| |

|

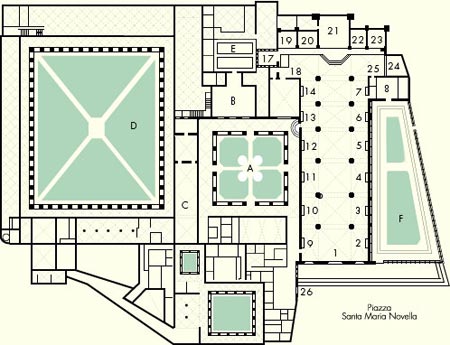

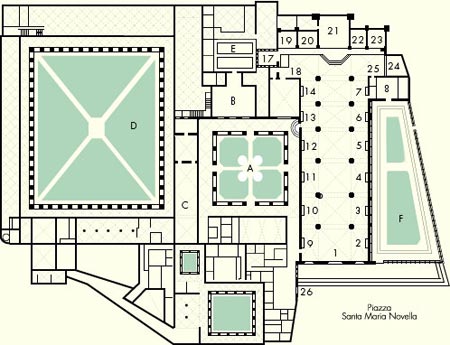

The Dominican monks, Sisto and Ristoro, are traditionally credited with the planning and construction of the Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. The plan of the building, a Latin cross with square chapels jutting out from the east side of the transept, was used for Franciscan models. The dynamic concept differs, from the slender cross vaults to acute pointed arches separating the nave, but with a greater spatial unity.

|

|

1. Facade (Giovan Battista Alberti)

2. Martyrdom of Saint Laurence (Girolamo Macchietti)

3. Adoration of the Shepherds (Giovan Battista Naldini)

4. Presentation in the temple (Giovan Battista Naldini)

5. Descent from the Cross (Giovan Battista Naldini)

6. The Predictions of Vincent Ferrer (Jacopo Coppi del Meglio)

7. Jacopo Ligozzi

8. Cappella della Pura (Wooden crucifix by Baccio da Montelupo)

9. Resurrection of Lazarus (Santi di Tito)

10. The Good Samaritan (Alessandro Allori)

11. The Holy Trinity (Masaccio)

12. Madonna of the Rosary ((Giorgio Vasari)

13. Altar: Poccetti

14. San Giacinto (Alessandro Allori)

15. Pulpit-Filippo Brunelleschi / Buggiano

16. Sacresty

17. Chapel Strozzi di Mantova (Frescoes by Nardo di Cione)

18. Chapel del Campanile

19. Chapel Gaddi

20. Chapel Gondi

21. Chapel Maggiore (Tornabuoni)

22. Chapel of Filippo Strozzi

23. Chapel Bardi

24. Chapel Rucellai

25. Buste de Saint Antonino

26. Way to the Cloisters |

A. Green Cloister

B. Spanish Chapel |

C. Refectorium

D. Grand Cloister

|

E. Chiostrino dei Morti

F. Burial Ground |

|

|

| History

|

The Basilica of Santa Maria Novella was called Novella (New) because it was built on the site of the 9th-century oratory of Santa Maria delle Vigne. When the site was assigned to Dominican Order in 1221, they decided to build a new church and an adjoining cloister. The church was designed by two Dominican friars, Fra Sisto Fiorentino and Fra Ristoro da Campi. Building began in the mid-13th century (about 1246), and was finished about 1360 under the supervision of Friar Iacopo Talenti with the completion of the Romanesque-Gothic bell tower and sacristy. At that time, only the lower part of the Tuscan gothic facade was finished. The three portals are spanned by round arches, while the rest of the lower part of the facade is spanned by blind arches, separated by pilasters, with below Gothic pointed arches, striped in green and white, capping noblemen's tombs. This same design continues in the adjoining wall around the old churchyard. The church was consecrated in 1420.

On a commission from Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai, a local textile merchant, Leone Battista Alberti designed the upper part of the inlaid black and white marble facade of the church (1456–1470). He was already famous as the architect of the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini, but even more for his seminal treatise on architecture De Re Aedificatoria, based on the book De Architectura of the classical Roman writer Vitruvius. Alberti had also designed the facade for the Rucellai Palace in Florence.

Alberti attempted to bring the ideals of humanist architecture, proportion and classically-inspired detailing, to bear on the design while also creating harmony with the already existing medieval part of the facade. His contribution consists of a broad frieze decorated with squares and everything above it, including the four white-green pilasters and a round window, crowned by a pediment with the Dominican solar emblem, and flanked on both sides by enormous S-curved volutes. The four columns with Corinthian capitals on the lower part of the facade were also added. The pediment and the frieze are clearly inspired by the antiquity, but the S-curved scrolls in the upper part are new and without precedent in antiquity. The scrolls (or variations of them), found in churches all over Italy, all find their origin here in the design of this church.

The frieze below the pediment carries the name of the patron : IOHAN(N)ES ORICELLARIUS PAU(LI) F(ILIUS) AN(NO) SAL(UTIS) MCCCCLXX (Giovanni Rucellai son of Paolo in the blessed year 1470).

|

| Interior

|

The vast interior is based on a basilica plan, designed as a Latin cross and is divided into a nave, two aisles with stained-glass windows and a short transept. The large nave is 100 metres long and gives an impression of austerity. There is a trompe l'oeil-effect by which this nave towards the apse seems longer than its actual length. The slender compound piers between the nave and the aisles are ever closer when you go deeper into the nave. The ceiling in the vault consists pointed arches with the four diagonal buttresses in black and white.

The interior also contains corinthian columns that were inspired by the Classical era of Greek and Roman times.

The stained-glass windows date from the 14th and 15th century, such as 15th century Madonna and Child and St. John and St. Philip (designed by Filippino Lippi), both in the Filippo Strozzi Chapel. Some stained glass windows have been damaged in the course of centuries and had to be replaced. The one on the facade, a depiction of the Coronation of Mary dates from the 14th century, based on a design of Andrea Bonaiuti.

The pulpit, commissioned by the Rucellai family in 1443, was designed by Filippo Brunelleschi and executed by his adopted child Andrea Calvalcanti. This pulpit has a particular historical significance, because from this pulpit the first attack came on Galileo Galilei, leading eventually to his indictment.

The Holy Trinity, situated almost halfway in the left aisle, is a pioneering early renaissance work of Masaccio, showing his new ideas about perspective and mathematical proportions. Its meaning for the art of painting can easily be compared by the importance of Brunelleschi for architecture and Donatello for sculpture. The patrons are the kneeling figures of the judge and his wife, members of the Lenzi family. The cadaver tomb below carries the epigram: "I was once what you are, and what I am you will become".

Of particular note in the right aisle is the Tomba della Beata Villana, a monument by Bernardo Rossellino in 1451. In the same aisle, you can find the tombs of the Bishop of Fiesole by Tino di Camaino and another one by Nino Pisano.

|

| The Tornabuoni Chapel

|

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Nativity of Mary, fresco in the Cappella Tornabuoni, Santa Maria Novella

|

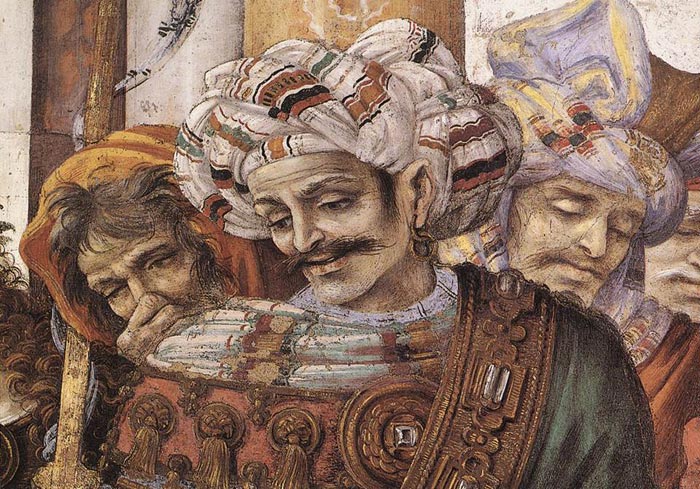

The Tornabuoni Chapel (Italian: Cappella Tornabuoni) is the main chapel (or chancel) in the church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy. It is famous for the extensive and well-preserved fresco cycle on its walls, one of the most complete in the city, which was created by Domenico Ghirlandaio and his workshop between 1485 and 1490.

The main chapel of Santa Maria Novella was first frescoed in the mid-14th century by Andrea Orcagna. Remains of these paintings were found during restorations in the 1940s: these included, mostly in the vault, figures from the Old Testament. Some of these were detached and can be seen today in the Museum of the church.

By the late 15th century, Orcagna's frescoes were in poor condition. The Sassetti, a rich and powerful Florentine family who were the bankers of the Medici, had long held the right to decorate the main altar of the chapel, while the walls and the choir had been assigned to the Ricci family. However, the Ricci had never recovered from their bankruptcy in 1348, and so they arranged to sell their rights to the choir to the Sassetti. Francesco Sassetti wanted the new frescoes to portray stories of St. Francis of Assisi. However, the Dominicans, to whom Santa Maria Novella was entrusted, refused. Sassetti therefore moved the commission to the church of Santa Trinita, where Ghirlandaio executed one of his masterworks, the Sassetti Chapel. The rights to the chapel in Santa Maria Novella that were lost by the Sassetti were then sold by the Ricci to Giovanni Tornabuoni.

Ghirlandaio, who then had the largest workshop in Florence, did not lose the commission however, because on September 1, 1485 Giovanni Tornabuoni commissioned him to paint the main chapel, this time with the lives of the Virgin and St. John the Baptist, patron of Tornabuoni and of the city of Florence. It is possible that the new scenes followed the same pattern as Orcagna's.

Ghirlandaio worked to the frescoes from 1485 to 1490, with the collaboration of his workshop artists, who included his brothers Davide and Benedetto, his brother-in-law Sebastiano Mainardi and, probably, the young Michelangelo Buonarroti. The windows were also executed according to Ghirlandaio's design.

The cycle portrays on three walls the Life of the Virgin and the Life of St John the Baptist, the patron saint of Florence. The left and right walls each have three rows, each divided into two rectangular scenes framed by fictive architecture, and surmounted by a large lunette beneath the vault. Each side wall has a total of seven narrative scenes which are read beginning from the bottom.

The chancel wall has a large mullioned window of three lights with stained glass, provided in 1492 by Alessandro Agolanti after Ghirlandaio's design. On the lower part of the wall is a donor portrait of Giovanni Tornabuoni and his wife Francesca Pitti, while on either side of the window are four smaller scenes portraying Dominican saints. Above the window is another large lunette, containing the Coronation of the Virgin. In the vault are depicted the Four Evangelists.

Art in Tuscany | Domenico Ghirlandaio | The Tornabuoni Chapel

|

|

The Tornabuoni Chapel

Domenico Ghirlandaio: Zachariah in the Temple [detail]: Marsilio Ficino, Cristoforo Landino, Angelo Poliziano and Demetrios Chalkondyles Domenico Ghirlandaio: Zachariah in the Temple [detail]: Marsilio Ficino, Cristoforo Landino, Angelo Poliziano and Demetrios Chalkondyles

|

|

|

|

| Filippo Strozzi Chapel

|

|

Filippino Lippi, St Philip Driving the Dragon from the Temple of Hieropolis (detail), Filippo Strozzi Chapel

|

The Filippo Strozzi Chapel is situated on the right side of the main altar. The Strozzi Chapel was the place where the first tale of the Decamerone by Giovanni Boccaccio began, when seven ladies decided to leave the town, and flee from the Black Plague to the countryside. The series of frescoes from Filippino Lippi depict the life of Philip the Apostle and James the Apostle. They were completed in 1502. On the right wall is the fresco St Philip Driving the Dragon from the Temple of Hieropolis and in the lunette above it, the Crucifixion of St Philip. On the left wall is the fresco St John the Evangelist Resuscitating Druisana and in the lunette above it The Torture of St John the Evangelist. Adam, Noah, Abraham and Jacob are represented on the ribbed vault. Behind the altar is the tomb of Filippo Strozzi with a sculpture by Benedetto da Maiano (1441).

The bronze crucifix on the main altar is by Giambologna (16th century). The choir (or the Cappella Tornabuoni) contains another series of famous frescoes, by Domenico Ghirlandaio and his apprentice the young Michelangelo (1485–1490). They represent themes from the life of the Virgin and John the Baptist, situated in Florence of the late 15th century. Several members of important Florentine families were portrayed on these frescoes. The vaults are covered with paintings of the Evangelists. On the back wall are the paintings Saint Dominic burns the Heretical Books and Saint Peter's Martyrdom, the Annunciation, and Saint John goes into the Desert.

The stained-glass windows were made in 1492 by the Florentine artist Alessandro Agolanti, known also as il Bidello, based on cartoons by Ghirlandaio.

Art in Tuscany | Filippino Lippi | The Strozzi Chapel in Basilica of Santa Maria Novella in Florence

|

|

St Philip Driving the Dragon from

the Temple of Hieropolis (detail) |

Gondi Chapel

|

|

|

This chapel, designed by Giuliano da Sangallo, is situated on the left side of the main altar and dates from the end of the 13th century. Here, on the back wall, is the famous wooden Crucifix by Brunelleschi, one of his very few sculptures. The legend goes that he was so disgusted by the "primitive" Crucifix of Donatello in the Santa Croce church, that he made this one. The vault contains fragments of frescoes by 13th-century Greek painters. The polychrome marble decoration was applied by Giuliano da Sangallo (ca.1503). The stained-glass window is recent and dates from the 20th century.

|

Cappella Strozzi di Mantova

|

|

|

The Cappella Strozzi di Mantova is situated at the end of the left transept. The frescoes were commissioned by Tommaso Strozzi, an ancestor of Filippo Strozzi, to Nardo di Cione (1350–1357). The frescoes are inspired by Dante's Divine Comedy: Last Judgment (on the back wall; including a portrait of Dante), Hell (on the right wall) and Paradise (on the left wall). The main altarpiece of The Redeemer with the Madonna and Saints was done by his brother Andrea di Cione, better kwown as Orcagna. The large stained-glass window on the back was made from a cartoon by the brothers Andrea and Nardo di Cione.

|

Della Pura Chapel

|

|

|

The Della Pura Chapel is situated north of the old cemetery. It dates from 1474 and was constructed with Renaissance columns. It was restored in 1841 by Baccani. On the left side there is a lunette with a 14th century fresco Madonna and Child and St. Catherine. There is a wooden crucifix by Baccio da Montelupo (1501) on the front altar.

|

Rucellai Chapel

|

|

|

The Rucellai Chapel, at the end of the right aisle, dates from the 14th century. It houses, besides the tomb of Paolo Rucellai (15th century) and the marble statue of the Madonna and the Child by Nino Pisano, several art treasures such as remains of frescoes by the Maestro di Santa Cecilia (end 13th - beginning 14th century). The panel on the left wall, the Martyrdom of Saint Catherine, was painted by Giuliano Bugiardini (with possibly assistance by Michelangelo). The bronze tomb, in the centre of the floor, was made by Ghiberti in 1425.[3]

|

Bardi Chapel

|

|

|

The Bardi Chapel, the second chapel on the right of the apse, was founded by Riccardo Bardi and dates from early 14th century. The high-relief on a pillar on the right depicts Saint Gregory blessing Riccardo Bardi. The walls show us some early 14th century frescoes attributed to Spinello Aretino. The Madonna del Rosario on the altar is by Giorgio Vasari (1568).

|

Sacristy

|

|

|

The sacristy, at the end of the left aisle, was built as the Chapel of the Annunciation by the Cavalcanti family in 1380. Now it houses again, after a period of fourteen years of cleaning and renovation, the enormous painted Crucifix with the Madonna and John the Evangelist, an early work by Giotto. He had rediscovered the ideal proportions for the human body, as established by the Roman architect Vitruvius (1st century AD, see also : Vitruvian Man). The sacristy is also embellished by a glazed terra cotta and a marble font, masterpieces by Giovanni della Robbia (1498). The cupboards were designed by Bernardo Buontalenti in 1593. The paintings on the wall are ascribed to Giorgio Vasari and some other contemporary Florentine painters. The large Gothic window with three mullions at the back wall dates from 1386 and was based on cartoons by Niccolò di Pietro Gerini.

|

|

|

|

The Green Cloister

|

|

Green Cloister, Paolo Uccello, The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden

|

Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) was a leading figure in establishing the Renaissance in Florence. He was a painter and a mathematician who was notable for his pioneering work on visual perspective in art. Paolo worked in the Late Gothic tradition, and emphasized colour and pageantry rather than the Classical realism that other artists were pioneering. In 1424 he painted episodes of the Creation and expulsion for the Green Cloister (Chiostro Verde) of Santa Maria Novella in Florence (now badly damaged), proving his artistic maturity.

Uccello's earliest known paintings, representing the creation of the animals and the creation of man, are part of a large outdoor fresco series in monochrome of Old Testament scenes in the Green Cloister of S. Maria Novella, Florence. The figures have a curvilinear rhythm and sculptural strength, and they are set in a decorative yet naturalistic environment of foliage withanimals, reflecting Ghiberti's influence and very like his Creation panel in the Gates of Paradise of the Florentine Baptistery. As the gates were designed in 1425 or later, Uccello's frescoes are usually thought to have been executed after his return fromVenice , but they may date from just before he went there and reflect other designs by Ghiberti, since a small copy of Uccello's lost St. Peter mosaic in Venice (1425) already seems to show his more mature Renaissance style.

Giotto used tonality to create form. Taddeo Gaddi in his nocturnal scene in the Baroncelli Chapel demonstrated how light could be used to create drama. Paolo Uccello, a hundred years later, experimented with the dramatic effect of light in some of his almost-monochrome frescoes. He did a number of these in terra verde or "green earth", enlivening his compositions with touches of vermilion. The terra verde (meaning green earth) technique is the use of green and brown earthy tones. The best known example of this technique is his equestrian portrait of John Hawkwood on the wall of Florence Cathedral.

The influence of Masaccio is seen in Uccello's scenes from the life of Noah.

|

| The Spanish Chapel

|

In the second half of the 14th century, Andrea di Bonaiuto painted the wonderful frescos for the adjacent Spanish Chapel, in which the picture of the Church of the Triumph of the Faith closely resembled Arnolfo di Cambio's design for the cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore. The spatial integrity of the building is already implicit in Arnolfo's plan of 1294. but the dome of the fresco model is augmented by Brunelleschi's octagonal drum that carries the dome. Another example of Dominican theology is Bonaiuto's fresco cycle showing Thomas Aquinas dominating the allegorical figures of all the liberal arts and the sciences of the theological cursus.

|

|

The Spanish Chapel, Cappellone degli Spagnoli , fresco by Andrea di Bonaiuto

|

The Spanish Chapel (or Cappellone degli Spagnoli) is the former chapterhouse of the monastery. It is situated at the north side of the green Cloister (Chiostro Verde). It was commissioned by Buonamico (Mico) Guidalotti as his funerary chapel. Construction started c. 1343 and was finished in 1355. The Guidalotti chapel was later called "Spanish Chapel", because Cosimo I assigned it to Eleonora of Toledo and her Spanish retinue. The Spanish Chapel contains a smaller Chapel of the Most Holy Sacrament. The Spanish Chapel was decorated from 1365 to 1367 by Andrea di Bonaiuto, also known as Andrea da Firenze. The large fresco on the right wall depicts the Allegory of the Active and Triumphant Church and of the Dominican order. It is especially interesting because in the background it shows a large pink building that may provide some insight into the original designs for the Duomo of Florence by Arnolfo di Cambio (before Brunelleschi's dome was built), although this interpretation is fantastical as the Duomo was never intended to be pink, nor to have the belltower at its back side. This fresco also contains portraits of pope Benedict IX, cardinal Friar Niccolò Albertini, count Guido di Poppi, Arnolfo di Cambio and the poet Petrarch. The frescoes on the other walls represent scenes from the lives of Christ and Saint Peter on the entry wall (mostly ruined due to the later installation of a choir), The Triumph of Saint Thomas Aquinas and the Allegory of Christian Learning on the left wall, and the large "Crucifixion with the Way to Calvalry and the Descent into Limbo" on the archway of the altar wall. The four-part vault contains scenes of Christ's resurrection, the navicella, the ascension, and Pentecost. The five-panelled Gothic polyptych that was probably originally made for the chapel's altar, depicting the Madonna Enthroned With and Child and Four Saints by Bernardo Daddi dates from 1344 and is currently on display in a small museum area accessed through glass doors from the far end of the cloister. Together, the complex iconography of the ceiling vault, walls, and altar combine to communicate the message of Dominicans as guides to salvation.

|

The Pharmacy of Santa Maria Novella is in Via della Scala, in the complex of Santa Maria Novella. It is no more a pharmacy, but a perfumery that still nowadays continues its commercial activity being open to the public. It is in a very monumental environment, with decorations and ancient pieces of furniture going back to various ages. It keeps also a valuable collections of scientific material, like thermometers, mortars, balances, measures, etc., besides to valuable pharmacy-pots from XV to XVIII century. It is documented that since the 1381 the Dominicans of Santa Maria Novella sold the roses water like a disinfectant, used especially during the epidemic periods. The friars cultivated th medicinal plants (the "Semplici" from the name of the Semplici Garden) in an adjacent garden, distilled herbs and flowers, prepared essences, elixirs, creams, balsams. In XVIII century its products were exported as far as Indies and China. In spite of the XVII-century abolitions, it remained working thanks to Fra Damiano Bensi and in 1866 was rented to the nephew Cesare Augusto Stefani, whose heirs manage still nowadays the activity. Today it is believed the most ancient pharmacy in all Europe, working since near 4 century, as well as one of the most ancient commercial stores in absolute. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Grotere kaart weergeven |

| |

Address | Piazza di Santa Maria Novella, 50123 Firenze (FI)

Opening hours | Open weekdays 9 a.m. - 5.30 p.m.

Fridays 11 a.m. - 5.30 p.m.

Saturdays 9 a.m. - 5 p.m.

Sundays and religious holidays 1 p.m. - 5 p.m.

The museum, adjacent to the church, is managed by the city of Florence and foresees a separate admission fee. The ticket includes a visit to the Green Cloister with frescoes by Paolo Uccello with scenes from the Old Testament and, being outside, are in bad shape but can still be admired.

The Chapter House, called the Cappellone degli Spagnoli or Spanish Chapel ever since it was used by the courtiers of Eleanor of Toledo, wife of Cosimo I. The chapel features frescoes by Andrea di Bonaiuto depicting Jesus Christ's passion, death and resurrection on the front wall as you enter. To the right, in the Triumph of the Doctrine, the dogs of God (a pun on the word Dominican - domini canes) are sent to round up lost sheep into the fold of the church. To the left, another fresco the Triumph of the Catholic Doctrine while the entrance wall frescoes depict stories of the life of St. Peter Martyr.

The tour ends in the ancient refectory where precious liturgical objects belonging to the church's sacristy are on display as well as a few recovered synopses from Orcagna's frescoes in the Tornabuoni chapel.

Santa Maria Novella | Opera per Santa Maria Novella | Guide to all the works of art

The Crucifix painted by Giotto, the wooden Crucifix sculpted by Brunelleschi and Masaccio’s Holy Trinity would suffice in themselves to establish the glory of the Church of Santa Maria Novella, and bear witness to the highest values of Western Christian civilization. However, the reality is somewhat otherwise since the church boasts many other works of art both in painting and sculpture and architecture, as evidenced by the beautiful facade designed by Leon Battista Alberti.

It is impossible to confine the breadth of works of art in this wonderful building within a specified art-historical period. Here the sense and weight of art constitute an extraordinary anthology, a wonderful overview not merely artistic, but also theological and philosophical, over the course of almost six centuries since its beginning. It is a story that was, and still remains, especially rich in facts, ideas and content, the receipt of which well-educated and well-prepared visitors are able to identify with a keen critical sense and with subtle intuition the charm and value of what was achieved here.

Santa Maria Novella | Interactive map

Francesca Flores D'Arcais, Giotto, Abbeville Press; 1st edition (October 1, 1995)

Ciatti, Marco / Seidel, Max (Hg.): Giotto. The Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella. München: Deutscher Kunstverlag 2004. Abb. 4° Br.

Firenze | Churches, cathedrals, basilicas and monasteries of Florence

Art in Tuscany | Domenico Ghirlandaio | The Tornabuoni Chapel

Walking in Tuscany | Florence | Santa Maria Novella

Bibliography

Damien Wigny, Au coeur de Florence : Itinéraires, monuments, lectures, 1990

[a] Alinari Firenze Piazza Santa Maria Novella c1854" by Leopoldo Alinari - Galerie Bassenge.

Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

[1] Tommaso Masaccio (c.1401-28) was an Italian 15th century Early Renaissance painter. Tommaso Cassai (full name Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Mone Cassai) is known to us by his nickname "Masaccio", which is a diminutive of "Tommasaccio", the Italian for something like "big ugly Tom".

Masaccio died at the early age of 26 or 27 but managed to paint a few pictures of such enormous impact as to affect not only the whole future course of Florentine painting but also that of European fine art painting in general. As a result, he ranks alongside the architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), the sculptor Donatello (1386-1466) and the architect and art theorist Leon Battista Alberti (1404-72) as one of the founding fathers of Renaissance art.

He was born at Castel San Giovanni, the modern San Giovanni Valdarno, located in the upper Arno valley, some 28 miles from Florence. Masaccio's father was a young notary, his mother, Mona Jacopa di Martinozzo, the daughter of an innkeeper from a nearby town.

Apart from what can be gleaned from his pictures, little extra is known of Masaccio's life. From documents it is known that in January 1422 he became a member of the Florentine painters' guild, the Arte de' Medici e Speziali, while living in the parish of San Niccolo Oltrarno. In 1424 he joined the Compagnia di San Luca, to which painters often belonged, while eight payments towards an altarpiece painted for the Carmelite church in Pisa attest to the fact that he was in that city during much of 1426, that he knew Donatello, and employed Andrea di Giusto. In 1427 Masaccio made a tax declaration to the newly instituted Catasta: he was then living in what is now the Via dei Servi and had his workshop near the Badia. This same source gives us the approximate date of his death: next to his name for the returns of 1429 is written, "Dicesi e morto a Roma", that is: "He is said to have died in Rome".

Nothing is known of Masaccio's art training. The apprentice system was such that he was probably learning a trade as early as 1410. This may have begun in a local painter's studio, or else in a family workshop. Or he may have been sent to train in a battega in Arezzo, in Florence, or elsewhere - but there is no evidence to show his early training was necessarily in the painter's craft.

Masaccio's earliest known surviving painting, an altarpiece of the Madanna and Child with Two Angels and Four Saints (1422; from S. Giovenale di Cascia, near S. Giovanni; now in the Uffizi, Florence) does give us some idea of what his training as a painter must have been. Masaccio was 20 years old when this picture was dated. It shows us that he is already interested in space: not only do the lines in the floor indicate an attempt to grasp the laws of linear perspective, but so does the structure of the throne, with its slanted sides and curved back. The sense of space is heightened both by the apparent modeling of the robes and faces and by the use of alternating light and dark colour in painting.

Wherever Masaccio trained, it can hardly have been in the strongly International Gothic atmosphere prevalent in Florentine painting in the first two decades of the 15th century, where a sinuous elegant surface line was more important than depth within the picture. On the contrary his interest in modeling, in flesh tones, in space, and in light is much more characteristic of Marchigian painters. Both Arcangelo di Cola da Camerino (fl.1416-22) and Gentile da Fabriano (c.1370-1427) show a keen interest in these things, and both were in Florence, the former about 1419-22, the latter first in 1419-20 and then again in 1422-5. It is possible that Masaccio was influenced by one or both of them. There is also one Florentine painter who shows much of Masaccio's interest in modeling and space, Giovanni Toscani, and it is conceivable that Masaccio was one of his pupils. Other possible masters to Masaccio were Bicci di Lorenzo and Francesco di Antonio. Masolino, who came from near San Giovanni, and with whom Masaccio worked on at least three commissions, was almost certainly not Masaccio's master: he may have hired Masaccio to help him with important commissions, but it was the much younger painter, Masaccio, who then influenced his senior.

The whole of Masaccio's authenticated extant work, besides the San Giovenale painting, derives from only five other commissions: the so-called "Matterza" Madonna and Child with St Anne (c.1424; Uffizi Gallery Florence); the Pisa Altarpiece (panels now dispersed); a fresco of The Trinity in S.Maria Novella, Florence; frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel, S.Maria del Carmine, Florence; and Saints Jerome and John the Baptist from an altarpiece originally in S.Maria Maggiore, Rome.

The first of these paintings, the Uffizi Madonna and Child with St Anne, was executed with the help of Masolino c.1424 for the church of S.Ambrogio in Florence. Masolino painted St Anne, plus all the angels except the middle one on the right; Masaccio did the Virgin, Christ Child, and remaining angel. In spite of the difference between Masolino's more orthodox approach and Masaccio's strong volumes, the picture is remarkably harmonious. Masaccio has placed his Madonna extremely low, emphasizing the light and shade falling on her knees, on the folds in her robes, and on the Infant Christ. As in the S.Giovenale painting, he has painted the Christ Child nude; but here the figure seems so solid and is so Classical in flavour that the painter must have drawn it after an antique statue. There are, in fact, many extant antique statues of babies in just this pose.

The chronology of the other known works is not clear, although they seem all to have been painted between 1425 and the artist's death, probably some time in 1428. It seems possible that Masaccio painted The Trinity in S.Maria Novella, Florence, in 1425 or 1426, perhaps for the feast of Corpus Domini in one of those years, although stylistically the painting is so advanced that it may well date after the painter's earliest work in the Brancacci chapel. Masaccio probably helped Masolino to plan the frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel in S.Maria del Carmine during 1425, and then began himself to paint there some time after Masolino's departure for Hungary in September of the same year. Masaccio must have worked at them during 1426, as well perhaps as during 1427. The Pisa Altarpiece is, as mentioned above, dated to the year 1426; while the panel of Saints Jerome and John the Baptist (National Gallery, London) from the S.Maria Maggiore altarpiece was probably painted during Masaccio's trip to Rome in 1427/28.

Masaccio's Themes | From the converging lines of the San Giovenale triptych, right through all his subsequent works, Masaccio developed two themes that were to remain central to the idiom of the Renaissance and to the history of Western painting. The first is the successful portrayal of a natural world within the painting, with convincing space, light, air, and objects. The second is part of this, but at the same time independent of it: the portrayal of a convincing replica of man, who dominates and gives order to that world. This is, of course, a visual version of the more general search for a correct scientific definition of man's place in the natural world, which occupies the Renaissance in all its facets.

Masaccio's Trinity terminates the Middle Ages by expressing the essence of medieval Christian belief in Renaissance terms. His work The Tribute Money in the Brancacci Chapel, on the other hand, stands clearly beyond the threshold, in the light-filled world of the Renaissance.

Nothing could be more traditional to the Christian age than Masaccio's Trinity theme of a predominant God the Father, supporting his crucified human Son, joined by the white dove of the Holy Spirit: the universal, the human, the spiritual. But nothing could be less traditional in its expression. Vaulted by a magnificent Renaissance triumphal arch, the divine trio appears almost suspended before a pierced wall. This coffered Brunelleschian space seems to be a mortuary chamber, a holy sepulchre from which the Christ is shown resurrected by His Father, Saviour to a waiting world, presented by the Virgin and St John; this world is symbolized by the two donors just outside. The worldly spectator is also included in the painting by association with the skeleton under the altar; unlike the human body of Christ, which rose intact, our worldly bodies decay. Above the skeleton are written some words to warn the passer-by; "I was that which you are, you will be that which I am". Inside the sepulchre, the space has been constructed according to the laws of linear perspective, so that the eye appears to be looking into the interior of a magnificent Renaissance building.

Masaccio set the background to The Tribute Money, in the Brancacci Chapel at S.Maria del Carmine, in a light-filled landscape, dominated (as is the countryside at San Giovanni Valdarno) by high hills. The painter, using newly established laws of perspective, created an infallible illusion of air, light, and space. But whereas in The Trinity God is the theme, here it is Man who dominates. Masaccio places in the natural scene classical statuesque figures, also apparently modelled after the Antique, who are above all human and free to move within their own natural world.

The Tribute Money emerges as, historically, the most important single picture in Florence today. Each individual in the painting stands, for the first time, strong and solitary, on a natural and benevolent earth, sustained by real air, bathed in light, master of the world stretching all around. Masaccio threw off the gloom and mystery of earlier times, resurrecting the forms of an ancient pre-Christian world. In the painting Christ stands equal to Man, not dominating him: a human being Himself, giving good advice to His followers. In The Tribute Money we already witness a Reformation - clearly evident too in the humanistic work of Donatello and Brunelleschi - in which Man does not cease to believe in Christ, although he may cease to believe in the infallibility of the Roman Church. Rather, Man ceases to believe in a triumphal Christ-God and begins to believe in a human Christ-Man.

Brancacci Chapel Frescos | The fresco paintings in the Brancacci chapel, of which The Tribute Money is one, relate scenes from the life of St Peter. The whole cycle seems to have been begun by Masolino about 1425, and then continued by Masaccio. The chapel was not actually finished until much later in the 15th century, by Filippino Lippi. The Tribute Money itself alludes in some way to Man's separate duties to the State and to the Church. In it St Peter is instructed by Christ to pay a tax to the civil authority. This must certainly be a reference to the obligations of the Roman Church towards secular authority; it probably also refers to each individual man's obligation to render separately to God and to Caesar that which is due to them.

The other paintings by Masaccio in the chapel seem to confirm this message: St Peter is seen preaching, baptizing, healing, and distributing alms: all corporal works of mercy. What then is the meaning of Masaccio's stupendous fresco of The Expulsion from Paradise on the entrance arch to the chapel? Perhaps Masaccio meant simply to point out that the anguish of Man over his loss of paradise can be solaced by the good works of Holy Mother the Church; the Church is the source of grace, through which Man can be saved.

The only two other extant, autograph works by Masaccio have already been mentioned: the various panels from the Pisa polyptych, and the panel of Saints Jerome and John the Baptist from Masolino's S.Maria Maggiore altarpiece. The former group includes the strongly rendered Madonna and Child with Four Angels, now in London's National Gallery, the central panel of the original altarpiece. Here, even within the most traditional late medieval schema, the painter introduces strong volumes for the Madonna's robes, and space all around the throne.

Above all else, he introduces the greatest innovation of Renaissance painting: light defined as coming from a single source, by the shadows it casts. In this painting too, one is aware of the great sensitivity and delicacy of the painter's brushwork - the angels playing lutes are of such simplicity and craftsmanship as to make them seem to sing. Two other remarkable paintings from this altarpiece are the small panels of the Crucifixion now in Naples (Museo e Gallerie Nazionali di Capodimonte), and the Nativity in Berlin (Staatliche Museum). In the former the animal-like figure of the crouched Magdalene gesturing towards the anguish of St John and of the Virgin is of such a simple expressive force as almost to defy analysis. Christ's stark, shadow-struck body, meant to be seen from below, is also intensely expressive. As for the small Nativity panel, its lifelike Kings, the animals, the Holy Family - all are bathed in a dawn light, clearly defining the spaces involved, throwing sharp shadows.

The London panel of Saints Jerome and John the Baptist was once part of a triptych painted on both sides for the Roman basilica of S.Maria Maggiore. This painting, which represents the founding of that church, flanked by saints, is predominantly by Masolino; for some unknown reason, however, Masaccio executed this one panel. Since Masaccio and Masolino worked together on the Uffizi Madonna, in the Brancacci Chapel, as well as perhaps in other places, it is not so surprising that they collaborated here too.

Artistic Legacy | Masaccio's contribution to the development of Western painting is enormous. During the first two decades of the 15th century, both sculpture (primarily through the work of Donatello) and architecture (through that of Brunelleschi) began to be cast in a new Renaissance idiom. In the course of a few years during the 1420s, Masaccio managed to set Western painting on a Renaissance course, similar in essence and language to that taken by those other expressions. If Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337) had created, over a century earlier, an ideal world in which Christian myths were acted out, Masaccio secularized that world by filling it with space, light, and air, and by placing a Classical sort of man within it, surrounded by nature. This idea of man as central to a logical natural world, and master of it, was to remain the principal source of imagery for Western painting until very recent times.

[2] At the north end of the transept of Santa Maria Novella two brothers who were heads of a very large and active workshop, Andrea di Cione (known as Orcagna) and Nardo di Cione provided the altarpiece and frescoes for the Strozzi Chapel, one of the most important decorative programs of the time.

Dominican commitment to orthodoxy, order, and the institutional church is evident on the left wall of the chapel where a Paradise shows the elect arranged row upon row, around and beneath the figures of the enthroned Divinity and the Virgin. Both figures are crowned; the figure of God even holds a sceptre. In this configuration the Virgin - or metaphorically Maria Ecclesia (the Church) - shares unmistakably the power of the Godhead on the model familiar from Roman thirteenth-century mosaics.

Nardo was brother of Andrea di Cione (called Orcagna) and of Jacopo di Cione. All attributions to Nardo are based on Ghiberti's statement that he painted some extant frescoes in the Strozzi Chapel in Sta Maria Novella, Florence.

[3] Rucellai family | While prominent in communal government and wealthy as cloth manufacturers from the late 13th century, the Rucellai did not play a part of real importance in Florentine politics, preferring, especially in the 15th century, to devote increasing time to study and the cultivated pleasures of private life. Giovanni (1403-81) built the Rucellai Palace from 1446. This was from a design by Alberti, as was another of Giovanni's commissions, the marble façade of S. Maria Novella. He was also a more perceptive patron of artists than either Cosimo or Lorenzo de' Medici. His Zibaldone (commonplace book) gives valuable insight into the reading and manner of life of the lettered merchants of the Quattrocento.

His son Bernardo (1448-1514), a trusted supporter of Lorenzo the Magnificent, wrote a history of Charles VIII's invasion of 1494-95, De bello italico, which makes precocious use of the term 'balance of power', and his grandson Giovanni (1475-1525), who entered the Church, has some reputation as a literary pioneer. He wrote free imitations of classical poems in the vernacular and one of the earliest classicizing tragedies, Rosamunda. It was Bernardo who laid out the gardens off the Via della Scala which became known as the Orti Oricellari (Rucellai Gardens). After his death his grandson Cosimo acted as host to discussions held there on philosophical, literary and political topics. Machiavelli took part in these and his Discourses were dedicated to Cosimo and to another habitué of the Orti, Zanobi Buondelmonti. Machiavelli set his dialogues in 'The art of war' there, with Cosimo as one of the protagonists.

[4] Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) | One of the most distinctive painters of the Early Renaissance, Florentine artist Paolo di Dono was nicknamed "Uccello" (bird) because of his paintings of birds and animals.

Younger than Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455), and Donatello (1386-1466), but older than Tommaso Masaccio (c.1401-28) and Piero della Francesca (1420-92), Uccello belonged to a generation of artists concerned with the general movement away from the flat decorative forms of the International Gothic style, towards naturalism. His work is characterized by an obsession with linear perspective, and a passion for clear colours and tapestry-like compositions. In his fine art painting, Uccello often creates a fairy-tale world of figures, animals and dramatic narrative.

We know that by 1407 Uccello was apprenticed to Lorenzo Ghiberti, in whose workshop he remained until 1415, when he joined the guild of painters, the Arte de' Medici e Speziali. But further details of Uccello's early activity and art training are not clear. From 1425 until 1431 it is believed he was busy creating mosaic art at St Mark's in Venice, and was therefore away from Florence during the period when Masaccio was creating the important frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel (1425-8; S.Maria del Carmine, Florence).

Uccello's rapid absorption of the new ideas in Renaissance art when he returned to Florence in 1431 is demonstrated by his fresco painting of Sir John Hawkwood, completed in 1436 on the wall of Florence Cathedral. The foreshortening and modeling give the trompe-l'oeil impression that the fresco of this English mercenary leader is a statue - the painting was indeed a substitute for the sculptural effigy originally planned. Uccello's painting of Four Prophets of 1443 round the clock face of the cathedral further extends his experiments towards seemingly three-dimensional pictorial space.

In about 1445 Uccello painted The Flood in the Green Cloister of S.Maria Novella in Florence; here modeling, architectural recession, and light and shadow play important parts. The Flood may be seen as a visual interpretation of the theories expounded by Alberti in his treatise Della Pittura (On Painting) of 1436. Alberti's two basic principles of art - beauty derived from geometry, and decorative form as ornament - are fully realized in this work. Uccello contrasts young, old, clothed, and naked figures, birds, and animals as though to satisfy Alberti's demands in Della Pittura for a copious and varied composition. Both the recession to one vanishing point, and the strange doughnut-shaped collar worn by one of the figures in the foreground are characteristic of Uccello's interest in geometrically constructed space.

The Battle of San Romano | Uccello's greatest work consists of three panels, painted c.1456, representing The Battle of San Romano (now in the National Gallery, London; the Uffizi, Florence; and the Louvre, Paris). The work was commissioned by Cosimo de' Medici, and doubtless gave great pleasure to his seven-year-old grandson, Lorenzo, for it is a bloodless but action-packed battle scene depicting the triumph of the Florentine army over that of Siena in 1432. On another level, it serves to mark the power of the Medici banking family in Florentine finance and politics. Uccello's work is a magical combination of scientific perspective and festive love of incident and action. Broken lances serve both to suggest the melee of battle, and to act as perspective lines to lead the eye inward towards the horizon. In the London panel, a foreshortened, fallen knight and curved armour form part of the perspectival checkerboard of events. Uccelo has neatly dovetailed the new linear perspective with existing rules relating to the visual impression that warm colours (like red) jump forward, and cold colours (like blue or green) recede.

Other Masterpieces St George and the Dragon (c.1455-60; National Gallery, London) uses similar, but less obvious, perspective tricks; the profiled princess still retains an elongated, Gothic quality. The painting is on canvas, rather than the more usual panel, indicating a change in taste: it is a portable possession of beauty, rather than a fixed devotional object. A Hunt in a Forest (1468; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford), possibly Uccello's last work, is a veritable carnival in paint showing a hunting party. The movement of the animals is stylized, with their front legs raised and their back legs on the ground. This is a repetition of the formula used for the horses in The Rout of San Romano and St George and the Dragon paintings, and perfectly suggests their springiness.

Uccello's lasting achievement was his ability to overlay basic Quattrocento geometric structure with poetic detail, although the underlying logic is always visible.

|

Podere Santa Pia, with its wide panoramic terrace overlooking the Maremma, is the ideal place to enjoy the beauty of Tuscany and to pass a very relaxing holiday in contemplation of nature, with the advantage of tasting the most typical dishes of Tuscan cuisine and its best wines.

The extreme simplicity of Tuscan cuisine is its strongest strength, as the flavours that emerge during the cooking process are vibrant and pure. A little known fact about Tuscan cuisine is that the French learned how to cook from their Tuscan counterparts when it was imported by Catherine de' Medici into the court of Henry II. The Tuscan style of cooking is richly flavoured and wholesome. With its original kitchen and the wood burning pizza oven, Casa Santa Pia offers an upbeat atmosphere. Enjoy an alfresco lunch on the terrace overlooking the vineyards and olive trees of southern Tuscany...

Tuscan Holiday houses | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

Podere Santa Pia, with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montecristo

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden |

|

Montecristo, view from Santa Pia

|

| |

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Santa Maria Novella, the Cappella Tornabuoni

|

The Piazza of Santa Maria Novella

In 1287, with a decreto of the Florentine Republic, Piazza of Santa Maria Novella was to be created and given to the Dominicans for decoro, or decorum and ornament, to the new church being built. Right away, the piazza became theater to festivals, tournaments and other contests. The two obelisks of marble from Serravezza, each one sitting atop four bronze turtles by Giambologna and topped with a Florentine lily, were the "goals" for the "Palio dei Cocchi".

On the side opposite the church, the Loggia of the San Paolo hospital was built at the beginning of the 13th century. In the second half of the 15th century, the hospital was enlarged and given the loggia with stone columns.

From Piazza del Signoria to the Mercato Centrale

The arches between each column have round glazed terracotta reliefs of saints by Andrea della Robbia. The lunette shaped relief of The Embrace between St. Dominque and St. Francis over the right portal is also by Andrea della Robbia.

Where Piazza del Duomo is Florence’s religious focus, (1) Piazza della Signoria forms its civic heart. For centuries the city was run from the (2) Palazzo Vecchio in this piazza, a rambling palace filled with spectacular salons and precious works of art.

Take in the statues beneath the 14th-century (3) Loggia dei Lanzi on the piazza’s southern flank, notably Donatello’s “Judith and Holofernes.” Then follow Via Vacchereccia from the square’s southwest corner to the (4) Mercato Nuovo at the corner with Via Por Santa Maria, a small, loggia-shaded market that dates from the 11th century.

From the market walk west to visit the (5) Palazzo Davanzati, on Via Porta Rossa on the corner of Via de’ Sassetti—it is one of Florence’s most enchanting museums. The interior preserves the appearance, furniture, and fittings of a medieval Florentine town house.

Either continue west from here, or backtrack a little to pick up one of the small alleys south off Via Porta Rossa to Via delle Terme and then Borgo Santi Apostoli. Both these streets are quieter and more appealing to explore than Via Porta Rossa.

All three streets west eventually bring you to (6) Santa Trinità in Piazza Santa Trinità, a church bypassed by most visitors. Step inside to admire the many frescoes, especially those of Domenico Ghirlandaio in the Cappella Sassetti (1482-85).

Then take Via del Parione to the west of the church, looking out for the tiny alley (first right) that takes you to Via del Purgatorio, where you should turn left to (7) Palazzo Rucellai, on Via della Vigna Nuova opposite Via del Purgatorio. The latter dates from the 1440s and is known for its restrained classical facade.

Turn right (east) down Via della Vigna Nuova to Via de’ Tornabuoni, two streets with the lion’s share of Florence’s designer stores. Either explore the smart boutiques here or turn immediately left on Via della Spada and then right on Via delle Belle Donne to Piazza Santa Maria della Novella.

The piazza is home to (8) Santa Maria della Novella, the city’s most compelling church (www.smn.it) after Santa Croce. Amid countless artistic highlights, the key treasures are Masaccio’s painting of the “La Trinità” (1427) and the fresco series in the chancel and its flanking chapels.

Follow Via dei Banchi from the east side of the piazza and take the first alley on the left, crossing Via dei Panzani and following Via del Giglio to the entrance to the (9) Cappelle Medicee in Piazza Maria Madonna degli Aldobrandini. This complex of crypts and chapels contains the tombs of many members of the Medici dynasty, but is best known for several major sculptures by Michelangelo, created to adorn the tombs of the family’s more notable members.

One block north of the chapels, off Via Del Ariento, is the (10) Mercato Centrale, or central market, a fantastic medley of color and activity, crammed with fruit, vegetables, meat, cheese, herbs, pasta, and seasonal specialties such as truffles, wild boar, and plump porcini mushrooms.

|

|

|

National Geographic | www.nationalgeographic.com/florence-walking-tour-3

Florence | Transport |

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()