| |

|

Much of Giotto's biography and artistic development must be deduced from the evidence of surviving works (a large portion of which cannot be attributed to him with certainty) and stories that originate for the most part from the late 14th century on.

Vasari, the historian of Florence, tells the touching story of how the renowned Cimabue, strolling out into the country, came upon the youngster scraping upon a rock the outlines of one of the sheep which he had been set to watch, and how the master had been so delighted with the boy's talent that he had immediately arranged to bring him to Florence as his pupil. But more accurate historians, with no cause to be overpatriotic for beloved Florence, have rejected this story as fable. In view of the innovations in painting effected by Giotto and his completely different point of view, it seems more reasonable to suppose that his talents were unspoiled by his celebrated predecessor.

Born in 1267, Giotto must have been active before the last decade of thirteenth century. The date of Giotto's birth can be taken as either 1266/67 or 1276, and the 10 years' difference is of fundamental importance in assessing his early developmentand is crucial to the problem of the attribution of the frescoes in the Church of San Francesco, in Assisi, which, if indeed by Giotto, are his great early works. It is known that Giotto died on Jan. 8, 1337 (1336, Old Style); this was recorded at the time in the Villani chronicle.[2]

Giotto has always been assumed to have been the pupil of Cimabue.Two independent traditions, each differing on the particular circumstances, assert this, and it is probably correct. Furthermore, Cimabue's style was, in certain respects, so similar to Giotto's in intention that a connection seems inescapable. Cimabue was the most outstanding painter in Italy at the end of the 13th century.

it seems almost certain that Giotto began his remarkable development with Cimabue, inspired by his strength of drawing and his ability to incorporate dramatic tension into his works. On the other hand, whatever Giotto may have learned from Cimabue, it is clear that, even more than the sculptor Nicola Pisano about 30 years earlier, he succeeded in an astonishing innovation that originated in his own genius—a true revival of classical ideals and an expression in art of the new humanity that St. Francis had in the early 13th century brought to religion.

Giotto is regarded as the founder of the central tradition of Western painting because his work broke free from the stylizations of Byzantine art, introducing new ideals of naturalism and creating a convincing sense of pictorial space. His momentous achievement was recognized by his contemporaries. "He converted the art of painting from Greek to Latin and brought in the modern era" - this is Cennino Cennini's synthesis fifty years after Giotto's death, underscoring the revolutionary character of Giotto's painting, and Dante praised him in a famous passage of The Divine Comedy, where he said he had surpassed his master Cimabue.' The late-16th century biographer Giorgio Vasari says of him: "[H]e made a decisive break with the crude traditional Byzantine style, and brought to life the great art of painting as we know it today, introducing the technique of drawing accurately from life, which had been neglected for more than two hundred years."[2]

The decoration of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (between 1303-1305) has been universally recognized as the most significant and most paradigmatic creation of Giotto and one of the capital events in the history of the European painting. If we look at the contents of his artistic revolution, we have to agree that the first manifestations are present in the decoration of the Assisi Upper Basilica.

Completed in 1305 for the Enrico Scrovegni family in Padua, Italy, the frescoes adorning the walls and ceiling of the chapel relate a complex, emotional narrative on the lives of Mary and Jesus.

Dividing his time between his job as chief architect of the Duomo of Florence (the design of the belltower belongs to Giotto) and the many prestigious commissions (the Peruzzi Chapel, the Bardi Chapel (after 1317) also illustrate Giotto's radical innovations.

|

Cappella degli Scrovegni all'Arena, Padua

|

|

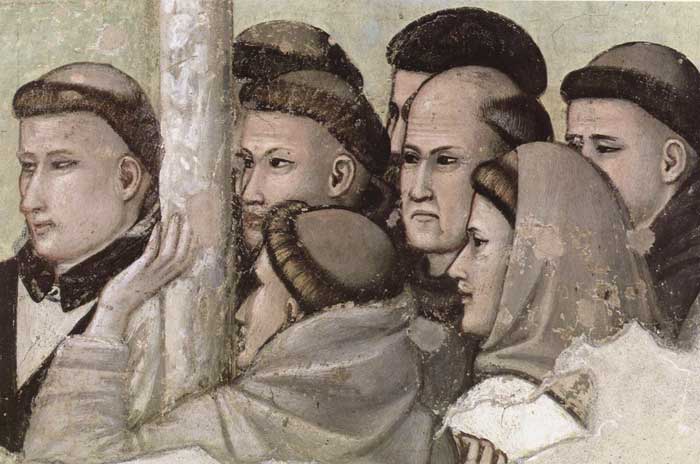

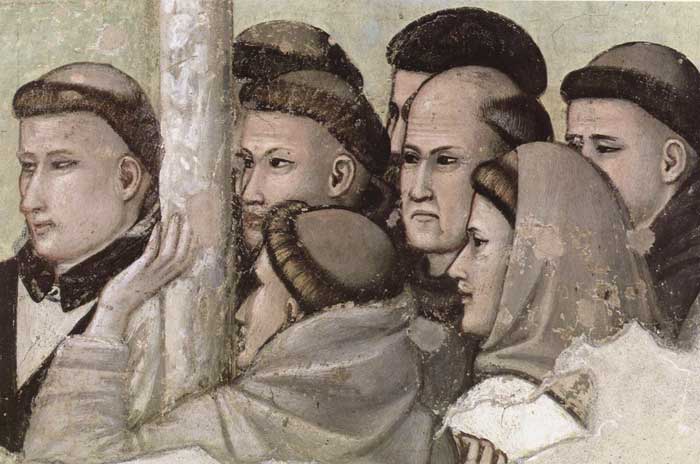

Giotto di Bondone, Scenes from the Life of Christ, Resurrection (detail), Cappella degli Scrovegni all'Arena, Padua

|

The decoration of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (between 1303-1305) has been universally recognized as the most significant and most paradigmatic creation of Giotto and one of the capital events in the history of the European painting. If we look at the contents of his artistic revolution, we have to agree that the first manifestations are present in the decoration of the Assisi Upper Basilica.

It is very probable that Giotto has worked in Assisi about ten years earlier than in Padua, that is to say, around 1290 or a little later.

The concept of space formulated for the first time in Assisi was already known to the ancient Greeks and Romans, but had been lost in Medieval times. This is not just a new way of painting. The idea of an illusionary reconstruction of a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface also implies that the reality perceived through one's senses acquires a new artistic meaning.

Dividing his time between his job as chief architect of the Duomo of Florence (the design of the belltower belongs to Giotto) and the many prestigious commissions (the Peruzzi Chapel, the Bardi Chapel (after 1317) also illustrate Giotto's radical innovations.

Giotto di Bondone |

Scrovegni Chapel

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Lamentation, 1164

|

|

Giotto, Scenes from the Life of Christ, Lamentation (The Mourning of Christ), 1304-06, Cappella Scrovegni (Arena Chapel), Padua

|

One of Giotto's frescos from his series on the life and passion of Jesus, in the Arena Chapel in Padua.

After his death Jesus is mourned over by a small group of followers, among whom his mother. After that, they lay him in his grave. With varied gestures, indicating individual degrees of sorrow, the women and John approach the body of Christ. Their gestures seem to pave the way for the most intense impression of grief, the embrace and gaze of the mother. At the same time, the gestures of the women and of the disciples, which are reflected once more by the angels, appear like a development of the mother's sorrow, which is concentrated on the moment of the most intimate encounter.

|

A comparison between two paintings of th e same subject (by Giotto and the Master of Nerezi) may clarify the novelty represented by the paintings of Giotto and justify the importance of his contribution to the Early Renaissance.

The first painting is by an anonymous Byzantine artist, referred to as the Master of Nerezi: a fresco on the Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the Church of St. Pantaleimon, created in 1164 (Middle Byzantine period) located in Nerezi, Macedonia. The other represents the same subject as depicted by Giotto in 1304-1306, in the Capella degli Scrovegni, in Padua, Italy.

The influence of Byzantine art in western Europe, particularly Italy was seen in ecclesiastical architecture, through the development of the Romanesque style in the 10th century and 11th centuries. The Master of Nerezi is undeniably able to transmit something of the pathos, the emotional dimension, of his subject, within the constraints of the Byzantine formal rules. In comparison to the early, strictly hieratic and solemn expression of the royal or Imperial-Christian art of Byzantium, there is here a more dynamic visual concept and action indeed: The Virgin Mary embracing the deposed Christ, the curved body of the disciple holding the hand of Christ, within a very briefly indicated location and schematic spatial setting.

As Gombrich (The Story of Art) observed about the Byzantine style, within this basically two-dimensional formal concept in painting, we distinguish also the heritage of Greek and Hellenistic art, largely transformed but still recognizable. For example: skiagraphia, or “shadow painting”, was a system of tonal and color modulation employing mainly, according to some specialists, graphic elements such as cross-hatching. Its initial development was attributed to the Athenian painter Apollodorus (430-400 BCE). Skiagraphia aimed at optical effects, the creation the impression of solid and round bodies in space taking into account a subjective point of view. It survives in Byzantine painting as a conventionalized linear system of “patterned” anatomical representation.

In contrast to the Pieta by the Master of Nerezi, Giotto’s figures are solidly articulated in themselves and among each other within a unified and coherent spatial setting. They not simply rest as patterns upon a surface, but occupy their own space and interact within the virtual space of the painted setting: the pictorially constructed box or stage. Two are the main sources, according to Gombrich, of Giotto’s accomplishment: classic (Roman) sculpture and the Christian plays publicly staged on different occasions in front of the churches, the theater as a traditional instrument of mass education and indoctrination in the Christian Church. In Giotto's Lamentation we recognize a tableau vivant or "staged picture" of representations of sacred narratives.

Art in Tuscany | Byzantine Art

|

|

Lamentation (Pieta) by the Master of Nerezi, 1164

Lamentation by Giotto, 1304-06

|

Roman period

Three principal works are attributed to Giotto in Rome. They are the great mosaic of Christ Walking on the Water (the “Navicella”), over the entrance to St. Peter's; the altarpiece painted for Cardinal Stefaneschi (Vatican Museum); and the fresco fragment of “Boniface VIII Proclaiming the Jubilee,” in San Giovanni in Laterano (St. John Lateran). Giotto is also known to have painted some frescoes in the choir of old St. Peter's, but these are lost.

These Roman works also pose problems in attribution and criticism. The attribution of the “Navicella” is certain; it is known that Cardinal Stefaneschi commissioned Giotto to doit. The mosaic, however, was almost entirely remade in the 17th century except for two fragmentary heads of angels, so that old copies must be used for all stylistic deductions. The fresco fragment in San Giovanni in Laterano was cleaned in the 20th century and was tentatively reattributed to Giotto on the basis of its likeness to the Assisi frescoes, but the original attribution can be traced only as far back as the 17thcentury. The “Stefaneschi Altarpiece,” with its portrait of the Cardinal himself, must be one of the works commissioned by him. The fact that he commissioned Giotto to do the “Navicella” might suggest that this work is by Giotto as well, but the altarpiece is so poor in quality that it cannot be by Giotto's own hand. It may be observed that several works bearing Giotto's signature, notably the “St. Francis of Assisi” (Louvre, Paris) and the altarpieces in Bologna and Florence (Santa Croce), are generally regarded as school pieces bearing his trademark, whereas the “Ognissanti Madonna,” unsigned and virtually undocumented, is so superlative in quality that it is accepted as entirely by his hand.

During this period Giotto may also have done the Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella and the “Madonna” in San Giorgio e Massimiliano dello Spirito Santo (both in Florence). These works may be possibly identifiable with works mentioned in very early sources, and if so they throw light on Giotto's early style (before 1300). It is also possible that, about 1305, Giotto went to Avignon, in France, but the evidence for this is slender.

|

|

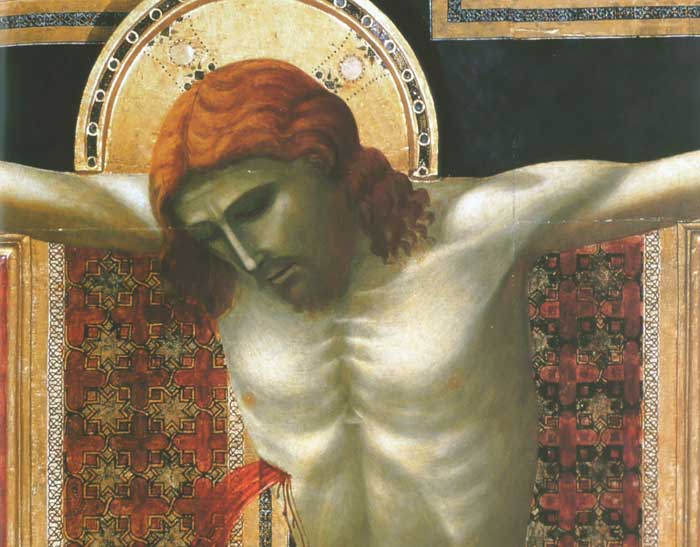

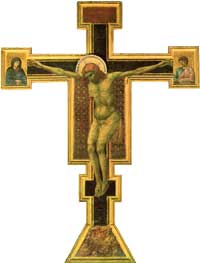

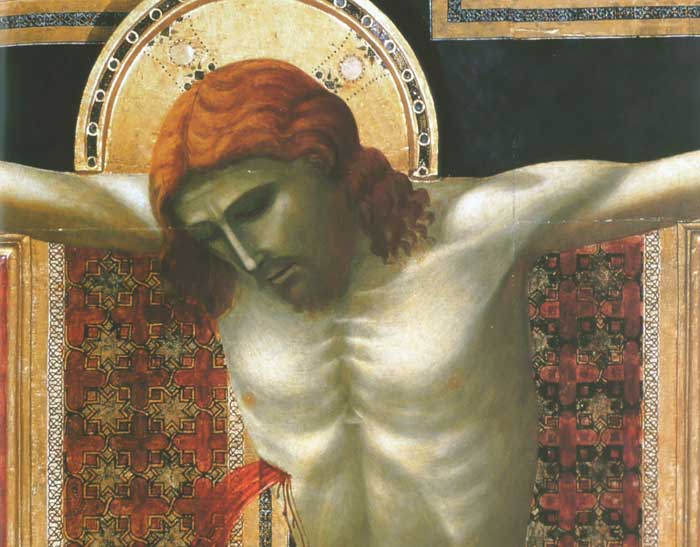

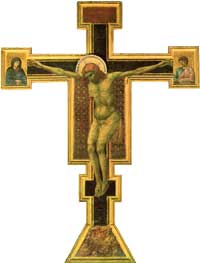

Giotto di Bondone, Crucifix (detail), about 1290-1300, gold and tempera on panel, 578 x 406 cm, Firenze, Santa Maria Novella

|

| In contrast to earlier representations of Christ on the Cross, such as those by his teacher Cimabue, Giotto emphasizes the earthly heaviness of the body: the head sinks deeply forward and the almost plump body sags. The human side of the Son of God is made clear. Mary and John look down sorrowfully from the horizontal ends of the cross at the dead Lord.

This, probably Giotto's earliest surviving work, is the largest and most ambitious of the shaped panels of Christ on the cross painted by Giotto. Although his limited anatomical knowledge prevented him attaining the realism of his later crucifixes (In Padua and Rimini), Giotto's break with Byzantine tradition is clear. This can be seen from the natural pose, the sense of real weight in the way Christ's body so painfully hangs, the basic simplicity of the loin-cloth, and the realism of the two feet fixed with a single nail.

Art in Tuscany | Santa Maria Novella | The Crucifix by Giotto |

|

|

| |

|

|

At the end of the thirteenth and during the first years of the fourteenth century, a debate was going on in religious and theological circles between those who emphasized Christ's humanity, favored images of his suffering and death, and those — especially the Dominicans — who wanted to return to the more ancient theological tradition that emphasized the divinity of Christ and thus favored images of glory. For the latter group, death and the cross signify not only the moment of suffering, but the concept of resurrection. Giotto's panel, not by chance executed for a Dominican convent, is connected with this new theological and spiritual movement, and reveals a seldom noticed aspect of Giotto's personality. Even in his first works, and then throughout his long and finely articulated artistic career, he was an attentive and sensitive interpreter of the most gripping theological and spiritual problems of his day [5].

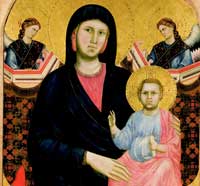

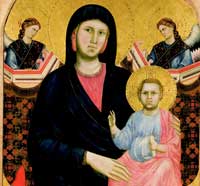

In the painting, the Virgin Mary is sitting on a marble throne. The painting has a three-dimensional feel. Here, Giotto distances himself from the Byzantine style of painting which characterized art in those years. Indeed, the Virgin Mary is wearing the traditional red cap, but a few locks of hair are falling onto her shoulders. The gold engraved decorations are of particular relevance: some say this aspect was inspired by a mix of both Arabic writings and the French gothic style. Giotto’s early style is evident in this work, and can be linked to his frescos in Assisi, the Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella and the fragment in Borgo San Lorenzo. The date of its execution, therefore, cannot be far from the date of the frescos in Assisi. Many believe it was completed in the late-1200s.

Art in Tuscany | Giotto, Madonna of San Giorgio alla Costa

|

|

Giotto, Madonna and Child, 1295-1300, tempera on wood, 180 x 90 cm, San Giorgio alla Costa, Florence |

Madonna Enthroned, also known as the Ognissanti Madonna, is a painting by the Italian late medieval artist Giotto di Bondone, housed in the Uffizi Gallery of Florence. It is generally dated to around 1310. The panel from 1306-10, ca. was originally placed on the old partition wall of the church of Ognissanti, officiated by the Umiliati friars before it was moved to their convent, at least by the end of the 17th century. In 1810, following the French suppression of convents, it was placed in the Accademia. It has been in the Uffizi since 1919.

The painting has a traditional Christian subject, representing the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child seated on her lap, with saints surrounding the two. It is celebrated often as the first painting of the Renaissance, due to its newfound naturalism and escape from the constraints of Gothic art.

Art in Tuscany | Giotto di Bondone | Ognissanti Madonna (Madonna in Maestà)

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Giotto Di Bondone | The Massacre of the Innocents 1310s

|

|

Giotto Di Bondone | The Massacre of the Innocents, fresco at Assisi

|

Frescoes on the ceiling of the north transept of the Lower Church in Assisi.

A new decoration of the lower church in Assisi was undertaken connected to the first centenary of the death of St Francis. Franciscan authors attribute the fresco cycle on the ceiling of the north transept to Giotto. However, this attribution is not accepted by the majority of critics, they are thought to have been executed by collaborators and followers.

The fresco cycle on one side consists of large scenes from the life of the Virgin and the childhood of Christ separated by decorative bands with busts of Prophets, while the other side represents scenes from the Passion of Christ. The west wall is occupied by scenes representing the Miracle of St Francis in Sessa (in two parts) and the Annunciation.

Giotto's impressionistic technique seems to show the angels in flight

Giotto's revolutionary style influenced later painters - those infants' bodies look forward to Mantegna and Picasso.

|

The Santa Croce Chapels | The Bardi Chapel and the Peruzzi Chapel in Santa Croce, Florence

|

|

Giotto, Vision of the Ascension of St Francis(detail), c. 1325, fresco, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

|

At the end of 1313, Giotto was back in Florence and was once more working in a Franciscan church, in the great Minorite church of Santa Croce, for which he was to continue creating works right up until the end of his life. According to a statement made by the Florentine artist Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378—1455), Giotto painted four of the chapels here. Several noble Florentine families are also said to have commissioned panel paintings from him, with which they endowed the altars in Santa Croce. But only two chapels and one altarpiece which can confidently be attributed to Giotto have survived the ravages of time - the Peruzzi and Bardi chapels.

The two chapels, which Giotto decorated for the two Florentine banking dynasties, lies next to one another in the Franciscan church. On the left, we can see into the Bardi Chapel and can make out the vault with its representations of the Franciscan virtues; to the right, in the Peruzzi chapel we can see the scenes from the life of St John the Evangelist. It is clear that Giotto composed these latter paintings in relation to the view from outside the chapel. Giotto painted a fresco of the Stigmatization of St Francis on the outside wall of the Bardi Chapel over the arch, which identifies the dedication of the chapel from a distance and at the same time provides the Franciscans with a large-scale image within the church itself of a defining moment in the life of their patron and founder.

The Bardi family of Florence founded one of Europe's first international banks in the 12th century. In addition to making loans to nobles, they also collected taxes and financed various manufacturing activities in Florence, especially wool processing. The Bardi bank opened branches in other places including England, and made large loans to Edward III for his wars against Scotland and France. That led to the failure of the Bardi bank in 1344 when Edward defaulted on his obligations.

Art in Tuscany | Giotto di Bondone | The Bardi Chapel and the Peruzzi Chapel in Santa Croce, Florence

|

|

The Bardi Chapel and the Peruzzi Chapel The Bardi Chapel and the Peruzzi Chapel

in Santa Croce, Florence

|

'At first glance the small painting of The Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple looks like a self-contained object. It has a balanced composition: two pairs of standing figures flank a dainty ciborium that symbolizes the Temple of Jerusalem. Following the gospel of Luke, the artist has illustrated the dramatic moment when Simeon and the prophetess Anna recognize the Christ Child as the savior.

Ever since the early nineteenth century, the Presentation has been known to be one of a series of seven paintings of the life of Christ (the others are in Munich, London, and New York). Although some scholars have questioned the traditional attribution of the series to Giotto, all the scenes are devised with such imagination and executed with such depth of feeling that only he could have painted them. There is nothing stereotyped about the compositions: each action is expressive, each face is individual. Thus, in the Presentation, the child struggles to get back in his mother’s arms. None of Giotto’s followers made such telling observations of human behavior.'

Source: Everett Fahy (1978), "The Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple," in Eye of the Beholder, edited by Alan Chong et al. (Boston: ISGM and Beacon Press, 2003): 39.

See also Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, The Presentation of the Christ Child in the Temple

|

|

The Presentation of the Christ Child, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

The Presentation of the Christ Child, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston |

[1] This painting, formerly attributed to Paolo Uccello, portrays five famous men, Giotto (representing painting), Uccello (representing the principles of perspective and animal painting), Donatello (representing sculpture), Manetti (representing mathematics), and Brunelleschi (representing architecture). The work is belived to be begun by Uccello, but finished later by another painter.

Paolo Uccello (1397 - 1475) was a painter (and also a creator of mosaics) in the employ and patronage of the powerful Florentine Renaissance family, the House of Medicis. Paolo Ucello is considered the father of the art of the perspective. Ucello worked in the Late Gothic tradition, and emphasized color and pageantry rather than the Classical realism that other artists were pioneering. His style is best described as idiosyncratic, and he left no school of followers. He had some influence on twentieth century art and literary criticism.

[2] About 1373, a rhymed version of the Villani chronicle was produced by Antonio Pucci, town crier of Florence and amateur poet, in which it is stated that Giotto was 70 when he died. This fact would imply that he was born in 1266/67, and it is clear that there was 14th-century authority for the statement (possibly Giotto's original tombstone, now lost). But Giorgio Vasari, in his important biography (1550) of Giotto, gives 1276 as the year of Giotto's birth, and it may be that he was copying one of the two known versions of the Libro di Antonio Billi, a 16th-century collection of notes on Florentine artists. In the Codex Petrei version, a statement that Giotto was born in 1276 at Vespignano, the son of a peasant, occurs at the very end of the “Life” and may have been added much later, even, conceivably, from Vasari. In any case, whether Vasari or “Antonio Billi” first made the statement, it cannot have the same authority as that attached to Antonio Pucci, who was about 27 when Giotto died. Certainty of the date of Giotto's birth, if settled by new documents, could help to solve the problem of his work at Assisi, as well as the question of the origins of his style.

[3] Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, trans. George Bull, 1965, London,Penguin Classics.

Since the Renaissance, Giotto has been credited with reviving the illusionistic painting of antiquity through his use of light, shadow, and perspective to imitate natural appearances. According to the Florentine writer Filarete, Giotto surreptitiously painted flies on a figure in such a convincing manner that his master Cimabue tried to brush them away. The painting does not survive, and may never have existed. This anecdote may simply have been a rhetorical metaphor for artistic excellence, modelled on the ancient stories of Zeuxis' grapes and Parrhasios' curtain. The story of Giotto's flies, already in circulation when told by Filarete in the 1460s, was repeated by the early art historians Giorgio Vasari in 1550 and Karl van Mander in 1604, and alluded to by numerous artists in their paintings.

[4] In 2010 Anna-Marie Hilling, a British art restorer uncovers a lost Giotto masterpiece, The Ognissanti Crucifix.

The Ognissanti Crucifix was a neglected Italian treasure which a team of experts have now repaired and identified. After cleaning the work painstakingly over several years, whenever funding allowed, Hilling and the other four members of the paint restoration team found strong evidence to suggest the crucifix was a genuine Giotto. Further studies, including infrared photography and X-rays, conducted last year inside the Florentine laboratory Opificio delle Pietre Dure, unearthed clear proof. Visible beneath the paintwork were preparatory sketches which allowed Giotto specialists to attribute the work as the 14th-century artist's own. It is now thought the crucifix must have been painted around 20 years after Giotto finished his other well-known monumental crucifix in Florence's Santa Maria Novella church.

The restoration of Giotto's Ognissanti Crucifix was started by Paola Bracco in 2002. The majestic tempera on panel realised by Giotto and his workshop around 1310-1320 had been sadly neglected for centuries. Kept in the sacristy of the church of Ognissanti, it was rarely seen and the vigorous modelling of the flesh tones of the figures, and the many precious details of the pictorial surface, were hidden by a severely altered layer due to a treatment of the past and century-old grime.

Anna-Marie Hilling, painting restorer, has lived in Florence since 1986.

[5] Francesca Flores D'Arcais, Giotto, Abbeville Press, (October 1, 1995), New York, London, Paris, pp. 105-107.

|

Francesca Flores D'Arcais, Giotto, Abbeville Press; 1st edition (October 1, 1995)

Giotto (1266-1337) is considered one of the founders of modern painting, having broken away from the rigid, stereotyped figures of Byzantine and medieval art to give his characters natural expression and solid three-dimensionality. D'Arcais leads readers on a chronological survey of Giotto's life and works.

Ciatti, Marco / Seidel, Max (Hg.): Giotto. The Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella. München: Deutscher Kunstverlag 2004. Abb. 4° Br.

Art in Tuscany | Italian Renaissance painting

Art in Tuscany | Giotto di Bondone |

Scrovegni Chapel

Stubblebine, James (ed.), Giotto: The Arena Chapel Frescoes, New York, 1969.

Basile, Giuseppe. Giotto: The Arena Chapel Frescoes, London, 1993.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Giotto and his works in Padua, by John Ruskin

Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects | Giotto

|

|

|