|

| |

Berlinghiero Berlinghieri |

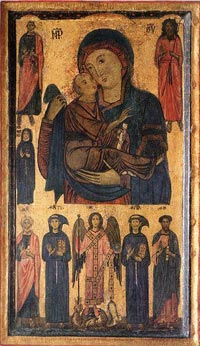

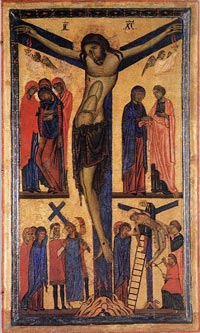

| Until the late eleventh century, southern Italy occupied the western border of the vast Byzantine empire. Even after this area fell under Norman rule in about 1071, Italy maintained a strong link with Byzantium through trade, and this link was expressed in the art of the period. Large illustrated Bibles ("giant Bibles") and Exultet Rolls—liturgical scrolls containing texts for the celebration of Easter, produced in the Benevento region of southern Italy—enjoyed great popularity from about 1050 onward. Miniature illustrations in the Bibles, which relate to contemporary monumental wall paintings produced in Rome, were strongly influenced by early Christian painting cycles from Roman churches. Berlinghiero Berlinghieri and his sons Bonaventura Berlinghieri (active 1228 – 74 ), Barone (active 1228 – 82 ), and Marco (active 1232 – 59 ). [1] A family of Lucchese painters whose vigorously linear Romanesque idiom is often erroneously described as a Byzantine manner, reflecting its debt to Byzantine conventions. The static figures, devoid of contrapposto and with out-of-scale heads, on the Crucifix signed by Berlinghiero (Lucca, Mus. Nazionale di Villa Guinigi) would have been quite unacceptable to Byzantine patrons, but its imposing drawing undoubtedly influenced later pictorial technique in Tuscany. His son Bonaventura signed the most important early panel of S. Francis and his Life ( 1235 ; Pescia, S. Francesco), whose two-dimensional settings caricature Byzantine pictorial space, but with a vigorous chiaroscuro. Marco illuminated a Lucchese Bible in 1150 (probably Lucca, Bib. Capit., cod. 1) and was in Bologna, 1253 – 9 , where the mural of the Massacre of the Innocents in S. Stefano shows a related Italo-Byzantine idiom. The family workshop is also credited with an important mosaic of Christ and the Apostles on the façade of S. Frediano, Lucca, epitomizing their influence on painting in Tuscany between 1225 and 1275. The Berlinghieri family exerted considerable influence on Florentine painting before Cimabue. Berlinghiero Berlinghieri, also known as Berlinghiero of Lucca, (fl. 1228 – before 1236) was an Italian painter of the early thirteenth century. He was the father of the painters Barone Berlinghieri, Bonaventura Berlinghieri, and Marco Berlinghieri. His actual name is unknown, as he is only known from the inscription Berlingerius me pinxit on the crucifix which is the basis of attributing other works to him.The Madonna and Child — of exceptional beauty and importance — is one of only two that can be confidently assigned to him on the basis of comparison with a signed crucifix. Berlinghiero was always open to Byzantine influence, and this Madonna is of the Byzantine type known as the Hodegetria, in which the Madonna points to the Child as the way to salvation. |

| After the sack of Constantinople in 1204 by Christian armies of the Fourth Crusade, precious objects from Byzantium made their way to Italian soil and profoundly influenced the art produced there, especially the brightly colored gold-ground panels that proliferated during the thirteenth century. A Madonna and Child by Berlinghiero, the foremost painter of the period working in the Tuscan city of Lucca, is one such example: in this panel, the Madonna gestures solemnly toward the infant Christ, depicted as a miniature adult, who wears a philosopher's robes and gestures in blessing. This composition is of the Byzantine type known as the Hodegetria, which may be translated as "One Who Shows the Way," as the Madonna points to Christ as the way to salvation. Starburst-like ornaments at the crown of the Madonna's head and on her right shoulder (a third would have appeared on her left shoulder, here concealed by the figure of Christ) are also traditional Byzantine motifs, symbolizing Mary's virginity before, during, and after the birth of Christ. |  |

|

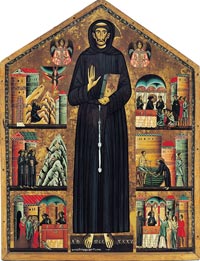

| Bonaventura Berlinghieri was known for his poignant and detailed scenes from the life of St. Francis on the predella (base of the altarpiece) of the Church of San Francesco at Pescia. The painting of St Francis is one of the earliest altarpieces dedicated to the saint who was canonized in 1228. Bonaventura was the son of the painter Berlinghiero of the Berlinghieri family of Lombardian painters. His presence at Lucca from 1232 to 1274 is confirmed by a long series of documents, of which one (1244) records that he undertook the entire decoration (untraced) of the deceased Archdeacon’s room. It was to include bird and other ornamental motifs, according to the wishes of Lombardo, master of works at Lucca Cathedral. The Pescia work is one of the earliest known pictorial narratives of the saint of Assisi. Consisting of a central panel and subsidiary scenes, it shows evidence of Byzantine influence.Another work of rare charm is his “St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata,” to be found in the Academy at Florence. Other works attributed to Bonaventura are not well documented. The Scenes from the Life of St Francis in Sta Croce, Florence, and the St Francis receiving the Stigmata in the Accademia, Florence, have also been attributed to him. |

||

| The early- and mid-thirteenth century produced a significant number of panel paintings of the life of Francis. Here I will only briefly comment on the earliest panel, signed by Bonaventura Berlinghieri and dated 1235 (a detail showing the stigmatization scene is in fig. 2). 26 This painting, done for the church of San Francesco in Pescia, contains six scenes from the life of Francis, including the first known paintings of Francis preaching to the birds and receiving the stigmata. The background of the stigmata scene contains the hermitage mentioned in Thomas, but the physical surroundings are those of a mountainside. It is possible that Berlinghieri knew that Alverna was a mountain, but, more likely, the depiction of Francis on a mountainside was used to convey deep symbolic significance. Three crucial events in Christ's life took place on mountains: the Transfiguration on Mt. Tabor, the Agony in the Garden on the Mount of Olives, and the Crucifixion on Mt. Calvary. References to all three of these events were implicitly, and sometimes explicitly, incorporated into the paintings of Francis receiving the stigmata. In this case, I believe that I can show that the most obvious reference is to the Mount of Olives. The seraph is depicted as described in Thomas, his wings red and brown, but he is not fixed to a cross. He is looking straight ahead, not down at Francis, and there is no real interaction or even emotional connection between the seraph and Francis. However, a viewer who did not know the details of the story would have to have concluded that the appearance of the seraph and the receiving of the stigmata were contemporaneous, since Berlinghieri has telescoped the two separate scenes without giving any indication that they were temporally distinct. This simultaneous depiction of the seraph and Francis, the mountainside, and even Francis's praying posture makes this scene an unmistakable iconographical reference to Christ's Agony in the Garden. A thirteenth-century viewer of this painting would have easily made this reference, recognizing the adaptation of this scene to the Agony in the Garden as specifically narrated by Luke. In the Lucan account, when Jesus goes to the Mount of Olives to pray to his Father, he is described as "having knelt down and prayed" and "then there appeared an angel from heaven to strengthen him"; finally, "gripped by anguish he prayed more intensely; and his sweat became like drops of blood that fell to the ground" (Luke 22:41-44). 27 Thus Francis kneeling and praying on a mountainside when an angel appears to him, followed by an extraordinary physical transformation, directly evokes this scene in Jesus' life that occurs immediately before his betrayal, arrest, and crucifixion. 28 Moreover, Francis is not standing in this scene. His prayer gesture, kneeling with hands (almost) joined, is a posture that was not common until the thirteenth century. 29 The primary meaning of the joined hands, of recollection and of offering oneself in concentrated surrender to God, especially in conjunction with kneeling, was used to express intense devotion to the presence of Christ in the Eucharist. [4] | ||

Bonaventura Berlinghieri, stigmatization scene from Francis of Assisi (detail from upper left), 1235, wood panel painting, church of San Francesco, Pescia. |

||

|

||||

[1] All three sons of Berlinghiero Berlinghieri became painters. Besides those for the best known, Bonaventura Berlinghieri, records survive concerning Barone di Berlinghiero ( fl 1228–82), probably the oldest of the brothers, and Marco di Berlinghiero ( fl 1232–55), and a detailed document of 1266 records Bonaventura’s stepson and apprentice, Lupardo di Benincasa (d Kingdom of Sicily, before 1258), who from c. 1249 worked independently and later moved to Sardinia. Barone is already mentioned in 1228, together with Berlinghiero and Bonaventura, in a list of Lucchese citizens. In 1243 he painted a panel for the Archdeacon of Lucca, by 1256 he had delivered a painted Crucifix to the parish church of Casabasciana, near Lucca, and in 1282 he undertook to paint a Crucifix, a Virgin and a St Andrew for the prior of S Andrea, Lucca. More is known of Marco, from records in Lucca from the 1230s. Probably the youngest of the brothers since he is not mentioned in the document of 1228, according to Garrison (1957) he is the ‘Marcus Pictor’ who in 1240 decorated a Sacramentary (London, BL, Egerton MS. 3036) for the monastery at Camaldoli, near Arezzo. Two documents of 1250 concern the decoration of a Bible (Lucca, Bib. Capitolare, MS. 1) for Alamanno, rector of the hospital of S Martino at Lucca. Marco has also been identified with the ‘Marcus pictor de Luca’ who in 1255 was paid for a painting (untraced) in the chapel of the Palazzo del Podestà in Bologna, and he is ascribed a fresco representing the Massacre of the Innocents (Bologna, S Sepolcro). These works reveal an artist closer to Bonaventura than to Berlinghiero. The the Berlinghieri were influenced by the new wave of Byzantinism which reached the peninsula after the capture of Constantinople by the crusaders. The painting in the Uffizi, The Crucifixion - Madonna and child with Saints, is a work attributed to the School of Bonaventura Berlinghieri, probably painted between 1260 and 1270. It comes from the Berlinghieri workshoprepresents one of the earliest surviving examples of the 'Eleusa' Virgin, the 'Affectionate Mother', an iconographic model that was first used for portable household altars although it subsequently became increasingly po[ular and widespread until the end of the fourteenth century, being well suited to the emotional tendency expressed by Gothic art. Bonaventura Berlinghieri instils a liveliness into the figures and objects with a refined, almost miniaturist technique. There is, however, a clear reference to Byzantine models which allow the artist to express his lyrical mysticism. The painting comes probably from the workshop of Berlinghieri and it is dated variously to the second half of the 13th century. The Master of the Bardi of Saint Francis was a Florentine artist named for a large panel on the altar of the Capella Badri in the Basilica di Santa Croce in Florence. In the Uffizi Gallery is also, Saint Francis Receives the Stigmata, and the artist has been given the attribution of the work, The Crucifix with eight stories from the Passion. Though this claim has been met with some reservation from critics who claim two separate artists had worked on the Saint Francis panels, and that The Crucifix piece may not have been created by either of them. (The Grove Dictionary of Art) The works nonetheless share a Byzantine influence among other similar qualities to imply they are created by the same master. Vasari had claimed the work depicting Saint Francis was by Cimabue (1240 – 1302), who had executed other known works in the Santa Croce. Though most critics agree that while the work has Florentine qualities, and was completed before Giotto’s time (hence Cimabue), it is more closely associated to the Luccan School of the Berlinghieri or more so, with the master mosaics of the cupola of the Baptistery and with the early Florentine painter, Coppo di Marcolvaldo (1225 – 1276).

|

|

|||

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

||||

Bagni San Filippo |

Arcidosso |

Montalcino, view from the fortress

|

||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, giardino |

Podere Santa Pia |

||