| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

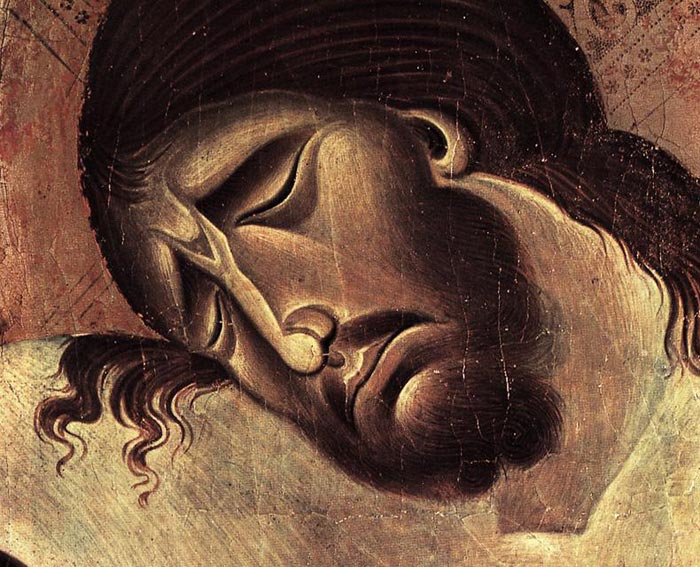

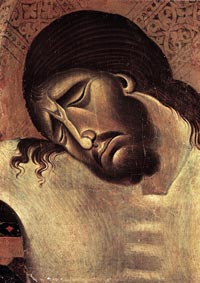

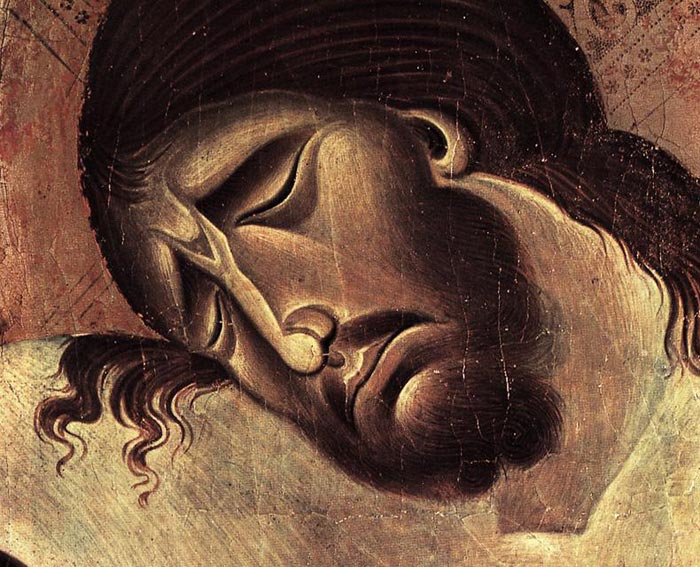

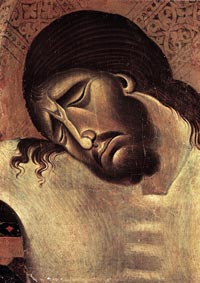

Cimabue, Crucifix (detail), 1268-71, tempera on wood, 336 x 267 cm, San Domenico, Arezzo

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Cenni di Pepe, known as Cimabue (c. 1240 – c. 1302)

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Cenni di Pepo (Giovanni) Cimabue (c. 1240 – c. 1302), also known as Bencivieni di Pepo or in modern Italian, Benvenuto di Giuseppe, was an Italian painter and creator of mosaics from Florence.

His nickname means either bull-head or possibly ‘one who crushes the views of others’ (It. cimare: ‘top, shear, blunt’), an interpretation matching the tradition in commentaries on Dante that he was not merely proud of his work but contemptuous of criticism.

Cimabue may be considered the most dramatic of those artists influenced by contemporary Byzantine painting through which antique qualities were introduced into Italian work in the late 13th century. His interest in Classical Roman drapery techniques and in the spatial and dramatic achievements of such contemporary sculptors as Nicola Pisano, however, distinguishes him from other leading members of this movement. As a result of his influence on such younger artists as Duccio and Giotto, the forceful qualities of his work and its openness to a wide range of sources, Cimabue appears to have had a direct personal influence on the subsequent course of Florentine, Tuscan and possibly Roman painting.

As the most celebrated Florentine artist of his generation, Cimabue won acclaim for his achievements in naturalistic representation and emotional expression in monumental altarpieces, frescoes, and mosaics. Cimabue's only documented work is the apse mosaic of 'Saint John the Evangelist' in the Duomo (cathedral) in Pisa of 1301 and 1302. His surviving works include the large Crucifix for Sta. Croce in Florence — about 70 percent destroyed in the floods of 1966, though restoration has been completed — the Sta. Trinità Madonna, an altarpiece now in Florence’s Uffizi, and the Madonna Enthroned with St. Francis, in the lower church of S. Francesco at Assisi.

Cimabue is generally regarded as the last great Italian painter working in the Byzantine tradition.[1] The art of this period comprised scenes and forms that appeared relatively flat and highly stylized. Cimabue was a pioneer in the move towards naturalism, as his figures were depicted with rather more life-like proportions and shading. Even though he was a pioneer in that move, his painting Maesta shows Medieval techniques and characteristics. The painting is commonly regarded as a painting which exemplified the Middle Ages. He is also well known for his student Giotto, considered the first great artist of the Italian Renaissance.

Owing to little surviving documentation, not much is known about Cimabue's life. He was born in Florence and died in Pisa. His career was described in Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (called, in Italian, Le Vite), widely regarded as the first art history book, though it was completed over 200 years after Cimabue's death. Although it is one of the few early records we have of him, its accuracy is uncertain. According to Hugh Honour and John Fleming: "His name is, in fact, little more than a convenient label for a closely related group of panel and wall paintings".[2]

Cimabue led the artistic movement in late 12th-century Tuscany that sought to renew the pictorial vocabulary and break with the rigidity of Byzantine art. The artist demonstrated a new sensibility, which endeavored to adhere more closely to reality.

His only secure work is a mosaic of Saint John in Pisa Cathedral, dated 1301-2. On the basis of this mosaic a number of paintings are attributed to him, including the Santa Trinita Madonna (about 1280, Uffizi, Florence) and the now ruined Crucifix in S. Croce, Florence. A now lost altarpiece, dated 1301, may have been the earliest to have a predella.

Judging this by the commissions that he received, Cimabue appears to have been a highly-regarded artist in his day. He was influenced by Dietisalvi di Speme. While he was at work in Florence, Duccio was the major artist, and perhaps his rival, in nearby Siena. Cimabue was commissioned to paint two very large frescoes for the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi. They are on the walls of the transepts: a Crucifixion and a Deposition. Unfortunately these works are now dim shadows of their original appearance. During occupancy of the building by invading French troops, straw caught fire, severely damaging the frescoes. The white paint was partially composed of silver, which oxidised and turned black, leaving the faces and much of the drapery of the figures in negative.

Another damaged work is the great Crucifix of Santa Croce at Florence. It was the major work of art lost in the flood in Florence in 1966. Much of the paint from the body and face washed away.

Among Cimabue's few surviving works are the Madonna of Santa Trinita, once in the church of Santa Trinita, and now housed, with Duccio's Rucellai Madonna and Giotto's Ognissanti Madonna, in the Uffizi Gallery.

In the Lower Church of Saint Francis in Assisi is an extremely important fresco, depicting The Madonna and Christ Child enthroned with angels and Saint Francis. It is claimed to be a work of Cimabue's old age.

Two additional, very fine paintings are attributed to Cimabue. The Flagellation of Christ was purchased by New York's Frick Collection in 1950 and was long considered to be of uncertain authorship, possibly Duccio's. But in 2000, the National Gallery in London acquired The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Two Angels with many similarities (size, materials, red borders, incised margins, etc.) to Flagellation. The two pictures are now thought to be parts of a single work, a diptych or triptych altarpiece, and their attribution to Cimabue is fairly secure. The pair are believed to date from 1280. The Virgin and Child was on loan to the Frick for a few months in late 2006, so the two works could be viewed side-by-side. The Flagellation painting is one of only two Cimabues permanently in the United States.

A tiny devotional painting of a "Madonna and Child with SS. Peter and John the Baptist" at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC was painted by Cimabue or one of his students around 1290. It is significant because it shows a cloth of honor that may well be the first patchwork quilt in Western art.

Legacy

History has long regarded Cimabue as the last of an era that was overshadowed by the Italian Renaissance. In Canto XI of his Purgatorio, Dante laments Cimabue's quick loss of public interest in the face of Giotto's revolution in art:[3]

O vanity of human powers,

how briefly lasts the crowning green of glory,

unless an age of darkness follows!

In painting Cimabue thought he held the field

but now it's Giotto has the cry,

so that the other's fame is dimmed.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

The Madonna and Child in Majesty Surrounded by Angels

|

|

Cenni di Pepe, known as Cimabue, The Madonna and Child in Majesty Surrounded by Angels (detail), c. 1280, Musée du Louvre, Pari

s

|

| The frame is decorated with twenty-six painted medallions depicting Christ and four angels, as well prophets and saints. This is one of Cimabue's early works, painted in about 1280, well before the Maestà di Santa Trinità (Florency, Uffizi). A lack of consensus in attributing this painting to the Florentine master is due in large part to the later date of execution traditionally assigned to it, difficult to reconcile with the hieratic and dramatic style.

The iconography of the Maestà - the Child and the Virgin, glorified as queen of heaven, and surrounded by a host of angels - is accentuated by the monumentality of the retable and the sumptuous gold ground. On the original frame, twenty-six painted medallions depict Christ and four angels, as well as saints and prophets.

This work was described by Vasari in 1568 as being found in the church of San Francesco in Pisa, whose high alter it adorned. For this reason, certain specialists have linked this work with Cimabue's stay in Pisa from 1301 to 1302. However, stylistic analysis of the painting and comparisons made between it and the Maestà painted at a later date for the Santa Trinità church in Florence (Florence, Uffizi) suggest an earlier date of execution - around 1280. Nevertheless, the work already contains elements that attest to the investigations and aspirations of the artist responsible for the rebirth of painting in Italy.

The composition of the Maestà is symmetrical and dense. The imposing Virgin is hieratic, and the blessing gesture of the Christ Child is hardly child-like; however, Cimabue gently and subtly models the faces, endowing the figures with a new sense of humanity. The drapery, not simply drawn either, seems to fold naturally, following the movement of the bodies (for example, the cloaks of the two angels in the foreground whose knees protrude). This demonstrates the undoubted influence of sculptors such as Nicola Pisano.

Cimabue's palette is delicate, with shaded tones, notably in the angels' wings. The figures take on real solidity and an unprecedented visual presence. The artist prepared the ground for 14th-century Florentine art. His works raise the issues that would preoccupy his successors, notably Giotto: the representation of space, the representation of the body, and light.

|

|

Cimabue, The Madonna and Child in Majesty Surrounded by Angels, c. 1280, Musée du Louvre, Paris Cimabue, The Madonna and Child in Majesty Surrounded by Angels, c. 1280, Musée du Louvre, Paris

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maestà del Louvre, dettaglio del volto della Vergine |

|

Maestà del Louvre, dettaglio del Bambino

|

|

Maestà del Louvre, dettaglio dell'Angelo e del trono |

| |

|

|

|

|

Maestà of Santa Trinita

|

|

Cimabue, Maestà (Santa Trinita Madonna), 1280-1285, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

|

Among Cimabue's few surviving works are the Madonna of Santa Trinita, once in the church of Santa Trinita, and now housed, with Duccio's Rucellai Madonna and Giotto's Ognissanti Madonna, in the Uffizi Gallery.[3]

Cimabue painted this stylized and beautiful Madonna on wood panel for the high altar of the church of Santa Trinita ("Holy Trinity") in Florence, Italy. Santa Trinita is the main church of the Vallumbrosan Order of monks founded in 1092. The church has about 20 chapels that contain a great number of master frescoes and paintings.

The Santa Trinita Madonna, Cimabue's major surviving example of altarpiece art, is — like the Rucellai Madonna, by Duccio di Buoninsegna (c.1260-1319) — one of the most majestic of the series of huge gabled panel-paintings of the Madonna and Child which culminates in Ognissanti Madonna (1307) by Giotto. It employs convincing linear perspective with a tentative central vanishing point, and marks a significant step in the Florentine depiction of realistic pictorial space. |

|

Santa Trinita Madonna, Painted around 1280 for the high altar of the church of Santa Trinità. At the Uffizi since 1919 |

| |

|

|

The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Two Angels |

| |

The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Two Angels is the only work by Cimabue in Great Britain and one of only two surviving small-scale paintings by the artist. It almost certainly formed part of a diptych, probably showing several scenes from the Passion of Christ, which included the Flagellation in the Frick Collection, New York. The other scenes, probably six, are lost.

The large Madonna Enthroned from the Church of Sta Trinita in Florence (1280-1285) is one of the best paintings to study in order to understand Cimabue's art. The artist retained a number of Byzantine motifs but forsook the austere, hieratic remoteness of the typical Byzantine Virgin for a softer, more human warmth. She is more accessible, more loving, more the earthly mother. Cimabue, furthermore, showed a concern for the realistic depiction of space in his arrangement of the angels around the throne and in the perspective of the throne itself. The four busts which appear in openings below the throne are without precedent. They give the panel an architectural stability and importance not found in any other work of the period.

The painting is a small-scale representation of the monumental versions of the Maestà which Cimabue painted on panel for Santa Trinita, Florence and S. Francesco, Pisa. Although Italian artists were still influenced by the formal style of Byzantine painting, Cimabue's composition attempts to indicate three-dimensional space by placing the wooden throne at an angle. The Christ Child clings to his mother's hand like a small baby, instead of raising his hand in the gesture of blessing usually seen in Byzantine art.

In his Virgin and Child Enthroned with Two Angels, Cimabue painted the Blessed Mother with Christ Child in hand, flanked by two angels while seated majestically in an oversized wooden throne. The four figures (who do not interact with one another) form a static and iconic devotional work. Along with the panel owned by The Frick Collection (above), recent scientific studies have revealed that the National Gallery's painting was also part of the same lost altarpiece painted by Cimabue. |

|

|

| |

|

|

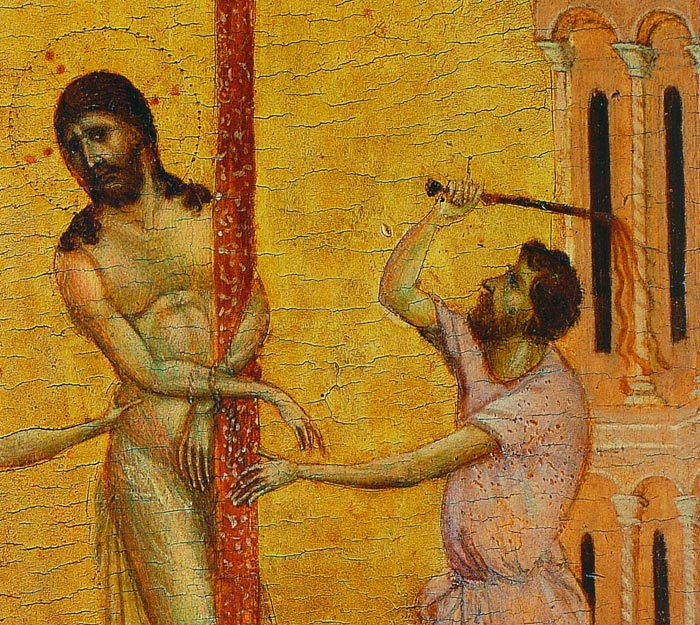

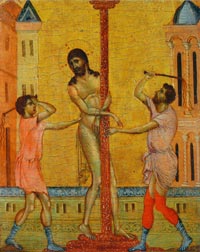

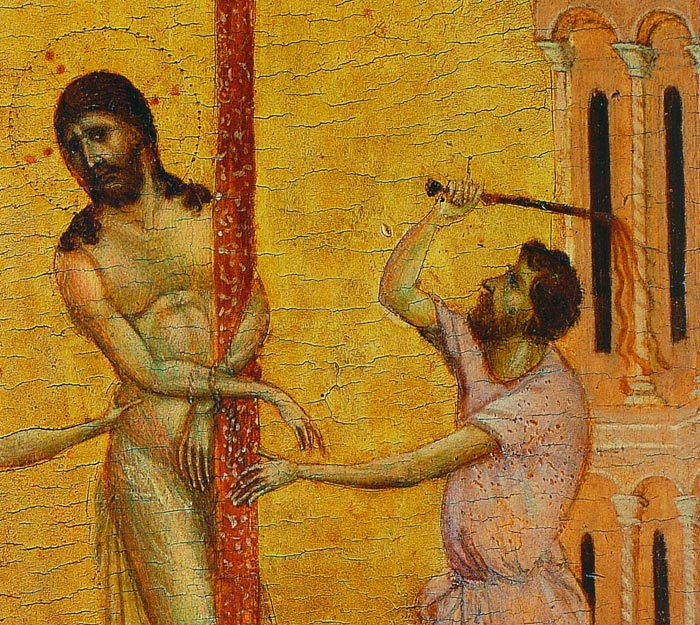

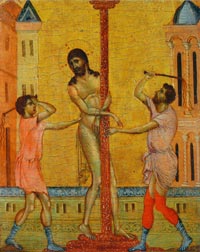

The Flagellation of Christ

|

|

Cimabue, The Flagellation of Christ (detail), Frick Collection, New York City

|

Together with the younger Duccio and Giotto, Cimabue was one of the pioneering artists of the early Italian Renaissance.

His works represent a crucial moment in the history of art when Italian painters, while still influenced by Byzantine painting, were exploring the naturalistic depiction of forms and three-dimensional space.

Cimabue's only documented work is the apse mosaic of 'Saint John the Evangelist' in the Duomo (cathedral) in Pisa of 1301 and 1302. His surviving works include the Santa Trinita 'Maestà' (about 1280, Uffizi, Florence), frescoes in the Lower Church of S. Francesco, Assisi and the now ruined 'Crucifix' in Santa Croce, Florence.

In 1950 The Frick Collection acquired an extremely rare small-scale painting attributed to Cimabue, The Flagellation of Christ. Scholars immediately recognized the work’s beauty and importance but debated whether it was in fact a work by Cimabue or by his Sienese counterpart, Duccio di Buoninsegna (c. 1255–1319). Cimabue's Flagellation is set against a gold background, reflecting the painter's Byzantine artistic heritage. The hands of Jesus Christ are bound to a thin column that vertically divides the panel's cityscape. Cimabue had not yet fully mastered the concept of perspective, hence his rudimentary rendering of the architecture and space in the panel's composition.

In 2000 another small painting by Cimabue, The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Two Angels, was discovered in a private collection in Britain. Scholars attributed this previously unknown work to Cimabue based on stylistic comparisons to one of his celebrated altarpieces, the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Angels (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Studies further revealed that The Virgin and Child Enthroned, now in the collection of the National Gallery, London, and the Frick Flagellation once formed part of the same larger work, possibly a small altarpiece, or a diptych or triptych used for prayer. At an unknown date, this work was cut apart, and its individual scenes entered the art market as independent panels.[3] |

|

Cimabue, The Flagellation of Christ, Frick Collection, New York City |

| |

|

|

|

|

Crucifix, 1268-71, 336 x 267 cm, San Domenico, Arezzo |

| Two painted wood crucifixes demonstrate the evolution of Cimabue's style. In the earlier work, in San Domenico, Arezzo, the artist retained traditional Italo-Byzantine conventions, especially in the linear definition of muscles, treatment of the hair, gold striations in the opaque loincloth, and two bust-length portraits in the terminals. The later work, formerly in Santa Croce, Florence, which probably dates from about the same time as the murals in Assisi, showed a new softness of modeling and abandonment of some Byzantine conventions, like gold striations. The torso of Christ was modeled with broad, widely varied tones which tended to suppress the tortoiseshell appearance seen in the Arezzo crucifix. In the Florence crucifix Cimabue was moving further along the path toward greater naturalism. |

|

Crucifix, 1268-71, San Domenico, Arezzo |

| |

|

|

Among the major works attributed to Cimabue is the large cross in the church of Saint Domenico in Arezzo. It is believed that the painting dates to around 1270. An innovative element is that is depicts Christ in the dramatic moment of his death, underlining the commonality with human suffering. This painting, while innovative in many respects, is not yet the full expression of Cimabue's later style.

The Santa Croce Crucifix in Firenze is probably one of the most recognized of Florence's treasures. Badly damaged by the Arno flood of 1966, it now hangs in the refectory of the Museo dell'Opera di Santa Croce.

Vasari and others cited this crucifixion as an example for Cimabue's innovation: for breaking away from the Byzantine style and achieving a powerful new connection to Christ's humanity and emotion. Time damaged the piece badly, and a flood invaded Santa Croce in 1966 and removed much of the paint.

1966 is the year of the Great Arno Flood. In early November, waters galloped down from the inundated Casentino and rose rapidly to a depth of 20 feet, drowning people as far from the riverbank as the Santa Maria Novella underpass. Thousands of tons of mud destroyed or damaged art on a massive scale, including Cimabue's "Crucifix." Although it survived, and is back on show after painstaking restoration, about 60 percent of its paint has been lost forever.

Art in Tuscany | Cimabue, the Crucifix of Santa Croce at Florence |

|

Cimabue, Crucifix (detail), 1268-71, tempera on wood, 336 x 267 cm, San Domenico, Arezzo

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Giorgio Vasari, Cimabue, portrait medallion in the upper frieze in the Sala Grande, north-east wall, Casa Vasari, Florence

|

Art in Tuscany | Byzantine art

Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects, Cimabue

[1] Byzantine art is the term commonly used to describe the artistic products of the Byzantine Empire from about the 4th century until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. Just as the Byzantine empire represented the political continuation of the Roman Empire, Byzantine art developed out of the art of the Roman empire, which was itself profoundly influenced by ancient Greek art. Byzantine art never lost sight of this classical heritage. The art produced during the Byzantine empire, although marked by periodic revivals of a classical aesthetic, was above all marked by the development of a new aesthetic.

The most salient feature of this new aesthetic was its “abstract,” or anti-naturalistic character. If classical art was marked by the attempt to create representations that mimicked reality as closely as possible, Byzantine art seems to have abandoned this attempt in favor of a more symbolic approach.

[2]

[3] At first glance, the two Cimabue panels appear different, owing to the presence of a modern-day varnish on the National Gallery panel. Their carpentry, condition, style, and technique, however, attest to their origins as part of the same work, either a small altarpiece, diptych, or triptych. The grain of the wood, the thickness of the panels (both of which have been thinned down since they were first painted), the pattern of craquelure in the paint, and even the worm holes in the wood are comparable. Both feature a similar border in the gold ground, consisting of two rows of pinprick-like punches surrounding a delicate scroll pattern formed by tiny punch marks. Such parallels between the Virgin and Child and the Flagellation confirm that both were once part of the same work. At an unknown date, the larger ensemble was cut apart, probably so that smaller pieces of it could be sold as individual works, a fate that befell many early Italian pictures during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. On the Flagellation, the painted surface stops short of the edge of the panel and curls upward with raised edges (barbes) at the bottom and right sides, indicating that it once was framed on those two sides and therefore must have been positioned at the lower-right corner of a larger painted panel. Similarly, the left side and top of the Virgin and Child is barbed, indicating that it formed the upper-left corner of the same work.

Cimabue and Early Italian Devotional Painting | Frick Collection, New York City

[3] Purgatio XI, cited in the Cenni di Petro Cimabue article in the Catholic Encyclopedia. Dante, who refers to Cimabue as an artist who was 'believed to hold the field in painting' only to be eclipsed by Giotto's fame. Ironically enough this passage, meant to illustrate the vanity of short-lived earthly glory, has become the basis for Cimabue's fame; for, embroidering on this reference, later writers made him into the discoverer and teacher of Giotto and regarded him as the first in the long line of great Italian painters.

|

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

| |

|

|

. |

|

|

Podere Santa Pia

|

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, December

|

|

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montecristo

|

|

|

|

|

|

Early morning light at the swimming pool at Podere Santa Pia, with the elegant EMU garden furniture

|

|

In the resplendent Tuscan sun, time

takes on a languid quality

|

|

Evenings around the pool in Tuscany offer a totally different quality of light and amazing colors

|

|

|

|

|

|

Century-old olive trees, between Podere Santa Pia and Cinigiano

|

|

Siena, Duomo |

|

|

Siena universally known for its artistic patrimony and for the substantial stylistic unity of its medieval urban architecture. It has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Siena was founded as a Roman colony in the time of Emperor Augustus, and took the name of Saena Julia. The scarse yet reliable evidence of a preceeding period suggests the existence of an Etruscan community on which the Roman military colony settled during the time of Augustus. In the 10th century, Siena found itself at the centre of important commercial roadways that lead to Rome and, thanks to this, became and important medieval city. In the 12th century the city formed comunal consular ordinances, and began to expand its territory and form its first alliances. This political and economic situation led Siena to battle with Florence over the dominion of northern provinces of Tuscany. From the first half of the 12th century, Siena prospered and became an important commercial centre, holding a good relationship with the Church State; the Sienese bankers were a point of reference the authorities in Rome, to whom they gave loans or financing. At the end of the 12th century Siena supported the Ghibelline cause and found herself again against Florence, which at first suffered the worst, but then the Sienese lost the war at the battle of Colle Val d’Elsa, that brought in 1287 the government of the Nove (Nine). Under this new government, Siena reached her greatest splendor, both economic and cultural. After the Black Death of 1348 , the Sienese Republic began its slow decline, that reached its epilogue in 1555, the year in which the city had to surrender to the Florentine surpremacy.

Cortona is an attractive place to spend a day or two with great art, great atmosphere, stupendous views to Lake Trasimeno and the Val di Chiana. Cortona also boasts one of the earliest convents founded by Saint Francis (1211), hidden in an enchanting gorge nearby. It also has some beautiful churches, such as "Madonna del Calcinaio", designed and built by Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1485) and a distinguished art gallery, il Museo Diocesano, housing works by Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca and his pupil Luca Signorelli, a native of Cortona.

Cortona was s a well-known Umbrian hill town before Frances Mayes wrote about renovating her house, “Casa Bramasole”, near here. The Cathedral is one of the oldest, if not the oldest church in town. The church was built in the 4th century at the dawn of the Christian age on the site of a pre-existing pagan temple. The church stands on the remains of the Etruscan and medieval walls running from the Porta Santa Maria gate to the Porta Colonia gate. Around the year 1000 the romanesque parish church of Santa Maria was built on the site of the previous church; the parish church was later remodelled by Nicola Pisano in 1262. The construction of the current church was started on June 9 1481; construction ended in 1507 and the church was consecrated a cathedral on June 9 1508.

The attribution of the original design to Giuliano da Sangallo and the school of Brunelleschi is still, in the absence of relevent documents, under debate.

The Santa Maria Nuova church stands lofty in a small dell located to the north-west of the town on the side of the road that once connected the Porta Colonia gate with the Franciscan Convent of Le Celle. Its construction was started in 1550 in an area where Etruscan remains were found to designs by architect Sensi, known as Cristofanello and went on in the following years under the direction of Giorgio Vasari that introduced substantial changes to the original project. Except for the dome the costruction ended in 1586; the church was consecrated a collegiate church in 1610 by bishop Bardi. In 1786 arch-duke Pietro Leopoldo suppressed the collegiate church that had in the meanwhile received the “distinguished” title and was demoted to priory.

San Niccolò

The San Niccolò church was built in the 15th century and features an elegant portico on the façade and on the left hand side. The church has a 15th century exterior appearance and is topped by an elegant triple bell bell-gable; the interior features three altars and on the side walls you will be able to see some 18th century wooden benches used by the members of the local Compagnia; the episcopal coat of arms of San Niccolò is painted on all benches. The church houses outstanding works of art amongst which a masterpiece by Luca Signorelli standing above the main altar and portraying the deposition of Christ from the Cross. A small chapel probably built to house the wooden statue of Christ walking to the Calvary opens on the right hand side of the entrance.

Orvieto's Duomo is one of the top three cathedrals in Central Italy. Orvieto Cathedral houses the Capella della Madonna di San Brizio, the San Brizio Chapel, famous for the fresco cycle by Luca Signorelli (painted 1499 - 1503) depicting visions of paradise, hell and the end of the world.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|