|

Ugolino di Nerio, Madonna col Bambino e Santi (detail), Certaldo, Museo di arte sacra |

Ugolino di Nerio |

Ugolino di Nerio (1280? - 1349) was active in his native city of Siena and in Florence between the years 1317 and 1327. |

| The Santa Croce Altarpiece |

||||

| This series of paintings comes from a group of panels which formed the predella, of the high altarpiece at Santa Croce, Florence. The early Italian High Altar by Ugolino di Nerio for Santa Croce, the great Franciscan church of Florence, is well-documented. With at least thirty-five sections in all, this massive altar was painted and erected c. 1325-30. These panels recall Duccio's sense of style and organization, as Ugolino was still working with Byzantine line and colour. The altar was dismantled shortly after 1566 and moved to the church's dormitory. By the 1830s, most of its panel had been sold. Now the surviving panels are scattered among museums and private collections. The central panel, which depicted the Madonna and Child and was signed by Ugolino, is now lost. |

||||

| The Last Supper |

||||

| This painting of the Last Supper formed part of the predella of the now dismembered altarpiece. |

||||

| The Betrayal of Christ |

||||

| The Roman Soldiers have come to arrest Christ. At the centre Judas betrays Christ with a kiss as described in the New Testament (Matthew 26: 47-52). On the left Saint Peter cuts off the ear of Malchus. The scene takes place at night; illumination is provided by the torches held aloft.

This panel formed the second scene after the 'Last Supper' (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lehman Collection) in the predella of the high altarpiece of S. Croce, Florence. The altarpiece was probably paid for by the Alamanni family, whose coat of arms was originally on it. |

||||

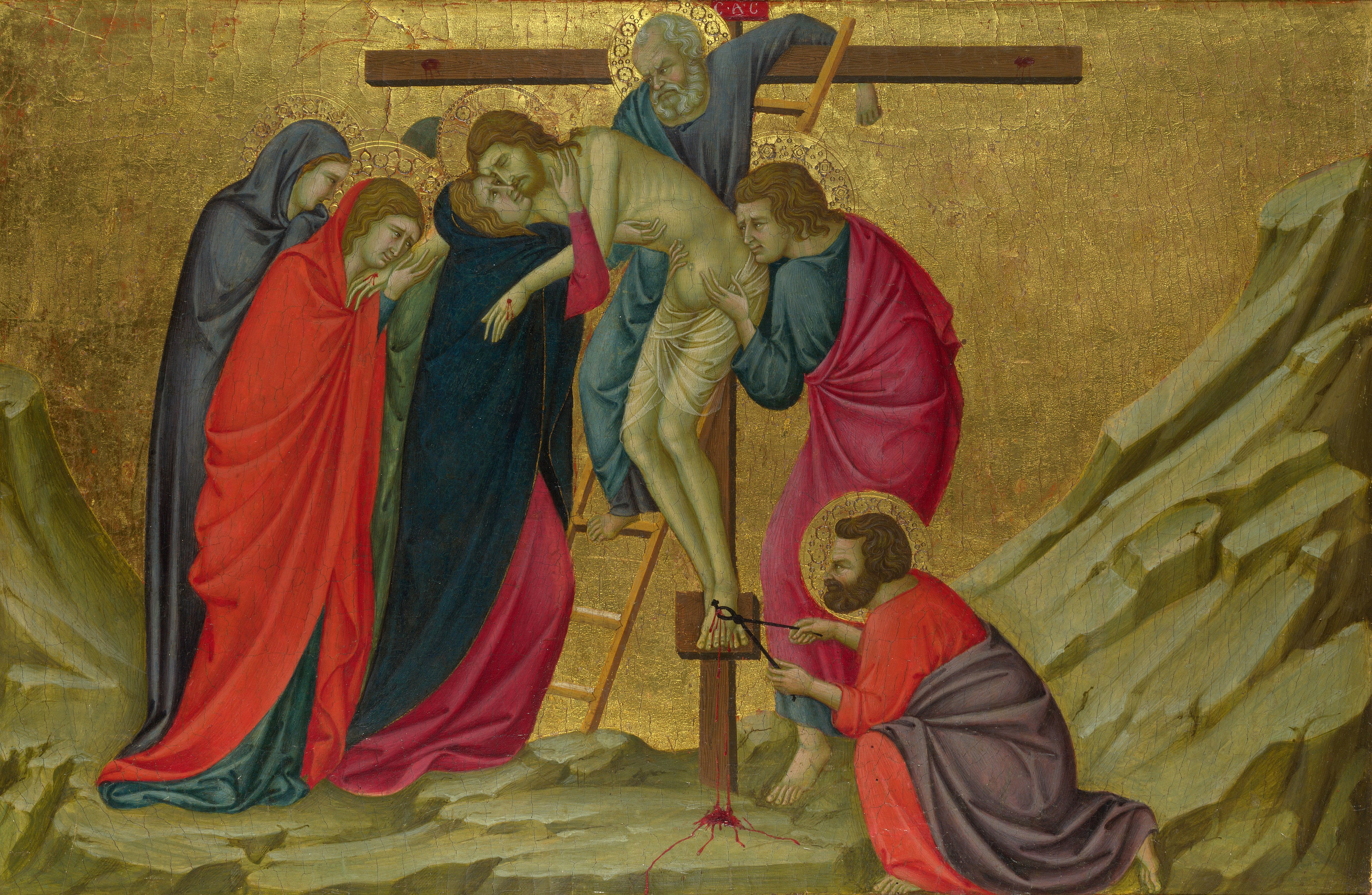

| The Deposition |

||||

| Joseph of Arimathea (?), on the ladder, lowers the dead Christ from the cross. The Virgin, accompanied by the Maries, embraces him. Saint John the Evangelist supports Christ on the right, while Nicodemus (?) removes a nail from his feet. This incident is not described in the Gospels.

This panel formed the fifth of the seven scenes of Christ's Passion in the predella of the high altarpiece of S. Croce, Florence. The composition is similar to that of the same subject in Duccio's Maestà (Siena, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo). |

||||

| Isaiah |

||||

| This three-quarter-length depiction of the Old Testament prophet shows him holding a scroll in his left hand and looking to the left. The inscription derives from his prophecy (Isaiah 7:14), which was interpreted as predicting the birth of Jesus.

This panel formed the second pinnacle from the left of the high altarpiece of S. Croce. |

Der Prophet Jesaja, 1317-1327, National Gallery, London |

|||

|

||||

Ugolino di Nerio, Daniil, 1324, Philadelphia Museum of Art

|

||||

| Saint Simon and Saint Thaddeus (Jude) |

||||

| Saint Simon on the left, holds a book, while Saint Thaddeus, who turns to the right, holds a knife. Three unidentified heads are depicted between decorative motifs in the band of quatrefoils below.

This panel formed the second section from right of the upper tier, below the pinnacles of the high altarpiece of S. Croce, Florence. It was placed beneath the pinnacle depicting Jeremiah and above Saint Francis in the main tier. The tier from which it came showed mainly apostles. |

||||

| Saint Bartholomew and Saint Andrew |

||||

| Saint Bartholomew, at the back, holds a scroll in his left hand and blesses (?) with his right, revealing an ornate garment beneath his cloak. Saint Andrew, at the right, holds a book.

The panel formed the third section from the left, below the pinnacles, of the high altarpiece of S. Croce, Florence. It was above a depiction of Saint Paul in the main tier below 'David'. |

||||

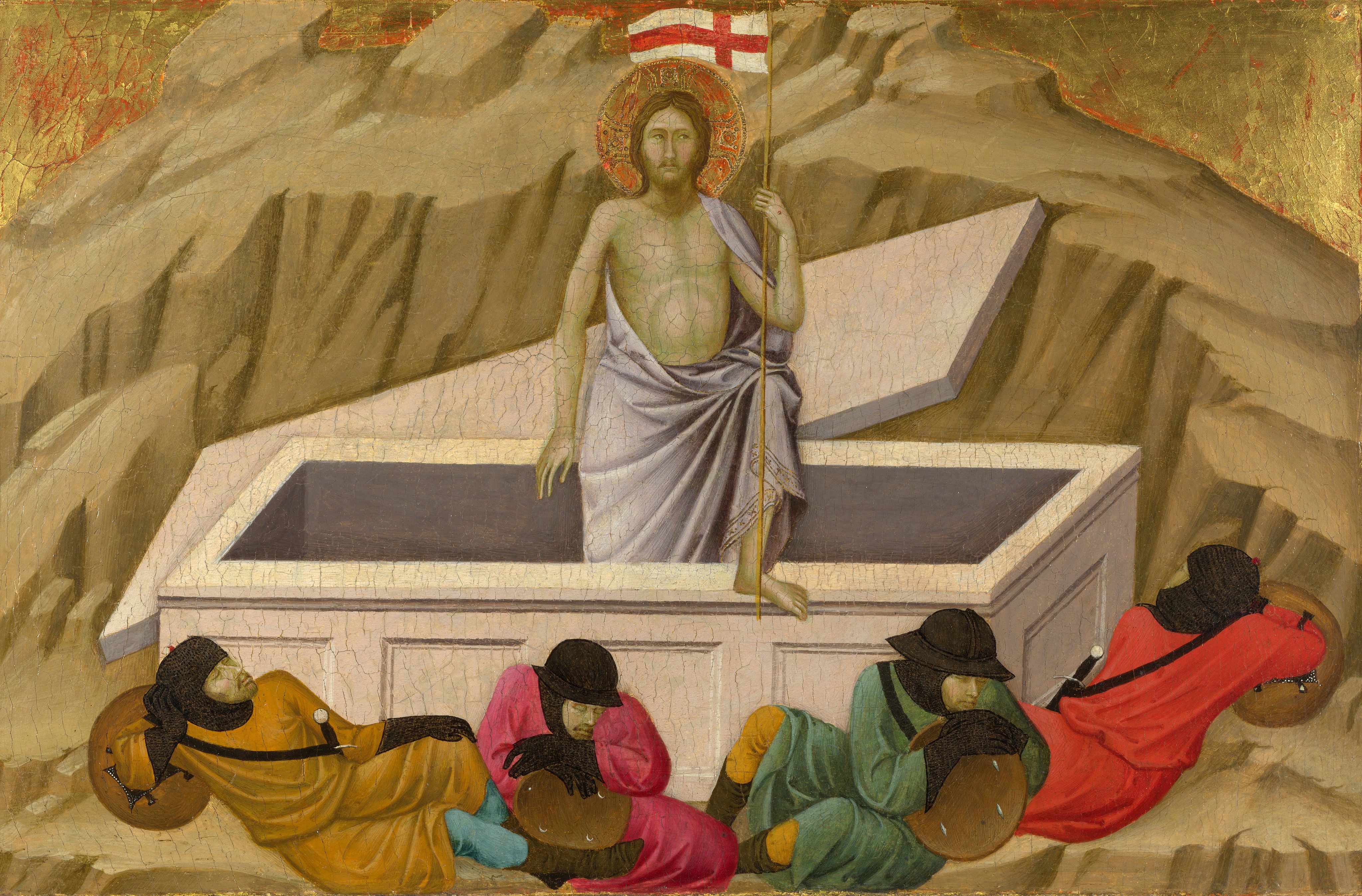

| The Resurrection |

||||

| Christ steps triumphant out of the tomb while four soldiers sleep in the foreground. New Testament (Matthew 28: 2-4). He holds the banner of the Resurrection with a red cross on a white ground. | ||||

| Ugolino di Nerio, Madonna and Child with a Donor, about 1335, San Casciano Val di Pesa, Santa Maria del Prato | ||||

| 'When this damaged but exquisite picture was first published in 1911, it was framed as a triptych with two wings by the Master of Monte Oliveto (41.190.31bc). The triptych must have been a modern creation, for not only are the wings by another master and later in date, but the iconography of the panel, which includes Saints Clare and Francis, is self-sufficient. It was probably painted as an independent devotional panel for a convent of Franciscan nuns, or Poor Clares (the order founded by Clare, the first female follower of Saint Francis). It is a work of extremely high quality. The attribution has been much disputed but the elegantly elongated figures relate in style to the works of Duccio and those of his most faithful follower, Ugolino di Nerio. The picture has, indeed, often been ascribed to a follower or associate of Ugolino. The tooling of the gold is hand-inscribed and this helps to establish a date prior to ca. 1320, when Sienese artists, following the example of Simone Martini, began to use motif punches to decorate the gold background. The picture may be an early work by Ugolino himself.' Catalogue Entry The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York | www.metmuseum.org |

, |

|

||

|

||||

The Santa Croce Altarpiece The predella of the altarpiece painted for the high altar of the Franciscan church of Santa Croce was dismantled in 1566 and installed in the friars' dormitory. At the end of the eighteenth century or in 1810, when the friary was suppressed, most, if not all of the altarpiece entered the Young Ottley Collection. The predella scenes, showing the Passion of Christ, would have had the following pieces: the Last Supper (Lehman Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), the Betrayal (No.1188, National Gallery, London), the Flagellation (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), the ‘Ascent to Calvary’, the Deposition (Nos.1189 and 3375, National Gallery, London), the Entombment (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), and the Resurrection (No.4191, National Gallery, London).

|

||||

| The Last Supper

|

||||

|

||||

Ugolino di Nerio, The Last Supper, 1324-05, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

|

||||

The Betrayal

|

||||

|

||||

Ugolino di Nerio, The Betrayal, 1324-25, painting, National Gallery, London

|

||||

The Flagellation

|

||||

|

||||

Ugolino di Nerio, Flagellation, panel from the Santa Croce Altar, between 1325 and 1330, color on poplar wood, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

|

||||

The Betrayal

|

||||

|

||||

Ugolino di Nerio, The Betrayal, 1324-25, painting, National Gallery, London

|

||||

The Deposition

|

||||

| ||||

| Ugolino di Nerio, The Deposition, 1324-25, painting, National Gallery, London

|

||||

The Entombment

|

||||

|

||||

Ugolino di Nerio, The Entombment, panel from the Santa Croce Altar, between 1325 and 1330, color on poplar wood, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

|

||||

The Resurrection

|

||||

|

||||

Ugolino di Nerio, The Resurrection, 1324-25, painting, National Gallery, London

|

||||

| Painted Cross

|

||||

|

||||

Ugolino di Nerio, Painted Cross, (detail), circa 1330, Santa Maria dei Servi, Siena

|

||||

San Michele Arcangelo

|

||||

|

||||

| Ugolino di Nerio, San Michele Arcangelo, Museo archeologico e d'arte della Maremma

|

||||

San Michele Arcangelo (detail)

|

||||

|

||||

Ugolino di Nerio, San Michele Arcangelo, (detail), Museo archeologico e d'arte della Maremma |

||||

[1] Davies, Martin. In: "National Gallery Catalogues: Catalogue of the Earlier Italian Schools". National Gallery Catalogues, London 1961, reprinted 1986, pp. 108-113. [1] David Bomford; Jill Dunkerton, Dillian Gordon, Ashok Roy, Jo Kirby (10september 1989) (in english) Italian Painting before 1400, London: National Gallery Publications, p. 101 |

||||

|

||||

Wikimedia Commons | Sienese School of painting

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Monte Argentario | |||

Santa Croce, Firenze |

Cipresses between Montalcino and Pienza |

Sovicille |

||

|

||||

Wines in southern Tuscany |

Abbey of Sant 'Antimo | Sunsets in Tuscany |

||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

| Nearby the town of Sant’Angelo in Colle, 6km from Sant’Antimo, an enchanting well-preserved village on the top of a hill contained in its circle of walls. You can walk there on a dirt road from Sant’Antimo or on a paved road from Montalcino. | ||||