|

| Guidoccio di Giovanni Cozzarelli, The Legend of Cloelia (detail), ca. 1480, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Guidoccio di Giovanni Cozzarelli |

Guidoccio (di Giovanni) Cozzarelli (b Siena, 1450; d Siena, 1516-17) was aainter and illuminator. He trained in the workshop of Matteo di Giovanni, with whom he was associated from about 1470 to 1483 and with whom he is often confused. Early illuminations for the Antiphonals of Siena Cathedral and a number of securely attributed paintings demonstrate Guidoccio's development of a fine, distinctive style that reflects Tuscan and northern European as well as Sienese influences. A scene from an Antiphonal depicting a Religious Ceremony (Siena, Bib. Piccolomini), a fragment of an altarpiece depicting the Annunciation and the Journey to Bethlehem and a cassone panel depicting the Legend of Cloelia all combine masses of rusticated and Classical architectural structures into perspective vistas. The dense cityscapes are played off against open sky and landscape, while porticos, gateways and vaulted spaces form the stage on which tactile and sprightly figures re-enact religious drama or ancient legends. In the Baptism of Christ with SS Jerome and Augustine the deep, panoramic landscape and triad of angels suggest Umbrian influences. A connection with Piero della Francesca through Matteo di Giovanni is possible.

|

Guidoccio Cozzarelli's greatness derives from eclecticism and the spirit of humanity that saturate his paintings. Cozzarelli's historical works possess a passionate exuberance, bursting with dramatic details. His energetic style generated steady lucrative commissions throughout his painting career. He is considered one the greatest Renaissance painters of all time. |

||

The Legend of Cloelia, ca. 1480 |

||

|

||

Guidoccio di Giovanni Cozzarelli, The Legend of Cloelia, ca. 1480, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

||

| During the early fifteenth century, Europe continued to evolve out of a series of medieval feudal states ruled by wealthy landowners into concentrated town centers or cities functioning as powerful economic nuclei. As these cities took on greater political and financial authority, the middle classes, made up of artisans, bankers, and merchants, played more substantial roles in commerce with their greater wealth and independence. Along with this prosperity, particularly marked in Italy, an increased number of palaces and villas were constructed, subsequently creating a greater demand for extravagant furniture and domestic art, both for established aristocratic patrons and the newly wealthy. (...) The manufacture of secular art objects, usually for the purpose of commemoration, personalized these lavish Italian Renaissance interiors. Because childbirth and marriage were richly celebrated, a number of objects were made in honor of these rituals. The wooden birth tray, or desco da parto, played a utilitarian as well as celebratory role in commemorating a child's birth. It was covered with a special cloth to function as a service tray for the mother during confinement and later displayed on the wall as a memento of the special occasion. A desco da parto was usually painted with mythological, classical, or literary themes, as well as scenes of domesticity. The reverse often displayed a family crest. In some cases, a birth tray was purchased already painted, but custom-decorated with heraldry that personalized what might otherwise be a line item from a shop. The Legend of Cloelia Cloelia was one of ten daughters and ten sons of Roman nobility who were given as hostages by the Roman consul Publicola to the Etruscan king Lars Porsena, as a token of good faith following the conclusion of a treaty between the Romans and the Etruscans. Cloelia led an escape by crossing the Tiber river on horseback and persuading her female companions to swim after her. Publicola returned the girls to the Etruscans, but Porsena, in admiration of Cloelia's courage, presented her with a horse, and freed her and some of her companions. The story of Cloelia is recounted by Plutarch ("Life of Publicola," XIX). This painting depicts the girls swimming across the Tiber in the center and arriving at the gate of Rome on the right. At the left Publicola returns them to the Etruscan camp and Cloelia kneels before Porsena. |

||

|

||

|

||

Guidoccio di Giovanni Cozzarelli, The Legend of Cloelia (detail), ca. 1480, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

||

The Annunciation and the Journey to Bethlehem |

||

The Annunciation and the Journey to Bethlehem, ca. 1480-1490 |

||

| The Annunciation and the Journey to Bethlehem originally formed the upper right-hand corner of a large altarpiece, the exact format of which is unknown. The two scenes were part of the series illustrating either the infancy of Christ or the life of the Virgin, which may have served as the backdrop to an image of the Madonna and Child Enthroned; in that case, the cornice and pilaster at the far left of the panel may have been part of the Virgin’s throne. However, it is more likely that the foreground of the picture was occupied by a scene of the Nativity. This is suggested by the lower edge of the classical entablature, which, before it was partially repainted by an overzealous restorer, appeared as a ruin. The works of Cozzarelli, a painter of miniatures, altarpieces, and cassone panels (secular paintings used to decorate furniture), are frequently confused with those of his presumed master, Matteo di Giovanni (active 1452-1495). The format of Cozzarelli’s paintings and his feeling for decorative detail and textural richness are in the Sienese stylistic tradition, but his interest in perspective, naturalistic movement, classical architecture, and antique ornamentation reflects the significant influence of contemporary Florentine art. | ||

|

||

Guidoccio Cozzarelli, The Baptism of Christ, 1486 |

||

| Sienese Biccherna Covers |

||

Biccherne are painted biccherna tablets, originally book covers of the ledgers of the biccherna and gabella, the financial and fiscal offices of the commune of Siena. The panel The Virgin guiding “the ship of the Republic” refers to the return to Siena of the magistracy of the Nine lead by Pandolfo Petrucci, who later became Siena’s ruler, as a welcome change occurred under the Virgin’s protection. Traditionally attributed to Guidoccio Cozzarelli it was presented at the National Gallery exhibition in London as a work of Guidoccio’s master Matteo di Giovanni. |

||

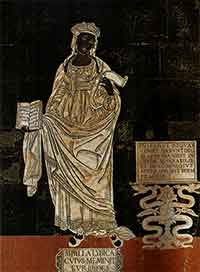

Siena, Duomo | Guidoccio Cozzarelli, Sibilla Libica |

||

|

||

Guidoccio Cozzarelli, Libyan Sibyl, mosaic floor (detail) 148, Siena, Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, left nave |

||

| Of the numerous masterpieces enclosed in the Cathedral of Siena, one of the most exceptional is certainly its floor. The inlaid marble mosaic floor of Siena's Cathedral is one of the most ornate of its kind in Italy, covering the whole floor of the cathedral. This undertaking went on from the 14th to the 16th centuries, and about forty artists made their contribution. According to 16th century artist and biographer Giorgio Vasari, Sienese master Duccio di Buoninsegna first designed the floor mosaics in the early 1300s. The panels are rectangles, rounds, hexagons, squares and rhombuses. The cartoons would be made on paper first by prominent local artists (or in one special case, by Umbrian master Pinturicchio), then they would be translated to marble mosaic format by stone cutting, carving and marquetry masters. The earliest panels were made using the graffito technique where lines were scratched into the surface of white marble and then filled with pitch or bitumen to make them black. Later panels used different colors of marble to create intricate inlays complete with delicate shading and strong chiaroscuro contrasts. The earliest panels are the Wheel of Fortune (1372), the Sienese She-Wolf Surrounded by the Emblems of Allied Cities (1373) and the Imperial Eagle (1374). In the 1480s, the 10 Sibyls were created and two large transept panels with shockingly vivid images of The Slaughter of the Innocents and The Expulsion of Herod.[2] In 1480 Alberto Aringhieri was appointed superintendent of the works. From then on, the mosaic floor scheme began to make serious progress. Between 1481 and 1483 the ten panels of the Sibyls were worked out. A few are ascribed to eminent artists, such as Matteo di Giovanni (The Samian Sibyl), Neroccio di Bartolomeo de' Landi (Hellespontine Sibyl) and Benvenuto di Giovanni (Albunenan Sibyl). The Cumaean, Delphic, Persian and Phrygian Sibyls are from the hand of the obscure German artist Vito di Marco. The Erythraean Sibyl was originally by Antonio Federighi, the Libyan Sibyl by the painter Guidoccio Cozzarelli, but both have been extensively renovated. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia is situated in a very panoramic and tranquil position, with spectacular views over Monte Argentario |

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Siena, Piazza del Campo |

Cypress trees between San Quirico d'Orcia and Montalcino, one of the bird trapping techniques to capture wild birds. |

||

|

|

|||

| The towers of San Gimignano | Montalcino |

Siena, Duomo |

||

Bagni San Filippo |

Pienza |

The Val d'Orcia and the Crete Senesi |

||

|

||||

| This holiday home offers its guests a breathtaking view over the Maremma hills. On clear days or evening, one can even see Corsica. | ||||