|

|

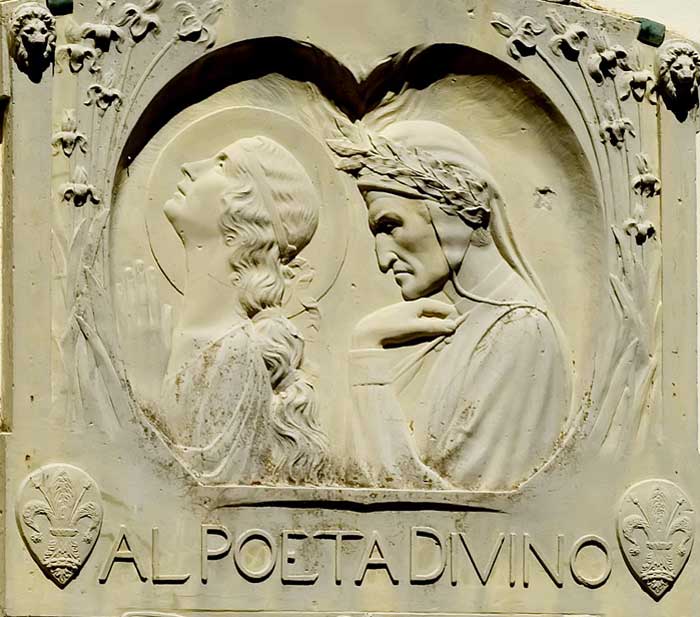

Statue of Dante in the Piazza di Santa Croce in Florence [picture by Ron Reznick | ronreznick.photoshelter.com] [0]

|

|

Dante Alighieri |

Dante Alighieri (May/June c.1265 – September 14, 1321), commonly known as Dante, was an Italian poet of the Middle Ages. He was born in Florence. Dante's engagement with philosophy cannot be studied apart from his vocation as a writer, in which he sought to raise the level of public discourse by educating his countrymen and inspiring them to pursue happiness in the contemplative life. Dante wished to summon his audience to the practice of philosophical wisdom, though by means of truths embedded in his own poetry, rather than mysteriously embodied in scripture. His Divina Commedia, originally called Commedia by the author and later nicknamed Divina by Boccaccio, is often considered the greatest literary work composed in the Italian language and a masterpiece of world literature.

Dante died and is buried in Ravenna. |

|||

| Life |

|||

Dante was born in 1265 in Florence. At the age of 9 he met for the first time the eight-year-old Beatrice Portinari, who became in effect his Muse, and remained, after her death in 1290, the central inspiration for his major poems. Between 1285, when he married and began a family, and 1302, when he was exiled from Florence, he was active in the cultural and civic life of Florence, served as a soldier and held several political offices.

Dante's family was prominent in Florence, with loyalties to the Guelphs, a political alliance that supported the Papacy and which was involved in complex opposition to the Ghibellines, who were backed by the Holy Roman Emperor. The poet's mother was Bella degli Abati. She died when Dante was not yet ten years old. Dante fought in the front rank of the Guelph cavalry at the battle of Campaldino (June 11, 1289). This victory brought forth a reformation of the Florentine constitution. To take any part in public life, one had to be enrolled in one of "the arts". So Dante entered the guild of physicians and apothecaries. In following years, his name is frequently found recorded as speaking or voting in the various councils of the republic. Education and poetry Not much is known about Dante's education, and it is presumed he studied at home. It is known that he studied Tuscan poetry, at a time when the Sicilian School (Scuola poetica Siciliana), a cultural group from Sicily, was becoming known in Tuscany. His interests brought him to discover the Occitan poetry of the troubadours and the Latin poetry of classical antiquity (with a particular devotion to Virgil). Florence and politics Dante, like most Florentines of his day, was embroiled in the Guelph-Ghibelline conflict. He fought in the battle of Campaldino (June 11, 1289), with the Florentine Guelphs against Arezzo Ghibellines, then in 1294 he was among the escorts of Charles Martel of Anjou (grandson of Charles I of Naples more commonly called Charles of Anjou) while he was in Florence. To further his political career, he became a pharmacist. He did not intend to actually practice as one, but a law issued in 1295 required that nobles who wanted public office had to be enrolled in one of the Corporazioni delle Arti e dei Mestieri, so Dante obtained admission to the apothecaries' guild. This profession was not entirely inapt, since at that time books were sold from apothecaries' shops. As a politician, he accomplished little, but he held various offices over a number of years in a city undergoing political unrest. |

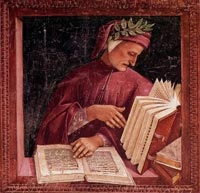

Profile portrait of Dante, by Sandro Botticelli Profile portrait of Dante, by Sandro Botticelli |

||

Andrea del Castagno, Dante Alighieri, from the Cycle of Famous Men and Women, (detail), c. 1450

|

|||

| Exile and death |

|||

| Boniface quickly dismissed the other delegates and asked Dante alone to remain in Rome. At the same time (November 1, 1301), Charles de Valois entered Florence with Black Guelphs, who in the next six days destroyed much of the city and killed many of their enemies. A new Black Guelph government was installed and Messer Cante de' Gabrielli da Gubbio was appointed Podestà of Florence. Dante was condemned to exile for two years, and ordered to pay a large fine. The poet was still in Rome, where the Pope had "suggested" he stay, and was therefore considered an absconder. He did not pay the fine, in part because he believed he was not guilty, and in part because all his assets in Florence had been seized by the Black Guelphs. He was condemned to perpetual exile, and if he returned to Florence without paying the fine, he could be burned at the stake. (The city council of Florence finally passed a motion rescinding Dante's sentence in June 2008.) He took part in several attempts by the White Guelphs to regain power, but these failed due to treachery. Dante, bitter at the treatment he received from his enemies, also grew disgusted with the infighting and ineffectiveness of his erstwhile allies, and vowed to become a party of one. Dante went to Verona as a guest of Bartolomeo I della Scala, then moved to Sarzana in Liguria. Later, he is supposed to have lived in Lucca with a lady called Gentucca, who made his stay comfortable (and was later gratefully mentioned in Purgatorio, XXIV, 37). Some speculative sources claim he visited Paris between 1308 and 1310 and others, even less trustworthy, take him to Oxford: these claims, first occurring in Boccacio's book on Dante several decades after his death, seem inspired by readers being impressed with the poet's wide learning and erudition. Evidently Dante's command of philosophy and his literary interests deepened in exile, when he was no longer busy with the day-to-day business of Florentine domestic politics, and this is evidenced in his prose writings in this period, but there is no real indication that he ever left Italy. In 1310, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII of Luxembourg, marched 5,000 troops into Italy. Dante saw in him a new Charlemagne who would restore the office of the Holy Roman Emperor to its former glory and also re-take Florence from the Black Guelphs. He wrote to Henry and several Italian princes, demanding that they destroy the Black Guelphs. Mixing religion and private concerns, he invoked the worst anger of God against his city, suggesting several particular targets that coincided with his personal enemies. It was during this time that he wrote De Monarchia, proposing a universal monarchy under Henry VII. [2] In 1312, Henry assaulted Florence and defeated the Black Guelphs, but there is no evidence that Dante was involved. Some say he refused to participate in the assault on his city by a foreigner; others suggest that he had become unpopular with the White Guelphs too and that any trace of his passage had carefully been removed. In 1313, Henry VII died (from fever), and with him any hope for Dante to see Florence again. He returned to Verona, where Cangrande I della Scala allowed him to live in a certain security and, presumably, in a fair amount of prosperity. Cangrande was admitted to Dante's Paradise (Paradiso, XVII, 76). |

Andrea del Castagno, Dante Alighieri, from the Cycle of Famous Men and Women, c. 1450. Detached fresco. 247 x 153 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze. The picture shows one of the three Tuscan poets represented in the cycle. |

||

| In 1315, Florence was forced by Uguccione della Faggiuola (the military officer controlling the town) to grant an amnesty to people in exile, including Dante. But Florence required that as well as paying a sum of money, these exiles would do public penance. Dante refused, preferring to remain in exile. When Uguccione defeated Florence, Dante's death sentence was commuted to house arrest, on condition that he go to Florence to swear that he would never enter the town again. Dante refused to go. His death sentence was confirmed and extended to his sons. Dante still hoped late in life that he might be invited back to Florence on honorable terms. For Dante, exile was nearly a form of death, stripping him of much of his identity and his heritage. He addresses the pain of exile in Paradiso, XVII (55-60), where Cacciaguida, his great-great-grandfather, warns him what to expect: |

|||

| ... Tu lascerai ogne cosa diletta ... più caramente; e questo è quello strale che l'arco de lo essilio pria saetta. Tu proverai sì come sa di sale lo pane altrui, e come è duro calle lo scendere e 'l salir per l'altrui scale ... |

You shall leave everything you love most: this is the arrow that the bow of exile shoots first. You are to know the bitter taste of others' bread, how salty it is, and know how hard a path it is for one who goes ascending and descending others' stairs ... |

||

As for the hope of returning to Florence, he describes it as if he had already accepted its impossibility, (Paradiso, XXV, 1–9): |

|||

| Se mai continga che 'l poema sacro al quale ha posto mano e cielo e terra, sì che m'ha fatto per molti anni macro, vinca la crudeltà che fuor mi serra del bello ovile ov'io dormi' agnello, nimico ai lupi che li danno guerra; con altra voce omai, con altro vello ritornerò poeta, e in sul fonte del mio battesmo prenderò 'l cappello ... |

If it ever come to pass that the sacred poem to which both heaven and earth have set their hand so as to have made me lean for many years should overcome the cruelty that bars me from the fair sheepfold where I slept as a lamb, an enemy to the wolves that make war on it, with another voice now and other fleece I shall return a poet and at the font of my baptism take the laurel crown ... |

||

|

|||

Prince Guido Novello da Polenta invited him to Ravenna in 1318, and he accepted. He finished the Paradiso, and died in 1321 (at the age of 56) while returning to Ravenna from a diplomatic mission to Venice, possibly of malaria contracted there. Dante was buried in Ravenna at the Church of San Pier Maggiore (later called San Francesco). Bernardo Bembo, praetor of Venice in 1483, took care of his remains by building a better tomb. |

|||

|

||

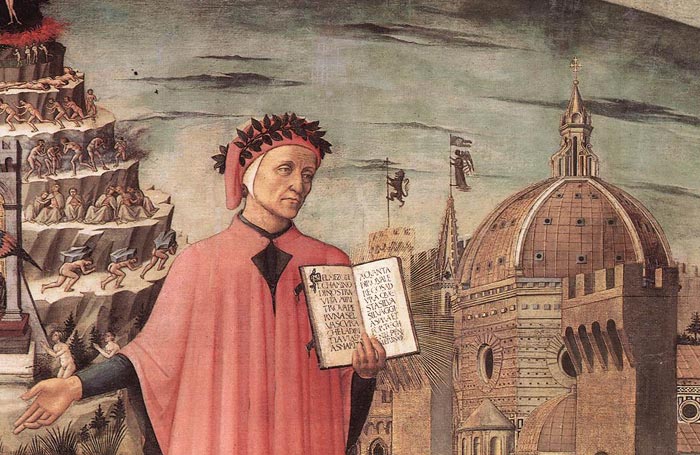

Domenico di Michelino, Dante and the Three Kingdoms, 1465, oil on canvas, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence |

||

| Works |

||

The Divine Comedy describes Dante's journey through Hell (Inferno), Purgatory (Purgatorio), and Paradise (Paradiso), guided first by the Roman poet Virgil and then by Beatrice, the subject of his love and of another of his works, La Vita Nuova. While the vision of Hell, the Inferno, is vivid for modern readers, the theological niceties presented in the other books require a certain amount of patience and knowledge to appreciate. Purgatorio, the most lyrical and human of the three, also has the most poets in it; Paradiso, the most heavily theological, has the most beautiful and ecstatic mystic passages in which Dante tries to describe what he confesses he is unable to convey (e.g., when Dante looks into the face of God: "all'alta fantasia qui mancò possa" - "at this high moment, ability failed my capacity to describe," Paradiso, XXXIII, 142).

By its serious purpose, its literary stature and the range - both stylistically and in subject matter - of its content, the Comedy soon became a cornerstone in the evolution of Italian as an established literary language. Dante was more aware than most earlier Italian writers of the variety of Italian dialects and of the need to create a literature beyond the limits of Latin writing at the time, and a unified literary language; in that sense he is a forerunner of the renaissance with its effort to create vernacular literature in competition with earlier classical writers. Dante's in-depth knowledge (within the realms of the time) of Roman antiquity and his evident admiration for some aspects of pagan Rome also point forward to the 15th century. Ironically, while he was widely honoured in the centuries after his death, the Comedy slipped out of fashion among men of letters: too medieval, too rough and tragical and not stylistically refined in the respects that the high and late renaissance came to demand of literature. He wrote the Comedy in a language he called "Italian", in some sense an amalgamated literary language mostly based on the regional dialect of Tuscany, with some elements of Latin and of the other regional dialects. [3] |

Dante, poised between the mountain of purgatory and the city of Florence, displays the famous incipit Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita in a detail of Domenico di Michelino's painting, Florence 1465 [1] |

|

Dante's other works include the Convivio ("The Banquet")[8] a collection of his longest poems with an (unfinished) allegorical commentary; Monarchia,[9] a summary treatise of political philosophy in Latin, which was condemned and burned after Dante's death[10][11] by the Papal Legate Bertrando del Poggetto, which argues for the necessity of a universal or global monarchy in order to establish universal peace in this life, and this monarchy's relationship to the Roman Catholic Church as guide to eternal peace; De vulgari eloquentia ("On the Eloquence of Vernacular"),[12] on vernacular literature, partly inspired by the Razos de trobar of Raimon Vidal de Bezaudun; and, La Vita Nuova ("The New Life"),[13] the story of his love for Beatrice Portinari, who also served as the ultimate symbol of salvation in the Comedy. The Vita Nuova contains many of Dante's love poems in Tuscan, which was not unprecedented; the vernacular had been regularly used for lyric works before, during all the thirteenth century. One of the most famous poems is Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare, which many Italians can recite by heart. However, Dante's commentary on his own work is also in the vernacular - both in the Vita Nuova and in the Convivio - instead of the Latin that was almost universally used. References to Divina Commedia are in the format (book, canto, verse), e.g., (Inferno, XV, 76). |

||

| In the 1480s, the great Florentine painter Sandro Botticelli was commissioned by Lorenzo de' Medici to illustrate Dante's Divine Comedy. Botticelli's genius as a pictorial narrator made him ideally suited to the commission and he followed the text meticulously, giving extraordinary visual form to the poet's epic tripartite journey through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. Executed on large sheets of sheepskin parchment, each extraordinarily delicate ink line drawing illustrates one canto or section of Dante's poem.

|

||

Dante imagined Hell as being an abyss with nine circles, which in turn divided into various rings. Botticelli's cross-section view of the underworld is drawn so finely and precisely that it is possible to trace the individual stops made by Dante and Virgil on their descent to the centre of the earth. Botticelli’s illustrations for the Divine Comedy were begun about a century and a half after Dante’s death. Between 1480 and 1495, the artist followed the poet canto by canto. Ninety-two of the drawings survived. Art in Tuscany | Sandro Botticelli | Illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy |

||

|

||

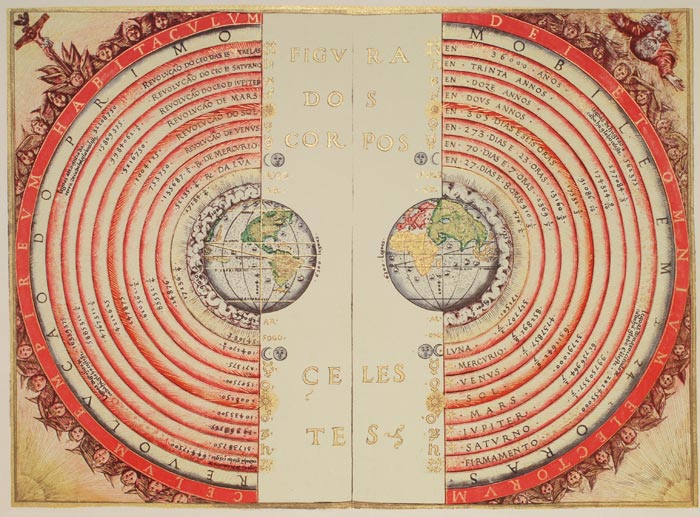

The Ptolemaic geocentric model of the Universe according to the Portuguese cosmographer and cartographer Bartolomeu Velho (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris). |

||

|

||||

Museo Casa di Dante | www.museocasadidante.it/ |

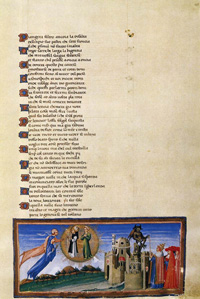

Several remarkable illustrated Dante manuscripts exist. To the codex in the British Library, London, Giovanni di Paolo created the magnificent pictures for the Paradiso section. The miniature of the Canto IX shows the city of Florence with Giotto's famous Bell tower at its centre. From one of its towers, a devil announces the offences of the Powerful of this world. On the left, Dante is lifted in the air by Beatrice and beholds the heroine of love, Cunizza of Treviso, who appears in an aura of light. Some initials in this manuscript are attributed to the Sienese fresco painter Vecchietta. |

|||

|

||||

Illustration of Dante's Paradiso, canto X, first circle of the 12 teachers of wisdom led by Thomas Aquinas Manuscript: British Library, Yates Thompson 36, fol. 147 (between 1442 and c.1450). Dante and Beatrice meet twelve wise men in the Sphere of the Sun (miniature by Giovanni di Paolo), Canto 10.

|

||||

|

||||

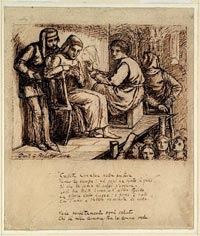

[4] Giotto is painting the portrait of Dante on a chapel wall, while Beatrice moves below in a procession of women. Cimabue is on the right. Six lines of Italian verse from Dante's Purgatorio, followed by the two opening lines of a sonnet from the Vita Nuova, are inscribed below the drawing.

|

||||

Works by Dante Alighieri | Wikipedia

|

||||

|

||||

A plaque in the Abbey of Vallombrosa commemorates a visit from Dante

|

||||

Beatrice, celebrated in the Vita Nuova and Commedia, is Dante's inspiration and spiritual guide in the later work. Dante's Beatrice is generally identified as Beatrice Portinari, the daughter of a banker and wife of Simone dei Bardi, who died at the age of 24. In the Comedy Beatrice is an image of absolute perfection and functions as an intermediary in Dante's ascent to God. Without Beatrice Dante's Comedy would not exist.

|

||||

|

||||

Monte Oliveto Maggiore abbey |

Abbey of Sant 'Antimo |

L'eremo di Montesiepi (the Hermitage of Montesiepi) |

||

This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Dante Alighieri and Sistine Chapel, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, December |

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montecristo |

||

The Villa Tommasi in Metelliano |

The Valle d'Ombrone and Castello Banfi |

Torre Alfina is a fraction of Acquapendente, a charming medieval village, located on the top of a hill of volcanic origin. | ||

|

|

|||

Florence, Duomo Santa Maria del Fiore |

Florence, Santa Croce |

Florence, Piazza della Repubblica |

||

| According to some legends, the beautiful Pia, Nello d'Inghiramo de Pannocchieschi's sorrowful wife, crossed this bridge to go into exile in Maremma, at Castello della Pietra. Dante Alighieri wrote about this legend (Divine Commedy, Purgatorio, Canto V). | ||||

"Oh, when you will have come back into the world And you will have rested from the long walk, follow the third spirit, after the second, remember me, I am Pia, born in Siena and died in Maremma. How I died, he, who first gave me his ring And then married me, knows." |

||||

|

||||

| View from Podere Santa Pia on the Marremma hills | ||||