|

| Antonio and Piero del Pollaiuolo, Altarpiece of the Saints Vincent, James and Eustace, 1468, tempera on panel, 172 x 179 cm, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi |

Antonio del Pollaiuolo |

| Antonio del Pollaiolo (January 17, 1429/1433 – February 4, 1498), also known as Antonio di Jacopo Pollaiuolo or Antonio Pollaiolo, was an Italian painter, sculptor, engraver and goldsmith during the Renaissance. |

Angel, fresco in San Miniato al Monte

|

||

|

||

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Angel (detail), 1467, fresco, San Miniato al Monte, Florenc |

||

| This angel is on the altar wall of the Chapel of the Cardinal of Portugal in the San Miniato al Monte, Florence. | ||

|

||

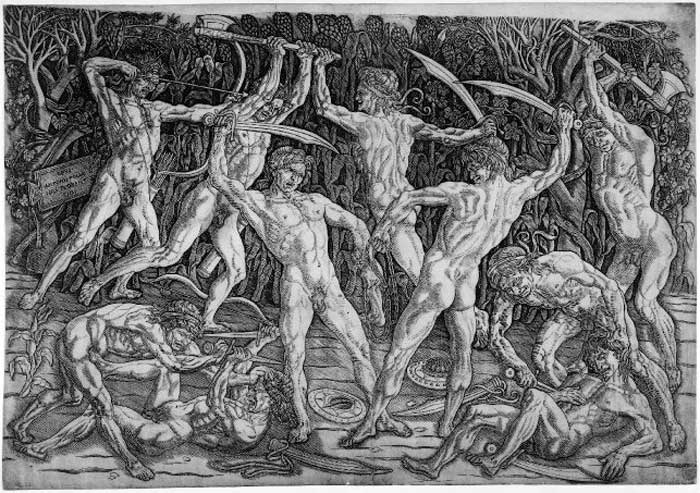

Today, however, a relatively small number of his works survive, and he is perhaps best known for his magnificent engraving, Battle of the Nudes. The Battle of the Nudes is reproduced in nearly all major art history and Renaissance art survey texts. The print is one of the earliest works of Renaissance art to convincingly portray the figure in motion and to suggest how muscles behave under the stress and strain of violent or vigorous activity. |

||

Battle of the Nudes |

||

|

||

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Battle of the Nudes, 1465–1475. Engraving 42.4 x 60.9 cm. Second-state impression at the British Museum

|

||

Perhaps the single best-known work by Pollaiuolo is the engraving Battle of the Nudes. Its status as a monument of fifteenth-century Italian art, however, has not provided certainty about any of its various aspects. The print depicts ten men, silhouetted with little overlapping, on a shallow stage created by a dense background of plants, including a kind of corn, and a vine bearing grapes. Most of the ten men can be roughly paired, as mirror images of each other, a feature relatively common in works by Pollaiuolo, as in the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. |

||

The engraving was widely circulated and is often credited with the dissemination of Italian Renaissance ideals - particularly the modeling of the human form. German artists such as Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) and Jorg Breu (c. 1480-1573) are known to have used the engraving as a model for their own compositions. Its impact on other artists work is evident in their references to the dynamic poses, anatomical explicitness and expressive character of Pollaiuolo's figures. |

||

|

||

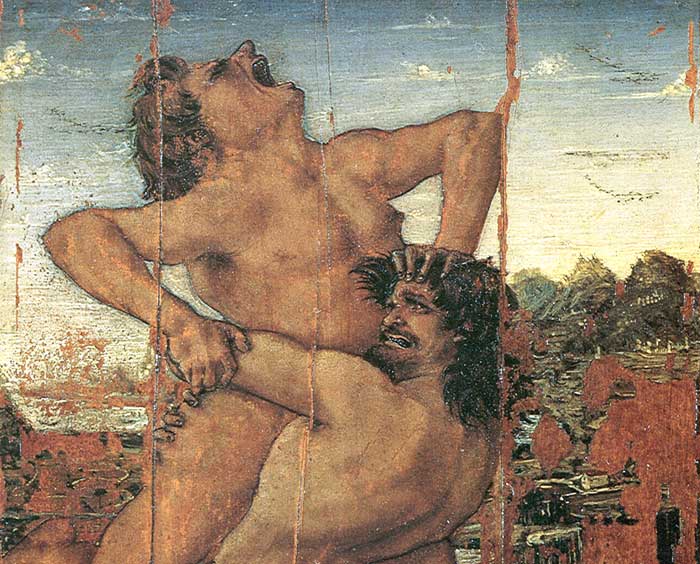

Hercules and Antaeus |

||

|

||

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Hercules and Antaeus (detail), c. 1478, tempera on wood, 16 x 9 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

||

| Although Hercules is a mythological figure, not a religious one, in Florence he was regarded as emblematic, indeed almost as a patron saint. He was both strong and virtuous, and he performed extraordinary deeds. Numerous Florentine paintings depicted Hercules, including a number by Pollaiuolo, several (now lost) done for the Palazzo Vecchio. Smaller replicas of these are in the Uffizi, exemplifying his style, characterized by figures with strong and well-defined contours, in vehement action, with expressive limbs. The small panel illustrates one of the labours of Hercules, deriving from the myth. The hero can be recognised by the attributes of the pelt of the Nemean lion (which he had defeated) and the knotty club. Hercules is crushing the giant Antaeus, holding him off the ground. The hero, clenching his jaws in the effort, crushes his enemy, who is struggling and yelling, against his own stomach. The figures stand out impressive against a landscape framed from a ‘bird’s eye’ view. For the episode of Hercules and Antaeus, cf. see description in the record on the small bronze on the same subject, also by Pollaiolo. The subject is taken from Apollodorus (2.5:11). On his way back from the Hesperides, Hercules engaged in a wrestling match with the giant Antaeus who was invincible as long as some part of him touched the earth, from which he drew his strength. Hercules held him in the air in a vice-like grip, until he weakened and died. Hercules is depicted with his arms locked round the waist of Antaeus, crushing the giant's body to his own. In pendant with the Hercules and the Hydra this little wood was maybe a decorative panel of furnishing: it had probably to reproduce the subject painted on large canvas in a room of the Florentine Medici palace at the time of Lorenzo the Magnificent. The struggle of Hercules against the giant Antaeus was an iconographical theme proper for Antonio del Pollaiuolo's style, suitable to express dynamic tension of limbs and muscles, as well as the anatomical study of human body. Hercules, the tutelary deity of Florence, the symbol of supreme civil virtues, the typical Florentine hero, is represented here in a fierce struggle which captures not only the movement of the bodies, but also the nervous tension of every muscle and the faces twisted into expressions of fatigue and horror. The subject was particularly popular with Pollaiuolo, given that this is the fourth or fifth version. The artist realized in fact the same subject again for Medici family, as the famous bronzetto now at the National Museum of Bargello in Florence.[2] |

||

|

||

Hercules and the Hydra |

||

|

||

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Hercules and the Hydra, c. 1475, tempera on wood, 17 x 12 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florenc e |

||

| This small panel, the companion-piece to "Hercules and Antaeus", refers to three panels representing the Labours of Hercules which Antonio del Pollaiuolo painted for Lorenzo de' Medici around 1460, lost works we know about only from later versions.

Here too is represented a ferocious fight between the hero, his body tensed into an agile, muscular mass and the legendary multi-headed monster. The outlines are very sharply defined, and the movement of nerves and tendons observed down to the last detail. Antonio del Pollaiuolo worked at time when thorough studies of anatomy were being made, and he therefore renders the human body realistically in its moments of greatest emotional excitement. The dramatic force of the episode is expressed in the hero's grimace of fatigue and horror, but also his certainty of victory. Behind the proudly barbaric figure blue rivers meander through a broad landscape of green and brown fields, the sky above an enamel blue. |

Hercules and the Hydra, c. 1475, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence |

|

Yale's painting depicts the centaur Nessus trying to abscond with Deianira, the wife of Hercules. Because the waters of the river were swollen, Nessus offered to carry Deianira across, but she realized he was trying to flee with her and shouted for help. Hercules shot at Nessus with a poisoned arrow, killing him. Before he died, however, Nessus persuaded Deianira that his blood was a love potion, and that she should smear a tunic with the blood and give it to Hercules. When Hercules put on the tunic, he was consumed with agony, and Deianira killed herself. The painting was given to Yale in 1871. It was originally on panel, probably part of a piece of furniture, perhaps something given to celebrate a marriage. In 1867, the painting had been removed from its panel support and transferred to canvas. When the painting was conserved in 1998, a sliver of wood, which was analyzed as cherry, a kind of wood often used for furniture, was found in the lining. Nothing about the commissioning of this painting is known. The mythological scene is shown not in an ancient setting but in the Arno valley, above the walled city of Florence. The course of the river Arno is discernible, leading down into the city. Just beyond the left hand of Deianira is Brunelleschi's famous dome of the Cathedral of Florence--finished just about the time Pollaiuolo was born--which is both exactly in the middle of the city and in the center of the composition. This is not the only painting by Pollaiuolo that shows Florence in the background--one of the best known of the others is the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (National Gallery, London)--manifesting the pride that he and others took in being Florentine. |

||

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian |

||

|

||

Antonio del Pollaiuolo and Piero del Pollaiuolo, The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (detail), completed 1475, London, National Galler y |

||

| This painting was made for the Pucci Chapel in the Santissima Annunziata in Florence. It is approximately contemporary with Verrocchio's Baptism of Christ, with which it shares stylistic features. It is among the outstanding paintings of the entire Quattrocento. The physically convincing foreground figures, the decisive fashion in which they plant their feet on the ground, their sturdy bodies, massive forearms and hands, and the muscles under energetic stress are typical of Antonio, as is the carefully studied anatomical structure with the bodies shown in frozen action. Antonio is an enthusiastic observer of ancient art, as evidenced by his frequent utilization of figural poses and types borrowed from classical sculpture. Although the painting is often attributed solely to Antonio, there is reason to believe that his brother Piero played a role in its execution. (The archers who shoot at the saint from behind and large portions of the landscape probably belong to Piero.)[4] Art in Tuscany | Antonio del Pollaiuolo and Piero del Pollaiuolo | Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian |

||

|

||

St Michael and the Dragon |

||

|

||

Antonio and Piero del Pollaiuolo, St Michael and the Dragon (detail), Florence, Museo Bardini

|

||

|

||||

Vasari Corridor, Florence |

Perugia |

Florence, Duomo

|

||

|

||||

Mediateca di Palazzo Medici Riccardi | Hercules and Antaeus, by Antonio del Pollaiolo The Mediateca Medicea is a digital archive relating to Palazzo Medici Riccardi, one of the most important buildings in Florence, which now belongs to the Provincial Authority and houses the administrative offices. The database is made up of different types of interrelated materials: texts, images, graphic reconstructions, and anything else which may contribute to a knowledge of the building in historic, architectural, artistic and cultural terms. The Mediateca extends and elaborates the subjects dealt with in the website www.palazzo-medici.it, with which it is connected. |

||||

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia article Antonio del Pollaiolo published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||

Holiday accomodation in Toscany | Podere Santa Pia |

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, December |

Podere Santa Pia |

||

|

||||

The abbey of Sant'Antimo |

Cortona |

Spoleto, Duomo |

||

|

||||

Crete Senesi, surroundings of Podere Santa Pia |

Val d'Orcia" tra Montalcino Pienza e San Quirico d’Orcia. |

Massa Marittima |

||