|

||

Sandro Botticelli, The Trials and Calling of Moses, 1481-82, fresco, 348,5 x 558 cm, Cappella Sistina, Vatican

|

| Sandro Botticelli |

Sandro Botticelli, (1445-1510) was an Italian painter of the Florentine school during the Early Renaissance. |

||

The masterworks Primavera (c. 1482) and The Birth of Venus (c. 1485) were both seen by Vasari at the villa of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici at Castello in the mid-16th century, and until recently, it was assumed that both works were painted specifically for the villa. Recent scholarship suggests otherwise: the Primavera was painted for Lorenzo's townhouse in Florence, and The Birth of Venus was commissioned by someone else for a different site. By 1499, both had been installed at Castello. Influence of Savonarola

|

||

In later life, Botticelli was one of Savonarola's followers, though the full extent of Savonarola's influence is uncertain. The story that he burnt his own paintings on pagan themes in the notorious "Bonfire of the Vanities" is not told by Vasari, who nevertheless asserts that of the sect of Savonarola "he was so ardent a partisan that he was thereby induced to desert his painting, and, having no income to live on, fell into very great distress. For this reason, persisting in his attachement to that party, and becoming a Piagnone[7] he abandoned his work.". Botticelli biographer Ernst Steinman searched for the artist's psychological development through his Madonnas. In the "deepening of insight and expression in the rendering of Mary's physiognomy", Steinman discerns proof of Savonarola's influence over Botticelli. This means that the biographer needed to alter the dates of a number of Madonnas to substantiate his theory; specifically, they are dated ten years later than before. Steinman disagrees with Vasari's assertion that Botticelli produced nothing after coming under the influence of Girolamo Savonarola. Steinman believes the spiritual and emotional Virgins rendered by Sandro follow directly from the teachings of the Dominican monk. Private life Botticelli never wed, and expressed a strong aversion to the idea of marriage, a prospect he claimed gave him nightmares. |

||

|

||

|

||

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (detail), c. 1486, tempera on canvas, Uffizi, Florence |

||

A close-up of the Venus figure in Botticelli's legendary The Birth of Venus. Botticelli's model for his most famous art work was the beautiful Simonetta Vespucci. Once nominated "The Queen of Beauty" at a Florentine jousting tournament, it was Simonetta's face that Botticelli painted on an art banner. The art banner was carried into battle by the tournament winner, Giuliano de' Medici, a man soon to become her lover. Inscribed beneath her image, Botticelli described her as "the unparalleled one."

|

|

|

Primavera

|

||

| Botticelli painted Primavera for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici (1463–1503), one of Lorenzo the Magnificent’s cousins. Venus stands just to the right of center with her son Cupid hovering above her head. Botticelli drew attention to Venus by opening the landscape behind her to reveal a portion of sky that forms a kind of halo around the goddess of love’s head. To her right, seemingly the target of Cupid’s arrow, are the dancing Three Graces, based closely on ancient prototypes but clothed,albeit in thin, transparent garments. At the right, the blue ice-cold Zephyrus, the west wind, is about to carry off and marry the nymph Chloris, whom he transforms into Flora, goddess of spring, appropriately shown wearing a rich floral gown. At the far left, the enigmatic figure of Mercury turns away from all the others and reaches up with his distinctive staff, the caduceus, perhaps to dispel storm clouds. The sensuality of the representation, the appearance of Venus in springtime, and the abduction and marriage of Chloris all suggest the occasion for the painting was young Lorenzo’s wedding in May 1482. But the painting also sums up the Neo-Platonists’ view that earthly love is compatible with Christian theology. In their reinterpretation of classical mythology, Venus as the source of love provokes desire through Cupid. Desire can lead either to lust and violence (Zephyr) or, through reason and faith (Mercury), to the love of God. Primavera, read from right to left, served to urge the newlyweds to seek God through love.[Source: The Renaissance in Quattrocento Italy. Chapter 21, p.559] | ||

|

||

Sandro Botticelli, Adoration of the Magi, c. 1475-1476, tempera on panel, Uffizi, Florence |

||

At the height of his fame, the Florentine painter and draughtsman Sandro Botticelli was one of the most esteemed artists in Italy.

|

Sandro Botticelli, 1446 - 1510, The Adoration of the Magi, c. 1478/1482, tempera and oil on panel, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington |

|

Frescoes in the Sistine Chapel

|

||

Botticelli painted three major frescos in the Sistine Chapel: The Temptation of Moses and The Punishment of Korah were on the South wall and the Temptation of Christ on the North wall. He also painted at least seven of the papal portraits that were in the window zone of the chapel. As far as the content of the pictures, Botticelli was not one of the decision makers. He was told what subjects to portray and then to portray their stories. Just being able to be part of the project in the Sistine Chapel was a great honor for any artist during that time period. |

||

The Temptation of Christ

|

||

In a series of sequential scenes, we can see the moments of the temptation of Christ, amongst which, the culminating moment: Atop the Temple, Satan shows Christ the world and tells him that "All this is yours". Along the way, other moments of this temptation of Christ are presented in groups which end when Satan, finally defeated, opts to throw himself from the top of the rocks rather than to continue to witness Christ's ardor. Botticelli recounts the Temptations of Christ in a somewhat medieval manner, juxtaposing several stories in a single scene, at the risk of making it denser, which it does. One detail in the Adoration of the Eucharist, the big central scene is admirable - the bearer of offerings, who recalls one of the Graces at the Lemmi Villa and who is a forebear of the Graces of Spring. |

||

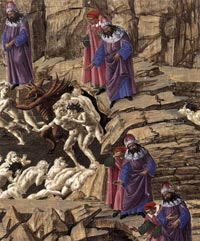

The Trials of Moses

|

||

This fresco is just as ponderous and complex. The burning bush, representing Moses' encounter with God, is there, along with Jethro's daughters, the preparations for the ascent of Mount Sinai with Moses baring his feet, Moses striking an Egyptian, as he does not yet know that he is not Egyptian. All these episodes of Moses' history converge on Jethro's well, the central confluence, with the two figures of Jethro's daughters , all in white; once again, we find this lily-white translucency, in which Botticelli's continuing orientation toward an infinitely elegant and delicate art can be seen. |

||

The Punishment of Korah, Dathan and Abiram

|

||

This is certainly the best of the frescoes. Aaron, the priest, had been challenged by three rebels who no longer respected his authority and proposed that a double sacrifice be performed: the rebels would make their offering and Aaron his, and they would then see which was accepted by God. Of course, the smoke from Aaron's pyre rose straight to heaven, while the rebels' sacrifice flame set them on fire. A superb story, very vividly told, this is one of the first times that Botticelli set out to tell a perfectly dynamic story which even mimics persons. The whole painting is brought together by a superb landscape, the most successful of all; this landscape is further unified by a nearly exact copy of the Arch of Constantine which Botticelli introduced into this scene, a nearly completely archeological vision of this Roman monument against a background of a lake and mountains, which gives the whole painting exceptional vigor and power. |

||

Late paintings (from 1490)

|

||

| The political and religious crisis of the 1490s clearly left its mark on Botticelli's late work. He created fewer monumental works and devoted himself principally to producing devotional pictures and small altars. His themes was now almost exclusively religious ones. In his style there was a decisive change to a hitherto unknown degree of soberness and strictness. In his compositions, he increasingly dispensed with lively decorations, concentrating instead on expressive structuring of the figures. It would be oversimplifying to ascribe this evident change in Botticelli's later works exclusively to the influence of Savonarola, as Vasari does. If he is to be believed, Botticelli was a keen follower of Savonarola, and neglected his work to such an extent that he became impoverished. But quite the opposite must have been the case, he was reasonably well off, and he continued to work until after 1500, as is proven by existing works and documents. However, the artist did not remain unaffected by the events of his time. The change in Botticelli's style appears to be an indicator of the spirit of the time shortly before the end of the century, shaped as it was by political unrest and a belief that the last days were at hand.[3] | ||

| Botticelli's theme for the Calumny of Apelles was drawn from a famous painting by the Greek artist Apelles, described in classical sources. It was a well-known work in the 15th century. Lucian's description of this lost work by the classical artist had been widely translated. Apelles produced his painting because he was unjustly slandered by a jealous artistic rival, Antiphilos, who accused him in front of the gullible king of Egypt, Ptolemy, of being an accomplice in a conspiracy. After Apelles had been proven to be innocent, he dealt with his rage and desire for revenge by painting this picture. In his painting, Botticelli kept the scenic structure of the composition of the figures to Lucian's description, and created a lavishly decorated architectural backdrop for them. An innocent man is dragged before the kings throne by the personifications of Calumny, Malice, Fraud and Envy. They are followed to one side by Remorse as an old woman, turning to face the naked Truth, who is pointing towards heaven. The nakedness of Truth places her in a relationship with the innocent youth, whose folded hands are also an appeal to a higher power. |

||

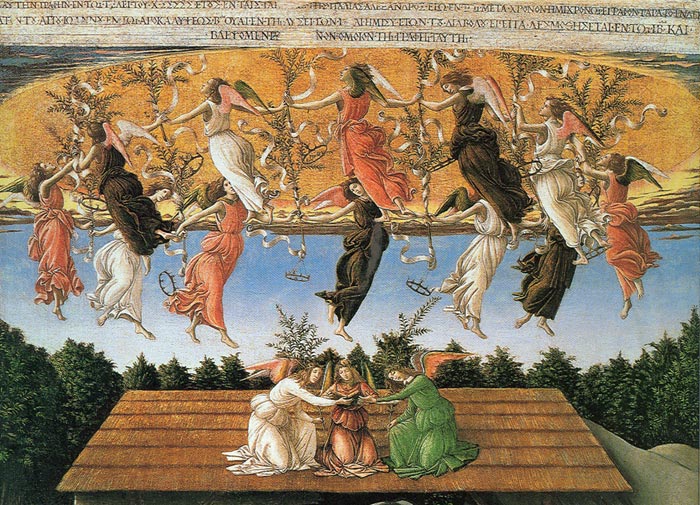

Mystic Nativity

|

||

|

||

Sandro Botticelli, Mystical Nativity(detail), about 1501, Tempera on canvas, 108.6 x 74.9 cm, London, National Gallery |

||

The 'Mystic Nativity' shows angels and men celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ. The Virgin Mary kneels in adoration before her infant son, watched by the ox and the ass at the manger. Mary's husband, Joseph, sleeps nearby. Shepherds and wise men have come to visit the new-born king. Angels in the heavens dance and sing hymns of praise. On earth they proclaim peace, joyfully embracing virtuous men while seven demons flee defeated to the underworld. |

||

| Botticelli often concerned himself during his lifetime with illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy. He executed the drawings from the cycle illustrated here over a relatively long period of time, from about 1480 to 1500. The identification of these illustrations with the Dante cycle which Botticelli is known to have done for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco, his great patron from the Medici family, seems not improbable. For some reason unknown to us, the drawings were never completed. Only four of the surviving 93 sheets - nine having been lost in the course of time - are coloured, although this was presumably the original intention for all of them. The drawings are now in the collections of the Staatliche Museen in Berlin and the Vatican Library. Dante wrote over 14.000 verses describing his visionary journey through the kingdoms of Hell (Inferno), Purgatory (Purgatorio) and Paradise (Paradiso). The epic is divided into 100 cantos: 34 for Hell and 33 each for Purgatory and Paradise. Dante is at first guided on his journey by the classical poet Virgil, but in Paradise he is led by his muse, Beatrice. During his journey Dante meets a large number of nameless people, and also famous personalities from the past and his own age. Every one of them has received the place he deserves as a result of the offences or merits of his life. Art in Tuscany | Sandro Botticelli | Illustrations for Dante's Divinia Comedia |

||

|

||

|

||

Sandro Botticelli and Bartolomeo di Giovanni, La historia de Nastagio degli Onesti (third episode, detail), 1483, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

||

| In the 1480s Botticelli gained commissions from the families in high society. Increasingly they chose classical themes for the luxurious decoration of their town houses, but they also included some from contemporary literature. In order to be able to carry out his multiple commissions, Botticelli had to work together with other painters as well as members of his own workshop. The four panels conveying the Story of Nastagio degl Onesti, the eighth novel of the fifth day of Boccaccio's Decameron, were produced with the aid of Bartolomeo di Giovanni. The Story of Nastagio degl Onesti is the story of Nastagio, a young man from Ravenna who was rejected by the daughter of Paolo Traversari and abandoned the city to settle on its outskirts. Nastagio degli Onesti, whose beloved initially refused to marry him, finally weds her after all. First of all, however, he must remind her of the eternal agony in hell of another merciless woman, one who had also refused marriage, her rejected lover had to pursue her until he had caught up with her, killed her, torn out her heart and intestines and fed them to his dogs. In the second Panel, Nastagio runs away in fright after witnessing the scene, while the persecution begins again in the background. After his initial sense of repulsion, Nastagio decides to take advantage of the story and invites his beloved to come there for a meal with her family. The third panel shows the guests' reaction to the events, and how Nastagio's beloved uses a maid to indicate that she is willing to marry him. The fourth panel depicts the wedding banquet. The fourth painting naturally represents the woman saying sweetly: "In that case, I'll marry you", and we are present for the marriage of Dona Lucrezia Bini and Ugolino degli Onesti. A considerable contribution to the execution of this panel by Jacopo del Sellaio is assumed. The fourth panel belongs to a private collection, the three others are kept in Madrid, Prado. The paintings were commissioned in 1483 by Antonio Pucci for the marriage of his son, Giannozzo, with Lucrezia Bini. The coats of arms of both families flank those of the Medici on the third panel. Specialists see Botticelli's hand in the overall design and in certain figures. They also detect the participation of his assistants, Bartolomeo di Giovanni and Jacopo del Sellaio. Art in Tuscany | Sandro Botticelli, The Story of Nastagio degl Onesti |

||

Storia di Virginia Romana |

||

|

||

Sandro Botticelli, Storia di Virginia Romana, Bergamo, Accademia Carrara |

||

Though cassoni were made in many countries, the finest come from Italy. Cassone is the Italian term for chest or coffer, usually a bridal or dower chest, highly ornate and given prominence in the home. Chest, usually of wood, intended to contain a bride's dowry or to be given as a wedding present. It was the most elaborately decorated piece of furniture in Renaissance Italy. In the 15th century, wealthy Florentine families employed artists such as Sandro Botticelli and Paolo Uccello to decorate cassoni with paintings. They were often made in pairs, bearing the respective coats of arms of the bride and groom. |

||

| A small round stone in the Franciscan Church of Ognissanti marks the resting-place of Sandro Boticelli. In the centre of the tombstone one can see the Filipepi family coat of arms, surrounded by the inscription in Latin containing the year of the artist's death - 1510. His tombstone can be found in the floor of the Cappella San Pietro d’ Alcantara in the south transept of the Chiesa Ognissanti in Florence. There is Botticelli's fresco of Saint Augustine in his Study (1480) in the same church. |  |

|

[1] Guasparre del Lama was a parvenu from the humblest background with a dubious past - he had been convicted of the embezzlement of public funds in 1447. He had been working since the 1450s as a broker and money-changer, something which brought him considerable wealth. In order that he might also obtain the high social standing which he lacked, he enrolled in the most prestigious brotherhoods and endowed a chapel in Santa Maria Novella, which he decorated with Botticelli's altar-piece. Del Lama's career did not last long, for he soon slipped back into his dishonest business practices. |

||

Hein-Thomas Altcappenberg , Sandro Botticelli: The Drawings for Dante's Divine Comedy, Royal Academy Books, 2000 |

||

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Sunsets in Tuscany |

|||

Siena, Palazzo Publico |

Siena, Duomo |

Val d'Orcia |

||

|

||||

| Bomarzo | Asciano, Crete Senesi |

Sunsets in Tuscany |

||

Podere Santa Pia is located in the heart of the Valle d'Ombrone, and one can easily reach some of the most beautiful attractions of Tuscany, such as Montalcino, Pienza, Montepulciano and San Quirico d'Orcia, famous for their artistic heritage.

|

||||

|

||||

| The surroundings of Podere Santa Pia, cipresses between Montalcino and Pienza |

||||

This page uses material from the Wikipedia article Sandro Botticelli, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

||||

Spring by Botticelli. The central figure is presumed to be a portrait of La Bella Simonetta.

Spring by Botticelli. The central figure is presumed to be a portrait of La Bella Simonetta.