| Domenico Veneziano (c. 1410 - 1461) |

| Domenico Veneziano was born about 1410, in Venice, but trained with Gentile da Fabriano in Florence and Rome. After Gentile's death he worked with Pisanello in Rome in the 1430s. |

, |

Domenico Veneziano stayed in Florence around 1432. Here he began to work as an independent artist, painting his first works between 1432 and 1437, the year he moved to Perugia to paint, as Vasari informs us, "a room in the house of the Baglioni family with frescoes that have been destroyed." The first painting Domenico worked on in Florence was the Carnesecchi Tabernacle, today in the National Gallery, London. The painting shows a dignified and aristocratic Madonna seated on an elegant throne decorated with splendid marble intarsia. The Child is standing on her lap, giving a sign of blessing. Above them, the foreshortened figure of God the Father is dispatching the dove of the Holy Spirit. The elaborate and accurate perspective construction of the throne, to some extent influenced by Paolo Uccello, is also indicative of another aspect of Domenico's style, his interest in the rules of perspective, for his art belongs entirely to the new language of the Renaissance. The choice of colours in the London painting is extraordinary: the delicate tones are emphasized by the bright and uniform lighting, widely praised by all art historians as one of the most truly original elements in Domenico's work. The Head of a Tonsured, Beardless Saint as well as Head of a Tonsured, Bearded Saint and The Virgin and Child Enthroned, in the collection of the National Gallery in London, are the surviving parts of a street tabernacle once on the Canto de' Carnesecchi, near the Piazza of Santa Maria Novella in Firenze, painted by Domenico Veneziano in the 15th century. The two heads of saints are fragments from the sides of the tabernacle. According to the painter and biographer Giorgio Vasari, this was one of Domenico's first works in Florence. Domenico Veneziano's assistant in 1439 was Piero della Francesca. Shortly after this work, characterized by the bold but not totally successful foreshortening of the throne, is the tondo of the Adoration of the Magi (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), probably executed for the Medici after the artist's return to Florence, in which solid handling of the perspective is enlivened by minute description of nature in the landscape, recalling probable Flemish prototypes and perhaps also memories of the artist's early training in the Veneto. From the same period is a vigorous portrait of a young man in the museum in Chambéry, usually attributed to Paolo Uccello. |

||||

| In the Madonna and Child in the Biblioteca Berenson near Florence, the forcefully defined figures stand out sharply against the precious damask of the background. The newly married art historians Bernard and Mary Berenson made their home at the Villa I Tatti near Florence in 1900. In the following years Mary, supervised the rebuilding of the villa and the creation of its elegant gardens. The Berensons pursued their work at I Tatti over a period of nearly six decades, and here they entertained a remarkable circle of friends: art historians ( Kenneth Clark, John Walker, John Pope-Hennessy), writers (Edith Wharton, Alberto Moravia), political thinkers (Walter Lippman, Gaetano Salvermini), musicians (Yehudi Menuhin) and countless other visitors from every part of the world. At I Tatti Bernard Berenson assembled a choice collection of Renaissance art, including works by Giotto, Sassetta, Domenico Veneziano, and Lorenzo Lotto. He also formed a prodigious art historical research library and photograph collection. When he died in 1959, he bequeathed the house, its contents, and the gardens to Harvard University as a Center for Renaissance Studies.[3] The Madonna and Child in the Berenson Collection is also similarly related to Florentine painting of the 1430s. For this reason it is normally dated at around the same period as the Carnesecchi Tabernacle. The gentle image of the Virgin is placed against a reddish brocade backdrop, creating a very elegant and courtly mood; she offers a flower to the plump little Child. Here, too, the lighting contributes peaceful intimacy to the scene. |

||||

| In his large tondo Adoration of the Magi there is a sumptuous display of ornament, and the figures clothed in fanciful garments are placed in a deeply receding and realistic landscape. Domenico Veneziano most certainly knew the paintings of his predecessors. The landscape in his Adoration of the Magi dating in 1438-1439 is similar to Gentile da Fabriano’s landscape as painted by Masaccio. The position of the holy family, the first king and the suit is similar to those in Masaccio, it is actually their mirror projection. The painting as a whole also reminds us of the mirror because of its shape which is – also a novelty – round. The same painting shape was also used by Sandro Botticelli in one of his early variations of the same motif, in the so called London's Adoration of the Magi which is time vise (1470-1475) much older than Domenico Veneziano’s. The man with a falcon among magi is supposed to be Piero de’ Medici. Falcon was his personal emblem. Peacock was a personal emblem of Giovanni di Cosimo de’ Medici. In a letter from Domenico Veneziano to Piero de' Medici, dated from Perugia in 1438, where he likewise resided for many years, he mentions his long connection with the fortunes of the Medici family, and begs to be allowed to paint an altar-piece for the head of that house. Between 1439 and 1441 he painted his masterpiece of the Adoration of the Magi. |

||||

| During the middle decades of the fifteenth century, the bust-length profile portrait enjoyed a remarkable popularity among the patrician classes of the Florentine republic. The Florentines used such stern and schematic self images to project a sense of their social status and civic responsibility and to convey to posterity an eternal vision of republican and family virtues. A rare, early example of this Florentine profile type is the Chrysler Museum portrait of 1440-55. The Latin inscription on the ledge at bottom identifies the sitter as "Michele Olivieri, Matteo's son," who was a member of a prominent Florentine merchant family. Though neither Michele Olivieri nor his father Matteo appears to have held high office in the Florentine government, Michele's grandfather, Ser Giovanni, served as prior in the city in 1349. The sitter's ceremonial attire — he wears a white, pleated doublet with fur collar, a rose-colored cape and a loosely tied, salmon-red turban — confirms his lofty social standing and helps to date the painting to the years after 1440. The pendant profile portrait of Matteo Olivieri is today in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Rediscovered by scholars in the early 1930s, the Oliveri pendants have been compared to three other, comparably designed Florentine male portraits (Musee des Beaux-Arts, Chambery; Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston; and another in the National Gallery of Art). The pendants were attributed early to Paolo Uccello (1397-1475), but more recent writers have placed them within the sphere of Domenico Veneziano. Some Florentine profile portraits were posthumous productoins, idealized evocations of departed family members. The Olivieri pendants served a similarly commemorative function. At the time these portraits were made, Michele was roughly sixty-five years old and Matteo already dead, yet both are portrayed as young men. The paintings were intended, then, as timeless "memory images" of father and son, which may have taken their place in the Olivieri's own portrait gallery of illustrious family members. |

Domenico Veneziano (attributed to), Portrait of Michele Olivieri, c. 1440-55, Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia |

|||

| The portrait of Matteo Olivieri is among the first from the Renaissance. During the late Middle Ages, depictions of individual donors had often been included in religious paintings, but it was not until the early fifteenth century that independent portraits were commissioned. The earliest ones are, like these, simple — even austere — profile views. Very likely, they were influenced by portrait busts and the profile heads on ancient gems and coins, which were avidly collected by Renaissance humanists. The popularity of the independent portrait was spurred by a new focus on the individual and an appreciation of individual accomplishments—a new conception of fame. Probably, the portrait is of Matteo Olivieri — his name appears on the ledge — and was originally paired with one of his son Michele, who may have commissioned both works. Though painted long after Matteo had died (he left a will in 1365), the portrait depicts a young man, as did the portrait of his son, who must have been at least sixty-five when the works were painted. Most portraits were probably commissioned as commemorations of the deceased by families who wished to remember them in the prime of life. As Renaissance art theorist Alberti noted, a portrait "like friendship can make an absent man seem present and a dead one seem alive."[°] In a subsequent phase the painter reveals his interest not only in the artistic language of Filippo Lippi but also in the sculptures of Donatello and Luca della Robbia. The sculptural qualities of the figures, as well as an increasing attention to ideals of classical beauty, characterize the Madonna of the Rose Bower in the Muzeul de Arta in Bucharest, sometimes assigned to the artist's earliest activity in Florence, but more likely executed during his second stay in Florence. The frescoes painted between 1439 and 1445 in the Florentine church of Sant Egidio are now lost; praised by Vasari as the most splendid undertaking in painting in Florence after the Brancacci chapel, the cycle was begun by Domenico and the young Piero della Francesca, who was then his workshop assistant, continued by Andrea del Castagno, and completed by Alesso Baldovinetti in 1461. |

||||

Santa Lucia de’ Magnoli Altarpiece

|

||||

Domenico Veneziano, The Madonna and Child with Saints, central panel from Santa Lucia de’ Magnoli Altarpiece, c. 1445, tempera on wood, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

|

||||

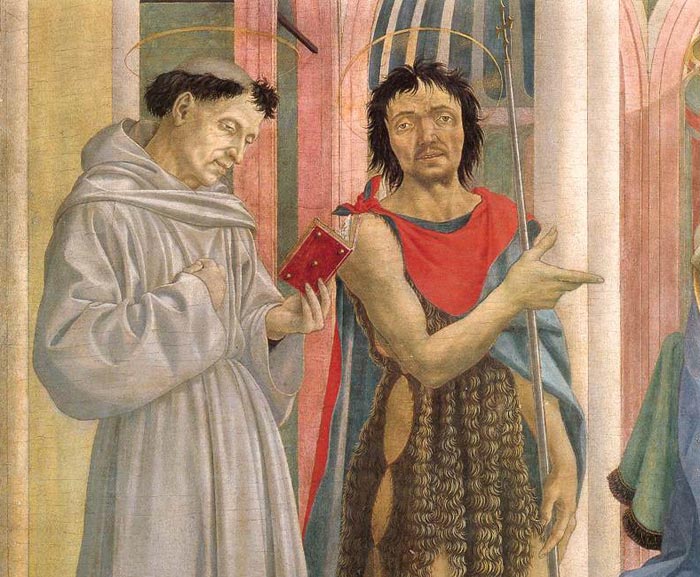

| Probably in the second half of the 1440s Domenico painted his masterpiece, the altarpiece for the church of Santa Lucia dei Magnoli, which represents, within a complex architectural setting, the Madonna and Child with four saints (now in the Galleria degli Uffizi) and related stories in the predella, dispersed among various museums. Probably very soon after this piece, a seminal work in the development of Florentine painting after mid-century and particularly important for artists such as Giovanni di Francesco, Alesso Baldovinetti, and the Master of Pratovecchio, Domenico painted the Madonna and Child in the National Gallery of Art in Washington and some other works which are documented but do not survive: two marriage chests done in Florence between 1447 and 1448 for Marco Parenti, and a standard, painted for the Compagnia di Sant Antonio Abate in Arezzo in 1450. The work, signed and dated about 1445, comes from the Florentine church of Santa Lucia dei Magnoli and shows the Madonna enthroned with Child among the saints (left to right) Francis, John the Baptist (whose face is the self-portrait of the painter), Zenobius and Lucy. The sacra conversazione is placed in a completely Renaissance architectural setting, where the perspective study get perfection with the foreshortening of the floor. The natural light and the absence of gold on the backgrond of the picture, make this altarpiece one of the first achievements of the new Renaissance art. The traditional tricusped frame of Gothic triptychs is transformed in the Magnoli Altarpiece into an elegant loggia decorated with lovely marble intarsia. Sheltered by this construction stands the throne, with the Madonna and Child and four saints. Each one of these characters has his own physical and moral individuality, conveyed not only by the very sculptural relief with which the beautiful faces are drawn, but also by the precise position they hold within the space so clearly defined by the architectural structure. If we compare this painting with the Berlin Adoration of the Magi, painted about five years earlier, we can see how Domenico's palette has changed: the dark and bright colours in the Berlin tondo, a legacy from Gentile and Pisanello, have been replaced by lighter colours and more delicate hues. But what really stands out in the Uffizi altarpiece is the presence of this pale and delicate light coming from a natural source, like an open window with a ray of warm sunlight streaming in, lighting up the peaceful composition and creating a shadow against the background, as evidence of its existence. This particular idea of lighting is Domenico's greatest debt to the art of Fra Angelico, and also one of his most extraordinary and original achievements. The strong realism of St Francis and St John the Baptist - especially the tortured image of St John - has been attributed to the influence of Castagno, but should be seen merely as a more general sign of Domenico being an artist of his times, an era dominated by the splendid sculpture of Ghiberti and Donatello. The images emphatically affirm the monumental qualities of the painter's style. St John the Baptist is extremely muscular, with powerful limbs and thick extremities; he looks out of the oainted space at the spectator, who is, in turn, drawn by John's gesture toward the enthroned Madonna. Mary and the Child turn back toward John, who is presented in full face. Saint Lucy is shown in sharp and magnificent profile on the extreme right, while Zenobius turns easily in three-quarter view, balancing John in importance, for both are patron saints of Florence. Veneziano does not forget the late Gothic element which reappears, for instance, in the precise description of all details of the brocade of St Zenobius's elegant cope. The Magnoli Altarpiece had five predella panels which are now in the museums of Washington, Cambridge and Berlin. They were probably originally arranged in the same order as the saints appear in the main panel, that is: The Stigmatization of St Francis, St John in the Wilderness (both in the National Gallery, Washington), Annunciation, St Zenobius Performs a Miracle (in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) and the Martyrdom of St Lucy (in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin). |

The Madonna and Child with Saints, central panel from Santa Lucia de’ Magnoli Altarpiece, c. 1445, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence  The detail shows St Francis and St John the Baptist.

|

|||

|

||||

Domenico Veneziano, Annunciation (predella panel from Santa Lucia de’ Magnoli Altarpiece), c. 1445, tempera on wood, 27 x 54 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge |

||||

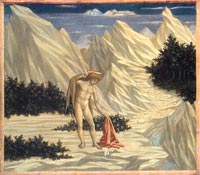

Saint John the Baptist in the Desert and Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata are from one of Domenico's major works, a large altarpiece in the church of Santa Lucia de' Magnoli in Florence, the Santa Lucia de’ Magnoli Altarpiece. They formed part of its predella, the lower tier of small scenes that typically illustrated events in the lives of the saints who appeared in the larger central altar panel above. Domenico's John the Baptist is unusual. Earlier artists had shown him as an older, bearded man with matted hair and clad in animal skins. Here, though, we see a youthful John at the very moment he is casting off the fine clothes of worldly life for a spiritual existence. His graceful figure, nude and modeled like an ancient statue, is one of the first embodiments of the Renaissance preoccupation with the art of ancient Greece and Rome. The figure is convincingly three-dimensional because the tones Domenico used for his flesh are graduated, one color blending continuously into the next. The landscape around the saint, however, belongs to an earlier tradition. Its sharp, stylized forms increase our appreciation for the desolation John is about to embrace in the stony wilderness; they dramatize his decision and give his action greater significance. Fra Carnevale, like Piero della Francesca, was deeply influenced by the light-washed colors of Veneziano's paintings. |

||||

Martyrdom of St Lucy (predella 5) c. 1445 Tempera on wood, 25 x 29 cm Staatliche Museen, Berlin |

||||

A Miracle of Saint Zenobius, set in Florence in the Borgo degli Albizzi, shows Saint Zenobius resuscitating a dead youth whose grieving mother had discovered his body when she returned from a pilgrimage. Like Saint John the Baptist in the Desert (cat. no. 22a), this picture formed part of the Saint Lucy Altarpiece. Its high-pitched drama offers a contrast to that scene. Veneziano exploited the possibilities offered him by the five predella scenes to demonstrate his mastery of the rich language of Renaissance painting. Note the way the figural action is staged in the foreground and the way the perspective focuses attention on the screaming face of the mother. The empty street punctuated by the eaves of the palaces helps create a mood of urgency. Only Donatello used perspective in a comparably emotive way. The Annunciation is the most successful of Domenico's experiments in rendering outdoor light: the pale morning light fills and defines the space of the courtyard, and the cool light on the broad plane of white wall heightens the sense of moment and loneliness in the two figures. |

||||

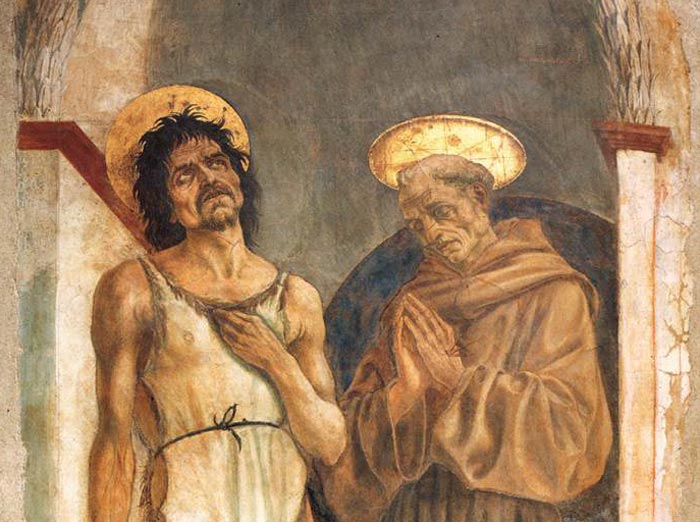

Domenico Veneziano, St John the Baptist and St Francis (detail) , 1454, detached fresco, 190 x 115 cm, Museo dell'Opera di Santa Croce, Florence |

||||

The evolution of Domenico Veneziano's style after the Magnoli Altarpiece is evident in the Santa Croce fresco, Saints John the Baptist and Francis, the artist's last known painting. Originally in the Cavalcanti Chapel, next to the choir in the church of Santa Croce, the fresco was removed from the wall in 1566, when the choir was torn down as part of the modernization project directed by Vasari. In 1954, for the exhibition called Four Masters of the Early Renaissance, the two saints were detached once again and placed in the museum of Santa Croce, where they still are today. The two full-length figures are shown under a trompe l'oeil barrel vault; they are very similar, both in form and in the pale colour tones, to the figures of John and Francis in the Magnoli Altarpiece, except that they are much more solidly modelled and the drawing is stronger, elements that most art historians attribute to the influence of Castagno's painting. And Vasari had actually attributed the fresco to Andrea. This change in Domenico's later works can probably be interpreted as an attempt to incorporate all the more recent developments in Florentine painting, which was at the time moving towards the linearism of Filippo Lippi and Andrea del Castagno. The Santa Croce saints are therefore to be seen as an example of how the artist succeeded in interpreting the influence of contemporary art, further evidence of the consistency of his stylistic development. |

||||

|

|

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency |

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Domenico Veneziano and is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. |