Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects Giotto | Painter of Florence |

| GIOTTO (1267-1337) |

||

| NOW IN THE YEAR 1276, in the country of Florence, about fourteen miles from the city, in the village of Vespignano, there was born to a simple peasant named Bondone a son, to whom he gave the name of Giotto, and whom he brought up according to his station. And when he had reached the age of ten years, showing in all his ways though still childish an extraordinary vivacity and quickness of mind, which made him beloved not only by his father but by all who knew him, Bondone gave him the care of some sheep. And he leading them for pasture, now to one spot and now to another,was constantly driven by his natural inclination to draw on the stones or the ground some object in nature, or something that came into his mind. One day Cimabue, going on business from Florence to Vespignano, found Giotto, while his sheep were feeding, drawing a sheep from nature upon a smooth and solid rock with a pointed stone, having never learnt from any one but nature. Cimabue, marvelling at him, stopped and asked him if he would go and be with him. And the boy answered that if his father were content he would gladly go. Then Cimabue asked Bondone for him, and he gave him up to him, and was content that he should take him to Florence.

|

|

|

|

|

||

Scenes from the Life of Christ, Resurrection (detail), Cappella degli Scrovegni all'Arena, Padua |

||

Giotto di Bondone, Scenes from the Life of Christ, Resurrection (detail), Cappella degli Scrovegni all'Arena, Padua |

||

|

||

Lamentation (The Mourning of Christ), 1304-06, Cappella Scrovegni (Arena Chapel), Padua |

||

|

||

Giotto, Scenes from the Life of Christ, Lamentation (The Mourning of Christ), 1304-06, Cappella Scrovegni (Arena Chapel), Padua |

||

|

||

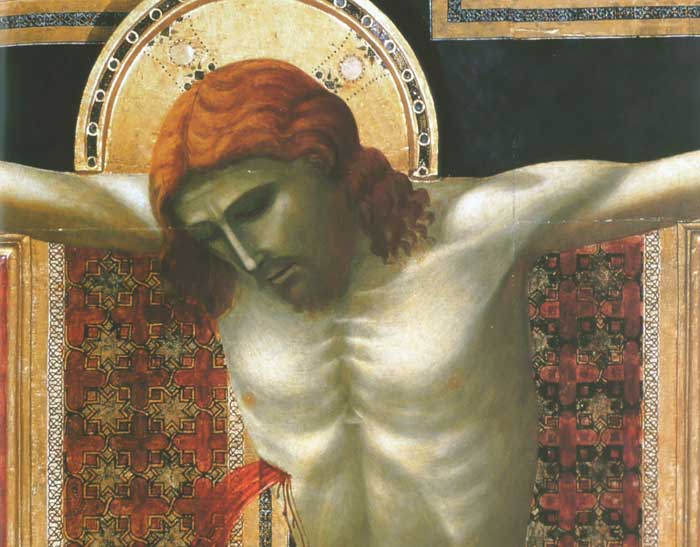

Crucifix (detail), Firenze, Santa Maria Novella |

||

Giotto di Bondone, Crucifix (detail), about 1290-1300, gold and tempera on panel, 578 x 406 cm, Firenze, Santa Maria Novella |

||

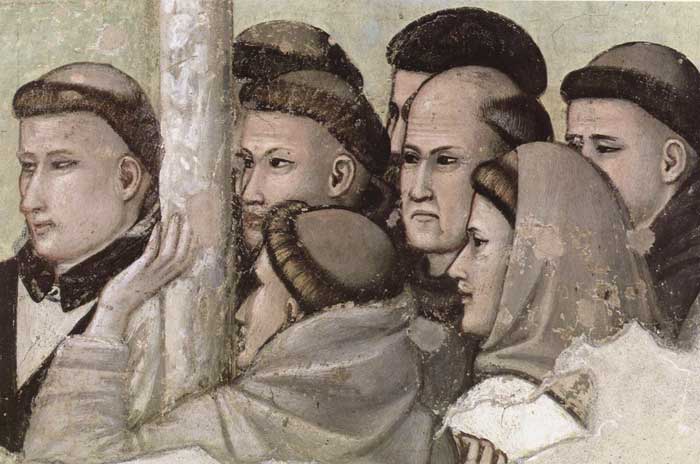

Vision of the Ascension of St Francis, c. 1325, fresco, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence |

||

|

||

Giotto, Vision of the Ascension of St Francis(detail), c. 1325, fresco, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence |

||

|

||

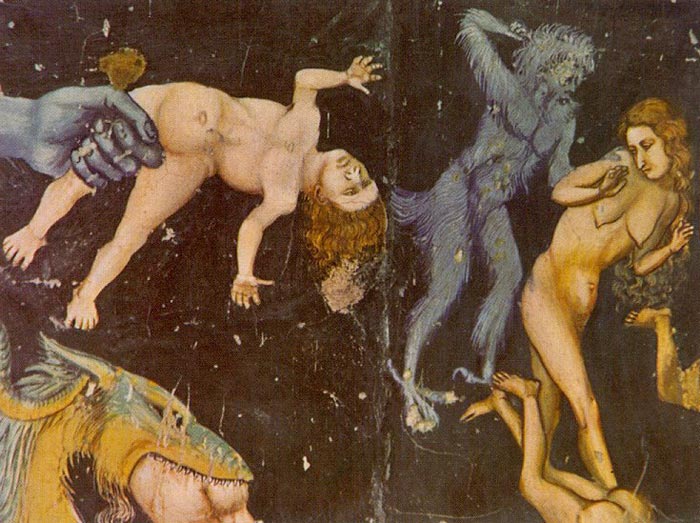

Last Judgment in the Scrovegni chapel in Padua |

||

|

||

Giotto, Last Judgment in the Scrovegni chapel in Padua |

||

|

||

|

||

Giotto, Last Judgment in the Scrovegni chapel in Padua (details), Cappella Scrovegni (Arena Chapel), Padua |

||

The Expulsion of the Devils from Arezzo, 1297-99, Saint Francis of Assisi, Assisi |

||

|

||

Giotto di Bondone, The Expulsion of the Devils from Arezzo, 1297-99, Saint Francis of Assisi, Assisi |

||

|

||

|

||

Giotto di Bondone, The Expulsion of the Devils from Arezzo (detail), 1297-99, Saint Francis of Assisi, Assisi |

||

|

||

Giotto Di Bondone, The Massacre of the Innocents, fresco at Assisi |

||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Paolo Uccello, detail of Five Masters of the Florentine Renaissance (or Fathers of Perspective), a portrait of Giotto), c. 1450, Tempera on wood, 43 x 210 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris [1] |

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

View from Podere Santa Pia

on the coast and Corsica |

||

|

||||

| The towers of San Gimignano | Montalcino |

Florence, Duomo

|

||

|

||||

| Monte Christo. Situated in panoramic position, overlooking vineyards and olive trees, Santa Pia features incredible sunsets... |

||||

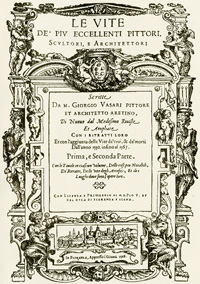

Giorgio Vasari | 'Considered the first art historian and often referred to as the “father of art history”, Varsari was the son of Antonio Vasari (d. 1527), a potter, and Maddelena Tacci (d. 1558). He learned Latin and other humanist disciplines in the 1520’s by Antonio da Saccone and Giovanni Pollastra (1465–1540). Throughout his career, Vasari practiced as an artist. He entered the Arezzo studio of Guillaume de Marcillat, whose previous commissions at the Vatican in Rome brought Vasari into conversance with the work of Michelangelo and Raphael. Vasari’s own painting led the Cardinal of Cortona, Silvio Passerini (1470–1529), tutor of Alessandro and Ippolito de’ Medici, to take Vasari with him to Florence in 1524. There Vasari and the two Medici received further instruction by Pierio Valeriano (1477–1558). Vasari also trained during this time in the Florentine workshops of Andrea del Sarto and Baccio Bandinelli, under Francesco Salviati. Forced to return to Arezzo when the Medici were expelled in 1527, Vasari entered the service of Cardinal Ippolito de’ Medici in January 1532. He studied ancient and modern Roman art and architecture again with Salviati. There he also met Paolo Giovio, an important force for his Vite years later. When Alessandro de’ Medici was murdered in 1537, Vasari was once again devoid of a princely patron. From that point on, he decided to exist on his own. He painted several work for the monks at Camaldoli before journeying to Rome in 1538, accompanied by his assistant Giovanni Battista Cungi. Already he was interested in studying ancient with a view of their effect on contemporary art, the core idea later into his masterwork of writing, the Vite. Vasari went to Venice in 1541.

|

||||

|

|

|

||

Sant'Antimo, between Santa Pia and Montalcino |

Massa Marittima | The towers of San Gimignano | ||