|

|

Agnolo Gaddi, The Legend of the True Cross, (detail, the Queen of Sheba), Cappella Maggiore, Basilica di Santa Croce, Firenze |

|

Agnolo Gaddi | The Legend of the True Cross |

| Agnolo Gaddi was a florentine painter and the son of Taddeo Gaddi, one of the foremost pupils of Giotto di Bondone. He continued the Giotto tradition but modified it still further in the direction of decorative elegance. He is particularly notable for his cool pale colours, which influenced the refined late Gothic art of artists of the next generation such as Lorenzo Monaco. Agnolo's works include frescos on The Story of the Cross in the chancel of Sta Croce (after 1374) and on The Story of the Virgin and her Girdle in the Chapel of the Holy Girdle in Prato Cathedral (1392-5). |

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Agnolo Gaddi, La leggenda della Vera Croce, Diagram of the frescoes in the Cappella Maggiore, Basilica di Santa Croce |

||

The inspiration for the mural cycle in the apse derived from the dedication of the church to the True Cross and from the celebration of Santa Croce’s most sacred relic, a splinter of the True Cross, which was housed in a reliquary built by the Venetian goldsmith Bertucci in 1258. The Gaddi paintings are located on the two single bay walls that face each other flanking the altar . Santa Croce possesses a relic of the True Cross, and the church was dedicated to the Holy Cross. The monumental cycle illustrates stories recalled on the two annual feast days celebrating the relic of Christ’s crucifixion. The cycle is composed of eight mostly rectangular panels, each about seven meters wide and four meters high. Each separate register contains one to three scenes from the legend; the episodes are narrated in great detail, with some scenes overlapping. The scenes include: The Death of Adam (Fig. 2), Adoration and Burial of the Wood (Fig. 3), Retrieval of the Wood at the Probatic Pool, and Fabrication of the Cross (Fig. 4), and The Discovery and Testing of the True Cross (Fig. 5). The four scenes on the altar's left (Fig. lb) refer to the events connected to the Exaltation of the Cross. The scenes include St. Helena Returning the Cross to the Jerusalem (Fig. 7), Theft of the Cross (Fig. 8), Chosroes Adored, Dream of Heraclius, Battle of Heraclius and Son of Chosroes (Fig. 9), Execution of Ch osroes, Heraclius Tries to Enter Jerusalem, and Exaltation of the Cross (Fig. 10). The landscape and architectural elements serve only as dividers for the narrative. The decorative beauty of Gaddi's paintings resembles the work of a tapestry. |

||

| The four scenes to the right of the altar (Fig. lc) are connected to the Feast of the Invention of the Cross.

Right wall The Death of Adam Adoration and Burial of the Wood Retrieval of the Wood at the Probatic Pool, and Fabrication of the Cross The Discovery and Testing of the True Cross.

On the left side the four frescoes are connected to the September 14 Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross. The Exaltation scenes include stories that focus on the elevation or praising of the cross. They begin with the left lunette, St. Helena Returning the Cross to Jerusalem. Like the Adam lunette, the scenes are shaped to fit inside the lunette. St. Helena is pictured in a pointed hat holding her attribute, the True Cross, and presenting it to the people of Jerusalem. A group of kneeling dignitaries awaits her at the city gate. The ceremonial conveying of the cross into Jerusalem is rarely depicted. In the background, the landscape recedes into the symbolic city of Jerusalem on the right. St. Helena Returning the Cross to the Jerusalem Theft of the Cross Chosroes Adored, Dream of Heraclius, Battle of Heraclius and Son of Chosroes The panel depicting Chosroes Worshipped by His Subjects, The Dream of Heraclius, and The Defeat of the Son of Chosroes contains three separate parts of the story. To the left Chosroes is exalted by the people in a basilica of gold and silver with the cross; he has chosen to be worshipped as a god. Chosroes holds a scepter, and men kneel before him. In the center, Heraclius has a dream wherein he receives a vision from an angel above the tent holding a wooden cross before battle that signifies his devotion to God; he is pictured reclining in his tent, leaning on his elbow, and gazing up at the vision; above the tent floats the cross and an angel. And on the far right is the climax in which Heraclius administers the final blow to defeat Chosroes' son in single combat on the bridge over the Danube. |

The commissioning of the choir cycle is attributed to the Alberti, a wealthy and influential Florentine banking family who were highly involved in the patronage of art.

Emperor Heraclius lies outstretched on his bed in a tent and looks toward the angel, floating above him, who forecast his victory. The combat Chosroës's son, from which Heraclius emerged victorious, is shown to the right of the tent. |

|

Execution of Chosroes, Heraclius Tries to Enter Jerusalem, and Exaltation of the Cross The final scene contains The Beheading of Chosroes, The Angel Appearing to Heraclius, and the Entry of Heraclius into Jerusalem. The beheading of Chosroes for denouncing the Christian faith takes place on the left-hand side, in front of his palace and a group of men. The tiny bridge in the foreground alludes to the battle at the Danube. In the top center, Heraclius, Emperor of the Byzantines, arrives in splendor on horseback with the rescued relic of the cross at the gates of Jerusalem. An angel appears to Heraclius and reminds him of his need for humility. The city gate is walled up against him. The stones crumble away when Heraclius humbly strips himself of jewels. He is still crowned, but he is barefoot and wears only a simple white shirt. It is only then that he carries the cross upright to the gate and enters Jerusalem to celebrate the Exaltation ofthe cross. The entire story, taken from the Golden Legend, shows the mystical power of the holy wood to persevere throughout the entire span of human history. |

||

|

||

Agnolo Gaddi, The Legend of the True Cross, The Beheading of Chosroes, The Angel Appearing to Heraclius, and the Entry of Heraclius into Jerusalem, Cappella Maggiore, Basilica di Santa Croce, Firenze |

||

| On the two side walls the story of the Saint Cross is depicted, the Triumph of the Cross being the final and most significant scene of the cycle. There are three scenes depicted beside and above each other. On the left side the beheading of Chosroes, King of Persia, for the occupation of Jerusalem and robbing the Cross; behind and above Heraclios arriving to Jerusalem with the regained Cross; on the right side Heraclios bringing the Cross barefooted into Jerusalem. The beheading of Chosroes for denouncing the Christian faith takes place on the leftehand side, in front of his palace and a group of men. The tiny bridge in the foreground alludes to the battle at the Danube. In the top center, Heraclius, Emperor of the Byzantines, arrives in splendor on horseback with the rescued relic of the cross at the gates of Jerusalem. An angel appears to Heraclius and reminds him of his need for humility. The city gate is walled up against him. The stones crumble away when Heraclius humbly strips himself of jewels. He is still crowned, but he is barefoot and wears only a simple white shirt. It is only then that he carries the cross upright to the gate and enters Jerusalem to celebrate the Exaltation ofthe cross. The entire story, taken from the Golden Legend, shows the mystical power of the holy wood to persevere throughout the entire span of human history.[2] There is no difference in the size of the figures, thus no spatial perspective.The majority of the figures are illustrated in profile. Traditionally it is believed that the man standing beside the executioner is the painter himself. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Agnolo Gaddi, The Legend of the True Cross, the Entry of Heraclius into Jerusalem (detail) |

||

Scenes from the Exaltation of the Cross

|

||

| On the left side the four frescoes are connected to the September 14 Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross. The Exaltation scenes include stories that focus on the elevation or praising of the cross. They begin with the left lunette, St. Helena Returning the Cross to Jerusalem. Like the Adam lunette, the scenes are shaped to fit inside the lunette. St. Helena is pictured in a pointed hat holding her attribute, the True Cross, and presenting it to the people of Jerusalem. A group of kneeling dignitaries awaits her at the city gate. The ceremonial conveying of the cross into Jerusalem is rarely depicted. In the background, the landscape recedes into the symbolic city of Jerusalem on the right. [2] |

||

Chosroes Worshipped by His Subjects, The Dream of Heraclius, and The Defeat of the Son of Chosroes |

||

The panel depicting Chosroes Worshipped by His Subjects, The Dream of Heraclius, and The Defeat of the Son of Chosroes contains three separate parts of the story. To the left Chosroes is exalted by the people in a basilica of gold and silver with the cross; he has chosen to be worshipped as a god. Chosroes holds a scepter, and men kneel before him. In the center, Heraclius has a dream wherein he receives a vision from an angel above the tent holding a wooden cross before battle that signifies his devotion to God; he is pictured reclining in his tent, leaning on his elbow, and gazing up at the vision; above the tent floats the cross and an angel. And on the far right is the climax in which Heraclius administers the final blow to defeat Chosroes’ son in single combat on the bridge over the Danube.[2] |

||

|

||

Agnolo Gaddi, The Legend of the True Cross, Chosroes Worshipped by His Subjects, The Dream of Heraclius, and The Defeat of the Son of Chosroes |

||

|

||

Retrieval of the Wood at the Probatic Pool, and Fabrication of the Cross |

||

|

||

Agnolo Gaddi, The Legend of the True Cross, Agnolo Gaddi, La Leggenda della Vera Croce, Retrieval of the Wood at the Probatic Pool, and Fabrication of the Cross |

||

|

||

The Discovery and Testing of the True Cross |

||

|

||

Agnolo Gaddi, La Leggenda della Vera Croce, The Discovery and Testing of the True Cross |

||

|

||

|

||

Detail from The Discovery and Testing of the True Cross, after the restauration |

||

The background scene of The Discovery and Testing of the True Cross appears to depart from the legend established in at the end of the fourth century and beginning of the fifth century of St. Helena's discovery of the True Cross.v It is a scene from the Life of St. Francis. Francis can be seen in the background landscape and town scene. It is the background scene that is of greatest importance to the Franciscan connection discussed in Chapter Three. There is a river and a well. Two monks can be seen performing simple, everyday tasks: one appears to be fishing and another draws water from the well. Looming above, a lion rests in a cave. |

||

|

||

| [1] For a recent biographical entry see C. Frosinini, Agnolo Gaddi, in La Sacra Cintola nel Duomo di Prato, Prato 1995, pp. 225-233 [2] Tracey Hirstius Barhorst, Agnolo Gaddi: Issues of Patronage and Narrative in the Selection of the True Cross Cycle at Santa Croce, Florence, B. A., Louisiana State University, 1993 | www.etd.lsu.edu Abstract | Agnolo Gaddi’s Legend of the True Cross fresco cycle in the sanctuary of Santa Croce, Florence, represents an unusual artistic program. Initiated by the Franciscans around 1388, Gaddi’s is the earliest monumental True Cross program; it set the standard for similar works into the sixteenth century. |

|

|||

Santacroceopera.it - Museo dell'Opera | www.santacroceopera.it To find out more about the restoration of this work, or to zoom in and study the frescoes if you can’t go in person, you can use the Modus Operandi online interactive documentation system. Get to know Gaddi up close at Santa Croce | www.arttrav.com Art in Tuscany | Italian Renaissance painting Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects Volume I | Cimabue to Agnolo Gaddi |

||||

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia articles Agnolo Gaddi, Leggenda della Vera Croce published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Val d'Orcia |

|||

|

||||

Villa Celsa near Florence |

Corridoio Vasariano, Firenze |

Massa Marittima |

||

Montefalco |

Bagni San Filippo |

Florence, Duomo |

||

|

||||

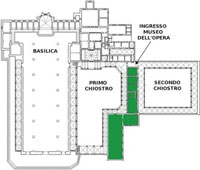

Santa Croce | The Museo dell’Opera |

||||

| The Basilica is the largest Franciscan church in the world. Its most notable features are its sixteen chapels, many of them decorated with frescoes by Giotto and his pupils, and its tombs and cenotaphs. Legend says that Santa Croce was founded by St Francis himself. The construction of the current church, to replace an older building, was begun on 12 May 1294,possibly by Arnolfo di Cambio, and paid for by some of the city's wealthiest families. The Basilica of Santa Croce is also known as the Temple of the Italian Glories, as many important artists, writers and scientists, including Michelangelo Buonarroti, Galileo Galilei, Gioachino Rossini, Ugo Foscolo and Leon Battista Alberti are buried here. In 1966, the Arno River flooded much of Florence, including Santa Croce. The water entered the church bringing mud, pollution and heating oil. The damage to buildings and art treasures was severe, taking several decades to repair. The Museo dell'Opera di Santa Croce is housed mainly in the refectory, also off the cloister. The Museum was founded on the 2nd of November 1900 by Guido Carocci, who converted the Refectory, the Cenacolo, previously used as a storeroom for paintings and objets d’art, into a public exhibition hall. The Museo dell’Opera

|

||||