|

Villa i Tatti in Settignano, The Villa seen from the bottom of the Italian Garden |

Villa i Tatti in Settignano |

On the green hills that encircle Florence, like a giant Romantic frame for the trim Renaissance architecture of the city below, there lies an ethereal village called Settignano, which has left an indelible mark on the art and literature of the Western world. |

|

Bernard Berenson in the garden at Villa i Tatti, March 1911 |

Villa I Tatti, The Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies History |

| Villa I Tatti is located on an estate of olive groves, vineyards and gardens on the border of Florence and Fiesole. For almost sixty years it was the home of Bernard Berenson (1865–1959), the connoisseur whose attributions of early Italian Renaissance painting guided scholarship and collecting in this field for the first half of the twentieth century. It houses the Berenson collection of Italian primitives, and of Chinese and Islamic art, as well as a research library of 140,000 volumes and a collection of 250,000 photographs. In 1900 Bernard Berenson (1865–1959) married Mary Whitall Pearsall Smith, who had formerly been married to the British politician, Frank Costelloe. Mary Berenson came from a liberal Quaker family from Philadelphia, and had two daughters from her previous marriage, but the marriage to Berenson remained childless. The couple moved to I Tatti shortly before their marriage, first renting the property from the expatriate English aristocrat, John Temple Leader, and then in 1907 buying it outright from Temple Leader’s heir, Lord Westbury. Between 1907 and 1915 the seventeenth-century farmhouse became a Renaissance-style villa under the direction of the English architect and writer Geoffrey Scott, while a formal garden in the Anglo-Italian Renaissance style was laid out by the English landscape architect Cecil Pinsent. Berenson envisaged Villa I Tatti as a “lay monastery” for the leisurely study of Mediterranean culture through its art. He was against academic production, specialization, degrees, and what are now called in the Italian academic world “titoli,” and instead prized the slow maturing of ideas in tranquil contemplation. He considered his own achievement to lie as much in conversation as in writing. Berenson died at the age of 94 in 1959 after bequeathing the estate, the collection, and the library to Harvard University. “Villa I Tatti, The Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies,” as it was officially named, opened its doors to six fellows in 1961. In the intervening five decades since then it has welcomed over 700 fellows and visiting scholars from the United States and Canada, almost all of the European countries east and west, as well as Japan and Australia. |

Villa i Tatti setting

|

||

|

||

Villa i Tatti in Settignano, the Italian Garden |

||

| I Tatti is set in a mythic landscape. The stony hillsides above it, pockmarked by quarries that supplied the pietra serena for Renaissance Florence, bred masons in abundance and some sculptors. Nearby Settignano was home to the sculptor Desiderio da Settignano and to the infant Michelangelo, who was sent there to nurse at his family’s estate (the Villa Michelangelo). A number of houses in the area are given out as the refuge of Boccaccio during the plague and thus the setting of the Decameron. Boccaccio’s Arcadian poem, the Ninfale fiesolano, celebrates the Mensola, a stream flowing through the property. The scarred and over-quarried hillsides were reforested with cypresses by Temple Leader in the late nineteenth century, giving them their present sylvan aspect.[1] Anglo-American villa culture flourished in the area at the turn of the twentieth century. |

||

The Berensons, I Tatti, and Harvard |

||

| Berenson’s esteem for Harvard dated from his youth. He arrived in Boston at age ten as a poor Jewish immigrant from Lithuania. His brilliance was soon recognized and, after finishing the Boston Latin School and completing a year at Boston University, he was supported through Harvard College by wealthier members of Boston society, graduating with the class of 1887. His interests there were in literature and ancient and oriental languages. He trained himself as a connoisseur of early Italian painting by travel throughout Europe and especially Italy, beginning in 1887. As early as 1915 he expressed his intention to leave his house and library to Harvard, and he reaffirmed his intention in 1937, in a letter published in the fiftieth-anniversary volume of his Harvard class.[2] However, Fascism, war, and post-war travail in Italy made Harvard hesitate, and the bequest was only formally accepted by the Harvard Corporation at the time of Berenson’s death in 1959,[3] opening its doors to the first class of fellows in 1961. “Villa I Tatti, The Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies” is thus owned and administered by Harvard University, but it is not the typical American student program abroad. Rather, Harvard conceives of Villa I Tatti as an international institution for the advancement of Italian Renaissance studies on the post-doctoral level. Villa I Tatti is one of three centers for advanced research in the humanities belonging to Harvard but located outside of Cambridge, Massachusetts. The others are Dumbarton Oaks, founded in 1940 for Byzantine, pre-Columbian and garden and landscape studies, and the Center for Hellenic Studies, founded in 1962, both in Washington, D.C. While remaining true to the principal outlines of Berenson’s vision, Harvard altered Berenson’s intended structure by admitting other fields than art history. History and literature were present from the beginning of the Center’s existence as a Harvard research institute, and music followed upon the establishment of a library in music history, generously funded by gifts from Elizabeth and Gordon Morrill. It was Harvard’s insistence on a mix of fields that gives I Tatti its distinctive character. Although “interdisciplinary” was not much in use as a term in 1961, the Center was effectively an interdisciplinary institution from the start. |

||

I Tatti Fellowships |

||

| Each year fifteen full-year fellows are chosen from about 110-120 applicants. All have the doctorate at the time of application but are still in the early phase of their careers. Senior distinguished scholars are not eligible for the fellowship, but every year the director invites some who come without stipend as Visiting Professors in Residence. In a given year perhaps a third of the fellowships tend to be in art history, a third in history, and a third in literature and music. There are no quotas of nation. About half of the fellows over almost 50 years have been from the United States and Canada and half from other countries. In addition to the fifteen year-long fellowships there are a number of short-term awards aimed at specific groups. Since 1993/94 Villa I Tatti has participated in the program funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to bring scholars from the former Soviet bloc countries to American institutions. They have come from Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia, and Berenson’s native Lithuania. There is a similar three-month award, called the Craig Hugh Smyth Fellowship, for Renaissance scholars whose career paths do not normally allow sabbaticals or afford extended summer vacations, such as museum curators. |

||

Library and Fototeca |

||

| Berenson described I Tatti as a library with a house attached. Library spaces were added to I Tatti in 1909, 1915, 1923 and 1948-54. The shelf space created during Berenson’s lifetime was doubled in 1985 when an additional section, the Paul E. Geier Library, was created in one of the former farm buildings. The wing of the library built by Berenson in 1948-54 was recently renovated by the Roman architectural firm of Garofalo and Miura and renamed in honor of I Tatti’s third director and his wife, Craig Hugh Smyth and Barbara Linforth Smyth. Opened in October 2009, the new Smyth Library effectively doubled both the wing’s original shelving capacity and the number of workspaces available there. At his death Berenson left a large personal library of 50,000 volumes, principally dedicated to Mediterranean culture seen through its art and archeology. It also included significant holdings in Chinese, Indian and Near Eastern art, reflecting his collecting interests in those fields. The books were located in a library designed by Cecil Pinsent in 1915 but also scattered throughout the house. It was not conceived as an interdisciplinary Renaissance library from the beginning but as a reflection of Berenson’s personal interests. Italian literature was not strongly represented and music was absent. During the early decades of the institution’s life it became a priority to flesh out the library’s holdings in areas of Renaissance studies not collected by Berenson himself, and to initiate periodical subscriptions in these fields. Transformed from a rich but idiosyncratic personal library into a modern research library, the Biblioteca Berenson aims to provide comprehensive research-level coverage of current scholarly publications in all fields of Italian art, architecture, history, science, medicine, society, culture and literature approximately from 1200 to 1650. Research tools are also acquired in adjacent fields such as northern Europe in the same period, medieval studies, and Byzantine and Islamic cultures around the Mediterranean, especially where these relate to Renaissance Italy. It tries to provide modern editions of many of the works of Greek and Latin literature. Currently it holds some 140,000 volumes, which include 106,000 books, 7,000 offprints, 14,000 auction catalogues, and 23,000 periodical volumes. Over 600 periodicals are currently received, most with complete runs from the start of publication. In 1993 I Tatti joined with three other research libraries in Florence to form a consortium for joint, on-line cataloging, IRIS, which now counts seven member libraries. The Biblioteca Berenson is also one of the 73 libraries that form the Harvard College Library and its holdings are accessible through the Harvard on-line catalogue, HOLLIS. In addition, the considerable electronic resources available through the Harvard library are also available at I Tatti, which makes it one of the largest collections of electronic resources in Italy. |

||

The Morrill Music Library |

||

| Established by a gift from F. Gordon Morrill and Elizabeth Morrill, the Morrill Music library has been part of the Biblioteca Berenson since 1966. It covers all western music from the Greeks to the early baroque period, with emphasis on Italian music composed up to 1640. It includes 4,150 scores and 4,300 critical studies, monographs, treatises, and reference works; it subscribes to 84 journal titles. There is also an extensive microfilm collection of musical manuscripts and early printed books. The aim is to acquire every published work in Italian musicology for the period up to 1640. |

||

The Fototeca Berenson |

||

| The Fototeca Berenson contained 170,000 photographs at Berenson’s death and now contains about 250,000 photographs. They are organized topographically, according to Berenson’s original scheme: Florence, Siena, Central Italy, Northern Italy, Lombardy, Venice, Southern Italy, and within each school by artist and location. A section of the Fototeca is devoted to images of “homeless” works of art—the term used by Berenson for objects that were once on the art market but whose presents locations are now unknown. The versos of many photographs contain handwritten notes by Bernard and Mary Berenson, Nicky Mariano, and other connoisseurs of the first half of the twentieth century. A project to digitize the Fototeca Berenson, making its holdings accessible through the Harvard Libraries’ website, is currently in progress. |

||

The Berenson Archive |

||

| Bernard and Mary Berenson cultivated many friendships through letters. Their letters of their correspondents[4] and some of their own letters are kept in the Berenson Archive, together with diaries, notes, drafts of books, personal photographs and other biographical material. The Archive has been enriched since the founding of the Harvard Center by gifts or acquisitions of papers pertaining to Giorgio Castelfranco, Kenneth Clark, Andrea Francalanci, Frederick Hartt, Giuseppe Marchini, Emilio Marcucci, Nicky Mariano, Roberto and Livia Papini, Valeria Piacentini, Laurance P. and Isabel M. Roberts, Stanislaus Eric Stenbock, and the Whitall Pearsall Smith family. |

||

Collections of Italian painting and Oriental art |

||

| I Tatti is home to the art collection of Bernard and Mary Berenson, which includes an important collection of about 100 late Medieval and Renaissance Italian paintings. The painting collection was formed between ca. 1900 and ca. 1920, with few additions thereafter. Shortly before his death in 1959, Berenson donated his Madonna and Child by Ambrogio Lorenzetti to the Uffizi, which owned two smaller paintings that originally came from the same dismembered altarpiece. The most famous works in the collection, and among the first to be acquired by the Berensons, are three panels depicting St. Francis in Glory, The Blessed Rainieri Rasini, and St. John the Baptist coming from the Sansepolcro Altarpiece by the Sienese painter Sassetta (painted 1437-1444).[5] A comprehensive modern catalogue of the Berenson Collection of Italian paintings is currently in preparation. Bernard Berenson also formed a smaller but important collection of Oriental art, including works from China, Japan, Tibet, Thailand, Java, Cambodia, and Burma.[6] Berenson also assembled a small but significant collection of Near Eastern manuscripts, including an illuminated page from the renowned fourteenth-century Great Mongol (formerly Demotte) Shahnama.[7] Scholarly Programs and Publications I Tatti’s scholarly programs provide a special forum for discussion, and have become increasingly crucial to the Center’s mission of creating bridges with its sister institutions and the international scholarly community. There is also an active program of public lectures by outside scholars and shop-talks by fellows. In addition, I Tatti organizes and hosts one or two symposia or giornate di studio each semester which bring scholars from other countries. Each year I Tatti hosts the Bernard Berenson Lectures, a series of three interconnected lectures on a given theme, presented by a senior scholar of worldwide renown in the field of Renaissance studies. Each cycle of Berenson Lectures is published by Harvard University Press.[8] In addition to publication of the acts of various conferences, select monographs, and the annual Berenson Lectures, there is an annual journal for scholarly essays on Renaissance subjects in English and Italian, I Tatti Studies, which was founded in 1985. Recently a series of monographs on Renaissance history has been initiated with Harvard University Press, the I Tatti Studies in Italian Renaissance History, under the general editorship of Edward Muir.[9] Under the editorship of James Hankins of Harvard, Harvard University Press also publishes the I Tatti Renaissance Library, which is modeled on the Loeb Classical Library and aims to publish the major literary, historical, philosophical and scientific works of the Italian Renaissance written in Latin with modern English translation on facing pages. Forty-one volumes have appeared to date and about 120 more are envisaged in the course of the next decade. The series will put this “lost continent” of Latin literature within the reach of scholars and students in many fields. Both the fellowship and the scholarly events have been enhanced by the completion late in 2010 of the Deborah Loeb Brice Loggiato, site of fellows' studies and a small auditorium, the Gould Hall, on the design of Charles Brickbauer of Baltimore. |

||

Music at Villa I Tatti |

||

| The concerts of early music organized by the Morrill Music Library are an integral part of the academic activities at Villa I Tatti. They range from intimate performances for the I Tatti community, often on period instruments, to those performed by early music groups for a wider audience. The series Early Music at I Tatti, established in 2002 by Joseph Connors with Kathryn Bosi, offers twice-yearly concerts performed by musicians of international renown. These aim to present to the Florentine community innovative programs of early music centering around a particular theme or idea, such as an examination of the concept of humor in Renaissance music (Early Music at I Tatti, II), the role of music in medieval thought (Early Music at I Tatti, I) or the traditional repertoire deriving from the therapeutic effects of music on the bite of the tarantula spider in southern Italy (Early Music at I Tatti, XII). Many offer repertoires which are rarely heard in Italy today, ranging from works by one of the earliest known Florentine composers, Paolo da Firenze (fl. 1390-1425) (Early Music at I Tatti, VII), to music written for the Habsburg court at Vienna in the mid seventeenth century by Italian composers favored by the Austrian emperors (Early Music at I Tatti, IX). Contemporary music is sometimes an integral part of the programs: Early Music at I Tatti, IV juxtaposed Petrarch settings by Renaissance composers with settings by the English composer Gavin Bryars, while Early Music at I Tatti, VIII focused on the fruitful relationship which has developed between contemporary composers and performers of early music. Both concerts featured world premieres of new works written for the occasion. |

||

References

Bibliography

|

||

Villa I Tatti | The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies | www.itatti.it Villa I Tatti, The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies Alternately, you can send your request directly: Tours allow a maximum of eight persons at a time.

Berenson and Harvard: Bernard and Mary as Students | Online exhibition and catalog about Bernard and Mary as Harvard students |

||||

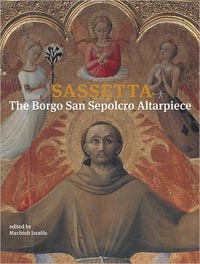

| Sassetta: The Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece, by Machtelt Israels (Editor), James R. Banker (Contributions by), Rachel Billinge (Contributions by), Roberto Bellucci (Contributions by), 2009, Florence & Leiden, Villa I Tatti/ The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies/ Primavera Press. Machtelt Israëls is Researcher in the History of Renaissance and Early Modern Art at the University of Amsterdam. Admirers of the richness, seductive accents and elusive beauty of the paintings of Stefano di Giovanni, known as il Sassetta , will be delighted by the extraordinary, indeed exhaustive depth of this two-volume study devoted to the polyptych once to be seen on the high altar of the church of S. Francesco in Borgo San Sepolcro. Synopsis |

|

|||

|

[1] In 1900, the eminent historian and critic of late medieval and Renaissance art, Bernard Berenson, took up residence at Villa I Tatti. He continued to live there until his death in 1959. In his will, he bequeathed the estate, located on the outskirts of Florence, and his vast collection of books, photographs, and works of art to Harvard University, from which he had received an A.B. in 1887. In leaving I Tatti to Harvard, Berenson wished to establish a center of scholarship that would advance humanistic learning throughout the world and increase understanding of the values by which civilizations develop and survive. He particularly wanted to give younger scholars at a critical point in their careers the opportunity to develop and expand their interests and talents. The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies at Villa I Tatti is devoted to advanced study of the Italian Renaissance in all its aspects: the history of art; political, economic, and social history; the history of science, philosophy, and religion; and the history of literature and music. Each year an international selection committee meets in Cambridge, Mass., to select fifteen post-doctoral scholars in the early stages of their careers to become year-long I Tatti Fellows. In addition, the I Tatti scholarly community includes Research Associates and Visiting Professors, as well as several Craig Hugh Smyth Fellows and I Tatti Research Fellows from Eastern Europe, who stay for periods of three months. The members of the academic community come from institutions across North America, Europe and Australia. Normally, they are members of university and college faculties or of library and museum staffs. Representing a wide variety of interests and methods within the broad area of Renaissance studies, they come to I Tatti for independent study and research both at the Biblioteca Berenson and in other libraries, archives, and collections in Florence and throughout Italy, as well as for the opportunity to think and write, free from their usual academic responsibilities. Villa I Tatti provides the resources of its unique library, which contains approximately 160,000 volumes and an archive of more than 300,000 photographs and other visual materials (the Fototeca Berenson); the library also subscribes to over 600 learned journals. Each I Tatti Fellow is given a study and the opportunity to associate daily with other members of the I Tatti community as well as with the many distinguished Renaissance scholars who continually visit and use the library. A regular series of lectures is sponsored by the Center, and international conferences of an exploratory, usually interdisciplinary, nature are held every year at Villa I Tatti. There is also an active publication program including the journal, I Tatti Studies: Essays in the Renaissance. The Center was founded on the principle that maturing scholars working independently will profit from close association with each other, with leading senior scholars, and with other experts of various interests, ages, nationalities, and levels of achievement. The interchange of ideas and information among scholars with different specialties characterizes both formal and informal communication at I Tatti. Mr. Berenson's dream of a cultural center where the heritage of the past would be preserved and fruitfully studied has been realized at I Tatti to an extent even he could not have anticipated. The long list of highly distinguished publications that have emanated from the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies in the more than three decades of its existence, the roster of world-renowned scholars who have been Fellows, and the often moving testimonials of all who have been involved with this institution combine to attest the important position I Tatti occupies in Italian Renaissance studies today. Besides the villa, his library, and an archive of photographs and other visual images, Mr. Berenson left Harvard his collection of some 120 works of Renaissance and oriental art, which he intended should remain distributed throughout the house. His bequest also included his archive of correspondence and papers, as well as the farmlands and gardens surrounding the Villa. He saw both the collection and the setting as providing encouragement to thoughtful and creative intellectual meditation. [2] Cecile Pinsent was an English architect who designed and built Tuscan villas and gardens for the English speaking community in Tuscany between 1910 and 1940. He visited Florence with his friend Geoffrey Scott on a tour of Tuscan architecture. Scott became librarian to the American art historian Bernard Berenson and Pinsent worked with him on the Villa I Tatti. This provided an entree to a wealthy circle of clients, including Charles Augustus Strong, Alice Keppel and Lady Sybil Cutting, the mother of Iris Origo. Gardens designed by Cecil Ross Pinsent include Villa Capponi Garden, Villa i Tatti, Villa La Foce and Le Balze Garden. |

||||

| This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia article Villa I Tatti , published under the GNU Free Documentation License. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Villa I Tatti. |

||||

Hidden secrets in Tuscany | Holiday house Podere Santa Pia |

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, view from the garden on the valley below |

Il parco dei Mostri di Bomarzo |

||

|

||||

|

||||

| Precisely because of its size, slope, scenery and slower rhythms, Settignano is best seen in the 19th-century manner, on foot. There are several recommended itineraries for the healthy walker or runner. The most idyllic start is at the bridge, Ponte a Mensola, at the junction of the Via Vincigliata and the Via Gabriele d'Annunzio. Following the stream along the Via Vincigliata to the Via Corbignano, one finds two marble plaques of the major artists and writers who were born or lived in and around Settignano. Several of the writers were English, and the foreign colony that lived on the hills overlooking Florence until World War II also for a time included Mark Twain. A Village of Cypress and Vines, by SUSAN LUMSDEN Choosing one of the Florence walking tours you'll be able to visit the world-famous museums of the Uffizi and Accademia Galleries, discovering the main historical and artistic treasures of the city. The tours focus on Florence's major sights and attractions, including the Duomo, the Ponte Vecchio and the city's famous churches and Renaissance palaces. Novelist Henry James called Florence a “rounded pearl of cities -- cheerful, compact, complete -- full of a delicious mixture of beauty and convenience.” The best way to experience the Italian city’s artistry, history and joy of life is by walking the same paths that the Medicis, Michelangelo and James once used. And to reach Villa I Tatti, there is the itinerary From Fiesole to Settignano. 1 | A Walk Around the Uffizi Gallery 2 | Quarter Duomo and Signoria Square 3 | Around Piazza della Repubblica 5 | San Niccolo Neighbourhood in Oltrarno 6 | Walking in the Bargello Neighbourhood 7 | From Fiesole to Settignano

|

San Miniato al Monte |

|||

|

||||

|

||||

Spectacular panoramic scenery in Podere Santa Pia, with views that stretch all the way to the Mediterranean sea and the islands of Montecristo and Corsica. |

||||