|

|

Bernard Berenson in the garden at Villa i Tatti, March 1911 |

|

Bernhard Berenson |

Bernard Berenson (June 26, 1865 – October 6, 1959) was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance. He was a major figure in pioneering art attribution and therefore establishing the market for paintings by the "Old Masters". Berenson died at age 94 in Settignano, Italy. As Renaissance scholarship has evolved, a number of Berenson's attributions are now believed to be incorrect. There is also ongoing speculation as to whether some of these misattributions were deliberate, since Berenson often had a considerable financial stake in the matter. Due to the strong subjective element in connoisseurship, such accusations remain hard to either disprove or substantiate. |

|

| Works * Venetian Painters of the Renaissance (1894) |

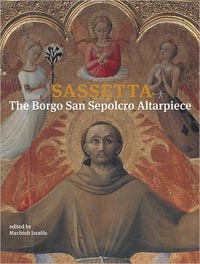

| Besides the villa, his library, and an archive of photographs and other visual images, Mr. Berenson left Harvard his collection of some 120 works of Renaissance and oriental art, which he intended should remain distributed throughout the house. His bequest also included his archive of correspondence and papers, as well as the farmlands and gardens surrounding the Villa. He saw both the collection and the setting as providing encouragement to thoughtful and creative intellectual meditation. According to his own statements (see Bernard Berenson, Abbozzo per un autoritratto, Florence, 1949: 228-229), Berenson collected art works only for the furnishing and decoration of his house, and ceased purchasing toward the middle of the second decade of the twentieth century. At I Tatti Bernard Berenson assmbled a choice collection of Renaissance art, including works by Giotto, Sassetta, Domenico Veneziano, and Lorenzo Lotto. The Madonna and Child in the Berenson Collection is also similarly related to Florentine painting of the 1430s. For this reason it is normally dated at around the same period as the Carnesecchi Tabernacle. The gentle image of the Virgin is placed against a reddish brocade backdrop, creating a very elegant and courtly mood. She offers a flower to the plump little Child. Here, too, the lighting contributes peaceful intimacy to the scene. Gardens in Tuscany | Villa i Tatti in Settignano The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Florentine Painters of the Renaissance, by Bernhard Berenson Dictionary of Art Historians | Bernard Berenson Villa I Tatti | The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies | www.itatti.it Gardens in Tuscany | Cecil Pinsent Art in Tuscany | Domenico Veneziano Russoli, Franco, and Mariano, Nicky. The Berenson Collection. Milan: Arti grafiche Ricordi, 1964 |

||

|

||

[1]Bernhard Berenson and his wife Mary bought Villa I Tatti in 1905. In 1909 they commissioned the English architect Cecil Ross Pinsent (1884–1963) to supervise a series of extensions and alterations to Villa I Tatti, as well as to design a garden and supervise its planting and construction with the help of the English writer-scholar Geoffrey Scott (1884 – 1929). Villa I Tatti, a Medici residence situated between Fiesole and Settignano in the north of Florence has been the headquarters of the Center for Italian Renaissance Studies at Harvard University since 1961. Villa I Tatti | The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies | www.itatti.it

|

||

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia article Bernard Berenson, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. | ||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, giardino |

Podere Santa Pia |

Florence, Duomo |

||

|

||||

Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence |

Certosa del Galluzzo (Firenze) |

Villa I Tatti |

||

|

||||

Villa Arceno gardens |

Abbey of Sant 'Antimo |

Villa La Pietra, near Florence |

||

| Settignano |

||||

| Settignano is a picturesque frazione ranged on a hillside northeast of Florence, Italy, with spectacular views that have attracted American expatriates for generations. The little borgo of Settignano carries a familiar name for having produced three sculptors of the Florentine Renaissance, Desiderio da Settignano and the Gamberini brothers, better known as Bernardo Rossellino and Antonio Rossellino. The young Michelangelo lived with a sculptor and his wife in Settignano—in a farmhouse that is now the "Villa Michelangelo"— where his father owned a marble quarry. In 1511 another sculptor was born there, Bartolomeo Ammanati. The marble quarries of Settignano produced this series of sculptors. Roman remains are to be found in the borgo which claims connections to Septimius Severus—in whose honor a statue was erected in the oldest square in the 16th century, destroyed in 1944— though habitation here long preceded the Roman emperor. Settignano was a secure resort for estivation for members of the Guelf faction of Florence. Giovanni Boccaccio and Niccolò Tommaseo both appreciated its freshness, among the vineyards and olive groves that are the preferred setting for even the most formal Italian gardens. Mark Twain and his wife stayed at the Villa Viviani in Settignano from September 1892 to June 1893, and greatly enjoyed their visit. Twain was very productive there, writing 1,800 pages including a first draft of Pudd'nhead Wilson. He said the villa "afford[ed] the most charming view to be found on this planet." In 1898, Gabriele d'Annunzio purchased the trecento Villa della Capponcina on the outskirts of Settignano, in order to be nearer to his lover Eleanora Duse, at the Villa Porziuncola. Near Settignano are the Villa Gamberaia, a 14th-century villa famous for its 18th-century terraced garden. |

||||

| 1 | A Walk Around the Uffizi Gallery

2 | Quarter Duomo and Signoria Square 3 | Around Piazza della Repubblica 5 | San Niccolo Neighbourhood in Oltrarno 6 | Walking in the Bargello Neighbourhood 7 | From Fiesole to Settignano |

Via Boccaccio leads to the Badia Fiesolana, Fiesole's cathedral until 1028.

|

|||

Fiesole, facade Badia fiesolana

Fiesole, facade Badia fiesolana