|

|

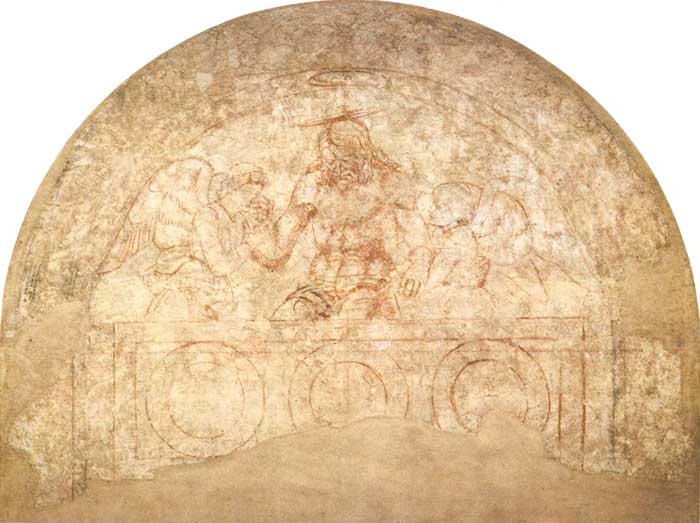

Andrea del Castagno, Stories of Christ's Passion and Last Supper, 1447, fresco, Sant'Apollonia, Florence |

|

Andrea del Castagno |

Andrea del Castagno (originally Andrea di Bartolodi Bargilla), one of the most influential 15th-century Italian Renaissance painters, best known for the emotional power and naturalistic treatment of figures in his work. In 1456 Andrea painted the fresco in Santa Maria del Fiore of the equestrian monument to Niccolò da Tolentino, and in 1457 the Last Supper (lost in 2002) in the refectory of Santa Maria Nuova. Andrea's very intense activity was interrupted by his sudden death, probably from the plague, in 1457. |

|

Cenacolo of Sant’Apollonia with the Famous Men and Women by Andrea del Castagno, photograph from the beginning of the nineteenth century |

|

||

| In the cartoon for the Deposition on one of the stained-glass windows in the dome of Florence Cathedral, Andrea appears to be expressing an emotional intimacy and a formal harmony that are the result of the changing cultural reality: for the Florentine art scene in those years was dominated not only by painters such as Paolo Uccello, Filippo Lippi and Angelico, but also by Domenico Veneziano. The influence of Domenico Veneziano's painting becomes even stronger in the decoration of the refectory of Sant'Apollonia which Andrea painted between June and October 1447. |

||

|

||

|

||

Andrea del Castagno, Stories of Christ's Passion, 1447, fresco, Sant'Apollonia, Florence |

||

| The three scenes from the Passion (the Resurrection, Crucifixion and Entombment) are connected to each other by a group of flying angels all converging towards the figure of Christ in the centre, and by a common landscape background, which has been correctly judged "the most powerful interpretation, of the Tuscan landscape in the entire history of painting" (Berti).

The scene that has been most highly praised, and which is probably the best preserved, is the Resurrection, originally the first to the left. The splendid synopia which was discovered when the fresco was detached from the wall is today on exhibit alongside the fresco itself. |

||

|

||

|

||

Andrea del Castagno, Stories of Christs Passion (synopia), 1447, fresco in Sant'Apollonia, Florence |

||

| 'To create a fresco, the painter began by coating the wall with a layer of plaster, which was made by mixing water with slaked lime, and large-grained river sand. This first layer, about one centimeter thick, is called the arriccio (rendering). The roughness of this surface promotes the adhesion of the second layer of plaster. The artist drew the preparatory drawing directly on this first layer. With a piece of charcoal - easily erasable - he first penciled in the design. Once satisfied with this drawing, he used earth-ochre to trace a second set of lines alongside the charcoal lines. A bunch of feathers was then used to brush away the charcoal lines, and a red earth pigment was used to draw over their faded yellow remnants and to flesh out the details of the representation (folds of drapery, faces, chiaroscuro, etc.). This technique, first introduced in the thirteenth century, was used during most of the fourteenth century for large preparatory drawings. Today sinopia painting is named after the reddish pigment (originally from the city of Sinope) used to execute the technique. Once the sinopia painting was finished, the actual painting could begin. At this point a new layer of plaster, the ‘intonachino' (thin plaster layer) was spread over one area of the arriccio (rendering) to prepare a perfectly smooth surface to receive the coloring. Intonachino (thin plaster layer) is a thin, transparent layer composed of one part slaked lime and two parts finely-ground sand. It was only applied to the surface area the artist expected to be able to color during one day's work, because the surface must be humid during the coloring phase. Then the painter used a brush to trace over the sinopia painting outline, which remained visible through the thin layer of intonachino (thin plaster layer). At last, he began painting with grounded pigments mixed in water.' [2] |

||

| |

||

|

||

|

||

Andrea del Castagno, Resurrection (detail), 1447, fresco, Sant'Apollonia, Florence |

||

| The scene that has been most highly praised, and which is probably the best preserved, is the Resurrection, originally the first to the left. Here, Christ rises up with the monumentality and the solidity of a statue, only slightly mellowed by his melancholy expression and the pale, soft daylight surrounding him. Below him, a group of soldiers lie sound asleep; only one of them has just woken up and observes the incredible event with his mouth open. His features are almost deformed by a blackish shading which makes the modelling hard and sharpedged.

|

|

|

| The obvious analogies between this fresco and the same subject painted several years later by Piero della Francesca in Borgo San Sepolcro has been the object of many critical studies. The simplicity and the perfect perspective composition of the fresco in Sant'Apollonia is considered by some scholars an anticipation of the art of Piero, whereas others think that it is rather a reflection of it. |  |

|

|

||

|

||

Andrea del Castagno, Last Supper (detail), 1447, fresco, Sant'Apollonia, Florence

|

||

| One of Andrea del Castagno's most famous works is the Last Supper he painted below the stories from Christ's Passion. Until quite recently the Last Supper appeared to be painted in much darker colours than the scenes directly above it; the fact had given rise to many animated debates between scholars concerning the dating of the fresco. But after the latest cleaning (1977-79) the colour and tonal contrast between the two levels has disappeared, and the colours of the Last Supper have been restored to their original beauty. The influence of Domenico Veneziano's painting is strong in the decoration of the refectory of Sant'Apollonia which Andrea painted between June and October 1447. He solved the problem posed by the height of the refectory walls in Sant'Apollonia by using the old method of arranging the scenes in two rows, one above the other, but he gave them a visual unity: the Stories of Christ's Passion frescoed on the upper level are in fact conceived as taking place in a space behind the room where the Last Supper on the lower level is happening. The three scenes from the Passion (the Resurrection, Crucifixion and Entombment) are connected to each other by a group of flying angels all converging towards the figure of Christ in the centre, and by a common landscape background, which has been correctly judged "the most powerful interpretation, of the Tuscan landscape in the entire history of painting" (Berti). All scholars agree in praising the sobre architectural structure of the room where the scene of the Last Supper is taking place: a room in the austere style of Alberti, with the lavish coloured marble panels functioning as a backdrop to the heavy and solemn scene of the banquet. Notice also the beauty of some of the minor details, such as the gold highlights in some of the characters' hair or the haloes depicted in perfect perspective. The other extraordinary element of this fresco is the remarkable balance of gestures and expressions, particularly in the group of figures in the centre of the composition, where the innocent sleep of St John to the left of Jesus is contrasted to the tense, rigid figure of Judas sitting opposite. The Last Supper displays del Castagno's talents at his best. The arrangement of balanced figures in an architectural setting is particularly noted. For instance, Saint John's posture of innocent slumber neatly contrasts Jude the Betrayer's tense, upright pose, and the hand positions of the final pair of apostles on either end of the fresco mirror each other with accomplished realism. The colors of the apostles' robes and their postures contribute to the balance of the piece. The detail and naturalism of this fresco portray the ways in which del Castagno departed from earlier artistic styles. The highly detailed marble walls hearken back to Roman "First Style" wall paintings, and that the pillars and statues recall Classical sculpture and preface trompe l'oeil painting. Furthermore, the color highlights in the hair of the figures, flowing robes, and a credible perspective in the halos foreshadow advancements to come. Art in Tuscany | Andrea del Castagno, Last Supper, 1447

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

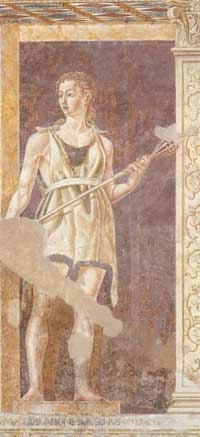

Castagno's work shows his interest in scientific perspective. Not only was he influenced by Masaccio but also by Domenico Veneziano in his use of light colors. He was widely acclaimed, however, for his series of Famous Men and Women produced for the Villa Carducci Pandalfini at Legnaia. The Florentine condottiere Pippo Spano was portrayed by Andrea del Castagno in 1450 as an idealized heroic military commander with his relaxed pose, at ease with feet placed wide apart. In this over-life-size series, Castagno executed figures with the illusion of body movement and expressive facial rendering. He heightened the naturalism by presenting the figures as standing in illusionistic architectural niches. Castagno's emotional portrayal of the young David painted on a shield is similarly realistic and expressive, owing thanks to the influence of Donatello.

|

Eve, 1450 circa, Andrea del Castagno, Soffiano (Firenze), Villa Carducci, Fresco. |

|

| David with the Head of Goliath is unique in Renaissance art. It is the only example of a painted shield that can be attributed to a great master, and it is decorated with a narrative scene instead of the typical coat of arms. Rather than for protection in battle, it was intended for display in ceremonial parades. Images of young David, who overcame seemingly insurmountable odds to kill the giant, were popular in fifteenth-century Florence, the smallest major power in Italy. The city saw itself threatened by such Goliaths as the pope, the duke of Milan, the king of Naples, and the doge of Venice. David's image is especially appropriate decoration for a shield since, throughout the Psalms, David's poetry echoes the notion of God as his shield: "His truth shall be thy shield and buckler" (Ps. 91.4). The unusual shape of this work is explained by its original use as a parade shield. Its painted scene is exceedingly rare — most parade shields were decorated with simple coats of arms. It may have been carried in civic or religious processions or have been made as a sign of authority for a citizen-governor. Like many early Renaissance artists, Castagno has presented the action and its outcome simultaneously: David is depicted preparing to attack Goliath, having already chosen a smooth stone from the riverbank for his sling. The conclusion appears at the bottom of the shield; the terrible giant's severed head, with the stone embedded in its forehead, lies at David's feet as a warning to any potential enemies of Florence For this interpretation of the Old Testament hero, Castagno chose a young athlete, whose pose shows the painter's awareness of classical prototypes. Castagno demonstrated his knowledge of the new science of anatomy by modeling the figure in light and shadow, articulating the muscles and veins of the arms and legs, and giving powerful activity to David's running pose and windblown garments. |

||

| Probably in 1453, Andrea moved to the church of Santissima Annunziata, where he painted two frescoes (St Julian and the Redeemer; The Holy Trinity, St Jerome and Two Saints) that are typical of his late style. No longer interested in the heroic and monumental characteristics illustrated in the Legnaia cycle, Andrea here imbues his figures with the crude truth that he had gradually mastered over a lifetime of hard work. A deeply realistic mood dominates the figure of St Jerome in the fresco in the Corboli Chapel in the Santissima Annunziata. The saint is portrayed as a fully convinced Renaissance ascetic, possessing both humanity and mysticism. In this painting we are immediately struck by a few details that are so realistic they are almost too crude, like the old saint's body with blood gushing out of the many wounds. Above, the Holy Trinity "with a Crucifix in foreshortening; it is so well executed that Andrea deserves great praise for it, for he painted foreshortenings in a much better and more modern manner than any artist had done before him" (Vasari). The St Julian in the Cagliani family chapel in Santissima Annunziata is damaged in its lower section. The figure of the saint is no longer the sophisticated gentleman we saw in the Berlin Madonna: he is simply a young man who is sincerely contrite for the harm he has caused. Above his hair, rendered with golden highlights, the metallic halo realistically reflects the saint's head. Above Julian, partly concealed by pinkish clouds, Christ imparts his blessing. On either side of the saint, in the midst of a lovely Tuscan landscape, Andrea has illustrated some episodes from his life. Also to those years is attributed the Crucifixion for St. Apollonia. In 1456 he executed in the Cathedral the famous fresco of the Equestrian Statue of Niccolò da Tolentino, paralleling the similar painting by Paolo Uccello portraying John Hawkwood. Giorgio Vasari, an artist and biographer of the Italian Renaissance, alleged that Castagno murdered Domenico Veneziano,[5] although this seems rather unlikely - given that Veneziano died in 1461, four years after Castagno died of the plague. |

||

| Little is known about his formation, though it has been hypothised that he apprenticed under Fra Filippo Lippi and Paolo Uccello. In 1440-1441 he executed the fresco of Crucifixion and Saints in the Ospedale di Santa Maria Nuova, whose perspective-oriented construction and figures shows the influence of Masaccio. In 1442 he was in Venice where he executed frescoes in the San Tarasio Chapel of the church of San Zaccaria. In 1445 he became member of the Guild of the Medicians. From the same year is the fresco of Madonna with Child and Santi in the Contini Bonacossi Collection (Uffizi). I Capolavori dell'Arte in Toscana | Andrea del Castagno | Madonna di casa Pazzi

|

|

|

Il Ciclo degli uomini e donne illustri | Famous Persons

|

||

|

||

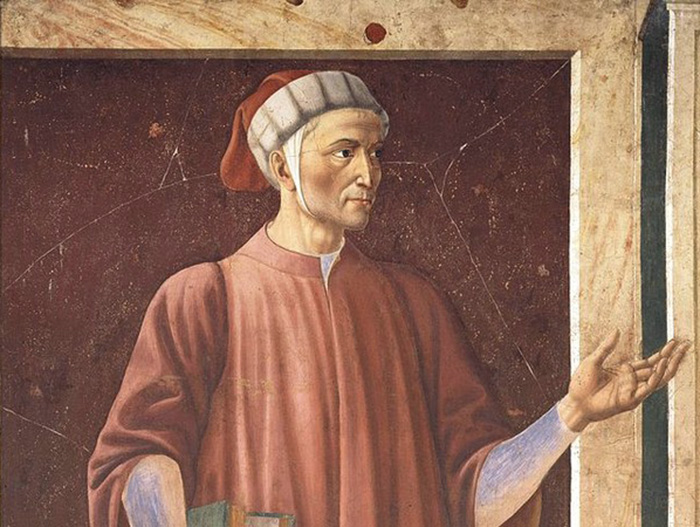

Andrea del Castagno, Dante Alighieri |

||

Art in Tuscany | Il Ciclo degli uomini e donne illustri | Famous Persons

|

||||

| [1] Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, newly translated by Gaston du C. de Vere, vol. 3, 10 vols. (New York: AMS Press, 1976 [reprint of the 1912 ed., London: Philip Lee Warner, Publisher to the Medici Society, Limited]), 97-98. This story appears in both the 1550 and 1568 editions of Vasari’s Lives. For the first edition, see Vasari, Le vite de’ pił eccelenti pittori, scultori ed architettori scritte da Giorgio Vasari, pittore aretino con nuove annotazione e commenti di Gaetano Milanesi, vol. 2, 9 vols. (Firenze: G.C. Sansoni, Editore, 1906), 667-689. It is clear that Vasari adapted his story from those of Antonio Billi and and the Anonimo Gaddiano. The story of Castagno as a young boy drawing in the countryside can be seen as a parallel to Giotto. Vasari used the same topos in his account of Giotto’s discovery, possibly connecting the two artists’ interest in nature and depicting true life. [2] Serena Nocentini | The technique of fresco painting | www.brunelleschi.imss.fi.it [3] In 1998 the Uffizi Gallery has acquired the Contini Bonacossi collection, with temporary entrance from Via Lambertesca (Back to the Uffizi). The collection comprises thirty-five paintings, twelve sculptures, eleven large coats of arms by Della Robbia, in addition to a remarkable group of ancient furniture pieces and majolicas, which were originally part of perhaps the most prestigious collection ever gathered, belonging to Alessandro Contini Bonacossi. The most important pieces are now property of the State, after long and complex hereditary negotiations with the heirs. Its acquisition significantly enriches the patrimony of the Uffizi. Among its pieces we find works attributed to Cimabue and Duccio, in addition to large wooden panels by Sassetta and Giovanni del Biondo, a fresco by Andrea del Castagno and a superb group of paintings of Venetian artists (Veronese, Giambellino, Tintoretto, Cima da Conegliano). One of the most precious pieces is the San Lorenzo, an early work by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

|

Andrea del Castagno, Dante Alighieri, from the Cycle of Famous Men and Women, c. 1450. Detached fresco. 247 x 153 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze. The picture shows one of the three Tuscan poets represented in the cycle. |

|||

| This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Andrea del Castagno", published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||

Art in Tuscany | Italian Renaissance painting Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects | Andrea del Castagno Giorgio Vasari | Le vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri | Andrea da 'l Castagno di Mugello Joost Keizer, History, origins, recovery : Michelangelo and the politics of art. |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, mystic holiday home in the heart of the Tuscan Maremma

|

The appealing clearness of Podere SantaPia in a mild winter landscape

|

Colline sotto Podere Santa Pia, paesaggio di Giuseppe Ungaretti |

||

Podere Santa Pia, Castiglioncello Bandini, Cinigiano, Toscana

|

||||

A beautiful early evening by the pool, in the resplendent Tuscan sun, time takes on a languid quality |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

| Podere Santa Pia offers d stunning views to to the Tyrrhenian coast and Monte Christo and even Corsica | ||||

|

||||

|

|

|||

Lucca, Anfiteatro |

Florence, Orsanmichele

|

Florence, Duomo Santa Maria del Fiore |

||