| |

|

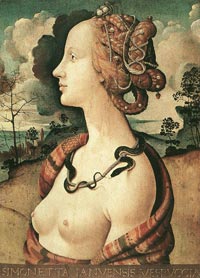

Simonetta Cattaneo de Vespucci, nicknamed la bella Simonetta (ca. 1453 – 26 April 1476) was the Genoese wife of the Italian nobleman Marco Vespucci of Florence. She also is alleged to have been the mistress of Giuliano de' Medici, Lorenzo the Magnificent's younger brother. She was renowned for being the greatest beauty of her age - certainly of the city of Florence. She is depicted in Piero di Cosimo's paintings Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci, in which she is portrayed as Cleopatra with an asp around her neck, and The Death of Procris. Countless poems and canvasses by many other painters were also created in her honor.

Early life and marriage

She was born as Simonetta Cattaneo circa 1453 in Liguria. Her father was a Genoese nobleman named Gaspare Cattaneo Della Volta, and her mother was his wife, Cattocchia Spinola de Candia. Her exact birthplace is uncertain: possibly Genoa, or possibly the villages of Fezzano or Portovenere. The poet Poliziano wrote that her home was "in that stern Ligurian district up above the seacoast, where angry Neptune beats against the rocks ... There, like Venus, she was born among the waves."

At age fifteen or sixteen she married Marco Vespucci, son of Piero, who was a distant cousin of the famous Florentine explorer and cartographer Amerigo Vespucci. They met in April 1469; she was with her parents at the church of San Torpete when she met Marco; the doge Piero il Fregoso and much of the Genoese nobility were present.

Marco had been sent to Genoa by his father, Piero, to study at the Banco di San Giorgio. Marco was accepted by Simonetta's father, and he was very much in love with her, so the marriage was logical. Her parents also knew the marriage would be advantageous because Marco's family was well connected in Florence, especially to the Medici family.

Florence

Simonetta and Marco were married in Florence. Simonetta was instantly popular at the Florentine court. The Medici brothers, Lorenzo and Giuliano took an instant liking towards her. Lorenzo permitted the Vespucci wedding to be held at the palazzo in Via Larga, and held the wedding reception at their lavish Villa di Careggi. Through the Vespucci family Simonetta was discovered by Sandro Botticelli and other prominent painters upon arriving in Florence. Before long every nobleman in the city was besotted with her, even the brothers Lorenzo and Giuliano of the ruling Medici family. Lorenzo was occupied with affairs of state, but his younger brother was free to pursue her.

At La Giostra (a jousting tournament) in 1475, held at the Piazza Santa Croce, Giuliano entered the lists bearing a banner on which was a picture of Simonetta as a helmeted Pallas Athene painted by Botticelli himself, beneath which was the French inscription La Sans Pareille, “The unparalleled one.” From then on Simonetta became known as the most beautiful woman in Florence, and later the most beautiful woman of the Renaissance.

Giuliano won the tournament and the affection of la bella Simonetta, who was nominated “The Queen of Beauty” at that event. It is unknown, however, if they actually became lovers. Death

Simonetta Vespucci died just one year later, on the night of 26–27 April 1476, probably from pulmonary tuberculosis. She was only twenty-two at the time of her death. Her husband remarried soon afterwards. The entire city was reported to mourn at her death and thousands followed her coffin to its burial.

Botticelli finished painting The Birth of Venus in 1485, nine years later. Some have claimed that Venus, in this painting, closely resembles Simonetta. This claim, however, is dismissed as "romantic nonsense" by noted historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto:

"The vulgar assumption, for instance, that she was Botticelli's model for all his famous beauties seems to be based on no better grounds than the feeling that the most beautiful woman of the day ought to have modelled for the most sensitive painter."

Some suggest that Botticelli also had fallen in love with her, a view supported by his request to be buried at her feet in the Church of Ognissanti - the parish church of the Vespucci - in Florence. His wish was in fact carried out when he died some 34 years later, in 1510.[1]

|

| |

|

|

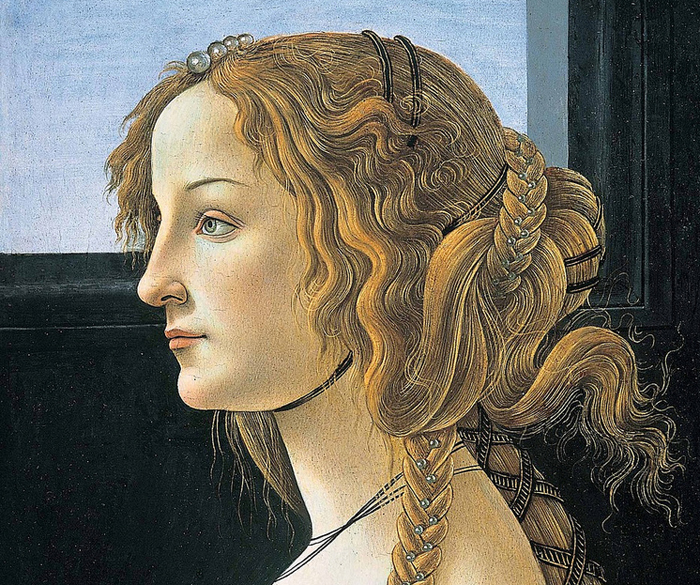

The Portrait of a Young Woman is a painting by the Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli, executed around 1480-1485. It is housed in the Stadelsches Kunstinstitut of Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

The sitter is identified as Simonetta Vespucci on basis of a portrait by Piero di Cosimo. The attribution to Botticelli is debated, some scholars give the painting to Jacopo del Sellaio.

As in Bartolomeo Veneto’s Idealized Portrait of a Courtesan as Flora, it is clear from the sitter’s fantastic outfit that Botticelli’s larger-than-life-size head-and-shoulders portrait of a young lady of about 1480 is not a portrait in the literal sense but an idealized likeness in the mythological costume of a nymph. This is the reason for the thick, magnificent head of hair, richly decked out with strings of pearls, ribbons, and hairpieces and crowned with a feathered agrafe. The young woman shown in profile has the features of Simonetta Vespucci, who died young and was probably the lover of Giuliano de’ Medici. Unlike his brother, Lorenzo il Magnifico, Giuliano fell victim to the Pazzi conspiracy in 1482. The pendant of the sitter’s necklace also points to the Medici’s immediate family. It is patterned after a famous ancient intaglio from the Medici collection.

Being one of the largest in size of 15 th century female portraits, Boticelli’s hand work is easily found in the detail and excellence of the woman in the picture. Simonetta Vespucci, a prominent member of the Medici circle, is wearing a hairstyle that can typically be seen on nymph. The pearls in her hair and braids can also be linked to the nymphs. Her braids, if let loose, would also disrobe her revealing a very sensual overtone to the picture. Botticelli used the same type of braiding overlapping clothing in Venus and Mars. In contrast, just over Simonetta’s right shoulder is a breastplate which is one of the characteristics that is associated with a chaste and idealistic woman.

The medal on the necklace in the portrait is the mirror image of Apollo, Marsyas and Olympos. The cameo may have been just an antique ornament or there could be a much larger theme surrounding Apollo and Marsyas that is not clearly presented.

There is great beauty in the painting ranging from the ornate hair clip to the elaborate hairstyle. The plain background suggests a focus on the subject herself.

Botticelli’s enormous portrait was originally set into the wooden panelling in the stateroom of a Florentine palazzo as part of a larger cycle of paintings, which probably also included a matching portrait of Giuliano de’ Medici.

|

|

Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of a Young Woman, Städel Museum ,Frankfurt Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of a Young Woman, Städel Museum ,Frankfurt

|

| |

|

|

|

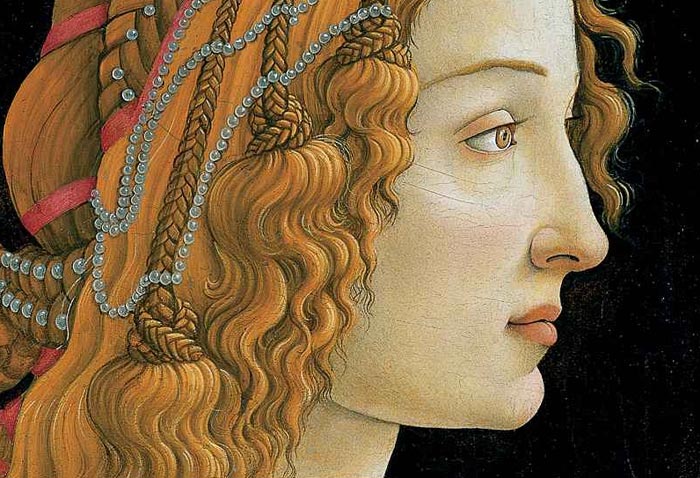

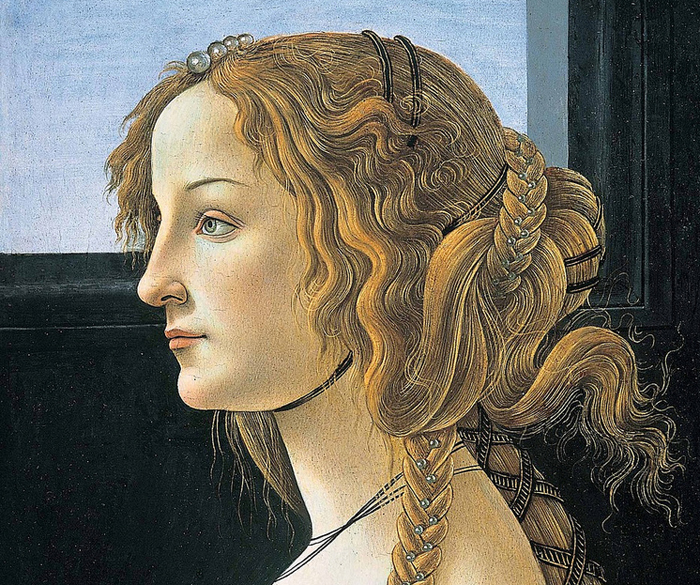

| Sandro Botticelli, Simonetta Vespucci, portrait of a Young Lady, Berlin, Staatliche Museen Nationalgalerie

|

The Portrait of a Young Woman by Sandro Botticelli was executed around 1480-1485. It is housed in the Städel of Frankfurt, Germany. Other Botticelli portraits with the same name are housed in Uffizi, Florence, and the Staatliche Museen in Berlin.[3]

The sitter is identified as Simonetta Vespucci on basis of a portrait by Piero di Cosimo. The attribution to Botticelli is debated, some scholars give the painting to Jacopo del Sellaio.

The subject, likely Simonetta Vespucci, is shown in side profile, wearing "Nero's Seal" around her neck.

|

|

|

| |

|

Sandro Botticelli: Simonetta Vespucci, portrait of a Young Lady, Berlin, Staatliche Museen Nationalgalerie |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Podere Santa Pia is a wonderful place to relax and enjoy the treasures of Tuscany, close to the Tyrrhenian coast but set in an oasis of green and abundant nature. The house is set on the top of a lush hill, in a private yet not isolated spot, with breath-taking views of the sea, until Monte Argentario and the island of Monte Christo.

If you love great wines, great food and great scenery, Santa Pia is the ideal location. There are many wineries in the area, one can enjoy wine tastings of the famous Brunello, Montecucco and Montepulciano wines, and experience the best of Tuscany on day tours to Montalcino, Montepulciano, Scansano and the surreal beauty of the Val D'Orcia, and enjoy wine tastings of the famous Brunello, Montecucco and Montepulciano wines.

Hidden secrets and holiday houses in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia| Artist and writer's residency in spring and autumn

|

|

Podere Santa Pia is an old farm that has been renovated into a perfect holiday house located 350 meters above sea level in a panoramic position. Although this is off the beaten track it is the ideal choice for those seeking a peaceful, uncontaminated environment.

|

[1] Sandro Botticelli was a Florentine painter, born at Florence in 1444 in a house in the Via Nueva, Borg' Ognissanti. This was the home of his father, Mariano di Vanni dei Filipepi, a struggling tanner. Sandro, the youngest child, derived the name Botticelli by which he was commonly known, not, as related by Giorgio Vasari, from a goldsmith to whom he was apprenticed, but from his eldest brother Giovanni, a prosperous broker, who seems to have taken charge of the boy and who for some reason bore the nickname Botticello or Little Barrel. A return made in 1457 by his father describes Sandro as aged thirteen, weak in health, and still at school (if the words "sta al legare" are to be taken as a misspelling of "sta al leggere", otherwise they might perhaps mean that he was apprenticed either to a jeweller or a bookbinder). One of his elder brothers, Antonio, who afterwards became a bookseller, was at this time in business as a goldsmith and gold-leaf beater, and with him Sandro was very probably first put to work.

Having shown an irrepressible bent towards painting, he was apprenticed in 1458-59 to Fra Filippo Lippi, in whose workshop he remained as an assistant apparently until 1467, when the master went to carry out a commission for the decoration with frescoes of the cathedral church of Spoleto. During his apprentice years Sandro was no doubt employed with other pupils upon the great series of frescoes in the choir of the Pieve at Prato upon which his master was for long intermittently engaged. The later among these frescoes in many respects anticipate, by charm of sentiment, animation of movement and rhythmic flutter of draperies, some of the prevailing characteristics of Sandro's own style. One of Sandro's earliest extant pictures, the oblong "Adoration of the Magi" at the National Gallery, London (No. 592, long ascribed in error to Filippino), shows him almost entirely under the influence of his first master. Left in Florence on Fra Filippo's departure to Spoleto, he can be traced gradually developing his individuality under various influences, among which that of the realistic school of the Pollaiuoii is for some time the strongest. From that school he acquired a knowledge of bodily structure and movement, and a searching and expressive precision of linear draughtsmanship, which he could never have learned from his first master. The Pollaiuolo influence dominates, with some slight admixture of that of Andrea del Verrocchio, in the fine figure of Fortitude, now in the Uffizi, which was painted by Botticelli for the Mercanzia about 1470; this is one of a series of the seven Virtues, of which the other six, it seems, were executed by Piero Pollaiuolo from the designs of his brother Antonio. The same influence is again very manifest in the two brilliant little pictures at the Uffizi in which the youthful Botticelli has illustrated the story of Judith and Holofernes; in his injured portrait of a man holding a medal of Cosimo de Medici, No. 1286 at the Uffizi; and in his life-sized "St. Sebastian" at Berlin, which we know to have been painted for the church of Sta. Maria Maggiore in 1473. Tradition and internal evidence seem also to point to Botticeili's having occasionally helped, in his earliest or Pollaiuolo period, to furnish designs to the school of engravings in Florence which had been founded by the goldsmith Maso Finiguerra.

Some authorities hold that he must have attended for a while the much-frequented workshop of Verrocchio. But the "Fortitude" is the only authenticated early picture in which the Verrocchio influence is really much apparent; the various other pictures on which this opinion is founded, chiefly Madonnas dispersed among the museums of Naples, Florence, Paris and elsewhere, have been shown to be in all probability the work not of Sandro himself, but of an anonymous artist, influenced partly by him and partly by Verrocchio, whose individuality it has been endeavored to reconstruct under the provisional name of Amico di Sandro. At the same time we know that the young Botticelli stood in friendly relations with some of the pupils in Verrocchio's workshop, particularly with Leonardo Da Vinci. Among the many "Madonnas" which bear Botticelli's name in galleries public and private, the earliest which carries the unmistakable stamp of his own hand and invention is that which passed from the Chigi collection at Rome to that of Mrs. Gardner at Boston. At the beginning of 1474 he entered into an agreement to work at Pisa, both in the Campo Santo and in the chapel of the Incoronata in the Duomo, but after spending some months in that city abandoned the task, we know not why. Next in the order of his preserved works comes probably the much-injured round of the "Adoration of the Magi" in the National Gallery (No. 1033), long ascribed in error, like the earlier oblong panel of the same subject, to Filippino Lippi. (To about this date is assigned by some the well-known "Assumption of the Virgin surrounded with the heavenly hierarchies", formerly at Hamilton Palace and now in the National Gallery [No. 1126]; but modern criticism has proved that the tradition is mistaken which since Vasari's time has ascribed this picture to Botticelli, and that it is in reality the work of a subordinate painter somewhat similarly named, Francesco Botticini.)

A more mature and more celebrated "Adoration of the Magi" than either of those in the National Gallery is that now in the Uffizi, which Botticelli painted for Giovanni Lami, probably in 1477, and which was originally placed over an altar against the front wall of the church of Sta. Maria Novella to the right inside the main entrance. The scene is here less crowded than in some other of the master's representations of the subject, the conception entirely sane and masculine, with none of those elements of bizarre fantasy and over-strained sentiment to which he was sometimes addicted and which his imitators so much exaggerated; the execution vigorous and masterly. The picture has, moreover, special interest as containing lifelike portraits of some of the chief members of the Medici family. Like other leading artists of his time in Florence, Botticelli had already begun to profit by the patronage of this family. For the house of Lorenzo de Medici in the Via Larga he painted a decorative piece of Pallas with lance and shield (not to be confounded with the banner painted with a similar allegoric device of Pallas by Verrocchio, to be carried by Giuliano de Medici in the famous tournament in 1475 in which he wore the favor of La Bella Simonetta, the wife of his friend Marco Vespucci). This Pallas by Botticelli is now lost, as are several other decorative works in fresco and panel recorded to have been done by him for Lorenzo between 1475 and Lorenzo's death in 1492. But Sandro's more especial patron, for whom were executed several of his most important still extant works, was another Lorenzo, the son of Pierfrancesco de Medici, grandson of a natural brother of Cosimo Pater Patriae, and inheritor of a vast share of the family estates and interests. For the villa of this younger Lorenzo at Castello Botticelli painted about 1477-78 the famous picture of "Primavera" or Spring now in the Academy at Florence. The design, inspired by Politian's poem the "Giostra", with reminiscences of Lucretius and of Horace (perhaps also, as has lately been suggested, of the late Latin "Mythologikon" of Fulgentius) thrown in, is of an enchanting fantasy, and breathes the finest and most essential spirit of the early Renaissance at Florence. Venus fancifully draped, with Cupid hovering above her, stands in a grove of orange and myrtle and welcomes the approach of Spring, who enters heralded by Mercury, with Flora and Zephyrus gently urging her on. In pictures like this and in the later "Birth of Venus", the Florentine genius, brooding with passion on the little that it really yet knew of the antique, and using frankly and freshly the much that it was daily learning of the truths of bodily structure and action, creates a style wholly new, in which something of the strained and pining mysticism of the middle ages is intimately and exquisitely blended with the newly awakened spirit of naturalism and the revived pagan delight in bodily form and movement and richness of linear rhythm. In connection with this and other classic and allegoric pictures by the master, much romantic speculation has been idly spent on the supposition that the chief personages were figured in the likeness of Giuliano de Medici and Simonetta Vespucci. Simonetta in point of fact died in 1476, Giuliano was murdered in 1478; the web of romance which has been spun about their names in later days is quite unsubstantial; and there is no reason whatever why Botticelli should have introduced the likenesses of these two supposed lovers (for it is not even certain that they were lovers at all) in pictures all of which were demonstrably painted after the death of one and most of them after the death of both.

The tragedy of Giuliano's assassination by the Pazzi conspirators in 1478 was a public event which certainly brought employment to Botticelli. After the capture and execution of the criminals he was commissioned to paint their effigies hanging by the neck on the walls of the Palazzo del Podestà, above the entrance of what was formerly the Dogana. In the course of Florentine history public buildings had on several previous occasions received a similar grim decoration: the last had been when Andrea del Castagno painted in 1434 the effigies, hanging by the heels, of the chief citizens outlawed and expelled on the return of Cosimo de Medici. Perhaps from the time of this Pazzi commission may be dated the evidences which are found in some of Botticelli's work of a closer study than heretofore of the virile methods and energetic types of Castagno. His frescoes of the hanged conspirators held their place for sixteen years only, and were destroyed in 1494 in consequence of another revolution in the city's politics. Two years later (1480) he painted in rivalry with Domenico Ghirlandaio a grand figure of St. Augustine on the choir screen of the Ognissanti, now removed to another part of the church. About the same time we find clear evidence of his contributing designs to the workshops of the "fine-manner" engravers in the shape of a beautiful print of the triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne adapted from an antique sarcophagus (the only example known is in the British Museum), as well as in nineteen small cuts executed for the edition of Dante with the commentary of Landino printed at Florence in 1481 by Lorenzo della Magna. This series of prints was discontinued after canto XIX, perhaps because of the material difficulties involved by the use of line engravings for the decoration of a printed page, perhaps because the artist was at this time called away to Rome to undertake the most important commission of his life. Due possibly to the same call is the unfinished condition of a much-damaged, crowded "Adoration of the Magi" by Botticelli preserved in the Uffizi, the design of which seems to have influenced Leonardo da Vinci in his own Adoration (which in like manner remains unfinished) of nearly the same date, also at the Uffizi.

The task with which Botticelli was charged at Rome was to take part with other leading artists of the time (Ghirlandaio, Cosimo Rosselli, Perugino and Pinturicchio) in the decoration of the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican, the ceiling of which was afterwards destined to be the field of Michelangelo's noblest labors. Internal evidence shows that Sandro and his assistants bore a chief share in the series of papal portraits which decorate the niches between the windows. His share in the decoration of the walls with subjects from the Old and the New Testament consists of three frescoes, one illustrating the history of Moses (several episodes of his early life arranged in a single composition); another the destruction of Korah, Dathan and Abiram; a third the temptation of Christ by Satan (in this case the main theme is relegated to the background, while the foreground is filled with an animated scene representing the ritual for the purification of a leper). On these three frescoes Botticelli labored for about a year and a half at the height of his powers, and they may be taken as the central and most important productions of his career, though they are far from being the best-known, and from their situation on the dimmed and stained walls of the chapel are by no means easy of inspection. Skill in the interlinking of complicated groups; in the principal actors energy of dramatic action and expression not yet overstrained, as it came to be in the artist's later work; an incisive vigor of portraiture in the personages of the male bystanders; in the faces and figures of the women an equally vital grasp of the model, combined with that peculiar strain of haunting and melancholy grace which is this artist's own; the most expressive care and skill in linear draughtsmanship, the richest and most inventive charm in fanciful costume and decorative coloring, all combine to distinguish them. During this time of his stay in Rome (1481-82) Botticelli is recorded also to have painted another "Adoration of the Magi", his fifth or sixth embodiment of the same subject; this has been identified, no doubt rightly, with a picture now in the Hermitage gallery at St. Petersburg.

Returning to Florence towards the end of 1482, Botticelli worked there for the next ten years, until the death of Lorenzo de Medici in 1492, with but slight variations in manner and sentiment, in the now formed manner of his middle life. Some of the recorded works of this time have perished; but a good many have been preserved, and except in the few cases where the dates of commission and payment can be established by existing records, their sequence can only be conjectured from internal evidence. A scheme of work which he was to have undertaken with other artists in the Sala dei Gigli in the Palazzo Pubblico came to nothing (1483); a set of important mythologic frescoes carried out by him in the vestibule of a villa of Lorenzo de Medici at Spedaletto near Volterra in 1484 has been destroyed by the effects first of damp and then of fire. To 1482-83 belongs the fine altarpiece of San Barnabo (a Madonna and Child with six saints and four angels), now in the academy at Florence. Very nearly of the same time must be the most popular and most often copied, though very far from the best-preserved, of his works, the round picture of the Madonna with singing angels in the Uffizi, known from the text written in the open choirbook, as the "Magnificat." Somewhere near this must be placed the beautiful and highly finished drawing of "Abundance", now in the British Museum, as well as a small Madonna in Milan, and the fine full-faced portrait of a young man, probably some pupil or apprentice in the studio, at the National Gallery (No. 626). For the marriage of Antonio Pucci to Lucrezia Dini in 1483 Botticelli designed, and his pupils or assistants carried out, the interesting and dramatic set of four panels illustrating Boccaccio's tale of Nastagio degl' Onesti, which were formerly in the collection of Barker and are now dispersed. His magnificent and perfectly preserved altarpiece of the Madonna between the two saints John, now in the Berlin gallery, was painted for the Bardi chapel in the church of San Spirito in 1486. In the same year he helped to celebrate the marriage of Lorenzo Tornabuoni with Giovanna degli Albizzi by an exquisite pair of symbolical frescoes, the remains of which, after they had been brought to light from under a coat of whitewash on the walls of the Villa Lemmi, were removed in 1882 to the Louvre.

Within a few years of the same date (1485-88) should apparently be placed that second masterpiece of fanciful classicism done for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco's villa at Castello, the "Birth of Venus", now in the Uffizi, the design of which seems to have been chiefly inspired by the "Stanze" of Politian, perhaps also by the Pervigilium Veneris; together with the scarcely less admirable "Mars and Venus" of the National Gallery, conceived in the master's peculiar vein of virile sanity mingled with exquisite caprice; and the most beautiful and characteristic of all his Madonnas, the round of the "Virgin with the Pomegranate" (Uffizi). The fine picture of "Pallas and the Centaur", rediscovered after an occultation of many years in the private apartments of the Pitti Palace, would seem to belong to about 1488, and to celebrate the security of Florentine affairs and the quelling of the spirit of tumult in the last years of the power of the great Lorenzo (1488-90). "The Annunciation" from the convent of Cestello, now in the Uffizi, shows a design adapted from Donatello, and expressive, in its bending movements and vehement gestures, of that agitation of spirit the signs of which become increasingly perceptible in Botticelli's work from about this time until the end. The great altarpiece at San Marco with its predelle, commissioned by the Arte della Seta in 1488 and finished in 1490, with the incomparable ring of dancing and quiring angels encircling the crowned Virgin in the upper sky, is the last of Botticelli's altarpieces on a great scale. To nearly the same date probably belongs his deeply felt and beautifully preserved small painting of the "Last Communion of St. Jerome" belonging to the Marchese Farinola.

In 1490 Botticelli was called to take part with other artists in a consultation as to the completion of the façade of the Duomo, and to bear a share with Alesso Baldovinetti and others in the mosaic decorations of the chapel of San Zenobio in the same church. The death of Lorenzo de Medici in 1492, and the accession to chief power of his worthless son Piero, soon plunged Florence into political troubles, to which were by and by added the profound spiritual agitation consequent upon the preaching and influence of Girolamo Savonarola. Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de Medici, who with his brother Giovanni was in a position of political rivalry against their cousin Piero, continued his patronage of Botticelli; and it was for him, apparently chiefly between the years 1492 and 1495, that the master undertook to execute a set of drawings in illustration of Dante on a far more elaborate and ambitious plan than the little designs for the engraver which had been interrupted in 1481. Eighty-five of these drawings are in the famous manuscript acquired for the Berlin museum at the sale of the Hamilton Palace collection in 1882, and eleven more in the Vatican library at Rome. The series is one of the most interesting that has been preserved by any old master; revealing an intimate knowledge of and profound sympathy with the text; full of Botticelli's characteristic poetic yearning and vehemence of expression, his half-childish intensity of vision; exquisite in lightness of touch and in swaying, rhythmical grace of linear composition and design. These gifts were less suited on the whole to the illustration of the Hell than of the later parts of the poem, and in the fiercer episodes there is often some puerility and inadequacy of invention. Throughout the Hell and Purgatory Botticelli maintains a careful adherence to the text, illustrating the several progressive incidents of each canto on a single page in the old-fashioned way. In the Paradise he gives a freer rein to his invention, and his designs become less a literal illustration of the text than an imaginative commentary on it. Almost all interest is centered on the persons of Dante and Beatrice, who are shown us again and again in various phases of ascending progress and rapt contemplation, often with little more than a bare symbolical suggestion of the beatific visions presented to them. Most of the drawings remain in pen outline only over a light preliminary sketch with the lead stylus; all were probably intended to be finished in color, as a few actually are.

To the period of the Dante drawings (1492-97) would seem to belong the fine and finely preserved small round of the "Virgin and Child with Angels" at the Ambrosiana, Milan, and the famous "Calumny of Apelles" at the Uffizi, inspired no doubt by some contemporary translation of the text by Lucian, and equally remarkable by a certain feverish energy in its sentiment and composition, and by its exquisite finish and richness of execution and detail. Probably the small "St. Augustine" in the Uffizi, the injured "Judith with the head of Holofernes" in the Kaufmann collection at Berlin, and the "Virgin and Child with St. John" in London, are works of the same period.

Simone di Mariano, a brother of Botticelli long resident at Naples, returned to Florence in 1493 and shared Sandro's home in the Via Nuova. He soon became a devoted follower of Savonarola, and has left a manuscript chronicle which is one of the best sources for the history of the friar and of his movement. Sandro himself seems to have remained aloof from the movement almost until the date of the execution of Savonarola and his two followers in 1498. At least there is clear evidence of his being in the confidence and employ of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco so late as 1496 and 1497, which he could not possibly have been had he then been an avowed member of the party of the Piagnoni. It was probably the enforced departure of Lorenzo from Florence in 1497 that brought to a premature end the master's great undertaking on the illustration of Dante. After Lorenzo's return, following on the overthrow and death of Savonarola in 1498, we find no trace of any further relations between him and Botticelli, who by that time would seem to have become a declared devotee of the friar's memory and an adherent, like his brother, of the defeated side.

During these years of swift political and spiritual revolution in Florence, documents give some glimpses of him: in 1497 as painting in the monastery of Monticelli a fresco of St. Francis which has perished; in the winter of the same year as bound over to keep the peace with a neighbor living next to the small suburban villa which Sandro held jointly with his brother Simone in the parish of San Sepolcro; in 1499 as paying belated matriculation fees to the guild of doctors and druggists (of which the painters were a branch); and again in 1499 as carrying out some decorative paintings for a member of the Vespucci family. It has been suggested, probably with reason, that portions of these decorations are to be recognized in two panels of dramatic scenes from Roman history, one illustrating the story of Virginia, which has passed with the collection of Senatore Morelli into the gallery at Bergamo, the other a history of Lucretia formerly belonging to Lord Ashburnham, which passed into Gardner's collection at Boston. These and the few works still remaining to be mentioned are all strongly marked by the strained vehemence of design and feeling characteristic of the master's later years, when he dramatizes his own high-strung emotions in figures flung forward and swaying out of all balance in the vehemence of action, with looks cast agonizingly earthward or heavenward, and gestures of wild yearning or appeal. These characters prevail still more in a small Pietà at the Poldi-Pezzoli gallery, probably a contemporary copy of one which the master is recorded to have painted for the Panciatichi chapel in the church of Sta. Maria Maggiore; they are present to a degree even of caricature in the larger and coarser painting of the same subject which bears the master's name in the Munich gallery, but is probably only a work of his school.

The mystic vein of religious and political speculation into which Botticelli had by this time fallen has its finest illustration in the beautiful symbolic "Nativity", now in the National Gallery, with the apocalyptic inscription in Greek which the master has added to make his meaning clear (No. 1034). In a kindred vein is a much-injured symbolic "Magdalene at the foot of the Cross." in Lyons. Among extant pictures those which from internal evidence we must put latest in the master's career are three panels illustrating the story of St. Zenobius, of which one is at Dresden and the other two in a collection in London. The documentary notices of him after 1500 are few. In 1502 he is mentioned in the correspondence of Isabella d'Este, marchioness of Gonzaga, and in a poem by Ugolino Verino. In 1503-04 he served on the committee of artists appointed to decide where the colossal "David" of Michelangelo should be placed. In these and the following years we find him paying fees to the company of St. Luke, and the next thing recorded of him is his death, followed by his burial in the Ortaccio or garden burial ground of the Ognissanti, in May 1510.

The strong vein of poetical fantasy and mystical imagination in Botticelli, to which many of his paintings testify, and the capacity for religious conviction and emotional conversion which made of him an ardent, if belated, disciple of Savonarola, coexisted in him, according to all records, with a strong vein of the laughing humor and love of rough practical and verbal jesting which belonged to the Florentine character in his age. His studio in the Via Nuova is said to have been the resort, not only of pupils and assistants, of whom a number seem to have been at all times working for him, but of a company of more or less idle gossips with brains full of rumor and tongues always wagging. Vasari's account of the straits into which he was led by his absorption in the study of Dante and his adhesion to the sect of Savonarola are evidently much exaggerated, since there is proof that he lived and died, not rich indeed, but possessed of property enough to keep him from any real pinch of distress.

[2] Although lifelike, early Renaissance portraits of women also conform to an ideal of beauty. Most Florentine women, then as now, were brown-eyed brunettes, yet they are often portrayed with blond hair, ivory skin, and sparkling eyes. These portraits reflect a canon of beauty derived from literature, especially from sonnets written by Petrarch in the fourteenth century in praise of his beloved Laura. Beauty was closely linked to virtue in Renaissance thought: because physical beauty signified an inner beauty of spirit, a beautiful woman was seen as an agent who could draw man to love, and through love, to God.

A striking echo of Laura's portrait is Botticelli's Young Woman (Simonetta Vespucci?) in Mythological Guise. Her flowing golden tresses and braided hairpieces recall one of Petrarch's verses: "Breeze that surrounds those blond and curling locks, that makes them move...and scatters the sweet gold, then gathers it in lovely knots recurling...." Botticelli's portrait may fuse Laura's attributes with those of the renowned Florentine beauty, Simonetta Vespucci, Giuliano de' Medici's ladylove who died in 1476 at the age of twenty-three. The relatively large size of this painting possibly reflects another lost work: a portrait of Simonetta in the guise of the mythological goddess Athena, which Botticelli had painted on a standard that Giuliano carried in a ceremonial joust in Florence in 1475. [Virtue and Beauty: Leonardo's "Ginevra de' Benci" and Renaissance Portraits of Women | The exhibition surveyed the phenomenal rise of female portraiture in Florence from c. 1440 to c. 1540 and was on view in the West Building of the National Gallery of Art from 30 September 2001 through 6 January 2002].

[3]

[4] Piero di Cosimo (January 2, 1462 – 1521), an Italian Renaissance painter, was also known as Piero di Lorenzo. The son of a goldsmith, Piero was born in Florence and apprenticed under the artist Cosimo Rosseli, from whom he derived his popular name and whom he assisted in the painting of the Sistine Chapel in 1481.

In the first phase of his career, Piero was influenced by the Netherlandish naturalism of Hugo van der Goes, whose Portinari Triptych (now at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence) helped to lead the whole of Florentine painting into new channels. From him, most probably, Cosimo acquired the love of landscape and the intimate knowledge of the growth of flowers and of animal life. The manner of Hugo van der Goes is especially apparent in the Adoration of the Shepherds, at the Berlin Museum.

He journeyed to Rome in 1482 with his master, Rosselli. He proved himself a true child of the Renaissance by depicting subjects of Classical mythology in such pictures as the Venus, Mars, and Cupid, The Death of Procris, the Perseus and Andromeda series, at the Uffizi, and many others. Inspired to the Vitruvius' account of the evolution of man, Piero's mythical compositions show the bizarre presence of hybrid forms of men and animals, or the man learning to use fire and tools. The multitudes of nudes in these works shows the influence of Luca Signorelli on Piero's art.

During his lifetime, Cosimo acquired a reputation for eccentricity — a reputation enhanced and exaggerated by later commentators such as Giorgio Vasari, who included a biography of Piero di Cosimo in his Lives of the Artists. Reportedly, he was frightened of thunderstorms, and so pyrophobic that he rarely cooked his food; he lived largely on hard-boiled eggs, which he prepared 50 at a time while boiling glue for his artworks. He also resisted any cleaning of his studio, or trimming of the fruit trees of his orchard; he lived, wrote Vasari, "more like a beast than a man".

If, as Vasari asserts, he spent the last years of his life in gloomy retirement, the change was probably due to preacher Girolamo Savonarola, under whose influence he turned his attention once more to religious art. The death of his master Roselli may also have had an impact on Piero's morose elder years. The Immaculate Conception with Saints, at the Uffizi, and the Holy Family, at Dresden, illustrate the religious fervour to which he was stimulated by Savonarola.

With the exception of the landscape background in Rosselli's fresco of the Sermon on the Mount, in the Sistine Chapel, there is no record of any fresco work from his brush. On the other hand, Piero enjoyed a great reputation as a portrait painter: the most famous of his work is in fact the portrait of a Florentine noblewoman, Simonetta Vespucci, mistress of Giuliano de' Medici. According to Vasari, Piero excelled in designing pageants and triumphal processions for the pleasure-loving youths of Florence, and gives a vivid description of one such procession at the end of the carnival of 1507, which illustrated the triumph of death. Piero di Cosimo exercised considerable influence upon his fellow pupils Albertinelli and Bartolomeo della Porta, and was the master of Andrea del Sarto.

Vasari gave Piero's date of death as 1521, and this date is still repeated by many sources, including the Encyclopædia Britannica.[5] However, contemporary documents reveal that he died of plague on April 12, 1522.

[5] 'Here, Piero di Cosimo has chosen a portrait type which was already outmoded by the time he came to paint it (c. 1520). The profile view may have been borrowed from a medal portrait used by Piero as a model, since Simonetta Vespucci, whose latinized name appears on the strip along the bottom of the painting, had died of consumption in 1476.[5] Simonetta was the mistress of Giuliano de' Medici (1453-1478). Angelo Poliziano (1454-1494), a Florentine poet close to the Medici family, extols her grace and beauty in a renowned love poem: "La bella Simonetta". In the poem he compares her to a nymph frolicking with her playmates on a meadow:

"...Thus Amor sent his brightly burning spirits forth from eyes so sweet to fire the hearts of men.

A miracle it was

that I did not at once reduce to ash."

Poliziano eulogizes her "animated face", framed by loosely hanging golden hair - a symbol of Simonetta's virginal purity. In Piero di Cosimo's painting, in contrast, the young woman wears the elegantly plaited hair-style of a "Donna": a complex arrangement of braids decorated with pearls and intertwined with strings of beads. Her high, shaved forehead corresponds to a fashion in Italian, as well as Netherlandish, aristocratic circles in the last quarter of the fifteenth century. Unlike Antonio del Pollaiuolo's profile of a young woman'', painted c. 1465, almost a cameo-portrait against an even blue sky, Piero di Cosimo seeks to characterise Simonetta's mood by posing her against an atmospheric landscape. There is something gloomy in the repetitive, almost laminated outlines of the evening clouds, possibly evoking the mood of her early death. This corresponds to the withered tree on the left, a symbol which usually stands for death in Italian Renaissance landscape backgrounds. The motif is echoed by the snake wound around her necklace. Giorgio Vasari, who evidently was not acquainted with symbolism of this kind, saw in this an allusion to Cleopatra, who, according to Plutarch, had died from the bite of an asp. This explanation is unconvincing, however. It is more likely that the snake is a reference to the "hieroglyphic" symbolism of Egyptian "impresa". In the mythography of late Classical antiquity, the snake, especially when shown biting its own tail, was a symbol for eternity, or for time's rejuvenating cycle. It was therefore attributed to Janus, the god of the new year, and to Saturn (Kronos, whose name was often confused with time, Chronos), or "Father Time". In the inscription Simonetta is described as "Ianuensis" (belonging to Janus). The snake was also the symbol of Prudentia. Thus Simonetta is praised for her wisdom. Her contemporaries would not have been offended by her naked breasts. As in Titian's Venus at her Mirror, this motif may be seen as an allusion to the "Venus pudica", or "chaste" Venus. In Pans Bordone's allegories on the subject of lovers, executed c. 1550, it was a bridal symbol. Thus Simonetta is honoured not as Giuliano de' Medici's mistress, but as his betrothed, or perhaps even as his wife.' [Norbert Schneider]

|

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Simonetta Vespucci and Sandro Botticelli and , published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

|

|

Spring by Botticelli. The central figure is presumed to be a portrait of La Bella Simonetta.

Spring by Botticelli. The central figure is presumed to be a portrait of La Bella Simonetta.