|

Giovanni di Paolo,, The Entombment, 1426, tempera and gold leaf on panel, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland |

Giovanni di Paolo |

| Giovanni di Paolo di Grazia, one of the most important Italian painters of the 15th-century Sienese school. He is chiefly notable for carrying the brilliantly colourful vision of Sienese 14th-century paintings on into the Renaissance. His early works show the influence of previous Sienese masters, his landscapes and his figures still reverberate with echoes of Duccio's work, but his later style grew steadily more individualized, characterized by vigorous, harsh colors and elongated forms. His art most beautifully reflects the 15th-century artistic conservatism of a commercially declining city. Many of his works have an unusual dreamlike atmosphere, such as the surrealistic Saint Nicholas of Tolentino Saving a Ship (1455?, Philadelphia Museum of Art), while his last works - particularly Last Judgment, Heaven, and Hell (1465?) and Assumption of the Virgin (1475), both at Pinacoteca, Siena - are grotesque treatments of their lofty subjects. Giovanni's reputation declined after his death but was revived in the 20th century. |

||

The original Malavolti polyptych is Giovanni’s earliest known altarpiece, painted in 1426 when he was twenty-three, for the large church of San Domenico in Siena. Throughout his career he worked for the Dominican Order and its austerity may have encouraged his lifelong path toward an ever more mystical expressionism. In The Entombment, the shadow points up Nicodemus as the key figure who gave up his tomb for the burial of Jesus. This unusual act of charity may be a reflection of the Malavolti family’s commission of the altarpiece, and their relationship to the mendicant order. Throughout his career, Giovanni di Paolo referred to the pictorial tradition of his native Siena that was rooted in Byzantine art and is characterized by, in particular, the gold ground and the stylized rock formations. Art in Tuscany | Giovanni di Paolo | The Malavolti altarpiece |

|

|

Giovanni di Paolo was an independent artist who managed to thrive in a Siena which was on the one hand conservative and on the other responsive to such inventive minds as Sassetta and the Osservanza Master. Like these artists, Giovanni di Paolo had remarkable narrative gifts as an artist as is clear from such masterpieces as The Life of John the Baptist (Art Institute of Chicago), The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden (Robert Lehman Collection, Metropolitan Museum, New York) and the Paradise (Metropolitan Museum, New York). His early training seems to have included contact with Lombard artists (his earliest patron was the Lombard Anna Castiglione a relative of Cardinal Castiglione Branda, patron of Vecchietta) and probably French artists too. He could, for example, have known the Limbourg brothers, the Franco-Flemish illuminators who were in Siena in 1413. Certainly the nervous, staccato quality of line that distinguishes his work from that of his Sienese contemporaries betrays an assimilation of Lombard and French Gothic forms. By the mid 1420s Giovanni di Paolo's career was flourishing and from that period come the Pecci and Branchini altarpieces (Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena and Norton Simon Museum, San Marino) which both show the influence of Gentile da Fabriano who had painted a (now lost) altarpiece in 1425/6 for the Sienese Notaries Guild. |

||

| Giovanni di Paolo's brilliant color and pattern were typically Sienese, but he is distinguished from his teachers and contemporaries by an expressive imagination. His unique style is otherworldly and spiritual. Here the drama is heightened by a dark background and contrasting colors, nervous patterns, and unreal proportions. In the center, Gabriel brings news of Christ's future birth to the Virgin. Thus is put in motion the promise of salvation for humankind, a salvation necessitated by the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, which we see happening on the left, outside Mary's jewellike home. Mary will reopen the doors of Paradise closed by Eve's sin. The scene of Joseph warming himself in front of a fire, on the right, is an unusual addition. Perhaps it refers simply to the season of Jesus' birth, but more likely it is layered with other meanings, suggesting the flames of hope and charity and invoking the winter of sin now to be replaced by the spring of this new era of Grace. The three scenes help make explicit the connection between the Fall and God's promise of salvation, which is fulfilled at the moment of the Annunication. Though Giovanni's primary concern is not the appearance of the natural world, it is clear that he was aware of contemporary developments in the realistic depiction of space. Note how the floor tiles appear to recede, a technique adopted by Florentine artists experimenting with the new science of perspective. Art in Tuscany | Giovanni di Paolo | The Annunciation and Expulsion from Paradise |

The Annunciation and Expulsion from Paradise, circa 1435, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. |

|||

|

||||

| Giovanni di Paolo, The Creation and the Expulsion from the Paradise, c. 1445, tempera and gold on wood, 46, 4 x 52,1 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

||||

| This extraordinary panel is widely admired for its brilliant colours, curious iconography, and mystical vitality At the left, God the Father, supported by 12 blue cherubim, flies downward, pointing with his right hand at a circular "mappamondo", which fills the lower half of the scene. The representation of earth is surrounded by concentric circles, including a green ring (for water), a blue ring (for air), a red ring (for fire), the circles of the seven planets, and the circle of the Zodiac. On the right, in a separate scene set in a meadow filled with flowers, Adam and Eve walk to the right against a line of seven trees with golden fruit. Their heads turn back toward a naked angel, who expels them from Paradise. Below them spring the four rivers of Paradise, which extend to the base of the picture. This panel is a fragment from the predella of an altarpiece painted for the church of San Domenico in Siena and now in the Uffizi in Florence. Another panel from the same predella is also in the Museum's collection. The influence of the International Gothic style, especially French miniature painting, can be seen in the figures of the angel, Adam, and Eve, and in the details of flora and fauna. Art in Tuscany | Giovanni di Paolo, The Creation and the Expulsion from the Paradise |

||||

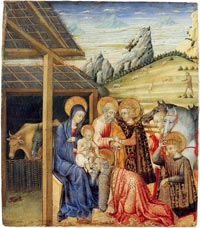

| The Adoration of the Magi takes place high in the mountains; the figures derive from Gentile da Fabriano's courtly magi, though a more intimate note is struck when the young King reassures the ever-bewildered Joseph, placing an arm around his shoulders and tenderly taking his hand. Behind the green alpine meadow and its calm pastoral air, however, we plunge suddenly down onto a patchwork plain of almost infinite extension - a quilt of palest blue and khaki, merging with the feathery sky, and painted with an atmospheric touch so delicate and limpid that it challenges the work of his great Venetian contemporaries. Giovanni di Paolo's brilliant color and pattern were typically Sienese, but he is distinguished from his teachers and contemporaries by an expressive imagination. His unique style is otherworldly and spiritual. Though Giovanni's primary concern is not the appearance of the natural world, it is clear that he was aware of contemporary developments in the realistic depiction of space. Art in Tuscany | Giovanni di Paolo, Adoration of the Magi, about 1450-1460 |

Giovanni di Paolo, Adoration of the Magi, about 1450-1460, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|||

In the mid-1460s Pope Pius II commissioned four of Siena's leading painters to execute altarpieces for his newly completed cathedral in Pienza. These were the two slightly older painters Sano di Pietro and Giovanni di Paolo, the tried and tested Vecchietta, and a younger painter, Matteo di Giovanni. Each of the four painters executed an altarpiece whose form and subject matter appears to have been closely controlled by their humanist patron. |

||||

| The Virgin of the Assumption with Saints 1462-63 Tempera on panel, 280 x 225 cm Cathedral, Pienza |

||||

|

||||

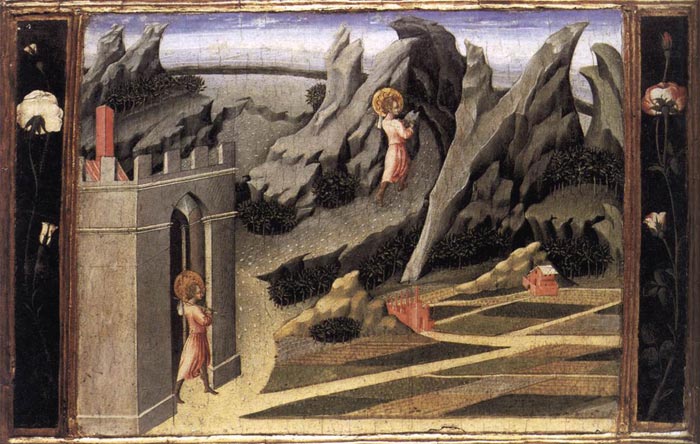

Giovanni di Paolo, Saint John the Baptist retiring to the Desert from Baptist Predella, 1454, The National Gallery, London |

||||

| Together with Sassetta, Giovanni di Paolo was one of the leading Sienese painters in the fifteenth century. So strong was the hold on Sienese art of its great fourteenth-century masters - Duccio and his followers - that both Giovanni di Paolo and Sassetta consistently harked back to earlier models.

Giovanni's dual allegiance to the modern and the old can clearly be seen in the four predella panels of Scenes from the Life of Saint John the Baptist at the National Gallery in London, of which Saint John retiring to the Desert is likely to have been the second from the left. The other panels represent the saint's birth, the Baptism of Christ, and the Feast of Herod at which Salome's dance and Herod's reward for it brought about the decapitation of the saint. The story of Saint John the Baptist is told in the Gospels and in legend, and its pictorial tradition was well established by the fifteenth century. The altarpiece of which these panels formed the predella - a box-like supporting element for the main painting - was a large Madonna and Saints perhaps painted for the church of Sant'Agostino in Siena (now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York). This scene shows the Baptist as a child, carrying his few needs on his shoulder, leaving the familiar city gate to make his way up into the wilderness. Just to his right we see him again, several miles away, but not reduced at all in scale: a giant walking up the steep mountain path. The head and torso of the two figures are almost identical, but as John climbs he slings his bundle over the other shoulder. Thus the spectator has moved with St John, and the foreground landscape becomes the vista opening up below as the child climbs. The picture is about renouncing the city, leaving behind the man-made grid of cultivated fields, its beautiful patchwork of contrasted greens, for a world of wilder forms. Higher up, we glimpse a yet further region - a blue-and-white ice realm, across a dark river, extending to the curved rim of the horizon - all laid in with a scintillating economy of mark. Charming are the borders of roses painted entirely realistically on either side. Curiously, these are seen from below, as by a viewer at eye level with the lower bud on each branch. |

||||

|

|

|

||

| The Head of Saint John the Baptist Brought before Herod, 1455/60 [4] |

Saint John the Baptist in Prison Visited by Two Disciples [4] |

The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist [4] | ||

|

||||

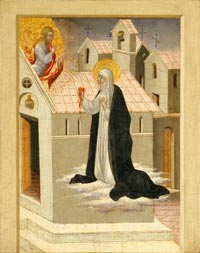

| Catherine Benincasa was born in Siena in about 1347, died in 1380, and was canonized in 1461. She was a member of the Dominican order, a mystic, and minister to the poor and plague-stricken. A biography of Saint Catherine was written by her confessor, Raymond of Capua. In this scene, Catherine is shown elevated in rapture against a background of several churches. She holds out her heart to Christ, who appears above her, his hand raised in blessing.

The panel St Catherine Exchanging her Heart with Christ is from a series of ten scenes from the life of Saint Catherine of Siena. Giovanni di Paolo was already in his mid-sixties when he embarked on ten scenes from the Life of St Catherine, commissioned by the Hospital immediately after the Sienese Pope Pius II had secured her controversial canonization in 1461. Giovanni would have known her story intimately: working at San Domenico as a young man, he must have met many of her surviving friends and followers. Catherine had prayed to Christ to give her a new, pure heart. A few days later, 'elevated in rapture... her heart leapt out of her body, entered Christ's side, and was made one with his heart'. Here, Catherine levitates outside her greenish grey convent with its pink roofs; the operation is under way, as she holds her left hand to her bosom, and stretches forth her right, her scarlet heart spurting blood. Christ rears up behind his own image as the Man of Sorrows above the open church door.[1]

|

||||

| Giovanni's brilliant color and pattern were typically Sienese, but he is distinguished from his teachers and contemporaries by an expressive imagination. His unique style is otherworldly and spiritual. Here the drama is heightened by a dark background and contrasting colors, nervous patterns, and unreal proportions. In the center, Gabriel brings news of Christ's future birth to the Virgin. Thus is put in motion the promise of salvation for humankind, a salvation necessitated by the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, which we see happening on the left, outside Mary's jewellike home. Mary will reopen the doors of Paradise closed by Eve's sin. The scene of Joseph warming himself in front of a fire, on the right, is an unusual addition. Perhaps it refers simply to the season of Jesus' birth, but more likely it is layered with other meanings, suggesting the flames of hope and charity and invoking the winter of sin now to be replaced by the spring of this new era of Grace. The three scenes help make explicit the connection between the Fall and God's promise of salvation, which is fulfilled at the moment of the Annunication.

Though Giovanni's primary concern is not the appearance of the natural world, it is clear that he was aware of contemporary developments in the realistic depiction of space. Note how the floor tiles appear to recede, a technique adopted by Florentine artists experimenting with the new science of perspective. |

||||

| Giovanni di Paolo produced not only numerous large altarpieces and small devotional panels, such as The Annunciation and Expulsion from Paradise and The Adoration of the Magi, but also a range of manuscript illumination, including grand choir books and a volume of Dante’s Divine Comedy. The Initial A on view, cut from a gradual, illustrates Psalm 24, a prayer for protection from enemies. David, appearing old and frail, with his hands raised in desperation, now looks for deliverance from the Lord. This solemn event stands in stark contrast to the initial itself: a powerful winged dragon gives the letter form even as the beast devours part of it. This inventive initial in the form of a voracious winged dragon was the first, and probably the largest, in the choir book. Within the letter, King David kneels as the Lord raises his hand in blessing. The initial's subject was inspired by the text of the chant it introduces. The chant is taken from Psalm 24 which includes the lines, "He that hath clean hands and a pure heart; who hath not lifted up his soul onto vanity, nor sworn deceitfully. He shall receive the blessing from the Lord..."[2] |

Giovanni di Paolo, Detail of The Beheading of St. John the Baptist, The Art Institute of Chicago, ca. 1455-60Siena, c. 1440 cutting from a gradual, Cutting: 20 x 18.6 cm (7 7/8 x 7 5/16 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

|||

| The account books of the most important offices of Siena's medieval municipality had covers made of decorated wooden panels. These were called 'bicherne', named after Bicherna, the financial office that started decorating its manuscripts before any other office did and continued to do so extensively. Production of these decorated book covers started in 1257 and continued until the middle of the fifteenth century. This strange alliance between art and bureaucracy is one of the most original manifestations of Sienese art and involved some of the finest artists.[3]

This Annunciation panel comes from the Gabella Generale (general tax office). It shows the Virgin Mary, seated on a chest with her hands joined in prayer and wrapped in a voluminous cloak. The Archangel Gabriel stands before her with his arms crossed and holding an olive branch in one hand, symbolizing peace. In the middle of the painting, between the figures of Mary and the archangel, is a finely worked vase holding a bunch of lilies. They symbolize Mary's purity and virginity. Above the vase, God's blessing hand sends out rays of light that carry the dove of the Holy Spirit toward Mary. |

|

|||

| Castiglione d'Orcia marks the boundary between Val d'Orcia and the Monte Amiata and was a strategic defence point for the old Via Francigena. Rocca d'Orcia is nearby and worthy of a mention with its impressive fortified tower.

Sala d'Arte San Giovanni, (Via San Giovanni 10), housed in the former residence of the religious brotherhood of the same name, holds paintings by some of the major representatives of the Sienese school: Simone Martini, Lorenzo di Pietro known as Il Vecchietta and Giovanni di Paolo. |

|

|||

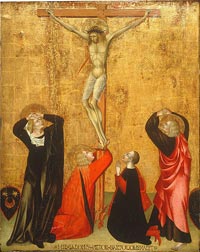

The city-state of Siena, a large Italian hill town some 70km south of Florence, had its golden age in the early trecentro under the artistic genius of Duccio (c.1260–1319) and Simone Martini (c.1285–1344). They developed a rich courtly style dependent on a dancing line rather than the naturalistic concerns of Florentine painters such as Giotto. Giovanni di Paolo’s Crucifixion pays homage to this legacy, to which he was bound by a continuous workshop tradition. The stylised scalloping of the figures’ cascading drapery is a hallmark of this regional inheritance. The artist seems to have been enormously popular in his own lifetime and over two hundred generally-accepted autograph works survive.

|

||||

|

|||||

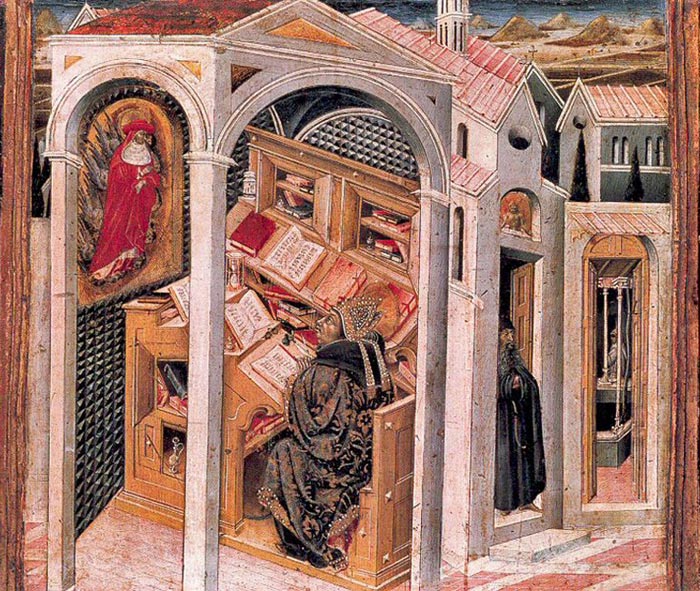

Giovanni di Paolo, St Jerome Appearing to St Augustine, c. 1456, Staatliche Museen, Berlin |

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Illustration of Dante's Paradiso, canto X, first circle of the 12 teachers of wisdom led by Thomas Aquinas Manuscript Manuscript: British Library, Yates Thompson 36, fol. 147 (between 1442 and c.1450). Dante and Beatrice meet twelve wise men in the Sphere of the Sun (miniature by Giovanni di Paolo), Canto 10. Paradiso (Italian for "Paradise" or "Heaven") is the third and final part of Dante's Divine Comedy, following the Inferno and the Purgatorio. It is an allegory telling of Dante's journey through Heaven, guided by Beatrice, who symbolises theology. In the poem, Paradise is depicted as a series of concentric spheres surrounding the earth, consisting of the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the Fixed Stars, the Primum Mobile and finally, the Empyrean. It was written in the early 14th century. |

|||||

| Sassetta: The Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece, by Machtelt Israels (Editor), James R. Banker (Contributions by), Rachel Billinge (Contributions by), Roberto Bellucci (Contributions by), 2009, Florence & Leiden, Villa I Tatti/ The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies/ Primavera Press. British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts | Dante Alighieri | Divina Commedia, between 1444 and c. 1450 | Inferno and Purgatorio (ff. 1-128), and all historiated initials illuminated by Priamo della Quercia between 1442 and 1450 (previously attributed to Lorenzo Vecchietta; Paradiso (ff. 129-190v) illuminated by Giovanni di Paolo c. 1450. John Wyndham Pope-Hennessy, Paradiso: The Illuminations to Dante's Divine Comedy by Giovanni Di Paolo, New York, Random House, 1993. Dante's Divine Comedy has inspired artists from Giotto down to the present. Perhaps among the most beautiful illustrations are those of the 15th-century Sienese painter Giovanni di Paolo, who illuminated a Paradiso manuscript for the library of the King of Naples, now in the British Library as Yates-Thompson MS 36. Pope-Hennessy, the noted British art historian, presents reproductions of di Paolo's 61 illuminations in a large format and in full color. He includes a lucid historical introduction and a commentary on the content of each of the miniatures. The book also includes Charles Singleton's prose translation of the Paradiso . H. W. van Os, Giovanni di Paolo's Pizzicaiuolo Altarpiece, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Sep., 1971), pp. 289-302

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Podere Santa Pia, an ancient small cloister, faces the gentle hills of Maremma Region, a place always admired for its views and its surrounding landscape. Santa Pia offers its guests a breathtaking view over the Maremma hills. On clear days or evening, one can even see Corsica. | |||||

|

|||||