to decorate the buttresses of the tribunes of the cathedral with 12 statues of prophets. The marble David is Donatello's earliest known important commission, and it is a work closely tied to tradition, giving few signs of the innovative approach to representation that the artist would develop as he matured.

Whether the bronze David was commissioned by the Medici or not, Donatello worked for them (1433-43), producing sculptural decoration for the old sacristy in San Lorenzo, the Medici church. Works there included 10 large reliefs in coloured stucco and two sets of small bronze doors, which showed paired saints and apostles disputing with each other in vivid and even violent fashion.

In 1443, when Donatello was about to start work on two much more ambitious pairs of bronze doors for the sacristies of the cathedral, he was lured to Padua by a commission for a bronze equestrian statue of a famous Venetian condottiere, Erasmo da Narmi, popularly called Gattamelata (The Honeyed Cat), who had died shortly before. Such a project was unprecedented - indeed, scandalous - for since the days of the Roman Empire bronze equestrian monuments had been the sole prerogative of rulers. The execution of the monument was plagued by delays. Donatello did most of the work between 1447 and 1450, yet the statue was not placed on its pedestal until 1453. It portrays Gattamelata in pseudo-classical armour calmly astride his mount, the baton of command in his raised right hand. The head is an idealized portrait with intellectual power and Roman nobility. This statue was the ancestor of all the equestrian monuments erected since. Its fame, enhanced by the controversy, spread far and wide. Even before it was on public view, the king of Naples wanted Donatello to do the same kind of equestrian statue for him.[2]

In the early 1450s, Donatello undertook some important works for the Paduan Church of San Antonio: a splendidly expressive bronze crucifix and a new high altar, the most ambitious of its kind, unequaled in 15th-century Europe. Its richly decorated architectural framework of marble and limestone contains seven life-size bronze statues, 21 bronze reliefs of various sizes, and a large limestone relief, Entombment of Christ. The housing was destroyed a century later, and the present arrangement, dating from 1895, is wrong both aesthetically and historically. The majestic Madonna, with an austere frontal pose seemingly a conscious reference to an earlier venerated image, and the delicate, sensitive St Francis are particularly noteworthy. The finest of the reliefs are the four miracles of St Anthony, wonderfully rhythmic compositions of great narrative power. Donatello's mastery in handling large numbers of figures (one relief has more than 100) anticipates the compositional principles of the High Renaissance.

Donatello was apparently inactive during the last three years at Padua, the work for the San Antonio altar unpaid for and the Gattamelata monument not placed until 1453. He had dismissed the large force of sculptors and stone masons used on these projects. Offers of other commissions reached him from Mantua, Modena, Ferrara, and even perhaps from Naples, but nothing came of them. Clearly, Donatello was passing through a crisis that prevented him from working. He was later quoted as saying that he almost died "among those frogs in Padua." In 1456 the Florentine physician Giovanni Chellini noted in his account book that he had successfully treated the master for a protracted illness. Donatello completed only two works between 1450 and 1455: the wooden statue St John the Baptist in Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice, shortly before his return to Florence; and an even more extraordinary figure of Mary Magdalen in the Florentine baptistery. Both works show new insight into psychological reality; Donatello's formerly powerful bodies have become withered and spidery, overwhelmed, as it were, by emotional tensions within. When the Magdalen was damaged in the 1966 flood at Florence, restoration work revealed the original painted surface, including realistic flesh tones and golden highlights throughout the saint's hair.

During Donatello's absence, a new generation of sculptors who excelled in the sensuous treatment of marble surfaces had arisen in Florence. Thus Donatello's wooden figures must have been a shock. With the change in Florentine taste, all of Donatello's important commissions came from outside Florence. They included the dramatic bronze group Judith and Holofernes (later acquired by the Medici and now standing before the Palazzo Vecchio) and a bronze statue of St John the Baptist for Siena Cathedral, for which he also undertook in the late 1450s a pair of bronze doors. This ambitious project, which might have rivaled Ghiberti's doors for the Florentine baptistery, was abandoned about 1460 for unknown reasons (most likely technical or financial). Only two reliefs for them were executed; one of them is probably the Lamentation panel now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The last years of Donatello's life were spent designing twin bronze pulpits for San Lorenzo, and, thus, again in the service of his old patrons the Medici, he died. Covered with reliefs showing the passion of Christ, the pulpits are works of tremendous spiritual depth and complexity, even though some parts were left unfinished and had to be completed by lesser artists.

|

|

|

Donatello's slightly smaller than life-sized bronze David was most likely commissioned by Cosimo de' Medici and it stood on a column in the courtyard of the Medici palace in Florence. The sleekly sensual depiction of the adolescent David, who stands in a languid pose, his left foot carelessly resting on Goliath's severed head, is remarkable for its naturalism. Donatello departed, however, from familiar images of David by presenting him nude, in the manner of a classical ephebe or slim, pre-pubescent boy. The unusual representation of the David, departing as it does from the biblical text and from classical forms of heroism, suggest that Donatello intended to convey more than just the narrative of David and Goliath. This lead to recent interpretations of the figure's purported androgyny, his sexuality and his homoerotic charge.

David has placed one foot on the severed head of Goliathin a positively playful manner. and is almost casually pressing it against the cushion he is standing on. The magnificendy decorated helmet and his beard cover large sections of his face. though the supposed superiority of the now defeated man is still visible in it. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Prato Cathedral, outside pulpit by Donatello and Michelozzo

|

The Pulpit for the exterior facade of the Cathedral in Prato, begun in 1428 and after long pauses finished ten years later, was executed by Donatello together with Pagno di Lapo and Michelozzo. Donatello was responsible for the architecture and the putti, whose joyous movements suggest a vital force that was to reach its zenith in the Cantoria for the Cathedral of Florence. Presently displayed in the Museum of the Opera del Duomo of Prato, it has been replaced on the outside with a copy. |

|

Donatello, Pulpito per l’ostensione della Sacra Cintola - Prato, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo

|

Siena

|

|

|

|

Donatello, Feast of Herod, 1423-1427, gilded bronze, 60 x 60 cm, Siena, Baptistery di San Giovanni, part of baptismal font

|

In 1423, Donatello received one of his first important commissions from outside Florence. He was asked to contribute to the work on the font in the Siena Baptistery, comprising a relief showing Herod's Banquet. A total of six reliefs by different artists, including Lorenzo Ghiberti and Jacopo della Quercia, were to decorate the font. Donatello's reliefs extremely effective. He demonstrates a masterly ability co draw his spectators into the events being portrayed. The border of the relief is extremely simple and acts as a passe-partout. There is nothing else separating the observer from the scene depicted, which is seen as if through a window. At first glance there is an impression of a perfect illusion of spatial depth. The scene aligned to a central vanishing point, and includes several masterly examples of foreshortening.

DonateIlo even took into account that the observer would be looking at the relief from above. When looked at more closely, however, one can detect a number of breaks that are subtly incorporated into the illusion of reality. One of the first things that one notices in this respect is that DonateIlo has depicted several events that occurred in succession as happening at the same time. In the background we can see a soldier bearing the head of John the Baptist, which is simultaneously being presented to Herod, who is shrinking back in shock, at the front. A musician in the central area of the relief is a reference to the dance of Salome, which she used co beguile her stepfather into having the Baptist killed. Despite the arrangement of the space along central perspective lines, the relief differs noticeably from the centralized composition typical of the Renaissance.

Donatello's relief, Herod's Banquet, appears to have found favour with his clients, because immediately afterwards he was commissioned to produce two bronze figures for the font, Faith, (La Fede), and Hope (La Speranza).

|

The cathedral's valuable pieces of art including The Feast of Herod by Donatello, and works by Bernini and the young Michelangelo make it an extraordinary museum of Italian sculpture.

The main attraction of the baptistry [1] is the hexagonal baptismal font, containing sculptures by Donatello, Jacopo della Quercia and others. The panel of The Feast of Herod is one of the great masterpieces of Renaissance sculpture. It was the first relief to be built in accordance with the rules of perspective.

The relief of Herod's Feast, at Siena, was executed by Donatello in 1425-1427. It is one of two panels originally ordered from Jacopo della Quercia for the baptismal fonts of Siena Cathedral. Here the architectural setting acts as one of the principal motifs of the scene. Possibly this setting was designed by Michelozzo. At any event it stands out in the history of art as the first relief to be built up in accordance with the rules of perspective. (...) This strict perspective layout and the network of straight lines structuring it, heighten the dramatic effect of the scene. Starting from the Baptist's severed head presented on a salver to the horrified Herod, arises the crescendo of rhythmed gestures conveying the emotional response of the figures, expressed already by contorted or spirited movements, by the restless animation of the drapery. The upsweep of her dress shows us Salome still dancing. The memory of her slender, buoyant figure lingers on in Lippi and Botticelli.[6]

|

|

|

|

|

In 1427 Donatello executed the Herod's Banquet, a bronze relief, for the Baptismal Font in the Cathedral of Siena. He also executed two small statues of Faith and Hope.

Donatello creates an intensely dramatic atmosphere in a very shallow space, due to his masterful use of a flat perspectival relief that he called “stiacciato” (the Tuscan word for “flattened”). The figures in the foreground, energetically modeled in high relief, are in the grips of deep emotion at the tragic sight of John the Baptist’s head being brought in on a platter, while the figures in the background, rendered in very shallow relief, go calmly on with what they were doing.

The two small statues on the corners, representing Faith and Hope, were made by Donatello in 1429. The gentle, beautiful faces of these two figures communicate a deep spirituality, and their slender bodies and elegant draperies are very finely modeled. These statues show a lyrical grace that is different from the relief of the Herod's Banquet, suggesting that his temporary collaboration with Ghiberti on the decoration of the Font may have caused Donatello to return to earlier methods of expression that had long been abandoned.

Of the six figures of the Virtues that were commissioned for the Sienese font, including ones from Giovanni di Turino and Goro di ser Neroccio, Donatello created those of Faith (La Fede) and Hope (La Speranza). Both figures

are positively moving out of the tabernacles in an extreme sideways turning.

Here, Faith is personified by a woman who is dressed in a voluminous garment and in her left hand is holding the cup which, in the Eucharist, symbolizes the forgiveness of sins.

Hope was traditionally embodied in the form of a women who is raising both hands and gazing upwards, towards God. Donatello omitted all other attributes in his sculpture.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

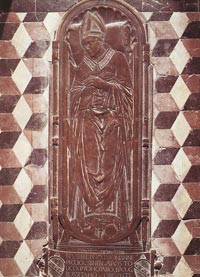

In the works that followed the statues in the Baptistry of Siena - the Tombstone of Bishop Giovanni Pecci in the Cathedral of Siena, signed and dated 1426, the Assumption of the Virgin carved in Pisa in 1427 for the Brancacci tomb in Sant'Angelo a Nilo (Naples), the Christ Giving the Keys to St Peter of the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Pazzi Madonna of the Berlin Museum - Donatello returned to the flattened relief, pushing its expressive possibilities to the utmost limits.

According to the inscription, Giovanni Pecci, the bishop of Grosseto, died on 1 March 1426. The commission to design the bronze tombstone was presumably given to Donatello immediately afterwards. The perspective of the arrangement is such that the dead man does not –as one might expect– appear to be resting for eternity, but to be lying on a stretcher whose lower handles are still! visible. Given Donatello's constant reformulation of and innovative changes to traditional artistic means of composition. the Pecci tombstone is another sign of his restless temperament.[1] |

|

|

Saint John the Baptist (1547)

|

|

|

Saint John the Baptist (1547) This is a late work, made in Florence in 1457 and brought to Siena once it was finished. It is very similar in style and feeling to the Mary Magdalene now in the Opera del Duomo museum in Florence. The thin figure of Saint John exudes drama with his haggard face, sunken eyes, protruding veins, and bristly hair and beard. His half-open mouth and stunned, fixed stare give evidence of his deep suffering. |

|

|

|

|

|

Tondo of the Virgin and Child (1457) This tondo was originally over the door to the Chapel of Pardon, which was moved to another position around 1660 when work began on Bernini’s Chapel of Votive Offerings. The sacred image was made by Donatello toward the end of his life as a sculptor (1457) and shows the Virgin and Child with three cherubs in a round frame specifically designed for viewing from below, as revealed by the foreshortening of the figures and the space behind them. The sweet, melancholy face of the Virgin Mary seems to foresee the fate awaiting her Child. Atender note is struck by the very natural gesture of the Baby Jesus as he slips his hand under his mother’s veil to touch her bare skin. The stiff, schematic rendering of the cherubs behind the main figures indicates a later addition by another artist. |

|

|

| |

[1] The Battistero di San Giovanni is located in the square with the same name, near the final spans of the choir of the Siena's cathedral, the Duomo.

The baptistry was built between 1316 and 1325 by Camaino di Crescentino, the father of Tino di Camaino. The façade, in Gothic style, is unfinished in the upper part, such as the apse of the cathedral. In the interior, the rectangular hall, divided into a nave and two aisles by two columns, contains a hexagonal baptismal font in bronze, marble and vitreous enamel, realized in 1417-1431 by the main sculptors of the time: Donatello (panel of "Herod's Banquet" and statues of the "Faith" and "Hope"), Lorenzo Ghiberti, Giovanni di Turino, Goro di Neroccio and Jacopo della Quercia (statue of John the Baptist and other figures). The panels represent the Life of John the Baptist, and include:

* "Annunciation to Zacharias" by Jacopo della Quercia (1428-1429)

* "Birth of John the Baptist" by Giovanni di Turino (1427)

* "Baptist Preaching" by Giovanni di Turino (1427)

* "Baptism of Christ" by Ghiberti (1427)

* "Arrest of John the Baptist" by Ghiberti and Giuliano di Ser Andrea

* "Herod's Banquet" by Donatello (1427)

These panels are flanked on the corners by six figures, two by Donatello ("Faith" and "Hope") in 1429; three by Giovanni di Turino ("Justice", "Charity" and "Providence", 1431); and the "Fortitude" is by Goro di Ser Neroccio (1431).

The marble shrine on the font was designed by Jacopo della Quercia between 1427 and 1429. The five "Prophets" in the niches and the marble statuette of "John the Baptist" at the top are equally by his hand. Two of the bronze angels are by Donatello, three by Giovanni di Turino (the sixth is by an unknown artist).

The frescoes are by Vecchietta and his school (1447-1450, Articles of Faith, Prophets and Sibyls), Benvenuto di Giovanni, the school of Jacopo della Quercia e, perhaps, one by Piero Orioli. Vecchietta also painted two scenes on the wall of the apse, representing the Flagellation and the Road to Calvary. Michele di Matteo da Bologna painted in 1477 the frescoes on the vault of the apse.

[2] The bronze David was probably Donatello's most untypical1 and at the same time his most popular work . Rarely have the various attempts at dating the work diverged so considerably over many years of research.

1427 has been given' as the earliest, and 1460 as the latest date of its creation. Nowadays this sculpture, as puzzling as it is fascinating, is generally believed to date from around 1440. There is proof that the David, which is now in the Bargello, was erected in the interior courtyard of the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in 1469, and then moved to the Palazzo Vecchio after the Medicis were expelled in 1495. These early locations for the David provide obvious parallels with Donatello's later Judith and Holofernes group. There have been repeated suggestions of a possible link between the two works that, despite their considerable stylistic differences, were even considered to be counterparts. However, the only indisputable assumption is that an inherent part of both sculptures was a political symbolism that is difficult to decipher today. David was undoubtedly well suited to be a symbol of the Florentines' liberal view of themselves, and had in this sense been raised almost m the level of state symbol.

Donatello's David once more demonstrates to us bis admiration of classical sculpture. This is communicated in the balanced distribution of weight in the figure and its unusual nudity. These similarities to classical sculpture apart, however, the figure is ahead of its time. The appearance of the body is so close to nature that even Vasari was led to wonder whether the figure 'was not moulded on the living form.' The youthful body is flawlessly beautiful. The earliest free-standing nude of the post-classical era, it is also impressively graceful when seen from the side. His profile, with the laurel wreath on his helmet, could scarcely be more striking.

Rolf C. Wirtz, Donatello (Masters of Italian Art Series), Konemann, 1998, p. 69.

The National Bargello Museum | The National Bargello Museum is housed in the former Palace of the Capitain of the People. According to Vasari, the original core, dating to 1255, was built following a design by a certain Lapo, father of Arnolfo di Cambio, and corresponds to the site overlooking Via del Proconsolo: this was the city's oldest seat of government.

From the late 13th century until 1502 the Palace was the official residence of the Podestà, the magistrate who governed the city and who, by tradition, had to come from another town. Around 1287 the balcony was built, a beautiful loggia overlooking the courtyard where the Podestà often held meetings with the representatives of the guilds and corporations. The tower, which predates the rest of the building, held a bell known as La Montanina, which rang to call the Florentine citizens to gather in case of war or siege.

In 1502 the palace became the headquarters of the Council of Justice and of the Police, whose head was known as the Bargello. In 1786, when the grand duke Pietro Leopoldo abolished the death penalty, the torture instruments were burnt in the courtyard. The prisons remained in use until 1857, when they were transferred to the former Murate convent; the palace underwent complete restoration after this date under the guidance of the architect, Francesco Mazzei.

The Bargello became a sculpture museum in 1886, the year in which the fifth centenary of Donatello's birth was celebrated. Two years later, the museum received a generous gift of Gothic and Renaissance artifacts from the French antiquarian, Louis Carrand, followed, in 1894, by a donation made by Costantino Ressman, ambassador and collector of weapons. In 1907, Giulio Franchetti donated his collection of fabrics with examples dating from the 6th to 18th centuries.

On display in the Michelangelo Room are works by that great Renaissance artist: the so-called Drunken Bacchus, sculpted in Rome between 1497 and 1499; the marble tondo with the Madonna and Child with St John, carried out in 1504 for Bartolomeo Pitti; the David-Apollo, marble statue, begun in 1531; the Brutus, marble bust carried out around 1540; as well as the Bacchus, marble statue, sculpted by Jacopo Sansovino around 1520, the bronze bust of Cosimo I by Benvenuto Cellini; also on display another outstanding example of 16th-century sculpture, Giambologna's splendid Mercury, a bronze from 1564. On display in the cabinet are a number of beautiful bronze animals made by the same artist around 1567 for the Medici villa in Castello.

In 1886, the huge room that was the former Great Council Chamber was used to display the works of Donatello and of other Florentine Renaissance sculptors: among the works of the maestro were the David, a beautiful bronze carried out for Cosimo the Elder around 1430; a marble David, considered one of his early works; the Marzocco, the symbol of the city of Florence; the Bust of a Youth and the Bust of Niccolò da Uzzano.

Also on display in this room are two panels depicting the Sacrifice of Isaac made by Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi for the competition for the second bronze door of the Baptistery. The Bargello's majolica collection owes much to the Medici's passion for collecting, in particular that of Cosimo I, who particularly appreciated the art of ceramics and porcelain-making. Thanks to many gifts, also by modern collectors, the room offers a practically complete panorama of the history of Italian majolica: extremely rare 15th-century pieces from the Cafaggiolo and Deruta workshops, and, from the 16th century, important examples of Urbino and Faenza majolica, as well as splendid examples of Venice majolica also covering the following century.

Two whole rooms are dedicated to the glazed terracotta works by Giovanni and Andrea della Robbia, among which we should mention the Nativity, belonging to Giovanni's mature period, the Noli me tangere, made by Giovan Francesco Rustici and glazed by Giovanni and, among Andrea's works, a Bust-portrait of a Youth, possibly Pietro di Lorenzo de' Medici.

Since 1873, the Verrocchio Room has housed Tuscan works from the second half of the Quattrocento; the best represented artist is obviously Andrea Verrocchio, who gave his name to the room. Dominating the centre of the room is his famous bronze David commissioned by the Medici family.

Art in Tuscany | The National Bargello Museum

|

| This article uses material from the Wikipedia articles Donatello, Battistero di San Giovanni (Siena) and Siena Duomo. The text on this page is adapted from www.wikipedia.org, under GNU Free Documentation License. Biography content is available under a Creative Commons License. |

Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects, Volume II: Berna to Michelozzo Michelozzi | Donato [Donatello]

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Donatello, by David Lindsay, Earl of Crawford

|

|

| Donatello: Madonna con Bambino e due angeli (particolare) - Prato, Museo Civico |

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()