| |

|

Duccio di Buoninsegna was the most influential Sienese artist. His works include the Rucellai Madonna (1285) for Santa Maria Novella (now in the Uffizi) and the fabled Maestà, his masterpiece, for Siena's cathedral. Both represent landmarks in the history of Italian painting. His style reflected the influence of Cimabue and Byzantine art, though he introduced a warmth of human feeling that was comparable to that of Giotto in Florentine painting.

The Sienese School of painting flourished in Siena between the 13th and 15th centuries and for a time rivaled Florence, though it was more conservative, being inclined towards the decorative beauty and elegant grace of late Gothic art.[1]

Its most important representatives include Duccio, his pupil Simone Martini, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Domenico and Taddeo di Bartolo, Sassetta and Matteo di Giovanni.

In Duccio's art the formality of the Italo-Byzantine tradition, strengthened by a clearer understanding of its evolution from classical roots, is fused with the new spirituality of the Gothic style. Greatest of all his works is “Maestà” (1311), the altarpiece of Siena cathedral.

Duccio di Buoninsegna | Biography

|

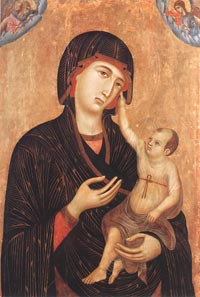

Probably the oldest version known is a small panel by Duccio of ca. 1280, with three Franciscan friars under the cloak. Here the Virgin sits, only one side of the cloak is extended, and the Virgin holds her child on her knee with her other hand.

The Madonna of the Franciscans shows structural articulation, and was probably part of a diptych or triptych intended for private worship, perhaps of a small group of Friars Minor. The features of the supplicating friars and the throne, a simple wooden seat placed obliquely to create an effect of perspective, reflect the teaching of Cimabue. Iconographically it follows the Madonna of Mercy type: while looking towards the spectator the Virgin holds back the edge of her robe the better to receive and protect the three kneeling friars, for whom the Child's blessing is intended. |

|

Duccio, Madonna of the Franciscans, ca 1280, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena

|

Duccio's Maestà

His most celebrated and only authenticated work is a large altar called the Maestà in the Siena cathedral. It was finished in 1311 and was carried to its place by a rejoicing populace. The enormous altarpiece is one of the landmarks of European painting.

Virtual reconstruction of the front panel of Duccio's Maestà

|

|

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maestà, 1308–1311, Tempera and gold on wood, 213 cm × 396 cm, Museo dell'Opera Metropolitana del Duomo, Siena

|

On the front it shows the Madonna and Child enthroned with saints and angels, while on the reverse (facing the choir, where the clergy sat during services) were more than fifty scenes of the life of Christ, incorporating urban views, landscapes, and interior settings of astonishing invention. While the main panel of the altar remains in the cathedral, the scattered predelle are now in the galleries of London and Berlin, the Frick Collection, New York City, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; and several private collections. Several other works are attributed to Duccio on stylistic grounds, including the design of stained-glass windows in the cathedral at Siena.

|

Maestà Altarpiece

|

|

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maesta Altarpiece, about 1308-1311, gold and tempera on panel, 370 x 450 cm, Siena, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo

|

The Maestà the high altarpiece painted by Duccio for the Cathedral in Siena, is arguably the greatest panel painting that has ever been produced. When it was completed, in 1311, the main panel must have looked physically more convincing, that is more tactile and more lifelike, than any painting in Siena that had preceded it, and the narrative panels must have seemed bewildering in their abundance and inventiveness. They evinced a variety of structure for which there was no precedent, and established almost all the compositional devices used by painters in Siena through the first half of the fourteenth century.

Like Giotto in the Padua frescoes, Duccio in the Maestà extended the expressive possibilities of painted narrative. On the unusually wide main panel are the Virgin and Child enthroned with saints and angels. Beneath it and above it are a narrative predella with scenes from the infancy of Christ, and seven scenes from the life of the Virgin. On the back there were originally forty-two scenes from the New Testament.

Both the fame of the Maestà, which drew large numbers of pilgrims to Siena, and Duccio's influence as a teacher had a long-lived impact on the style of Sienese art. While painters in nearby Florence adopted rounder, more realistic forms, most Sienese artists in the early fourteenth century continued to prefer Duccio's linear and decorative style, which used gold and strong color to create pattern and rhythm.[1]

The Maestà, his masterpiece, for Siena's cathedral. Originally carried through the streets of Siena in a religious ceremony, the multipaneled Maesta represented a major step forward in painterly style and narrative storytelling through visual art.

For a medieval artist a figure was in Maestà when represented frontally, sitting on a throne, at the peak of its own powers. Originally, such kind of representation was especially reserved to Cristo Re (King Christ) depictions, but during the 13th Century it became a pretty used way to depict Mary as well, whose 'sitting with the baby in her lap' image, shortly became the Maestà par excellence.

The Maestà for the high altar of Siena Duomo, painted either on the front and on the rear sides, always considered Duccio's masterpiece, dates back to the years of full artistic maturity of the painter. Duccio's Maestà was commissioned by the Siena Cathedral in 138 and it was completed in 1311. Today most of this elaborate double-sided altarpiece is in the cathedral museum but several of the predella panels are scattered outside Italy in various museums. It is probably the most important panel ever painted in Italy. It is certainly among the most beautiful.

The first element that comes to the attention of the "Maestà" is its extraordinary compexity: a work of more than four meters each side, painted on both sides, glittering with gold and gorgeous colors.

The whole of the front of the main panel is occupied by a scene of the Virgin and Child in majesty surrounded by angels and saints, and corresponding to this on the back there are twenty-six scenes from Christ's Passion. Originally there were subsidiary scenes from Christ's life above and below the main panel. The whole work is a superb standard of craftsmanship, and the exquisite colouring and supple draughtsmanship create effects of great beauty.

The Maestà remained on the high altar of the Duomo since 1506, when Pandolfo Petrucci, leader of the town at the time, wanted it to be replaced with the big bronze tabernacle of the Vecchietta (in Santa Maria della Scala before) that survived to the new preparation of the chorus zone made by Baldassarre Peruzzi in 1536. Duccio's painting was then hung to a wall of the left transept where it remained until 1771, when the two faces of the work were divided: the front part was placed in Sant'Ansano chapel, the rear part in San Vittore chapel; at the same time, the small paintings composing the predella and the crowning, removed and moved to the sacristy, began to be sold to collectors and foreign museums. When the 'Maestà' was finally moved to the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo of Siena, in 1878, there were nine elements of the predella, two of the crowning and all of the spikes with the angel figures missing.

Duccio’s magnificent Maestà was installed in June 1311 after a triumphant procession through the streets of Siena. Priests, city officials, and citizens were followed by women and children ringing bells for joy. Shops were closed all day and alms were given to the poor. Completed in less than three years, the Maestà was a huge undertaking for which Duccio received 3,000 gold florins—more than any artist had ever commanded. Nevertheless, Duccio, like all artists of his time, was regarded as a craftsman and was often called on to paint ceiling coffers, parade shields, and the like. Not until the middle and later fourteenth century did the status of artists rise.

Duccio signed the main section of the Maestà. His signature, one of the earliest, reads: “Holy Mother of God, be the cause of peace for Siena and life for Duccio because he painted you thus.” This plea for eternal life—and perhaps fame—signals a new self-awareness among artists. Within a hundred years signatures become commonplace.

Art in Tuscany | Duccio di Buoninsegna | The Maestà

|

|

|

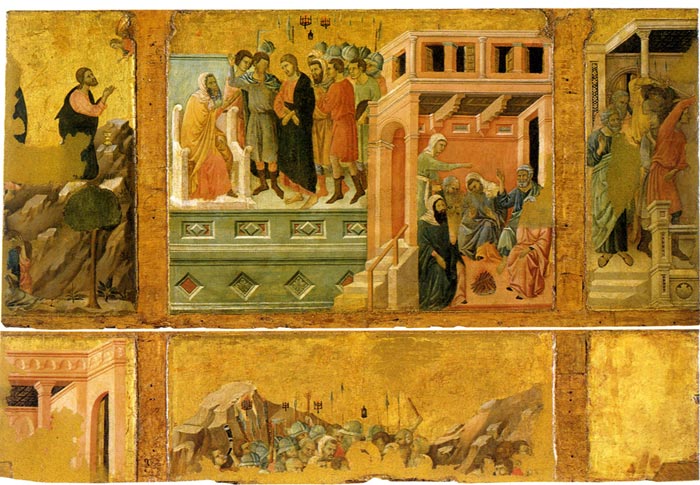

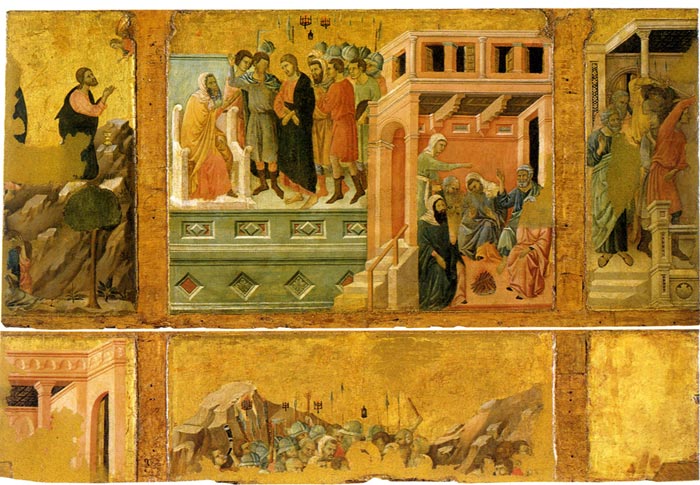

The two predellas were each painted on a horizontally laid piece of wood, and could therefore be taken apart easily. Several individual scenes found their way to museums or private collections.

The predella pictures underneath are devoted to the childhood of Christ, with portraits of prophets separating individual scenes (the Annunciation, the Prophet Isaiah, the Birth of Christ, the Prophet Ezekiel, the Adoration of the Magi, the Prophet Solomon, the Presentation in the Temple, the Prophet Malachi and the Massacre of the Innocents).

The episodes on the reverse side, originally numbered 43 in total, were intended for spectators in the presbytery, who could get closer to the panel than the faithful who congregated in the main body of the church. The crowning panels of the reverse side depict scenes after His resurrection. The pictures of the predella on the reverse side depict the temptation and miracles of the Son of God.

In the Temptation on the Mount the majestic grandeur of all the kingdoms of the world is depicted with superb skill. The imaginative power of the architecture, in clear and luminous shades, is extraordinary: loggias and battlements alternate with round belltowers, red-tiled roofs and Gothic windows, all protected by solid encircling walls. The imaginative power of the architecture, in clear and luminous shades, is extraordinary: loggias and battlements alternate with round belltowers, red-tiled roofs and Gothic windows, all protected by solid encircling walls.

Temptation on the Mount, Tempera on wood, 43 x 46 cm, Frick Collection, New York |

|

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maestà, Temptation on the Mount, Frick Collection, New York |

| |

|

|

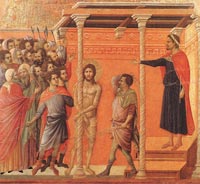

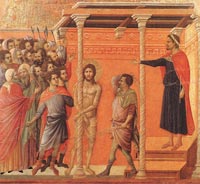

Considering that the Flagellation is barely mentioned in the gospels, the descriptive details show remarkable inventiveness, aimed at illustrating each moment of the Passion. The figure of Pilate disobeys all the rules of perspective: although obvious from the seat on which he is standing that he is inside the building, he manages to stretch his arm in front of the pillar, in a position parallel to the horizontal level of the floor.Cimabue appears to have been a highly-regarded artist in his day. While he was at work in Florence, Duccio was the major artist, and perhaps his rival, in nearby Siena.

History has long regarded Cimabue as the last of an era that was overshadowed by the Italian Renaissance. In Canto XI of his Purgatorio, Dante laments Cimabue's quick loss of public interest in the face of Giotto's revolution in art:[3]

O vanity of human powers,

how briefly lasts the crowning green of glory,

unless an age of darkness follows!

In painting Cimabue thought he held the field

but now it's Giotto has the cry,

so that the other's fame is dimmed.

Art in Tuscany | Duccio di Buoninsegna | The Back Panels of the Maestà |

|

Flagellation, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena |

| |

|

|

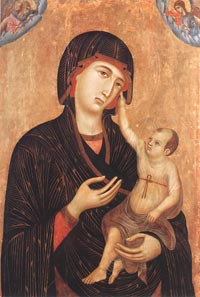

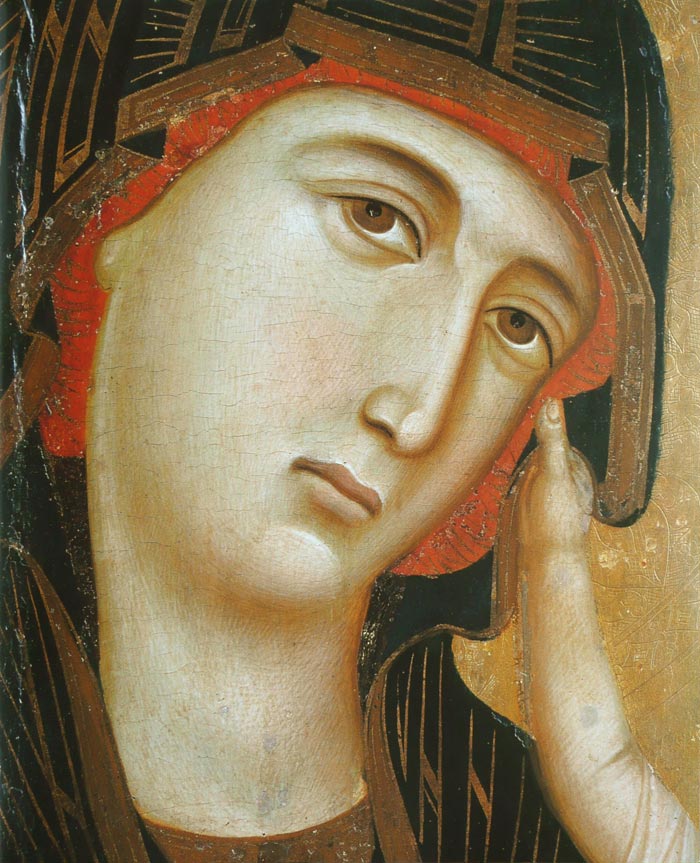

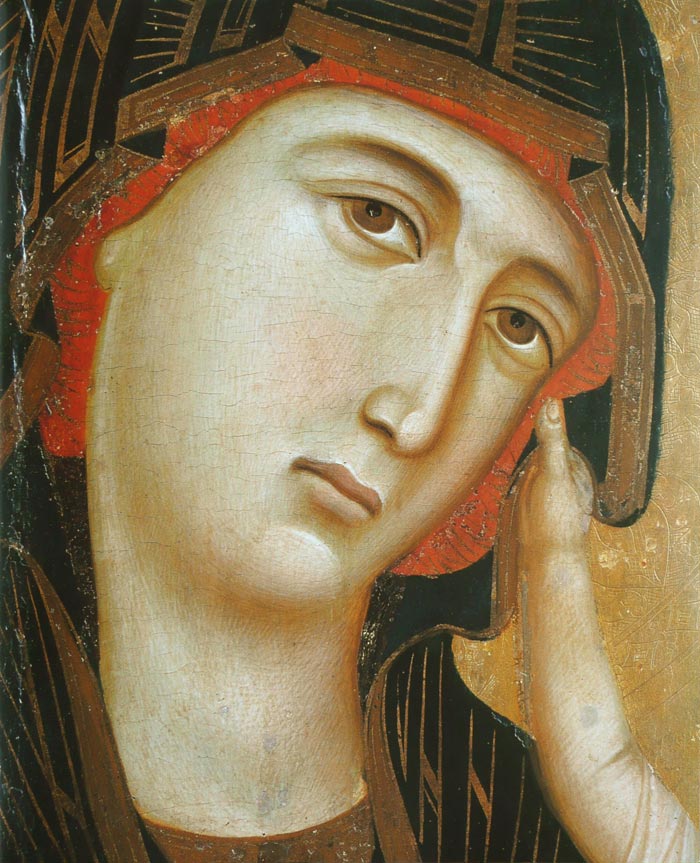

The Crevole Madonna

|

The Crevole Madonna and the Madonna of Buonconvento are unanimously considered the earliest works attributable to Duccio. The basic approach of the two paintings is of evident Byzantine tradition: the elegant stylization of the hands, the typical downward curving nose, the red maph?rion under Mary's veil, the dark drapery animated by shining gilded lines. New details appear, to a lesser extent in the Buonconvento Madonna and repeated with greater confidence in the Crevole painting, such as the subtle play of light on the Virgin's face, over her chin and cheeks, and a clear attempt at plasticism in the folds of the garment around the face.

In Duccio's art the formality of the Italo-Byzantine tradition, strengthened by a clearer understanding of its evolution from classical roots, is fused with the new spirituality of the Gothic style. Greatest of all his works is “Maestà” (1311), the altarpiece of Siena cathedral.

The more carefully considered compositon of the Crevole Madonna shows a faint but decided French influence: the elegant forms of the angels in the upper corners, the veiled transparency of the Child's garment, held up by a curious knotted cord, and most of all, the intimate gesture of the Infant Jesus, held in a tender embrace.

|

|

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Madonna with Child and Two Angels (Crevole Madonna), 1283-84, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena

|

| The Crevole Madonna and the Madonna of Buonconvento are unanimously considered the earliest works attributable to Duccio. The basic approach of the two paintings is of evident Byzantine tradition: the elegant stylization of the hands, the typical downward curving nose, the red maphórion under Mary's veil, the dark drapery animated by shining gilded lines. New details appear, to a lesser extent in the Buonconvento Madonna and repeated with greater confidence in the Crevole painting, such as the subtle play of light on the Virgin's face, over her chin and cheeks, and a clear attempt at plasticism in the folds of the garment around the face.

The more carefully considered compositon of the Crevole Madonna shows a faint but decided French influence: the elegant forms of the angels in the upper corners, the veiled transparency of the Child's garment, held up by a curious knotted cord, and most of all, the intimate gesture of the Infant Jesus, held in a tender embrace.

|

|

Madonna with Child and Two Angels (Crevole Madonna), 1283-84, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena

|

Madonna and Child (also known as the Stoclet Madonna or Stroganoff Madonna) is a panel painting by Italian medieval artist Duccio di Buoninsegna. Painted in tempera with gilding on wood panel around the year 1300, it depicts Mary, the mother of Jesus holding the infant Jesus.

In November 2004 the painting was purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (Met) for an undisclosed sum, reported to be in excess of 45 million USD, the most expensive purchase ever by the museum. It was the first work by Duccio acquired by the Met, which bought the painting from members of the Stoclet family in Belgium, in order to close a gap in its permanent collections of painting. Works by Duccio, who is considered one of the pre-eminent painters of Sienese medieval painting, are extremely rare, with only a dozen or so known to survive; before the Met's purchase this was the last piece still in private hands. The painting is one of the few Duccios known to be created as an individual work of art, and not part of an ensemble.[4] |

|

Madonna and Child

Madonna and Child (also known as the Stoclet Madonna), c. 1300, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

| |

|

|

Duccio is considered to have had a major influence on the formation of the International Gothic style, and to have influenced Simone Martini and the brothers Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti, among others. In Siena's Palazzo Pubblico, under Simone Martini's famous Guidoriccio da Fogliano, is the well-executed fresco Surrender of Giuncarico Castle which has been attributed to Duccio Buoninsegna and is dated around 1314, making it one of his last works.[2]

The Surrender of the Castle of Giuncarico shows a man in green about to hand over his sword to the Sienese general. In the background is his castle and a village on a rocky hilltop. Duccio's Surrender inspired his pupil Simone Martini's landscape of Guidoriccio da Fogliano.

Simone Martini's "Guidoriccio da Fogliano": A New Appraisal in the Light of a Recent Technical Examination, Joseph Polzer, Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen, Bd. 25, (1983), pp. 103-141

Art in Tuscany | The Sala del Mappamondo (the World Map Room) and the lost wheel map of Ambrogio Lorenzetti

|

|

Duccio di Buoninsegna, La consegna del Castello di Giuncarico

|

To Duccio himself is attributed not only the late mural with the "Castello di Giuncarico" (dating back to 1314 circa), rediscovered about twenty years ago on a wall of the Sala del Mappamondo in the Palazzo pubblico in Siena, but also (as Miklos Boskovits and David Wilkins sensed) the even older serie of the Bardi chapel in Santa Maria Novella in Florence, stylistically very close to the 'Madonna Rucellai'. On the example of the craftsman, many artists of his group made fresco decorations both in Siena (San Martino, Santa Maria dei Servi) and in the countryside (San Lorenzo al Colle Ciupi, near Monteriggioni, Casole d'Elsa...).

Very recent is the sensational discover, in the rooms of the so called Crypt of the Sienese Cathedral, of a complete serie of frescoes, made by a group of Sienese artists which can be dated back to 1270-1275 circa.

Remained hidden in the dark for centuries this serie, which is going through a very hard and delicate restoration process, presents gold and colours in an excellent preservation state, highly superior to every coeval mural painting known.

|

|

|

The Rucellai Madonna was commissioned on April 15, 1285, by the Confraternity of the Laudesi of S. Maria Novella in Florence.

Infusing new life into the stylized Byzantine tradition, Duccio initiated a style intrinsic to the development of the Sienese school — the expressive use of outline. The use of line varied from a vigorous quality in his rendering of narrative scenes to a lyrical and majestic tone in his portrayal of the Madonna and angels. In 1285 he was commissioned to paint a Madonna for Santa Maria Novella, Florence, today identified with the Rucellai Madonna (Uffizi).

The picture's name derives from the Rucellai Chapel of Santa Maria Novella where it remained, after being moved to several different places inside the church, from 1591 to 1937, the year of the Giotto exhibition. It was then transferred to the Uffizi. The panel was commissioned in 1285.

The painting has been the subject of much controversy among critics. In the fifteenth century it was thought to be the work of Cimabue, and this attribution, supported by Vasari, was accepted until the beginning of present century. The design of the frame decorated with roundels, the three pairs of angels flanking the throne and the sweeping gesture of the Child's blessing hand, show undeniable similarities to Cimabue's Maestà, now in the Louvre but at that time in the Church of San Francesco in Pisa. |

|

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Rucellai Madonna

|

This work comes from the front predella, the separate horizontal band of narrative scenes at the base of the great Maestà altarpiece that depicts Mary, the patron saint of Siena, in majesty with angels and saints. A contract of 1308 states that the huge altarpiece for the cathedral of Siena was to be painted entirely by Duccio di Buoninsegna; it is probable, however, that the artist took on assistants to help carry out the project.

In the Nativity, Duccio employed conventional Byzantine elements, such as the cave setting, the glowing colors, and the multi-scene composition. Mary is shown in the usual Byzantine manner — larger than the figures around her yet — her large size also underscores the importance the Virgin held for the Sienese. The bracketing side panels portray Old Testament prophets holding scrolls that foretell the birth of Christ.

Duccio's unique contribution to the Byzantine style is his use of elegantly flowing lines, most evident here in the drapery folds and mountain ridges. The soft, undulating brushstrokes downplay the austerity of the earlier style, as do the sensitive rendering of the Virgin's face and the individual characterizations of Isaiah and Ezekiel, expressing a true sense of human feeling.

|

|

Duccio di Buoninsegna, c. 1255 - 1318, The Nativity with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, Washington National Gallery of Art |

The Madonna delle Grazie, attributed to Duccio di Buoninsegna is located in the Duomo di San Cerbone, Massa Marittima.

The cathedral, dedicated to St. Cerbone, was built between the end of the XII century and the first half of the XIII century. Numerous works of art are kept inside the church. The chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary (to the left of the presbytery) currently keeps the fragmentary Maestà on the inside. It is the most precious work of art in the whole building and it was painted on wood panel around the year 1316 by the famous Sienese painter Duccio di Buoninsegna and his shop.

It was originally destined to the high altar of the Dome and it represents the Madonna col Bambino (the so-called Madonna delle Grazie) on the front side and the Scenes from the Passion of Christ on the reverse side. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Storie della Passione di Cristo, Workshop of Duccio di Buoninsegna about 1311-1324, gold and tempera on panel,

161.5 x 101.5 cm, Massa Marittima, Duomo di San Cerbone

|

This is a fragment of the reverse side of the Maesta altarpiece. It represents scenes from the Passion of Christ: Crucifixion and Christ before Pilate.

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Vasari and Duccio di Buoninsegna

Duccio di Buoninsegna's Maestà, commissioned by the city of Siena in 1308, is his most famous work.

Duccio painted the work with assistants in a studio located on Via Stalloreggi, very close to the Duomo di Siena. The painting was installed in the cathedral of Siena on 9 June 1312 after a procession of the work in a loop around the city.

The fame of the Maesta did not entirely escape Vasari's notice, for he must have known the chronicled accounts of its triumphant installation. Always keen for a story that testified to the high esteem artists could achieve by their genius, and an unapologetic protagonist of Florence as the fountainhead ofItalian painting, he adapted the story to suit one of his heroes, Cimabue (ca. 1240 - after 1302), the teacher of Giotto, and

a painting he identified as marking the turning point from the Byzantine to a more modern, naturalistic style. The picture in question is the celebrated Ruccellai Madonna, which confronts visitors to the first gallery of the Uffizi in Florence[5].

|

|

| Frederic Leighton, Cimabue's Celebrated Madonna is carried in Procession through the Streets of Florence (detail), Oil on canvas, 222 cm × 521 cm, The National Gallery, London [1]

|

The altarpiece was commissioned in 1285 by a Dominican fraternity, the Company of Laudesi, and although Vasari attributed the panel to Cimabue it is now known to be by Duccio, who is named in the contract. In Leighton’s imaginative reconstruction Cimabue, wearing white and crowned with a laurel wreath, leads his pupil Giotto by the hand. On the far right Dante, leaning against a wall with his back to the viewer, watches the procession. The mounted figure bringing up the rear is probably King Charles of Anjou. Various other artists make up the rest of the crowd carrying the trestle upon which the altarpiece sits[6].

|

|

Art in Tuscany | Italian Renaissance painting

|

The best available monograph on Duccio is in Italian, Cesare Brandi, Duccio (1951). There is nothing comparable in English. Enzo Carli's book for the Astra Aréngarium Series, Duccio (1952), is available in English and includes a remarkable amount of information; the reproductions are poor. Evelyn Sandburg-Vavalà's chapters on Duccio and his school in Sienese Studies: The Development of the School of Painting of Siena (1953) are excellent for an understanding and appreciation of Duccio's art.

|

Vasari, Lives of the most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, Vol 2, Duccio di Buoninsegna

|

Art of Duccio di Buoninsegna | www.wga.hu

|

Duccio di Buoninsegna, The beginnings of Sienese painting

|

| |

With the impressive exhibition “Duccio: The Beginnings of Sienese Painting“ the city of Siena rediscovered one of its most famous artists: Duccio di Buoninsegna, the founder of the Sienese school of painting. Active from 1278 to his death in the summer of 1319, he represents a link between the outgoing Romanesque style and the incoming Tuscan Gothic.

www.duccio.siena.it

|

Simone Martini's "Guidoriccio da Fogliano": A New Appraisal in the Light of a Recent Technical Examination, Joseph Polzer, Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen, Bd. 25, (1983), pp. 103-141

|

Duccio's Madonna and Child | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Tomkins, C. (July 11 & July 18, 2005). "The Missing Madonna: The story behind the Met's most expensive acquisition". The New Yorker.

|

Art in Tuscany | Duccio di Buonsegna

Frederic Leighton, Cimabue's Celebrated Madonna is carried in Procession through the Streets of Florence, The National Gallery, London

|

|

|

|

| [1] Siena in the 1400s | Painting in Siena in the 14th and Early 15th Centuries | National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

Only about fifty miles separate Florence and Siena. However, if we compare Florentine pictures to these painted during the same period in Siena, we might believe we have stepped through time, not space. The gold backgrounds, the rich pattern and tooled detail, the saints and angels standing in formation—all seem more at home in the late Middle Ages than in the early Renaissance.

Though they did not rush to embrace them, Sienese artists were aware of the innovations in Florentine painting. They experimented with its naturalism, its solid, three-dimensional forms, its one-point perspective, and eventually its secular outlook—but their paintings remain distinctly Sienese. On some level artists may have eschewed outside innovations as their own city's economic and political fortunes declined. Certainly their patrons continued to expect works that were in keeping with an older Sienese tradition. For more than one hundred years the powerful legacy of early fourteenth-century masters like Duccio and Simone Martini sustained a preference for color and pattern, refinement and decoration. These artists' venerable images decorated the city's churches and public buildings, remaining part of the fabric of life. Saint Bernardino, a contemporary of the artists here, exhorted listeners to emulate the humility of a Virgin painted by Simone Martini. Such authority discouraged radical departures in style.

Devotion to the Virgin—and her images—was strong. She was Siena's patron saint and appeared on the city's coins. Her veneration had an important civic component, and in Siena artistic patronage was a largely civic enterprise. Into the 1400s many commissions were still communal, funded by the city or religious fraternities. Humanism, which had fueled demand for secular subjects and increased private patronage in Florence, came late to Siena. |

|

|

|

| [2] No reliable information exists on Duccio's artistic output during the years which elapsed from the completion of the Maestà up till his death some time between the end of 1318 and the first half of 1319. During recent restoration work (1979-80) in the Sala del Mappamondo of the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, a new fresco was discovered below the imposing Guidoriccio da Fogliano by Simone Martini, representing a castle on a hill and two people in the foreground. The attempt to discover the identity of the unknown author of this work has given rise to much controversy among critics. Duccio, Pietro Lorenzetti, Memmo di Filippuccio, Simone Martini were suggested. However, Duccio is known principally as a painter of panels and the problem remains unsolved. The fresco, of outstanding executive quality both in the skilful choice of descriptive detail and in its overall coherence, was badly damaged by the Mappamondo, a large, revolving, circular painting by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, which was placed on top of it in 1345. |

|

| [3] Purgatio XI, cited in the Cenni di Petro Cimabue article in the Catholic Encyclopedia |

|

[4] The painting is sometimes called the Stoclet Madonna, after the family name of Adolphe Stoclet, its second recorded owner, who was a Belgian industrialist in the early 20th century. The Met refers to the painting as the Stroganoff Madonna after its first recorded owner, Count Grigorii Stroganoff, a serious collector of early Italian paintings who died in Rome in 1910. Stoclet acquired the painting following Stroganoff's death. After Stoclet and his wife died in 1949, the painting was willed to their son, Jacques. His four daughters inherited the painting from his widow Anny, who died in June 2002[1]. Through a sale arranged by Christie's, the daughters transferred ownership to the Met.

See also:

Tomkins, C. (July 11 & July 18, 2005). "The Missing Madonna: The story behind the Met's most expensive acquisition". The New Yorker.

[5] Keith Christiansen, Duccio and the Origins of Western Painting, Metropolitan Museum of Art (February 3, 2009), New York, p. 22.

[6] The Royal Collection Trust | FREDERIC LEIGHTON (1830-96), Cimabue's Madonna Carried in Procession

|

Our knowledge of Duccio’s life comes entirely from documents relating to his activity as a painter, his ownership of property, and fines for misdemeanors. For example, in 1279 and 1302 he was fined for trespassing. There are records in 1302 of his refusal to fulfill his military obligations and of a further misdemeanor. Like all painters of the day, Duccio undertook a wide variety of tasks, ranging from decorating the account books of the fiscal branch (the Biccherna) of Sienese government to designing the enormous stained glass window in the apse of the cathedral of Siena (1287–88), to painting major altarpieces and small panels for private devotion. Only about a dozen independent works by the artist survive. Of his seven children, three became painters.

Beginnings

Traces of Duccio’s association with Cimabue remain in the large round stained-glass window of the choir of the Siena cathedral, for which Duccio made the designs. This work was commissioned between 1287 and 1288 and is the earliest known example of stained glass produced by an Italian.

There is little documented information about Duccio's life and career. In large part his life must be reconstructed from the evidence of those works that can be attributed to him with certainty, from the evidence contained in his stylistic development, and from the learning his paintings reveal. Duccio's father was from the town of Buoninsegna, near Siena, but at the time of Duccio's birth he lived in the town of Camporegio. He is first mentioned in 1278, when the treasurer of the commune of Siena commissioned him to decorate 12 strongboxes for documents. The following year he was given the task of decorating one of the wooden covers of the account books of the treasury. That Duccio was doing work more appropriate for an artisan than an artistmust not lead one to assume that even at this time he was only a beginner. It is known that services of this type were requested, both in Siena and in Florence, of already established painters. Further, the fact that he was designated as “painter” and was working for himself demonstrate that he was a mature and independent artist by 1278. In 1280 Duccio was fined the large sum of 100 lire by the commune of Siena for some unrecorded misconduct. This was the first of a considerable number of fines that the artist incurred at various times and for various reasons, and they suggest that he was of a restless and rebellious temperament. He was fined more than once for nonpayment of debts; in 1295 he was penalized for refusing to pledge allegiance to the head of the popolo party; in 1302 for not appearing for military duty; and in the same year for what appears to have been practicing sorcery.

The “Madonna Rucellai.” On April 15, 1285, the Compagnia dei Laudesi, or singers of praise, of the Virgin Mary at the church of Sta. Maria Novella in Florence, commissioned “Duccio di Buoninsegna, painter of Siena” to paint a great altarpiece that was to represent the Madonna and Child together with otherfigures. For the work he was to be paid 150florins, but if the painting, which had to be “a most beautiful picture” and had to havea gold border, was not satisfactory, the artist would receive no reimbursement. Despite the fact that this employment contract, preserved in the State Archives of Florence, came to light in 1790 and was published in 1854, it was only in 1930 that it was indisputably determined that the document referred to the Madonna of Sta. Maria Novella, now called the “Madonna Rucellai.” From the time of Giorgio Vasari, a minor Florentine Renaissance painter who was the earliest, and probably the most influential, biographer of early Italian artists, this altarpiece, which was the largest yet painted, was considered to be a masterpiece of the Florentine painter Cimabue. Vasari's attribution, whereas it was probably due in part to a desire not to deprive the Florentine school and its founder of credit for so brilliant a work, was accepted almost unanimously until the present century because of strong similarities to thework of Cimabue in the “Madonna Rucellai.” Some recent critics, no longer able to deny that the work is by Duccio, have concluded that he was a pupil, and in all essentials of his art even an imitator, of Cimabue.

The problem of the relative influence of Cimabue upon Duccio is critically very complex. The “Madonna Rucellai” shows affinities with the work of Cimabue in the type of the Virgin, in the serious and robust Child, and in the faces of the six adoring angels; nevertheless, it reveals strikingly new stylistic innovations in the softness of the angels set in midair, in the elegant and subtle lines, in the first feeling of French Gothic animated sweetness and spirituality, and in the light and shade modulation of the free-flowing, clear brush strokes.

There is no doubt that his knowledge of Cimabue's work was one of the components of Duccio's style at this time, but it was not the predominant, nor even the earliest influence; very probably Cimabue's influence was a late insertion into a personal style that had already evolved within the framework of the well-developed Sienese tradition. In the years between 1260 and 1280, largely due to the inspiration of its magnificent cathedral, Siena had emerged as one of the most vital centres of art in Italy. A remarkable successionof altarpieces by Sienese painters testifies to the simultaneous work of a number of artists, some of whom possessed quite distinct personalities. The variety of orientations of these painters shows that they did not work in provincial isolation but were sensitive to the diverse influences of the age, including Cimabue.

Duccio certainly studied these painters and was influenced by them. Notably evident in his style are the influence of the older painter Guido da Siena with the serene dignity of his figures, permeated by lyrical tenderness and grace, in the now-fading stylized postures of the Byzantine tradition, and of the master of the “St. John the Baptist Altarpiece” in the Pinacoteca Nazionale of Siena, with his complex Byzantine iconography and his vivid, dense colouring. Duccio was ableto draw from sources outside Siena as well: from the combination of linear stylization and Hellenistic types that characterized the illustrations of books imported from Constantinople and also from contemporary French Gothic miniatures, with their lively tone and lyrical, animated stylizations of clothing and gesture. Duccio may also have travelled to Florence in his early years, coming into contact with Cimabue, but such an explanation is not entirely necessary to account for the formation of his style. In fact, in Duccio's only certain work prior to the “Madonna Rucellai,” echoes of Cimabue are even less apparent than in the Rucellai altarpiece. The conclusion that Duccio was nothing more than a follower of Cimabue at the time he painted the “Madonna Rucellai” is implausible and overlooks the originality, as well as the excellence, of the work. If, in fact, he was in 1285 entrusted with a work of such significance at Florence, his reputation must have already been establishedand have spread beyond the confines of his native Siena.

Later commissions

Traces of Duccio's association with Cimabue remain in the large round stained-glass window of the choir of the Siena cathedral, for which Duccio made the designs. This work was commissioned between 1287 and 1288 and is the earliest known example of stained glass produced by an Italian.

Numerous documents attest to Duccio's action in Siena during the 20 years following the creation of the “Madonna Rucellai.” He was by now the leading painter of the city and as such executed in 1302 an altarpiece, now lost, for the altar of the chapel of the Palazzo Pubblico, the city hall. During this period, some unsigned and undocumented altarpieces appeared, and some of these are certainly Duccio's work; the most significant of these is a small altarpiece representing the Virgin enthroned with angels andcalled “The Madonna of the Franciscans” because of the three monks kneeling at the foot of the throne. In this work a developed Gothic style appears in the curving outlines, which give an exquisite decorative effect.

The work in which the genius of Duccio unfolds in all its brilliant fullness and the one to which the painter owes his greatest fame, however, is the “Maesta,” the altarpiece for the main altar of the cathedral of Siena. He was commissioned to do this work on Oct. 9, 1308, for a payment of 3,000 gold florins, the highest figure paid to an artist up to that time. On June 9, 1311, the whole populace of Siena, headed by the clergy and civil administration of the city, gathered at the artist's workshop to receive the finished masterpiece. They carried it in solemn procession to the accompaniment of drums and trumpets to the cathedral. For three days alms were distributed to the poor, and great feasts were held. Never before had the birth of a work of art been greeted with such public jubilation and never before had there been such immediate awareness that a work was truly a masterpiece and not just a reflection of the religious fervour of the people. Duccio himself was aware of the work's significance; he signed the throne of the Virgin with an invocation that was devout yet proud for the time: “Holy Mother of God, grant peace to Siena, and life to Duccio because he has painted you thus.”

The “Maesta” is in the form of a large horizontal rectangle, surmounted by pinnacles, and with a narrow horizontal panel, or predella, as its base. It is painted on both sides. The entire central rectangle of the front side is a single scene showing the Madonna and Child enthroned in the middle of a heavenly court of saints and angels with the four patron saints of Siena kneeling at their feet. The back is subdivided into 26 compartments that illustrate the Passion of Christ. The front and back of the predella contain scenes of the infancy and the ministry of Jesus, and the pinnacles, crowning the entire work, represent events after the Resurrection. In all, there are 59 narrative scenes.

The rigorous symmetry with which the groups of adoring figures at the sides of the Virgin are arranged in the imposing scene of the central panel is inspired by compositions of the Byzantine tradition and gives evidence of Duccio's keen architectural sensibility by its power to draw attention to the “Maestà” as the true focal point of the cathedral's spatial and structural organization. Like elements of a living architecture, the 30 figures, through the slightest of gestures and turnings of the head, are intimatelyrelated, their positions repeated to give a feeling of intense lyrical contemplation. The consonance of feeling that arises from this contemplation gives the facial features of each a distinct, spiritual beauty, reminiscent, especially the faces of the angels, of the more idealistic creations of Hellenistic art. The Madonna, slightly larger than the other figures, seated on a magnificent and massive throne of polychrome marbles, inclines her head gently as if trying to hear the prayer of the faithful. Duccio thus succeeds in reconciling perfectly the Byzantine ideal of power and dignity with the underlying tenderness and mysticism of the Sienese spirit. The scenes in the predella, pinnacles, and back are filled with the Byzantine iconographic schemes from which Duccio finds it difficult to detach himself, and they are developed with a deeper concern for their narrative significance. The scenes are not, however, merely descriptions or chronicles. They include many touches from daily life, which provide a lyrical synthesis that harmonizes the character and gestures of the figures with their landscape and architectural surroundings.

Last years

Only scanty bits of information are available about the few years that Duccio lived after the completion of the “Maesta.” He had a prosperous workshop from which other works emerged, but they seem to have been executed in great part by students. His financial condition must have been quite sound because by 1304 he bought a vineyard in the neighbourhood of Siena. Nevertheless, in 1313 he was once again deep in debt. At death he was survived by his wife, Taviana, and seven children. At least two of his children, Galgano and Giorgio, were painters, but nothing is known about their work or their merits. The identity of one of his direct followers is known, his nephew Segna di Buonaventura.

Enzo Carli (Encyclopaedia Britannica)

|

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Cipresses between Montalcino and Pienza |

|

Podere Santa Pia |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Siena in the Middle Ages

Siena reached the height of its splendour in the Middle Ages, when in 1147 it became an independent comune after a century of rule under the bishop. After gaining its independence, the city adopted an expansionistic policy, considerably increasing its domains. But the development and riches brought by trade also accompanied social conflict, which soon developed into a bloody struggle for supremacy between Guelphs and Ghibellines, the two opposing factions that supported respectively the Church and the Empire. Due to its Ghibelline status, Siena went to war against neighbouring Florence, which supported the Pope. Its troops gained a formidable victory against the Florentines at the Battle of Monteperti, on September 4th 1260. Only nine years later, however, Siena was in turn defeated by Florence and the city passed into Guelph hands, heralding a new government and a long period of prosperity.

Siena reached its golden age of architecture during the 14th century, when the city was able to erect many of the most important buildings that survive to this day. These include the Campo, the Palazzo Pubblico (then known as Palazzo dei Signori in reference to the city’s ‘Nine’ governors) the Duomo and the Torre del Mangia. This was also the period in which Senese art flourished, with masterpieces such as Duccio’s Maestà. At this time the city invested enormously in costly projects such as the building of the fortified village of Paganico or the port at Talamone.

But Siena was also known for its lavish feasts and tournaments, such as the Gioco dell’Elmora, in which young men fought one another with clubs and stones. This game was supplanted in 1291 with the Gioco delle Pugna, in which the contenders fought with their hands covered by a wicker structure, or other games such as the Pallonata or the Bufalata. Piazza del Campo was frequently used for a variety of horse races, which developed over the centuries into the city’s best known event, the Palio.

In emulation of ancient Rome, Siena wished to underline its independence. But the great Plague of 1348 decimated the city’s population, bringing decadence and financial collapse. In the fifty years that followed, the city underwent considerable political upheaval, famine and rebellion, which culminated in the end of the government of the ‘Nine’ and loss of independence when in 1390 the city was annexed to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.

Despite losing their independence, the people of Siena retained their proverbial courage and cunning. St Catherine of Siena, who during her lifetime was called Caterina Benincasa, died in 1380 after playing an instrumental role in bringing back the Papacy to Rome from its exile in Avignon, thereby proving that the city had not altogether lost its political influence.

Siena in the Renaissance

Just as it reached its greatest political, financial, social and artistic splendour during the 14th century, during the following century the city of Siena appeared destined to live out its final twilight.

With the end of the government of the Nine, Siena entered a period of political instability. In 1403, the ruling Monte dei Dodici was accused of trying to seize definitive power and deposed. There followed a time during which the city was ruled by the Monti Popolari, known as the “Tripartito”, which remained in power until 1480.

During the Renaissance, Siena was a relatively small town of about 15,000 inhabitants. The Senese community as a whole was heavily involved in the duties of public office and each individual had a strong sense of personal duty towards the public administration. This explains why many of the city’s great art treasures were commissioned by the city and not by noble families, whose members were far too busy carrying out their functions as Podestà. The Opera del Duomo at the time grew into a kind of artistic and architectural commission that administered the Palazzo della Mercanzia and the Cappella di Piazza.

Although in many ways a good thing, the great sense of civic duty that characterised the Senese meant that a good deal of animosity would spring up between any number of people and factions on any number of issues concerning the public administration. A remarkable man named Pandolfo Petrucci was thus able to take advantage of such a chaotic situation, gradually developing his influence to such an extent that he became the ruler of Siena in all but name. An able political manipulator, Petrucci effectively governed the city for about twenty years, from 1400, without actually doing away with its traditional government bodies. Under Petrucci’s rule the architecture of Siena developed considerably. Petrucci erected his own opulent palazzo, naming it Palazzo del Magnifico, but his untimely death when still a young man plunged the city into a new period of political upheaval.

Weakened by internal strife, Siena became an easy prey in the territorial designs of the great European powers such as France and Spain. In 1553 Florence allied itself with the Holy Roman Empire and invaded. Siena, which at the time numbered less than 10,000 inhabitants, fell the following year, passing under the direct rule of Cosimo De’ Medici in 1557, who celebrated by ceremonially entering the city and watching a play in the Palazzo Palazzo Pubblico. From this moment onwards, Siena followed the fortunes of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and its ruling Medici family.

On a constitutional level, Siena was not annexed to the Florentine state, retaining its Republican Statute (1544-45) as a newly formed state until the second half of the 16th century with the reforms introduced by Peter Leopold.

Art in Tuscany | Sienese School of Painting

|

|

|

|

|

|

Siena, Palazzo Sansedoni |

|

Siena, Piazza del Campo |

|

Siena, Palio |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Duccio di Buoninsegna, c. 1255 - 1318, The Nativity with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, Washington National Gallery of Art

Duccio di Buoninsegna, c. 1255 - 1318, The Nativity with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, Washington National Gallery of Art