|

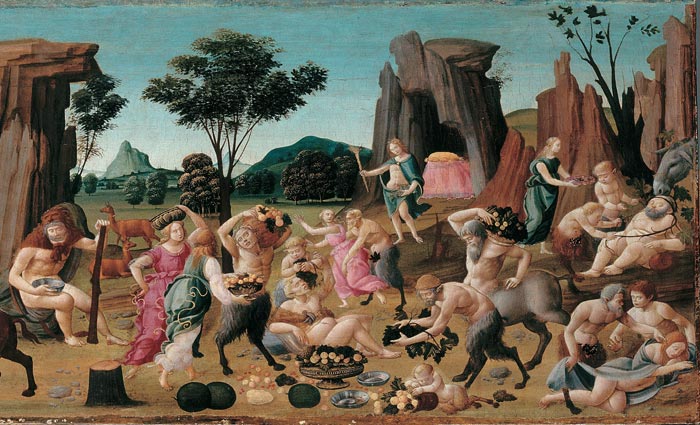

| The Marriage of Thetis and Perseus, c. 1490–1500, detail (left side). Panel of a cassone (wedding chest), Musée du Louvre, Paris |

Bartolomeo di Giovanni |

Bartolomeo di Giovanni, also known as Alunno di Domenico, was an early renaissance Italian painter of the Florentine School who was active from about 1480 until his death in 1501. He studied with and assisted Domenico Ghirlandaio, painting the predella of Ghirlandaio's Adoration of the Magi in the Ospedale degli Innocenti (Foundling Hospital) in Florence, in 1488. Bartolomeo di Giovanni also worked under the guidance of Sandro Botticelli. |

The wedding of Thetis and Peleus |

||

|

||

Bartolomeo di Giovanni, The wedding of Thetis and Peleus, detail. Panel of a cassone (wedding chest), Louvre, Paris |

||

|

||

The wedding of Thetis and Peleus, parents of Achilles, detail. Panel of a cassone (wedding chest), Musée du Louvre, Paris |

||

|

||

The wedding of Thetis and Peleus shows gods, goddesses, nymphs and others processing to the house of the hero Peleus to celebrate his wedding to the beautiful sea-nymph Thetis. Thetis had many suitors, including several of the gods themselves, but when they learned of a prophecy that the son of Thetis would be greater than his father, the gods arranged that she should marry Peleus. Their son was to be Achilles, the greatest of the Greeks to fight at Troy. |

||

The Procession of Thetis |

||

|

||

Bartolomeo Di Giovanni, The Procession of Thetis, 1495, Musee du Louvre, Paris |

||

|

||

|

||

Bartolomeo Di Giovanni, The Procession of Thetis, detail (left side), 1495, Musee du Louvre, Paris |

||

|

||

|

||

Bartolomeo Di Giovanni, The Procession of Thetis, detail (right side), 1495, Musee du Louvre, Paris |

||

|

||

|

||

Sandro Botticelli and Bartolomeo di Giovanni, La historia de Nastagio degli Onesti, 1483, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

||

| In the 1480s Botticelli gained commissions from the families in high society. Increasingly they chose classical themes for the luxurious decoration of their town houses, but they also included some from contemporary literature. In order to be able to carry out his multiple commissions, Botticelli had to work together with other painters as well as members of his own workshop. The four panels conveying the Story of Nastagio degl Onesti, the eighth novel of the fifth day of Boccaccio's Decameron, were produced with the aid of Bartolomeo di Giovanni. The Story of Nastagio degl Onesti is the story of Nastagio, a young man from Ravenna who was rejected by the daughter of Paolo Traversari and abandoned the city to settle on its outskirts. Nastagio degli Onesti, whose beloved initially refused to marry him, finally weds her after all. First of all, however, he must remind her of the eternal agony in hell of another merciless woman, one who had also refused marriage, her rejected lover had to pursue her until he had caught up with her, killed her, torn out her heart and intestines and fed them to his dogs. In the second Panel, Nastagio runs away in fright after witnessing the scene, while the persecution begins again in the background. After his initial sense of repulsion, Nastagio decides to take advantage of the story and invites his beloved to come there for a meal with her family. The third panel shows the guests' reaction to the events, and how Nastagio's beloved uses a maid to indicate that she is willing to marry him. The fourth panel depicts the wedding banquet. The fourth painting naturally represents the woman saying sweetly: "In that case, I'll marry you", and we are present for the marriage of Dona Lucrezia Bini and Ugolino degli Onesti. A considerable contribution to the execution of this panel by Jacopo del Sellaio is assumed. The fourth panel belongs to a private collection, the three others are kept in Madrid, Prado. The paintings were commissioned in 1483 by Antonio Pucci for the marriage of his son, Giannozzo, with Lucrezia Bini. The coats of arms of both families flank those of the Medici on the third panel. Specialists see Botticelli's hand in the overall design and in certain figures. They also detect the participation of his assistants, Bartolomeo di Giovanni and Jacopo del Sellaio. Art in Tuscany | Sandro Botticelli, The Story of Nastagio degl Onesti |

||

Love and Marriage in Renaissance Florence: The Courtauld Wedding Chests, 12 February – 17 May 2009, The Courtauld Institute of Art, Somerset House, Strand, London.

|

||||

Holiday accomodation in Toscany | Podere Santa Pia |

||||

Podere Santa Pia, giardino |

Podere Santa Pia |

Florence, Duomo |

||

Villa I Tatti |

Spoleto |

|||

|

||||

Monte Oliveto Maggiore abbey |

Abbey of Sant 'Antimo |

L'eremo di Montesiepi (the Hermitage of Montesiepi) |

||