| |

|

The Basilica di Santa Croce (Basilica of the Holy Cross) is the principal Franciscan church in Florence, Italy, and a minor basilica of the Roman Catholic Church. It is situated on the Piazza di Santa Croce, about 800 metres south east of the Duomo. The site, when first chosen, was in marshland outside the city walls. It is the burial place of some of the most illustrious Italians, such as Michelangelo, Galileo, Machiavelli, Foscolo, Gentile and Rossini, thus it is known also as the Temple of the Italian Glories (Tempio dell'Itale Glorie).[1]

The Basilica is the largest Franciscan church in the world. Its most notable features are its sixteen chapels, many of them decorated with frescoes by Giotto and his pupils, and its tombs and cenotaphs. Legend says that Santa Croce was founded by St Francis himself. The building's design reflects the austere approach of the Franciscans.

In the picturesque cloister to the side of the Church of Santa Croce one finds the Pazzi Chapel, built under the direction of Filippo Brunelleschi in a discreet cloister of the Franciscan church, Santa Croce. After some early agreements, the chapel was begun in 1442. It is one of the incunabula of Renaissance architecture: severely restrained, made of pietra serena and white plaster, and unrelieved by color. A hemispherical dome (completed after Brunelleschi's death following his plans) caps a cubical sacristy for the Franciscan church: within it the Pazzi family were permitted to bury their dead.

|

|

Firenze, Chiesa di Santa Croce, old facade. In the 19th century the church received a new bell tower (by Gaetano Baccani, 1847)

and a marble façade (designed by Nicola Matas, 1853-63), in the neo-gothic style

|

| The present basilica, traditionally attributed to Arnolfo di Cambio, was built from 1295, on the site where, around 1210, the first Franciscan friars to arrive in Florence had a small oratory.

Santa Croce is planned as an Egyptian cross, with an open timber roof; there are many tomb slabs set into the pavement. The nave is wide and well-lit, with massive widely-spaced piers supporting pointed arches. On entering the basilica, in the Florentine gothic style, our attention is immediately drawn to the east end, where the tall narrow stained glass windows pierce the walls beneath the vaulting.

A fundamental feature of early Franciscan churches was the frescoed narration, in simple and clear terms, of the stories of Christ, of St Francis and of other saints. Several of the great Florentine families, including the Bardi, the Peruzzi, the Alberti, the Baroncelli and the Rinuccini, acquired the patronage of chapels in Santa Croce, thereby assuming the honour of decorating and furnishing them. Some of this 14th-century decoration has survived down to our own time, including that painted by the great Giotto, who frescoed the chapels of the banking families Bardi and Peruzzi (1320-25), respectively with Scenes from the life of St Francis and Scenes from the lives of St John the Baptist and St John the Evangelist. Giotto’s closest followers, Taddeo Gaddi, Bernardo Daddi and Maso di Banco painted frescoes in the chapels patronised by the Baroncelli, the Pulci and Berardi, and the Bardi di Vernio. From the mid-14th century the walls of the aisles and the Sacristy were frescoed by Andrea Orcagna, Giovanni da Milano, Niccolò di Pietro Gerini and Agnolo Gaddi.

The fourteenth-century decoration was crowned by Agnolo Gaddi’s frescoes for the Chapel of the high altar, commissioned by the Alberti and illustrating the Story of the True Cross.

The Sacristy, which includes the Rinuccini Chapel, is reached from the south transept. Its well-preserved frescoes and original 14th-century furnishings give a good idea of how the whole church must have looked in the 14th century when it was completely covered with paintings. In the following century Santa Croce received some important architectural additions. In 1429 Andrea de’ Pazzi undertook the construction of the Chapter House (known as the Pazzi Chapel), which was designed and begun by Filippo Brunelleschi, but not completed until long after his death. It is one of the most harmonious buildings of the Florentine Renaissance, and is decorated not by frescoes but by glazed terracotta roundels, made by Luca della Robbia and his followers.

The Chapel of the Noviciate, which Michelozzo built around 1445 for Cosimo de’ Medici, has a glazed terracotta altarpiece by Andrea della Robbia, of the Madonna and Child with Saints.

The wooden Crucifix in the Bardi di Vernio Chapel in the left transept, and the stone Annunciation (commissioned by the Cavalcanti) in the right aisle, are both by Donatello.

The pulpit carved in relief by Benedetto da Maiano (c. 1475), with Scenes from the life of St Francis, is one of the most beautiful in Florence.[2]

It is significant that Santa Croce, which was to become the resting-place of so many great Italians, has the first truly renaissance funerary monument: the tomb of Leonardo Bruni, Chancellor of the Republic, sculpted by Bernardo Rossellino (1444). Bruni’s successor, Carlo Marsuppini, is buried in another fine renaissance tomb on the other side of the nave, by Desiderio da Settignano (c. 1455), which follows the same scheme. From then on, the history of the Santa Croce is marked by its tombs.

Michelangelo, who died in Rome in 1564, was buried here beneath a monument with allegorical figures of Sculpture, Architecture and Painting, designed by Giorgio Vasari. Michelangelo’s tomb served as the model for others, such as the tomb of Galileo, who died in 1642 (his monument was made by Giovanni Battista Foggini).

Funerary monuments continued to be added to the interior, including ones to Niccolò Machiavelli, Vittorio Alfieri, Gioachino Rossini and the cenotaph to Dante Alighieri (1829). Ugo Foscolo, who died in England, was reburied here in 1871; in his celebrated Sepolcri he had written of the Santa Croce tombs as ‘urns of the strong, that kindle strong souls to great deeds’, and had thereby given rise to the secular view of the basilica as a Pantheon of civic memories. In the 19th century the church received a new bell tower (by Gaetano Baccani, 1847) and a marble façade (designed by Nicola Matas, 1853-63), in the neo-gothic style.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Facciata di Santa Croce - Invenzione della croce di Titto Sarrocchi

|

|

Facciata di Santa Croce - Trionfo della croce di Giovanni Duprè |

|

Visione di Costantino di Emilio Zocchi |

|

|

Emilio Burci, View of the Piazza Santa Croce, mid-19th century, copper engraving, 9.9 x 16.6 cm, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz [0]

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Cappella Maggiore, Basilica

di Santa Croce, Firenze, view of the Interior

|

The interior of the Franciscan church of Santa Croce, with the high altar area in the centre, with a fresco cycle of 1388-93 by Agnolo Gaddi to the left, and the fresco cycle of the Bardi Chapel by Giotto (1320s) to the right. Initiated by the Franciscans around 1388, Gaddi’s is the earliest monumental True Cross program; it set the standard for similar works into the sixteenth century.

|

|

Agnolo Gaddi | The Legend of the True Cross

|

|

|

Agnolo Gaddi (c.1350–1396) was an Italian painter. He was born and died in Florence, and was the son of the painter Taddeo Gaddi.

Taddeo Gaddi was himself the major pupil of the Florentine master Giotto. Agnolo was an influential and prolific artist who was the last major Florentine painter stylistically descended from Giotto.

Giorgio Vasari included a biography of Agnolo Gaddi in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

Agnolo Gaddi received the commission to paint the high chapel at Santa Croce around 1380 from the Alberti family. Although the chapel is the largest and arguably the most important in the church, it was the last to be painted – around it were 5 chapels painted by Giotto and his school.

The inspiration for the mural cycle in the apse derived from the dedication of the church to the True Cross and from the celebration of Santa Croce’s most sacred relic, a splinter of the True Cross, which was housed in a reliquary built by the Venetian goldsmith Bertucci in 1258.

The Legend of the True Cross is told in eight scenes, reading from top to bottom, first on the right side (looking at the altar), then on the left. The artist followed the text closely, guided likely by the Franciscans, while also working to satisfy the Alberti patrons and, as much as possible, to satisfy his own interests in running a large workshop.

Art in Tuscany | Agnolo Gaddi | The Legend of the True Cross

|

|

Two representatives of the Alberti family, a wealthy and influential Florentine banking family who were highly involved in the patronage of art.

|

|

Agnolo Gaddi, The Legend of the True Cross, Chosroes Worshipped by His Subjects, The Dream of Heraclius, and The Defeat of the Son of Chosroes

|

The Peruzzi and Bardi Chapels

|

|

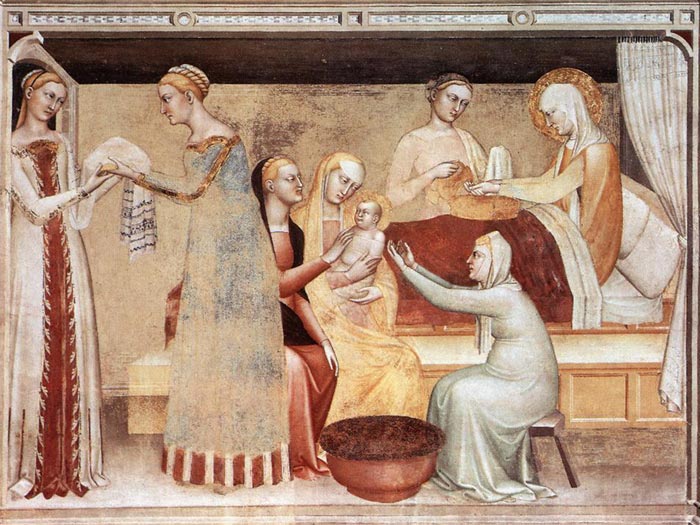

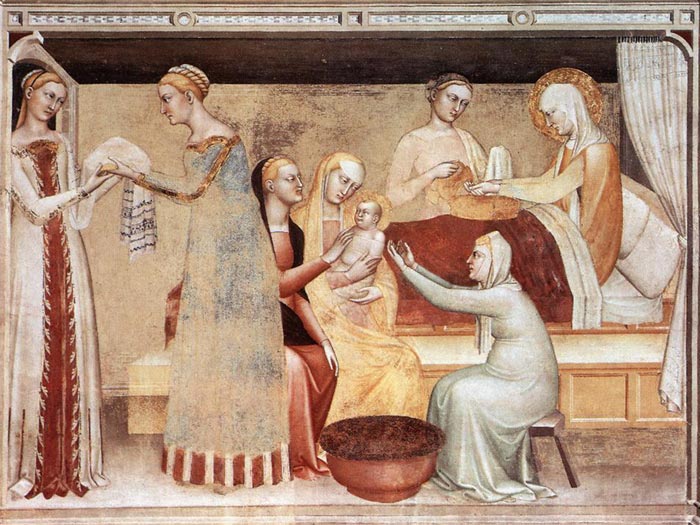

Giovanni Da Milano, The Birth of the Virgin, 1365, fresco, Rinuccini Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

The Sacristy, which includes the Rinuccini Chapel, is reached from the south transept. Its well-preserved frescoes and original 14th-century furnishings give a good idea of how the whole church must have looked in the 14th century when it was completely covered with paintings.

Giovanni da Milano, a Lombard painter settled in Florence around 1360, was commissioned by Lapo di Lizio Guidalotti (died c. 1350) to execute a modest fresco cycle in the Rinuccini Chapel of the Franciscan church of Santa Croce in Florence. The artist painted 5-5 scenes to the side walls of the chapel from the life of the Virgin and Magdalene. The scenes can be considered as variants of the cycles in the Baroncelli Chapel in the Santa Croce (by Taddeo Gaddi) and in the Magdalene Chapel in the Lower Church of the San Francesco in Assisi (by Giotto's circle). [3]

According to Lorenzo Ghiberti, Giotto painted chapels for four different Florentine families in the church of Santa Croce.[4] The Peruzzi Chapel pairs 3 frescoes from the life of St. John the Baptist (The Annunciation of John's Birth to his father Zacharias; The Birth and Naming of John; The Feast of Herod) on the left wall with 3 scenes from the life of St. John the Evangelist (The Visions of John on Ephesus; The Raising of Drusiana; The Ascension of John) on the right wall. The choice of scenes has been related to both the patrons and the Franciscans.[25] Because of the serious condition of the frescoes, it is difficult to discuss Giotto's style in the chapel, although the frescoes show signs of his typical interest in controlled naturalism and psychological penetration. The Peruzzi Chapel was especially renowned during Renaissance times. Giotto's compositions influenced Masaccio's Cappella Brancacci, and Michelangelo is known to have studied the frescoes.

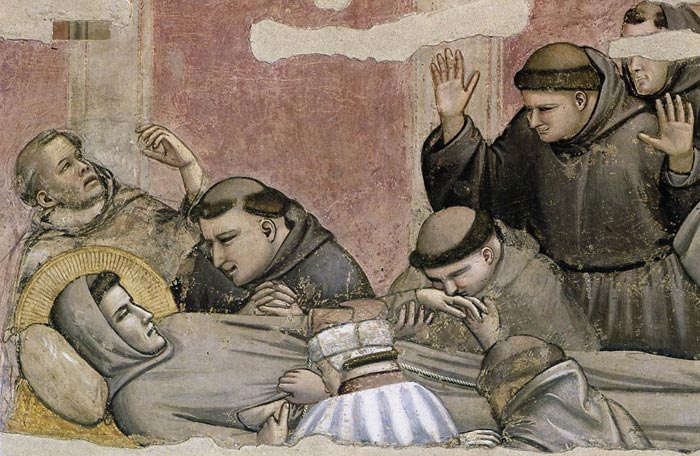

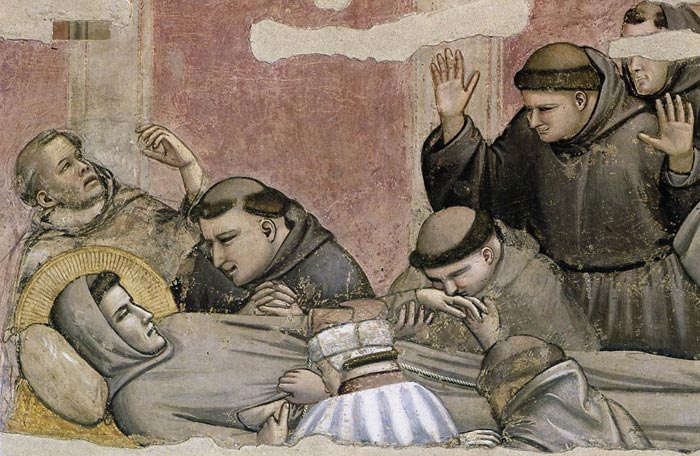

The Bardi Chapel is of particular interest as it depicts the life of St. Francis, following a similar iconography to the frescoes in the Upper Church at Assisi, dating from 20–30 years earlier. A comparison makes apparent the greater attention given by Giotto to expression in the human figures and the simpler, better-integrated architectural forms. Giotto represents only 7 scenes from the saint's life here, and the narrative is arranged somewhat unusually. The story starts on the upper left wall with St. Francis Renounces his Father. It continues across the chapel to the upper right wall with the Approval of the Franciscan Rule, moves down the right wall to the Trial by Fire, across the chapel again to the left wall for the Appearance at Arles, down the left wall to the Death of St. Francis, and across once more to the posthumous Visions of Fra Agostino and the Bishop of Assisi. The Stigmatization of St. Francis, which chronologically belongs between the Appearance at Arles and the Death, is located outside the chapel, above the entrance arch. This arrangement encourages viewers to link scenes together: to pair frescoes across the chapel space or relate triads of frescoes along each wall. These linkings suggest meaningful symbolic relationships between different events in St. Francis's life.

In 1334 Giotto was appointed chief architect to Florence Cathedral, of which the Campanile (founded by him on July 18, 1334) bears his name, but was not completed to his design.

"The first of the great personalities in Florentine painting was Giotto," begin Bernard Berenson's classic portrait of the fourteenth-century artist in his Italian Painters of the Renaissance. The Santa Croce frescoes are still among his most admired works (despite continuing uncertainty, as with most of the works ascribed to him, that they were actually painted by him)--one of the achievements that, as Berenson suggested, "will make him a source of highest aesthetic delight for a period at least as long as decipherable traces of his handiwork remain on mouldering panel or crumbling wall."

Giotto di Bondone | The Bardi Chapel and the Peruzzi Chapel in Santa Croce, Florence

The Baroncelli Chapel is located at the transept's end of the church of Santa Croce. It has frescoes by Taddeo Gaddi executed between 1328 and 1338.

The fresco cycle represents the Stories of the Virgin. In this work, Gaddi showed his mastership of Giotto's style, with a narrative disposition of the characters in the scenes, which are more crowded than his master's. He also continued to experiment the use of geometrical perspective in the architectural background, obtaining illusionistic effects in details such as the oblique staircase in the Presentation at the Temple. The two niches with still lives in the basement are perhaps inspired to Giotto's ones in the Scrovegni Chapel.

The delicate and soft features are characteristic of Gaddi's late style. The adoption of night light in the Annunciation to the Shepherds is nearly unique in the mid-14th century painting of central Italy.

The upper part of the fresco cycle depicts the scenes Joachim Driven from the Temple and the Annunciation to Joachim.

The middle part of the fresco cycle depicts the Meeting at the Golden Gate and the Birth of St John the Baptist.

The lower part of the fresco cycle depicts the Virgin on her Way to the Temple, and the Betrothal to Joseph.

Gaddi also designed the stained glasses, with four prophets on the exterior, and perhaps had a hand in the altarpiece also: this, dating to c. 1328, has the signature Opus Magistri Jocti, but the style show the massive interventions of assistants, including Gaddi himself. It is an elaborate polyptych, depicting the Coronation of the Virgin surrounded by a crowded Glory of Angels and Saints. The cups of the altarpiece is now at the Timken Art Gallery of San Diego, California, United States. The original frame was replaced by a new one during the 15th century.

Other artworks in the chapel include, on the right wall, a Madonna of the Cintola by Sebastiano Mainardi. The Baroncelli family owned the tomb on the external wall, which was designed by Giovanni di Balduccio in 1327; the latter also sculpted the statuettes of the Archangel Gabriel and the Annunciation on the arcade's pillars. The Madonna with Child sculpture inside the chapel is by Vincenzo Danti (1568).

Taddeo Gaddi | Frescoes in the Santa Croce, Florence

|

|

View of the Peruzzi and Bardi Chapels

Bastiano Mainardi, Assumption of the Virgin with the Gift of the Girdle, fresco, Santa Croce, Florence Bastiano Mainardi, Assumption of the Virgin with the Gift of the Girdle, fresco, Santa Croce, Florence

This monumental wall painting is in the Cappella Baroncelli in Santa Croce, Florence. According to Vasari it is the work of Bastiano Mainardi, but it is based on preliminary studies and cartoons by Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Taddeo Gaddi, Baroncelli Chapel, Frescoes of the life of St. Francis

|

| |

|

|

Scenes from the Life of Saint Francis, Death and Ascension of St Francis

|

|

Scenes from the Life of Saint Francis, Death and Ascension of St Francis, (detail), c. 1325, fresco, 280 x 450 cm, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

Taddeo Gaddi, Last Supper, Tree of Life and Four Miracle Scenes

|

|

Taddeo Gaddi, Last Supper, Tree of Life and Four Miracle Scenes, 1360s, Fresco, 1120 x 1170 cm, Santa Croce, Florence

|

|

|

|

In the picturesque cloister to the side of the Church of Santa Croce one finds one of the greatest works by Filippo Brunelleschi: the Pazzi Chapel. It dates from just three years before the death of the architect (1443) and is considered to be one of the masterpieces of Renaissance architecture. The plan of the chapel is again the circle and the square. A rectangular base is covered with a conical central dome supported by fine "veiled" vaulting that one also finds in the porch. The spaces are divided up with a geometric lucidity; the white intonaco (plaster) of the walls is in the cool contrast to the pilasters in grey "serene" stone, and the beautiful decorations in glazed terracotta which adorn the interior are by Luca della Robbia.

The Pazzi family were Tuscan nobles who were bankers in Florence in the 15th century. They are now best known for the "Pazzi conspiracy" to murder Lorenzo de' Medici and Giuliano de' Medici on 26 April 1478 (Lorenzo escaped) [4]. Andrea de' Pazzi was also the patron for the chapter house for the Franciscan community at Florence's Santa Croce church, often known as the Pazzi Chapel. After the conspiracy, the remaining Pazzi were rehabilitated and returned to Florence.

In the same courtyard there is the long refecotry housing the dramatic CRUCIFIX by Cimabue. Dating from c. 1270 (see Opera St.Croce museum) this was the work of art most damaged in the flood of 1966.

Ten years time was necessary for the restoration of the panel painting. After lying immersed in the mud for an entire day.

|

|

Pazzi Chapel, Cappella de' Pazzi |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

In front of the Basilica of Santa Croce is located a marble statue made by Enrico Pazzi decidated to Dante Alighieri.

For Dante, exile was nearly a form of death, stripping him of much of his identity and his heritage. He addresses the pain of exile in Paradiso, XVII (55-60),

where Cacciaguida, his great-great-grandfather, warns him what to expect:

Mural of Dante in the Uffizi Gallery, by Andrea del Castagno, c. 1450

... Tu lascerai ogne cosa diletta ... You shall leave everything you love most:

più caramente; e questo è quello strale this is the arrow that the bow of exile

che l'arco de lo essilio pria saetta. shoots first. You are to know the bitter taste

Tu proverai sì come sa di sale of others' bread, how salty it is, and know

lo pane altrui, e come è duro calle how hard a path it is for one who goes

lo scendere e 'l salir per l'altrui scale ... ascending and descending others' stairs ...

As for the hope of returning to Florence, he describes it as if he had already accepted its impossibility, (Paradiso, XXV, 1–9):

Se mai continga che 'l poema sacro If it ever come to pass that the sacred poem

al quale ha posto mano e cielo e terra, to which both heaven and earth have set their hand

sì che m'ha fatto per molti anni macro, so as to have made me lean for many years

vinca la crudeltà che fuor mi serra should overcome the cruelty that bars me

del bello ovile ov'io dormi' agnello, from the fair sheepfold where I slept as a lamb,

nimico ai lupi che li danno guerra; an enemy to the wolves that make war on it,

con altra voce omai, con altro vello with another voice now and other fleece

ritornerò poeta, e in sul fonte I shall return a poet and at the font

del mio battesmo prenderò 'l cappello ... of my baptism take the laurel crown ...

Prince Guido Novello da Polenta invited him to Ravenna in 1318, and he accepted. He finished the Paradiso, and died in 1321 (at the age of 56) while returning to Ravenna from a diplomatic mission to Venice, possibly of malaria contracted there. Dante was buried in Ravenna at the Church of San Pier Maggiore (later called San Francesco). Bernardo Bembo, praetor of Venice in 1483, took care of his remains by building a better tomb.

Eventually, Florence came to regret Dante's exile, and made repeated requests for the return of his remains. The custodians of the body at Ravenna refused to comply, at one point going so far as to conceal the bones in a false wall of the monastery. Nevertheless, in 1829, a tomb was built for him in Florence in the basilica of Santa Croce. That tomb has been empty ever since, with Dante's body remaining in Ravenna, far from the land he loved so dearly. The front of his tomb in Florence reads Onorate l'altissimo poeta—which roughly translates as "Honour the most exalted poet". The phrase is a quote from the fourth canto of the Inferno, depicting Virgil's welcome as he returns among the great ancient poets spending eternity in Limbo. The continuation of the line, L'ombra sua torna, ch'era dipartita ("his spirit, which had left us, returns"), is poignantly absent from the empty tomb.

Art in Tuscany | Dante Alighieri

|

|

|

| |

Home Page | http://www.operadisantacroce.it/

BBC video about Giotto frescoes in the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence | www.news.bbc.co.uk

The restoration site in Santa Croce

The much-awaited guided tours of the restoration site of the frescoes in Santa Croce, the great Florentine basilica of the Holy Cross, have finally begun. The eight frescoes on the side walls of the Cappella Maggiore, painted in 1380 by Agnolo Gaddi and depicting the Legend of the True Cross, are now being restored. This is a unique opportunity to come face-to-face with the works of this great artist influenced by Giotto. The tour of the restoration site includes gradual ascension up 7 levels, for a total of 90 steps. There are three stops for explanations of the works. For safety reasons, access is only allowed to children over 12.

The tours, which last approximately 40 minutes, start on 16th May. The guided groups will include a maximum of 15 visitors. Booking required. Timetable of guided tours: from Monday to Friday at 10 am - 11 am - 12 noon - 2 pm - 3 pm - 4 pm.

The ticket costs € 13.00 and also allows entrance to the Basilica, the cloisters and the museum. Reservations can be made by phone from 10 am to 2 pm (tel. +39 055 2466105 - dial 3) or else by e-mail booking@santacroceopera.it , specifying the date and time of the visit, the number of people, a cell-phone number to contact, the names and dates of birth of the participants.

(From Apt - Agenzia per il Turismo di Firenze (Florence Official Tourist Office)

Bibliography

Damien Wigny, Au coeur de Florence : Itinéraires, monuments, lectures, 1990

[0] Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz | City Palaces

Address: Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, Via Giuseppe Giusti 44, 50121 Firenze

The Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz is one of the oldest research institutions dedicated to the History of Art and Architecture in Italy. Zoege von Manteufel was the director of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence and developed the prints collection into one of the most representative collections in the west. The “creation of a large collection of illustrations suitable for comparative studies” was one of the main aims of the Kunsthistorisches Institute in Florence right from its establishment in 1897. This early collection, which came from donations and bequests, contains not only conventional photographic material but also engravings and prints.

[1] Funerary monuments | The Basilica became popular with Florentines as a place of worship and patronage and it became customary for greatly honoured Florentines to be buried or commemorated there. Some were in chapels "owned" by wealthy families such as the Bardi and Peruzzi. As time progressed, space was also granted to notable Italians from elsewhere. For 500 years monuments were erected in the church including those to:

Leon Battista Alberti (15th century architect and artistic theorist)

Vittorio Alfieri (18th century poet and dramatist)

Eugenio Barsanti (co-inventor of the internal combustion engine)

Lorenzo Bartolini (19th century sculptor)

Julie Clary, wife of Joseph Bonaparte, and their daughter Charlotte Napoléone Bonaparte

Leonardo Bruni (15th century chancellor of the Republic, scholar and historian)

Dante (actually buried in Ravenna)

Ugo Foscolo (19th century poet)

Galileo Galilei

Giovanni Gentile (20th century philosopher)

Lorenzo Ghiberti

Niccolò Machiavelli by Innocenzo Spinazzi

Carlo Marsuppini (15th century chancellor of the Republic)

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Raffaello Morghen (19th century engraver)

Gioacchino Rossini

Louise of Stolberg-Gedern (wife of Charles Edward Stuart)

Guglielmo Marconi (actually buried in his birthplace at Sasso Marconi, near Bologna)

Enrico Fermi (actually buried in Chicago, Illinois)

[2] Artists whose work is present in the church include:

Benedetto da Maiano (pulpit; doors to Cappella dei Pazzi, with his brother Giuliano)

Antonio Canova (Alfieri's monument)

Cimabue (Crucifixion, badly damaged by the 1966 flood and now in the refectory)

Andrea della Robbia (altarpiece in Cappella Medici)

Luca della Robbia (decoration of Cappella dei Pazzi)

Desiderio da Settignano (Marsuppini's tomb; frieze in Cappella dei Pazzi)

Donatello (relief of the Annunciation on the south wall; crucifix in the lefthand Cappella Bardi; St Louis of Toulouse in the refectory, originally made for the Orsanmichele)

Agnolo Gaddi (frescoes in Cappella Castellani and chancel; stained glass in chancel)

Taddeo Gaddi (frescoes in Cappella Baroncelli; Crucifixion in the sacristy; Last Supper in the refectory, considered his best work)

Giotto (frescoes in Cappella Peruzzi and righthand Cappella Bardi; possibly Coronation of the Virgin, altarpiece in Cappella Baroncelli)

Giovanni da Milano (frescoes in Cappella Rinuccini) with Scenes of the Life of the Virgin and the Magdalen

Maso di Banco (frescoes in Cappella Bardi di Vernio) depicting Scenes from the life of St.Sylvester (1335–1338).

Henry Moore (statue of a warrior in the Primo Chiostro)

Andrea Orcagna (frescoes largely disappeared during Vasari's remodelling, but some fragments remain in the refectory)

Antonio Rossellino (relief of the Madonna del Latte (1478) in the south aisle)

Bernardo Rossellino (Bruni's tomb)

Santi di Tito (Supper at Emmaus and Resurrection, altarpieces in the north aisle)

Giorgio Vasari (Michelangelo's tomb) with sculpture by Valerio Cioli, Iovanni Bandini, and Battista Lorenzi. Way to Calvary painted by Vasari[4].

Domenico Veneziano (SS John and Francis in the refectory)

Once present in the church's Medici Chapel, but now split between the Florentine Galleries and the Bagatti Valsecchi Museum in Milan, is a polyptych by Lorenzo di Niccolò.

[3] Originally Giovanni di Jacopo di Guido da Caversaccio. He came from Lombardy and is first recorded in Florence on 17 October 1346, listed as Johannes Jacobi de Commo among the foreign painters living in Florence. There follows a gap of at least 12 undocumented years until his inscription as Johannes Jacobi Guidonis de Mediolano with the Arte dei Medici e Speziali between 1358 and 1363. A tax return dated 26 December 1363 declares his ownership of land in Ripoli, Tizzana (nr Prato) and a house in the parish of S Pier Maggiore, Florence.

His earliest signed work, a polyptych in the Pinacoteca at Prato, was commissioned by 1363. This was followed by a Pietà dated 1365, now in the Accademia, Florence. He was influenced by the Sienese painter Simone Martini, but his forms have a solidity that looks back to Giotto. His mature style is associated with a linear grace.

[4] As with almost everything in Giotto's career, the dates of the fresco decorations that survive in Santa Croce are disputed. The Bardi Chapel, immediately to the right of the main chapel of the church, was painted in true fresco, and to some scholars the simplicity of its settings seems relatively close to those of Padua, while the Peruzzi Chapel's more complex settings suggest a later date.[23] The Peruzzi Chapel is adjacent to the Bardi Chapel and was largely painted a secco. This technique, quicker but less durable than true fresco, has resulted in a fresco decoration that survives in a seriously deteriorated condition. Scholars who date this cycle earlier in Giotto's career see the growing interest in architectural expansion that it displays as close to the developments of the giottesque frescoes in the Lower Church at Assisi, while the Bardi frescoes have a new softness of color that indicates the artist going in a different direction, probably under the influence of Sienese art, and so must be a later development.

|

[5] The conspiracy | Less powerful than, and rivals of, the Medici, the Pazzi were caught up in a conspiracy to replace the Medici as rulers of Florence.

The Pazzi family were not the only instigators - the Salviati, Papal bankers in Florence, were at the center of the conspiracy. Pope Sixtus IV was an enemy of the Medici. He had purchased from Milan the lordship of Imola, a stronghold on the border between Papal and Tuscan territory that Lorenzo de' Medici wanted for Florence. The purchase was financed by the Pazzi bank, even though Francesco dei Pazzi had promised Lorenzo they would not aid the Pope. As a reward, Sixtus IV granted the Pazzi monopoly at the alum mines at Tolfa — alum being an essential mordant in dyeing in the textile trade that was central to the Florentine economy — and he assigned to the Pazzi bank lucrative rights to manage Papal revenues. Sixtus IV appointed his nephew, Girolamo Riario, as the new governor of Imola, and Francesco Salviati as archbishop of Pisa, a city that was a former commercial rival but now subject to Florence. Lorenzo had refused to permit Salviati to enter Pisa because of the challenge such an ecclesiastical position offered to his own government in Florence.

Salviati and Francesco de' Pazzi put together a plan to assassinate Lorenzo and Giuliano de' Medici. Riario himself remained in Rome. The plan was widely known: the Pope was reported to have said, "I support it — as long as no one is killed." In 2004, an encrypted letter in the archives of the Ubaldini family was discovered by Marcello Simonetta, a historian then teaching at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, and decoded. It revealed that Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, a renowned humanist and condottiere for the Papacy, was deeply embroiled in the conspiracy and had committed himself to position 600 troops outside Florence, waiting for the moment.

On Sunday, 26 April 1478, during High Mass at the Duomo before a crowd of 10,000, the Medici brothers were assaulted. Giuliano de' Medici was stabbed 19 times by a gang that included a priest. As he bled to death on the cathedral floor, his brother Lorenzo escaped with serious, but non life-threatening wounds. Lorenzo reappeared shortly after, locked safely in the sacristy by the humanist Poliziano. A coordinated attempt to capture the Gonfaloniere and Signoria was thwarted when the archbishop and head of the Salviati clan were trapped in a room whose doors had a hidden latch. The coup d'état had failed, and the enraged Florentines seized and killed the conspirators. Jacopo de' Pazzi was tossed from a window. To finish him off, the mob dragged him naked through the streets, then threw him into the Arno River. The Pazzi family were stripped of their possessions in Florence, every vestige of their name effaced. Salviati was hanged on the walls of the Palazzo della Signoria. Although Lorenzo appealed to the crowd not to exact summary justice, many of the conspirators, as well as many people accused of being conspirators, were killed. Lorenzo did manage to save the nephew of Sixtus IV, Cardinal Raffaele Riario, who was almost certainly an innocent dupe of the conspirators, as well as two relatives of the conspirators. The main conspirators were hunted down throughout Italy and the fortunes of the various Pazzi companies across Europe were despoiled. The Pazzi crest and all references to their name were banned. In 1494, however, with the overthrow of Piero de' Medici, the Pazzi family, and many other political exiles, returned to Florence to participate in the popular government.

In the aftermath of the "Pazzi" conspiracy, Pope Sixtus IV placed Florence under interdict, forbidding Mass and communion, for the execution of the Salviati archbishop. Sixtus enlisted the traditional Papal military arm, the King of Naples, Ferdinand I, to attack Florence. With no help coming from Florence's traditional allies in Bologna and Milan, Lorenzo was faced with dire prospects and adopted an unorthdox course of action: he sailed to Naples and put himself in the hands of Don Ferrante (the king), in whose custody he remained for three months. Lorenzo's courage and charisma convinced Don Ferrante to support Lorenzo's attempts at brokering a peace and intercede, albeit ineffectually, with Sixtus IV.

The conspirators, Francesco de' Pazzi, Bernardo di Bandino Baroncelli, Archbishop Salviati, Vieri de' Pazzi, Messer Jacopo de' Pazzi, Antonio Maffei and Stefano de Bagnone, were depicted in a painting by Sandro Botticelli on either a wall of the Bargello or a wall of the Dogana, part of the government-complex. Rodrigo Borgia, the Pope Alexander VI pressured Florence to remove these lifelike pictures, and they were eventually destroyed in 1494.

Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence | The 1966 Flood in Florence

|

|

Leonardo da Vinci, drawing of

a hanged

Pazzi conspirator Bernardo di Bandino Baroncelli, 1479 |

In 1966, the Arno River flooded much of Florence, including Santa Croce. The water entered the church bringing mud, pollution and heating oil. The damage to buildings and art treasures was severe, taking several decades to repair.

Santa Croce was the first populated area to be overflowed by the flood. This area remained under the water longer compared to the others because it's lower with respect to the river. The Arno river completely filled the Cloister, it penetrated into the crypt, it disrupted the tombs of the Church. The works of removing the mud and the rubble took about two months. But the damages didn't finish here: the Franciscan fathers and those in charge of the Belle Arti saw the most devastating reality: the Crucifix by Cimabue, located in the Museum inside the big Franciscan refectory, was destroyed. Among great difficulties the heavy painted cross, drenched with water, was brought down and laid in a horizontal position. It took six hours to accomplish this difficult task, while the flakes of colour detached and fell in the mud. The mud was sieved and some fragments were recovered.

The statue of Dante, now in front of the church, was still in the middle of the piazza in 1966

Millions of books and documents stored in the basement of the Biblioteca Nazionale, adjacent to Santa Croce (and to the river), were submerged in oily mud; the water covered the tombs in the church and stained the frescoes by Giotto in the Peruzzi Chapel. And Cimabues famous crucifix, in the Museum of Santa Croce, was destroyed beyond hope of restoration, despite heroic attempts by the monks to salvage even the smallest bits of gold and flecks of paint from the oily muck that remained when the water had subsided. In the words of Sir Kenneth Clark (in The Nude) the Cimabue crucifix marked a return, after the middle ages, to a conception of the human body as "a controlled and canonized vehicle of the divine".

Some people were impatient with Cimabue, however, especially in the Santa Croce quarter, the quarter of the popolo minute, the little people, the artisans-leather workers, furniture makers and restorers. antique dealers -- many of whom lost all their possessions, nor only their homes, but their tools as well.

The high water marks for the floods of 1557 and 1966, which can be seen above your head on the north side of the piazza (just around the corner from the Via Verdi) are astonishing.[From Robert Hellenga, Imagining the Flood, p 65, in Travelers' Tales Italy: True Stories, 2001.]

.

|

|

|

“On November 4, 1966, in Florence the Arno river swollen with dark, muddy waters, spilled over

sweeping away everything in its way. When the waters subsided, only destruction enveloped the city.”

4 Novembre 1966. L’alluvione a Firenze

|

|

Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence, after the flood

|

|

Tuscan Holiday houses | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

Podere Santa Pia, with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montecristo

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden |

|

Florence, Duomo

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sant'Antimo, between Santa Pia and Montalcino |

|

Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence |

|

Monte Oliveto Maggiore abbey |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Piazza Santa Croce and the calcio storico

|

|

|

Piazza Santa Croce is one of the largest and most famous squares of central Florence. The Basilica of Santa Croce, the largest Franciscan church in the world, overlooks the piazza.

Aside from the basilica, several important palazzos are on the square. Palazzo Cocchi-Serristori, on the opposite end from the basilica, is the 15th century (with earlier foundations) masterpiece of Giuliano da Sangallo, the personal architect of Lorenzo il Magnifico (with later work also attributed to Baccio d'Agnolo and Simone del Pollaiuolo). Today it houses the headquarters of the First Quarter neighborhood of Florence. In front of the Palazzo there is a baroque fountain originally attributed to Pietro Maria Bardi, constructed in 1673. It was later restored (circa 1816) by Giuseppe Manetti.

On the south side of the square lies the Palazzo dell'Antella (or Antellesi), a long building with a facade decorated with amazing (yet mostly destroyed) frescos by Giovanni da San Giovanni, and with windows of odd sizes (supposedly so that when seen from the steps of the church they all appear to be the same size). Today the ground floor of the Palazzo house shops and restaurants, while the upper floors are run by the Piccolomini family as short term tourist rentals.

The large rectangular shape of the square makes it a perfect place to host events, in particular the famous game of Calcio Fiorentino played every spring between the teams of the four "neighborhoods" of Florence. In 2006, Roberto Benigni recited Dante's Divine Comedy beside the Dante statue on the steps of the basilica. Almost every week a different themed market or festival takes place in the square - the annual Christmas market and the newer chocolate festival are just two examples of the many kinds of activities to discover in the piazza. It is also home to the Florence Marathon in the fall and the Half Marathon in the spring.

Art in Tuscany | Giovanni da San Giovanni (Giovanni Mannozzi)

Calcio Storico

|

|

Palazzo dell'Antella or Palazzo Stufa Palazzo dell'Antella or Palazzo Stufa

|

|

Chiesa di Santa Croce with the old facade. The Duomo and the Basilica di Santa Croce only got their façades in the 19th century.

Image from: Pietro di Lorenzo Bini (ed.), Memorie del calcio fiorentino tratte da diverse scritture e dedicate all'altezze serenissime di Ferdinando Principe di Toscana e Violante Beatrice di Baviera, Firenze, Stamperia di S.A.S. alla Condotta, [1688].

|

Calcio Storico is one of the most strange and old games ever played since the Renaissance. Every June, ancient Florentine soccer is re-enacted in one of Florence's main historical squares, the Piazza Santa Croce. It is said that Calcio Storico Fiorentino is the precursor not only to modern day soccer but also to football and rugby. On February 17th in the year 1530, Florence's Piazza Santa Croce became the arena for a soccer match that the Florentine Republic staged in order to demonstrate to the imperial army of Charles V that the people's spirit was not to be broken after months of invasion. Today's Calcio Fiorentino tournament, held annually the 3rd week of June, is a renactment of this first match, a crucial moment in the history of the city.

Three games are now played each year: two semi-finals and a final, which takes place on 24 June, the Feast of Saint John the Baptist, patron saint of Florence.

The matches were played almost without interruption until the end of the 18th century, and only in May 1930 on the fourth centenary of the siege of Florence was the historical manifestation started up again.*

The competition is between the four historic quarters of the city: San Giovanni (‘Greens’), Santa Maria Novella (‘Reds’), Santa Croce (‘Blues’) and Santo Spirito (‘Whites’). In calcio storico the equivalent of a goal is a caccia. The winning team is awarded a calf. The historic procession starts at 4 p.m. from piazza Santa Maria Novella towards piazza della Repubblica, piazza della Signoria and piazza santa Croce.

Events in Tuscany | Calcio Storico Fiorentino

* In The Renaissance Perfected, Medina Lasansky discusses the ways in which Italy’s fascist government drew upon medieval and Renaissance architectural styles and cultural traditions to gain political support and to strengthen Italy’s international image. She cites the town of Arezzo as an example of the manipulated restoration of medieval and Renaissance structures that took place in Tuscany under the fascist regime, and examines the reinvention of medieval and Renaissance festivals such as Siena’s palio and Florence’s calcio.

[The Renaissance Perfected: Architecture, Spectacle, and Tourism in Fascist Italy. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sant'Antimo, between Santa Pia and Montalcino |

|

Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence |

|

Villa Arceno gardens |

| |

|

|

|

|

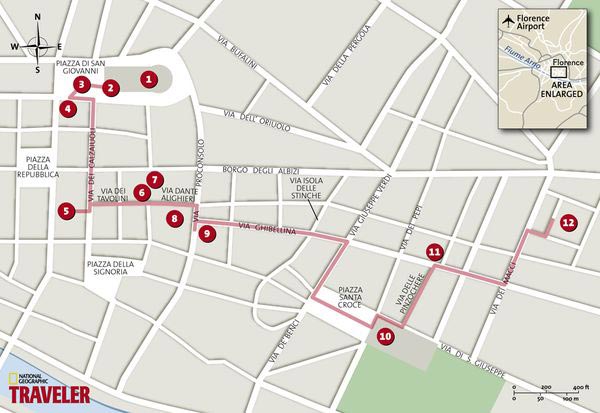

From Piazza del Duomo to Santa Croce

Piazza del Duomo marks Florence’s religious heart, home to the (1) Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (the Duomo) (www.duomofirenze.it); the 14th-century (2) Campanile, or "bell tower"; and the (3) Battistero, or Baptistery. Visit all three before starting this walk, which explores the city’s medieval eastern quarter, a maze of small streets and half-hidden churches rich in historical associations.

Walk south from the piazza on the pedestrian-only Via dei Calzaiuoli, one of the city’s main thoroughfares, noting the pretty (4) Loggia del Bigallo on the right as you exit the square: It was built by a charitable foundation in the 1350s and formed part of an orphanage established by the foundation.

Visit the church of (5) Orsanmichele, midway down Via dei Calzaiuoli on the right at the corner of Via de’ Lamberti (the entrance is to the rear). It is known for its medieval niche statues and for a lovely interior dominated by a grand 14th-century tabernacle and a painting of the Madonna delle Grazie (1347) by Bernardo Daddi.

Almost opposite the church, take Via dei Tavolini and then Via Dante Alighieri. You are now in a district closely associated with the great Florentine poet, Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), author of The Divine Comedy. In the vicinity are the (6) Casa di Dante, or House of Dante (corner of Via Dante Alighieri and Via Santa Margherita; www.museocasadidante.it), a small museum devoted to the poet; (7) Santa Margherita, at Via Santa Margherita, near the corner with Via del Corso, the church where the poet may have married; and the (8) Badia Fiorentina, (go down Via Dante Alighieri and make a right on Via del Proconsolo), the parish church of Beatrice Portinari, Dante’s lifelong muse.

At the Badia, turn right on Via del Proconsolo to the (9) Bargello, directly across the way at Via del Proconsolo 4, once Florence’s medieval police headquarters, prison, and place of execution. Today it houses the cream of Florence’s medieval, Renaissance, and baroque sculpture, as well as numerous beautiful salons devoted to the decorative arts.

East of the Bargello you can meander almost at random, getting happily lost in the old streets en route to the 13th-century church of (10) Santa Croce in Piazza Santa Croce. The best route is down Via Ghibellina, if only because near its conclusion, a tiny right turn, Via Isola delle Stinche, takes you to the Il Gelato Vivoli (on the right at No.7R), widely considered to be Italy’s best ice cream.

Santa Croce is equally mouthwatering; the must-see church in Florence, thanks to numerous important early frescoes by Giotto and others, along with the tombs of some of the city’s most illustrious men and women, including Michelangelo, Machiavelli, and Galileo.

Few visitors venture beyond Santa Croce, but the Sant’Ambrogio district to the north and east is worth the extra effort. Take Via delle Pinzochere off the north side of Piazza Santa Croce to the (11) Casa Buonarroti, (Via Ghibellina 70 near Via Michelangelo Buonarroti), a stylish museum devoted to Michelangelo.

Walk east from the museum on Via Ghibellina and turn left on Via dei Macci. A short way up on the right is the (12) Sant’Ambrogio market, focus of an increasingly chic neighborhood of cafés and specialty stores.

|

|

|

National Geographic | www.nationalgeographic.com/florence-walking-tour-2

Florence | Transport

|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Santa Croce (Florence), the Peruzzi Chapel, Bardi Chapel and Rinuccini Chapel (Basilica of Santa Croce) |

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()