Source: Opera per Santa Maria Novella |Piazza S. Maria Novella 18 - 50123 Firenze

Santa Maria Novella | Opera per Santa Maria Novella | Guide to all the works of art

The Crucifix painted by Giotto, the wooden Crucifix sculpted by Brunelleschi and Masaccio’s Holy Trinity would suffice in themselves to establish the glory of the Church of Santa Maria Novella, and bear witness to the highest values of Western Christian civilization. However, the reality is somewhat otherwise since the church boasts many other works of art both in painting and sculpture and architecture, as evidenced by the beautiful facade designed by Leon Battista Alberti.

It is impossible to confine the breadth of works of art in this wonderful building within a specified art-historical period. Here the sense and weight of art constitute an extraordinary anthology, a wonderful overview not merely artistic, but also theological and philosophical, over the course of almost six centuries since its beginning. It is a story that was, and still remains, especially rich in facts, ideas and content, the receipt of which well-educated and well-prepared visitors are able to identify with a keen critical sense and with subtle intuition the charm and value of what was achieved here.

Santa Maria Novella | Interactive map

Art in Tuscany | The church of Santa Maria Novella

Marco Ciatti, Max Seidel, Giotto: The Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella, Deutscher Kunstverlag (April 1, 2005)

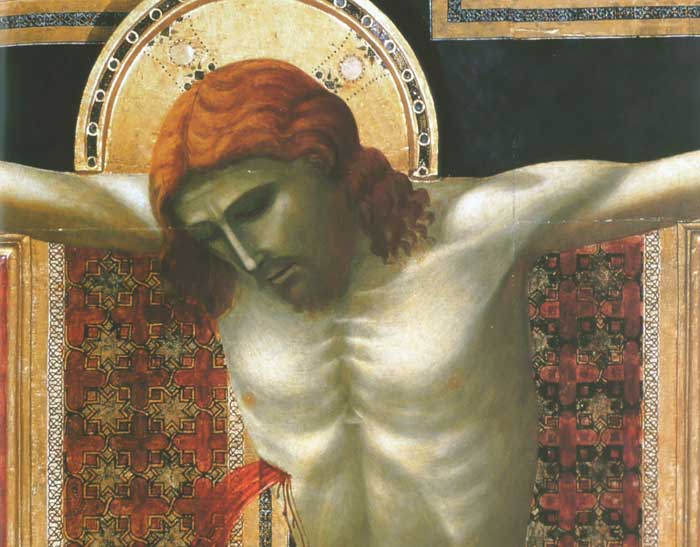

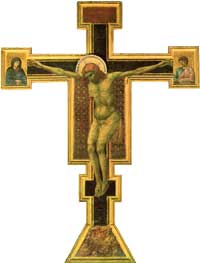

[1] The authorship of a large number of panel paintings ascribed to Giotto by Vasari, among others, is as broadly disputed as the Assisi frescoes. According to Vasari, Giotto's earliest works were for the Dominicans at Santa Maria Novella. These include a fresco of the Annunciation and the enormous suspended Crucifix, which is about 5 metres high. It has been dated around 1290 and is therefore contemporary with the Assisi frescoes.

Giotto di Bondone was a Florentine painter and architect. He was already recognized by Dante as the leading artist of his day. His significance to the Renaissance can be gauged from the fact that not only the leaders in the early 15th-century transformation of the arts, such as Masaccio, but the key figures of the High Renaissance, such as Raphael and Michelangelo - one of whose early studies of Giotto's frescoes in the Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce, has survived - were still learning from him and partly founding their style on his example. The reasons for this are twofold. Firstly, his art is notable for its clear, grave, simple solutions to the basic problems of the representation of space and of the volume, structure, and solidity of 3-dimensional forms, and above all of the human figure. Secondly, he was a genius at getting to the heart of whatever episode from sacred history he was representing, at cutting it down to its essential, dramatic core, and at finding the compositional means to express its innermost spiritual meaning and its psychological effects in terms of simple areas of paint. His solutions to many of the problems of dramatic narrative were fundamental. They have subsequently been elaborated on in many ways, but they have never been surpassed.

Part of the secret of Giotto's success in the representation of the fundamentals of human form and human spiritual and psychological reaction to events was his close attention to, and deep understanding of, the achievements of the sculptors Nicola Pisano, Arnolfo di Cambio and, above all, Giovanni Pisano, who were tackling the same basic representational problems in a naturally 3-dimensional medium. The essential unity of the arts in Giotto's day is even more dramatically illustrated by the fact that in the last years of his life he was assigned the major architectural commission in Florence, namely the building of the Campanile ('Giotto's Tower') of the cathedral (1344). The fact that it would almost certainly have fallen down if his successor, Andrea Pisano, had not immediately doubled the thickness of the walls is, in its way, no less informative of the nature of late medieval attitudes and of the triumphs and disasters that attended them.

There can be no doubt whatsoever about Giotto's artistic stature and historical importance. Indeed, he so dominated the Florentine Trecento through his collaborators and followers, from Taddeo Gaddi onwards, that there was until relatively recently a thoroughly misleading tendency to lump together almost every artist in sight under the somewhat derogatory title of 'Giotteschi'. On the other hand, almost everything else about Giotto's career is problematic. His cut down mosaic of the Navicella (c. 1300) in Rome, which was for his contemporaries by far his most important work, is now a ghostly echo of its former self. His signed altarpieces, the Stigmatization of St Francis (Paris, Louvre), the Baroncelli Altarpiece (Florence, Santa Croce) and the polyptych of the Madonna and Saints (Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale), seem to be very largely shop work protected by his signature. However, the Ognissanti Madonna (Florence, Uffizi) is universally accepted as his although it is neither signed nor documented. Other works with a good claim to be considered as his include the Dormition of the Virgin (Berlin) and a Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

The frescoes in the Arena Chapel, Padua (c. 1304-13), depict scenes from the lives of St Joachim and St Anne and the Virgin, and from the Life and Passion of Christ. These frescoes, the masterpiece on which the whole modern concept of his style is based, are unsigned and undocumented, as are those in the Bardi and Peruzzi Chapels (Life of St Francis and Lives of Sts John Baptist and Evangelist) in Santa Croce, which are generally accepted as the only reasonable foundation for an idea of his stylistic evolution during his maturity.

All this, however, is as nothing to the endless controversy which surrounds his date of birth and the attribution to him of the frescoes of the Life of St Francis, painted, probably in the mid-1290s, on the lower walls of the Upper Church of San Francesco at Assisi. For virtually all Italian scholars they constitute the early work of Giotto. For the majority of non-Italian specialists on the subject they do not, and a daunting proportion of the almost 2000 major items in the ever more rapidly accumulating Giotto bibliography is largely devoted to fanning the flames. Fortunately, perhaps, for the sanity of the earnest and discriminating inquirer only a handful of these outpourings can be said to clarify the issue in any substantial way. What should at least be obvious by now is that the frescoes at Assisi are, in detail and as an entire, coherent, carefully planned scheme, like the Arena Chapel frescoes, amongst the seminal achievements in the history of Italian late medieval painting. They stand at the dawning of a new age and their appeal as works of art is not one whit diminished if, as may well be the case, they are not in fact by Giotto.

[2] 'After a long period of restoration carried out by the Opifico delle Pietre Dure, Giotto’s Crucifix has been returned to the central nave of the Santa Maria Novella church. It has been verified that the cross was made originally for the Dominican church. For centuries, it was positioned in the counter façade and thus less visible to both art experts and the parishioners. Only thanks to a large exhibition on Giotto in 1937 did the Crucifix attract the attention it deserved from the art world. However, almost immediately, art critics formed two separate currents of thought on attribution of the cross: Robert Oertel and others claimed it was the work of Giotto, while Richard Offner and others attributed the masterwork to an “unknown maestro”. Offner had also failed to attribute the frescos in the Superior Basilica in Assisi to Giotto.

In the decades that followed, the first hypothesis would be deemed correct — that the Santa Maria Novella Crucifix was indeed Giotto’s. Studies on the crucifix that were carried out during its restoration would confirm this. In fact, the work is characteristic of Giotto’s style: the concreteness of the figures, particularly that of Christ, who seems ‘weighed down’ by death, his muscles tense and stomach sagging. By comparing this work with the artist’s other paintings, and especially his other crucifixes, scholars suspect Giotto may have painted the Santa Maria Novella crucifix in his early years. On the other hand, the iconography is perhaps the most interesting aspect of this artwork. With this cross, Giotto modified the 13th-century model of the Dying Christ on the Cross, exemplified in the artworks of Cimabue and Giunta Pisano. In the works of his predecessors, the bi-dimensional figure of Christ is much more slumped on the cross and the two nails at Christ’s feet are different. Giotto changed this model, after he saw the change in sculptures by Nicola and Giovanni Pisano. In Giotto’s new model of the Dying Christ, he overlapped Christ’s feet, making this the point in which Christ’s physical and moral sufferance converges. He also included the trilingual inscription (in Greek, Hebrew and Latin) at the top of the cross. On the extremes of the arms of the cross, he painted the Virgin Mary and Saint John. At Christ’s feet, there is the image of Calvary hill and the skull of Adam.'

Giotto, Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella | tourism.intoscana.it

|