|

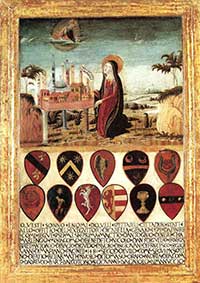

Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome and Mary Magdalene (detail), ca. 1490, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Neroccio di Bartolomeo de' Landi |

| Neroccio di Bartolomeo de' Landi (1447–1500) was an Italian painter and sculptor of the early-Renaissance or Quattrocento period in Siena. By the mid 15th century, the glory days of Medieval Siena were long over. While its art from that period has been widely admired, the later painting of Renaissance period Siena has been largely ignored outside Italy. This is in part because Siena was conquered by neighbouring Florence in the mid 16th century, with the art history of the region written by the victors and the achievements of Sienese artists overshadowed by its more powerful rival. Neroccio di Landi was a student of Vecchietta, and then he shared a workshop with Francesco di Giorgio from 1468. He painted Scenes from the life of St Benedict, now in the Uffizi, probably in collaboration with di Giorgio, and a Madonna and Child between Saint Jerome and Saint Bernard, which is in the Pinacoteca of Siena. In 1472 he painted an Assumption for the abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, and in 1475 he created a statue of Saint Catherine of Siena for the Sienese church dedicated to her. He separated from di Giorgio in 1475. In 1483, he designed the Hellespontine Sybil for the mosaic pavement of the Cathedral of Siena, and the tomb for the Bishop Tommaso Piccolomini del Testa. Neroccio de' Landi, stemming from a distinguished patrician family, seems to have wanted throughout his life to express the nobility of the human face and the elegance of gestures and attitudes in his paintings. He did not make use of many innovations of the first half of the 15th century, and in fact one has the impression as if Neroccio, forgetting about his direct artistic antecedents, had intended to reach back to traditions of the previous century. And yet in fact he knew and employed the devices of perspective and used light and shadow in the modelling of his figures, but he was less interested in these. Neroccio had no wish to deny the two-dimensisonal quality of the surface he painted, and the application of foreshortening and the adding of depth to his composition concerned him only as long and inasmuch as they contributed to the harmonious effect of the composition as a whole. In the light that brushed the faces and hands he did not look for a method to achieve plastic unity and compactness, but rather for a means to expose as much of the beauties of detail as possible and to make the pictorial surface as rich as possible. |

| Sienese artists of the mid 15th century harked back to the glory days of the republic, and sidestepped the realism and naturalistic style of art developing in Florence in favour of strong elegant lines, generous use of gilding and disparities of scale, which served to venerate and uplift those that the city held dear. First and foremost among these was the Virgin Mary, whom the city was dedicated to. She was widely believed to have interceded on the city’s behalf on many occasions, and paintings show her joining the Pope in blessing the city, or protecting it from earthquakes, and her sailors from storms. Along with the Virgin, Siena was devoted to its native saints, particularly Saint Bernadino, a charismatic Franciscan preacher who died in 1444 and canonised just six years later, and Saint Catherine, a much loved Dominican mystic who died in 1380. |

These patrons feature in many paintings from the period, as do other aspects of the city’s strong sense of civic pride – images of the city and its walls and characteristic black and white striped cathedral. This civic pride and wish to be different, in an environment where the territorial ambitions of Florence and other more powerful Italian states loomed ever present, were to shape Siena’s artistic style. The city’s art did not exist in a vacuum, however, and while there was a tradition of copying from art of the city’s golden age before the Black Death of 1348, from artists like Simone Martini, the influence of visits to Siena by artists like Donatello cannot be underestimated. [1] A sculptor as well as a painter, Neroccio de' Landi was one of the most accomplished artists of late fifteenth-century Siena. His painted productions centered on devotional images of the Madonna and Child; this fine example dates from about 1490. The format—with two accompanying saints set behind the Virgin — is conventional, but Neroccio's lyrical, relieflike treatment of the figures and his emphasis on surface refinement are peculiar to him. The exceptionally beautiful frame is not original to the picture but was designed by the great architectural engineer-sculptor-painter Francesco di Giorgio, with whom Neroccio shared a workshop between 1468 and 1475. Neroccio's style remains almost unchanged in his several compositions presenting the Madonna with Child and Saints. The drawing is always perceptibly subtle and light, the colours do not glow with varnish, but enchant with their unlacquered, milky opaque effect. |

Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome and Mary Magdalene, ca. 1490, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

| Portrait of a Lady |

||

Around the turn of the 1460s and '70s, Neroccio and Francesco di Giorgio created together a new, blonde and ethereal female ideal in Sienese painting, of which this Madonna is a beautiful example.

'This is often described as one of the earliest portraits from Renaissance Siena. While humanism and a focus on man and individual accomplishment had helped create a market for portraiture in Florence in the mid 1400s, in Siena it remained rare. There was little demand for private secular art of any kind until the last quarter of the century, when humanism finally asserted itself following the election of Pope Pius II, the former Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini. A member of a prominent Sienese family and noted humanist, he was the first pope to write a true autobiography. The young woman on this panel has a dreamy and idealized beauty, accented by masses of blond hair. (Saint Bernardino preached against women who bleached their hair in the sun and sat in public squares to dry it.) Her three-quarter pose is unusual; most female portraits in Italy at this date were in profile. A slender and long-necked Virgin holds before her the Child, who looks up at his mother while blessing and supporting himself on the armrest of the throne. The sweeping outline of Mary's gold-edged cloak, sharply delineated against the gold ground, still follows the Ducciesque tradition, but signs of receptivity to the new style can be discerned in every detail of the picture. The vigorous figure of the Child was inspired by the reliefs of Donatello, who spent the last years of his life in Siena. Many portraits were commissioned to commemorate a marriage or betrothal. This woman's loose hairstyle suggests that she is not yet married. She may have been a member of the Bandini family, whose crest of sphere- biting eagles appears around the frame, which is probably original. The flames that alternate with the Bandini crest may be a reference to her future husband, or they may hint that her given name was Fiammetta (related to the word for "blaze").'[2] Regarding the composition, the starting point for Neroccio's work was the Madonna type created by Sano di Pietro at the middle of the century. |

|

|

|

Claudia Quinta

|

||

| Claudia Quinta embodied the greatest virtues of Roman womanhood—chastity, piety, and fortitude. It had been prophesied that Roman victory in the Second Punic War depended on bringing Cybele, the Anatolian Great Mother goddess, to Rome. But when a ship with her image arrived at the mouth of the Tiber River, it became mired in mud. Strong men were unable to free it. Claudia was a virtuous young matron, falsely accused of impropriety, who had prayed to Cybele for a sign of her innocence. At the goddess's direction she slipped a slender cord over the ship's bow and easily pulled the vessel free. This painting was part of a set of at least seven works representing paragons of virtue. Such cycles devoted to famous men and women of the past had been popular since the Middle Ages and seemed to enjoy particular favor in Siena. The men and women in this set, taken from ancient literature and the Bible, were renowned for chastity, fortitude, or self-restraint. In civic buildings such cycles usually focused on men of political courage, but because this group contains so many women and concentrates on more "domestic" virtues, it probably decorated a private house.[2] |

||

|

||

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia offers the most exclusive privacy to enjoy a breathtaking view and have a comfortable, regenerating holiday.

|

||||

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Siena, Piazza del Campo |

Orbetello | ||

Bagni San Filippo |

Rocca d'Orcia |

Pitigliano |

||

|

||||

Pieve di Santa Maria dello Spino |

Cipress road near Montichiello |

|||

| This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia articles Neroccio di Bartolomeo de' Landi and Neroccio di Bartolomeo de' Landi published under the GNU Free Documentation License.Wikimedia Commons contiene immagini o altri file su Neroccio di Bartolomeo de' Landi |

||||