| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Nativity, 1490-95, Wood, 239 x 209 cm, San Domenico, Siena

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

| Francesco di Giorgio Martini |

|

|

|

| |

|

| Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Sienese painter, sculptor, architect and engineer, belongs to a select group of Renaissance practitioners, including Brunelleschi, Alberti, Michelangelo, Peruzzi, and, of course, Leonardo da Vinci, who excelled in several of the arts at the same time. A native of Siena, he may have been trained by Vecchietta (1410-1480), both a successful painter and sculptor. Francesco di Giorgio's early career, however, is too poorly documented to make any definitive judgments.

He appears in extant records for the first time in 1464, when he produced a wooden sculpture of St John the Baptist (Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena). In 1464 Francesco was charged with overseeing the intricate aqueduct system of Siena for a three-year period, and similar assignments as an engineer and architect continued to come for the remainder of his life, both in Siena and in other centres. His fellow Sienese painter Neroccio de' Landi (1447-1500) became his partner, perhaps as early as 1469, until litigation abruptly dissolved the relationship in 1475. In the 1470s Francesco painted two different versions of the Coronation of the Virgin, one in fresco for the ancient Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala, done in 1471 (destroyed), and another, originally for the Benedictine abbey church outside Siena at Monte Oliveto, which appears to have been painted c. 1472. Francesco signed a Nativity that was commissioned in 1475. Another Nativity from the 1490s is also attributed to the artist.

By the mid-1470s, Francesco di Giorgio's other skills were in strong demand, and in 1477 he was already in the service of the famed Federigo da Montefeltro of Urbino, primarily as a military engineer and architect. He built a great chain of fortifications for the Duke of Urbino, and he is credited with inventing the landmine. He also designed relief sculpture, intarsia decorations, medals, and war machines for his patron.

Francesco di Giorgio was in Naples in 1479 and in 1480. In 1484 he began his most famous building, the centrally designed Church of the Madonna del Calcinaio outside Cortona. Returning to Siena from time to time during the same period, he continued to receive various official commissions, including the bronze angels for the high altar of the Sienese Cathedral (finished in 1498), but no paintings are recorded later in his career. Francesco, summoned to Milan to give advice on how to design the dome of the Cathedral, came into contact with Leonardo da Vinci, who later owned and annotated one of Francesco's manuscripts.

The Sienese artist, along with important Florentines and a few other "foreigners," participated in a competition for designing a façade of the Cathedral of Florence. Back in Naples during the 1490s, he continued to be active in Urbino. In 1498 he finally returned to Siena for good when he was made capomaestro (head) of the works at the Cathedral. Francesco died in Siena toward the end of 1501, leaving behind, in addition to the works already mentioned, a series of manuscripts of the greatest importance devoted to architecture and engineering. No documentation confirms that he continued to paint after the Nativity, although critics usually assume later activity, including the magnificent newly discovered essentially monochromatic frescoes in the Bichi Chapel of Sant'Agostino in Siena which have been attributed to him.

Late in life Francesco di Giorgio may have turned to painting again, following work done in bronze relief, most famous of which is the Deposition in Venice, and four bronze angels for Siena Cathedral, but the attributions made for a late period are full of problems since Sienese painting toward the end of the fifteenth century has not yet been carefully studied. Outsiders begin to dominate the local scene. Perugino, Pinturicchio, and Signorelli, all active in Siena, overshadowed Francesco as a painter.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

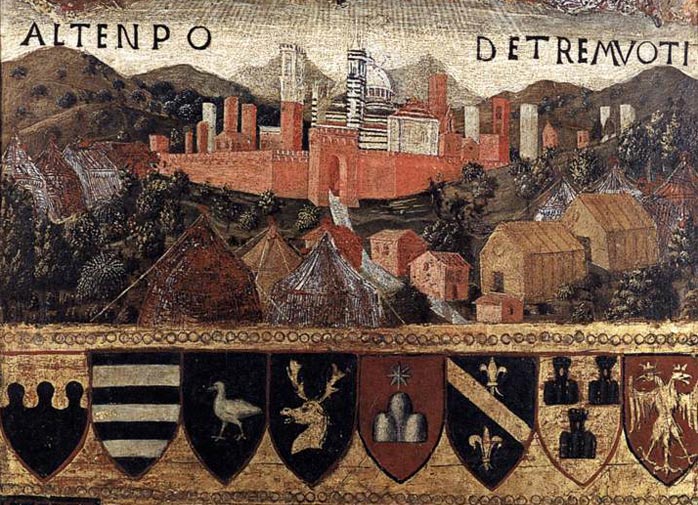

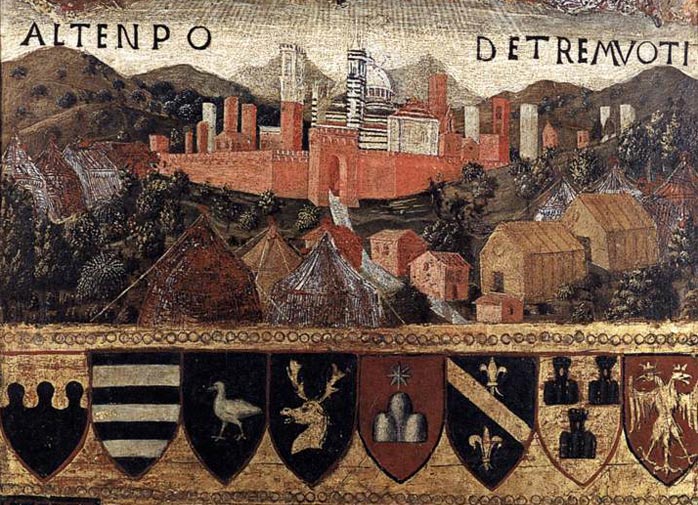

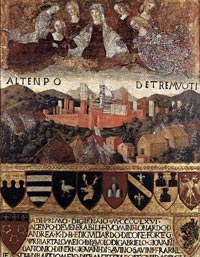

Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Madonna del Terremoto, detail, 1467, Archivo di Stato, Siena

|

The typical tablet from the Biccherna (revenue office) has a votive subject: the Virgin as intercessor to protect the city against earthquake. The contribution of an anonymous assistant referred to as "Fiduciario de Francesco" is assumed.

The Biccherna panels offer a history of Sienese art in miniature, over the course of which you can watch the Byzantine formality yield to a Gothic sense of realism, then supplanted by Renaissance one-point perspective, and so on. The panels also offer crucial historical information, showing the monks and nobles who served as tax officers.

Especially in later years, the panel was given over to a depiction of an important event in Siena during the six-month period of that codex of records. The panel shown above, by Francesco di Giorgio Martini, shows the city of Siena during a series of earthquakes in August 1466. You can see what the Duomo looked like and how the towers of Siena were more numerous and much taller in that period. The Sienese, fearing that those towers were going to collapse if the earthquakes continued, left the city in large numbers and lived in temporary shelters, which are shown in the foreground.

Beginning as a talented young painter, fully integrated within Sienese tradition, Francesco di Giorgio Martini ended as the most famous architect, engineer and 'universal man' of his era. His beautiful little Biccherna cover, painted in his late twenties, draws effortlessly on an accumulated imagery of the city that goes back to the early trecento (as does the Biccherna form itself). Towers and palaces rise up, surmounted by the striped Cathedral and the tower of the Palazzo Pubblico, all contained within the circuit of the wall, its brick transformed to a hotter pink, as though lit by a setting sun. Shaken by earthquakes, the inhabitants have moved outside into a tented camp. But the ever-protective Virgin (who resembles earlier Madonnas by Francesco's master Vecchietta, and whose angel-attendants recall in turn those of Vecchietta's teacher, Sassetta) still keeps covenant with her city. In the long lineage of Sienese civic images, Francesco's is perhaps the last that is truly memorable.

Art in Tuscany | Sienese Biccherna Covers | Biccherne Senesi |

|

Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Madonna del Terremoto, 1467, Archivo di Stato, Siena |

| |

|

|

| The Nativity with two angels, Sts Bernard and Thomas of Aquino is the only signed work of the Sienese master. (It is signed 'Francisc. Georgii insit' at left bottom.)

Francesco di Giorgio's interpretation of the Nativity is more closely related to depictions of the Adoration of the Child by the Virgin. Unlike those by Leonardo, Filippino Lippi, and Botticelli, this interpretation includes two saints on the left, in addition to the Holy Family accompanied by two angels. The event is set in an open landscape, with a particularly elaborate distant view in the upper left background of this lunette shaped panel. Behind the angels, a very simplified shed constructed out of a handful of wooden beams extends from an outcropping of rock.

In the short time between the Coronation and the Nativity, more properly an Adoration of the Child, commissioned in 1475 and presumably finished a year later, we see a shift that may signal a new phase in Francesco's development. But the number of paintings that can be attributed to him is so small that his evolution as a painter is virtually impossible to define. The Nativity is a more confident and less crowded composition than the Coronation. The radically twisted St Joseph in the centre, with his active movement, is an ambitious restatement of the Christ from the earlier picture. The sacred figures, including St Bernard and St Thomas (not Sts Bernardine and Ambrose, as their embossed inscriptions added in the nineteenth century would have it) with Joseph and Mary, form a flattened arc in space around an alert, open-eyed Child who rests His head on a pillow, which is formally related to the picture plane.

Francesco's treatment of the drapery gives the impression of having been based on careful studies, particularly noticeable in the figure of St Bernard. The figures, all on the same plane, are preceded by a bit of bare terrain. Directly behind the manger, a simple lean-to is attached to an outcropping of rock, with a segment of a classical building in a decaying state. Still farther in the distance is a well-articulated landscape with a local Sienese flavour. The two angels standing casually on the right are tall, weightless images enrapt in their own dreams.

The detail shows St Bernard and St Thomas of Aquino (not Sts Bernardine and Ambrose, as indicated by their embossed inscriptions added in the nineteenth century) on the left side of the painting.

|

|

Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Nativity, 1475, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena

St Bernard and St Thomas of Aquino

|

The Chapel of Saint Catherine of Siena in the Basilica of San Domenico in Siena, preserves the remains of the head of the saint, kept on the wonderful marble altar, the work of the sculptor Giovanni di Stefano (1469). The chapel is entirely covered in oils and wall paintings of very high merit, amongst which, on the sides of the altar, are two famous masterpieces by Sodoma, from 1526, the Rapture of Saint Catherine and the Eucharistic Vision. On the other side of the chapel, there is one of the few pictorial works by Francesco di Giorgio Martini, the Adoration of the Shepherds (1475-80).

The altarpiece is completed by a lunette attributed to Matteo di Giovanni and has altar steps painted by Bernardino Fungai. As such it sums up the Sienese school in the late fifteenth century. After his years in Urbino working as an architect, Francesco di Giorgio took up painting once more. The evolution in his style compared to his earlier work is obvious. The artist had by now fully mastered the depiction of space. The figures are scattered, paired into couples whose movements counterbalance each other.Colours are carefully juxtaposed. The grandiose ruined arch that dominates the scene showed Francesco di Giorgio's love of the classical world which he depicted with the deft strokes of an architectural drawing. |

|

Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Nativity, 1490-95, Wood, 239 x 209 cm, San Domenico, Siena

|

| |

|

|

Tuscan architects developing the principles laid down by Brunelleschi, constructed important churches in the last years of the 15th century. These include Santa Maria delle Carceri, at Prato, by Giuliano da Sangallo, and Santa Maria del Calcinaio, near Cortona, by Frencesco di Giorgio. Both these resemble the experiments with centrally planned churches being carried out in Milan by Leonardo and Bramente, and we know that Francesco di Giorgio was personally acquainted with Leonardo. In these churches we see the culmination of the Early Renaissance ideals of classical lightness and purity.

Francesco di Giorgio Martini was one of the most interesting later Quattrocento architects' and a visionary architectural theorist. As a military engineer he executed architectural designs and sculptural projects and built almost seventy fortifications for the Federico da Montefeltro, Count (later Duke) of Urbino, for whom he was working in the 1460s, building city walls as at Iesi and early examples of star-shaped fortifications.

Santa Maria delle Grazie al Calcinaio was built in 1484-1515 by Francesco di Giorgio Martini in connection with an alleged miracle-performing image of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the "Madonna del Calcinaio". This image was originally painted on the timbers of a lime-vat, a calcinaio, hence the name.

The shoemakers' guild, the proprietor of the tannery, decided to erect a "holy temple" as a result of the increased devotion that also manifested itself in the continuous donation of alms by the devout.

The chosen location posed uncommon difficulties for the construction due to the steepness of the land and the stream that flowed through it. These and other problems were brilliantly solved by Francesco di Giorgio Martini, the architect chosen by Luca Signorelli at the request of the shoemakers' guild. Martini accepted the commission and drew up the project that very year, 1484. Work started in 1485 and the church had already assumed its final appearance, at least externally, by the end of the first quarter of the 16th century.

The church consists of a nave flanked by side chapels with a transept and cupola at the intersection of the equal arms of the presbytery. It was laid out by Martini with the rigorous and clear application of Renaissance architectural principles of proportion and perspective. This space resounds with Albertian echoes and is not immune to Brunelleschian assonance, but Francesco di Giorgio's construction is completely original, so much so as to represent one of the highest levels of Renaissance spatial synthesis. The outside of the building, though seriously degraded due to the deterioration of the stone material, appears to the visitor to be an imposing block that preannounces by its sober decorations the geometric rationality that is so evident in the interior. The ample extensions of surfaces are divided into horizontal and vertical lines by string-course moldings and pilasters and are animated by gabled windows.

|

|

Santa Maria del Calcinaio, near Cortona

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Trattati di Architettura, Ingegneria e Arte Militare, a cura di Corrado Maltese, Ed. Il Polifilo, Milano, 1967.

Volpe, Gianni, Francesco di Giorgio : architetture nel ducato di Urbino, 1991

F. Paolo Fiore, Citta e macchine del '400 net disegni di Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Florence 1978.

Martini, Francesco di Giorgio, 1439-1502

AA.VV., Nel segno di Federico, Ed. Bolis 1984.

Ralph Toledano, Francesco di Giorgio Martini pittore e scultore, Electa, Milano 1987.

Fabio Mariano, Francesco di Giorgio Martini: la Pratica Militare, Edizioni QuattroVenti, Urbino, 1989.

Francesco di Giorgio architetto, a cura di Francesco Paolo Fiore e Manfredo Tafuri, Ed. Electa, Milano 1993.

Piero Torriti, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Ed. Giunti 1993.

|

[1] San Domenico (St. Dominic's Basilica) is a vast brick church in Siena. Founded by the Dominicans in 1125 as part of their friary, San Domenico is closely associated with St. Catherine of Siena. The raised chapel off the west end (to the right as you enter) preserves the only genuine Portrait of St. Catherine, painted by her friend and contemporary Andrea Vanni. The Cappella di Santa Caterina (Chapel of St. Catherine) halfway down the right wall was frescoed with scenes from the saint's life. All except the right wall (where in 1593 Francesco Vanni painted Catherine performing an exorcism) were frescoed by Sodoma in 1526. At the end of the nave, on the right, is the Nativity by Francesco di Giorgio Martini dominated by a crumbling Roman triumphal arch in the background and a Pietà above.

The Archivio di Stato in Siena is housed in the former palazzo of the Piccolomini family. The collection includes an incredibly complete set of tax and customs records for the city of Siena, going back to the 13th century. The records of the Biccherna and Gabella, as they were called, were bound into codices every six months, and the city government began to commission painted wooden panels as covers for these codices. Over the city's history, these panels were commissioned from the leading Sienese artists, a commitment to local art that continues today in the commissioning of the Palio, the standard that is the prize of the famous horse race of the same name, from a local artist.

The Biccherna panels offer a history of Sienese art in miniature, over the course of which you can watch the Byzantine formality yield to a Gothic sense of realism, then supplanted by Renaissance one-point perspective, and so on. The panels also offer crucial historical information, showing the monks and nobles who served as tax officers.

Especially in later years, the panel was given over to a depiction of an important event in Siena during the six-month period of that codex of records. The panel shown above, by Francesco di Giorgio Martini, shows the city of Siena during a series of earthquakes in August 1466. You can see what the Duomo looked like and how the towers of Siena were more numerous and much taller in that period. The Sienese, fearing that those towers were going to collapse if the earthquakes continued, left the city in large numbers and lived in temporary shelters, which are shown in the foreground.

Chiesa di Santa Maria delle Grazie al Calcinaio | web.rete.toscana.it

|

| |

The hidden secrets of southern Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Residency for writers and artists

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, giardino |

|

Cypress trees between San Quirico d'Orcia and Montalcino

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pienza |

|

Montefalco |

|

|

|

|

|

Siena, Palazzo Publico |

|

Siena, Duomo |

|

Val d'Orcia |

Cortona is an attractive place to spend a day or two with great art, great atmosphere, stupendous views to Lake Trasimeno and the Val di Chiana. Cortona also boasts one of the earliest convents founded by Saint Francis (1211), hidden in an enchanting gorge nearby. It also has some beautiful churches, such as "Madonna del Calcinaio", designed and built by Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1485) and a distinguished art gallery, il Museo Diocesano, housing works by Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca and his pupil Luca Signorelli, a native of Cortona.

Cortona was s a well-known Umbrian hill town before Frances Mayes wrote about renovating her house, “Casa Bramasole”, near here. The Cathedral is one of the oldest, if not the oldest church in town. The church was built in the 4th century at the dawn of the Christian age on the site of a pre-existing pagan temple. The church stands on the remains of the Etruscan and medieval walls running from the Porta Santa Maria gate to the Porta Colonia gate. Around the year 1000 the romanesque parish church of Santa Maria was built on the site of the previous church; the parish church was later remodelled by Nicola Pisano in 1262. The construction of the current church was started on June 9 1481; construction ended in 1507 and the church was consecrated a cathedral on June 9 1508.

The attribution of the original design to Giuliano da Sangallo and the school of Brunelleschi is still, in the absence of relevent documents, under debate.

The Santa Maria Nuova church stands lofty in a small dell located to the north-west of the town on the side of the road that once connected the Porta Colonia gate with the Franciscan Convent of Le Celle. Its construction was started in 1550 in an area where Etruscan remains were found to designs by architect Sensi, known as Cristofanello and went on in the following years under the direction of Giorgio Vasari that introduced substantial changes to the original project. Except for the dome the costruction ended in 1586; the church was consecrated a collegiate church in 1610 by bishop Bardi. In 1786 arch-duke Pietro Leopoldo suppressed the collegiate church that had in the meanwhile received the “distinguished” title and was demoted to priory.

San Niccolò

The San Niccolò church was built in the 15th century and features an elegant portico on the façade and on the left hand side. The church has a 15th century exterior appearance and is topped by an elegant triple bell bell-gable; the interior features three altars and on the side walls you will be able to see some 18th century wooden benches used by the members of the local Compagnia; the episcopal coat of arms of San Niccolò is painted on all benches. The church houses outstanding works of art amongst which a masterpiece by Luca Signorelli standing above the main altar and portraying the deposition of Christ from the Cross. A small chapel probably built to house the wooden statue of Christ walking to the Calvary opens on the right hand side of the entrance.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()