Villa Gamberaia |

Set high upon the crest of the hill, the Gamberaia stands above the adjacent agrarian countryside. Its terraces are filled with simple but elegant architecture and ordered greenery. Entering through its gates, one is struck by its other-worldliness, the surreal character of the enclosed space. One cannot foil to see its beauty, to feel its grandeur, to marvel at its intimacy and to puzzle at the assemblage of separate garden spaces within. The siting and composition, a result of over four centuries of over-lapping interventions by its owners and their architects, is a simple yet subtle progression of garden design. Yet the villa is on integral port of the Tuscan landscape and its agreement with its surrounds clearly evident to the educated eye.[0] Jeanne Keshka |

|

'Known as a ravishing beauty from birth, Jeanne Keshka was born in Nice, France, and was raised in the late 1860s in Florence, Italy. As a young adult, in the early 1805, she went to Paris as an art student and circulated socially with the students of the male-only Ecole des Beaux-Arts. She was also reputed to be a courtesan among the Parisian nobilities; her signature feature was her collection of jeweled toe-rings. She mixed freely in these two circles and is even recorded as one of Gertrude Stein's friends attending her famous soirees. (...) |

| During the eighteenth century the Capponi family made various improvements in the grounds, embellishing them with statuary and fountains. The preservation of the garden at Villa Gamberaia Edith Wharton astutely attributed to its "obscure fate" during the nineteenth century, when more prominent gardens with richer owners in more continuous attendance had their historic features improved clean away. Shortly after Wharton saw it, the villa was purchased in 1895 by the Romanian Princess Jeanne Ghyka, sister of Queen Natalia of Serbia[10], who lived here with her American companion, Miss Blood.[11] At the end of the 19th century, Princess Ghyka began the transformation of the old parterre de broderie into beautiful flower-bordered pools, enclosed at the southern end by an elegant cypress arcade, while the following owner, the American-born Mathilda Cass Ledyard, Baroness von Ketteler, introduced the wide box borders and topiary forms that still give the parterre its distinctive architectonic effect. It is believed that the sculptures found throughout the gardens were works by Princess Ghyka, who was educated at the School of Fine Arts in Paris. Mr. and Mrs. Berenson of Villa I Tatti were among the privileged few who had the entrée to Villa Gamberaia at the time of Princess Ghyka’s ownership. |

||

|

||

The liquid and the solid… nowhere else in my recollection have these been composed with such elegant refinement of taste on so human a scale.(…) The whole conception of a garden to live with and in on intimate terms, responsive to loving care and constant culture, has been realized and expanded. It leaves an enduring impression of serenity, dignity and cheerful repose. Harold Acton, Tuscan Villas. (London 1973). |

||

Opening hours |

||

The gardens are opened from 9am to 6 pm. (Sunday 9am to 5pm) Address |

||

History |

||||

| The villa, originally a farmhouse; was owned by Matteo Gamberelli at the beginning of the fifteenth century. His sons Giovanni and Bernardo[6] became famous architects under the name of Rossellino. After Bernardo's son sold it to Jacopo Riccialbani in 1597, the house was greatly enlarged. The designer of the Villa Gamberaia has not been identified, but it is known that the villa building was begun in 1610 for Zanobi Lapi whose nephews and heirs first laid out the gardens between 1624 and 1635. [7] Documents of his time mention a limonaia and the turfed bowling green that is part of the garden layout today. In 1717 La Gamberaia passed to the Capponi family as one of his ten or more poderes. Water rights were then in dispute as the Capponis drained lands to the east and channeled water throughout the site. Andrea Capponi laid out the long bowling green, planted cypresses, especially in a long allée leading to the monumental fountain enclosed within the bosco (wooded area), and peopled the garden with statues, as can be seen in an etching by Giuseppe Zocchi dedicated to marchese Scipione Capponi,[8] which shows the cypress avenue half-grown and the bowling green flanked by mature trees that have since gone. "Certainly the minds of the Florentine family of Capponi were original and inventive. First, in 1570 they created the beautifully detailed asymmetrical garden at Arcetri overlooking Florence ..... and in 1717 they finally synthesized and completed the slowly evolving complex of Villa Gamberaia at Settignano across the Arno valley whose concept of a domestic landscape is by general concent the most thoughtful the western world has known." [Geoffrey Jellicoe, Italian Gardens of the Renaissance, (London, 1925 and 1953)] The villa already stood on its raised platform, extended to one side, where the water parterre is today. The parterre was laid out with clipped broderies in the French manner in the eighteenth century, as a detailed estate map described by Georgina Masson demonstrates. Olive groves have always occupied the slopes below the garden,[8] which has a distant view of the roofs and towers of Florence. The monumental fountain set into a steep hillside at one lateral flank of this terraced garden has a seated god flanked by lions in stucco relief in a niche decorated with pebble mosaics and rusticated stonework. In 1925 Princess Jeanne Ghyka sold the property to the American-born Baroness von Ketteler. In 1952 Marcello Marchi acquired it and restored the house, which had been badly damaged during World War II. The Gamberaia now belongs to Signor Marchi’s son-in-law Luigi Zalum (see the anthology Revisiting the Gamberaia, ed. P.J. Osmond, Florence 2004). During World War II, the villa was almost completely destroyed. Marcello Marchi restored it after the war, using old prints, maps and photographs for guidance. |

||||

|

||||

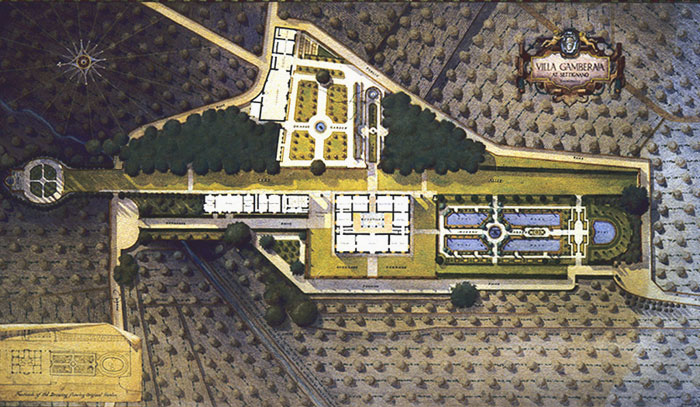

Edward G. Lawson. Measured drawing shows rendered site plan. The small inset shows a facsimile of old drawing showing original garden. |

||||

| 'The Gambaraia has been measured several times, but only in modern history.The first plan was recorded in 1906 by the English landscape architect, Indigo Triggs, and showed the new Ghyka water garden along with its classical armature.. There were, however, many inaccuracies in the drawing. It wasn't until 1919 that the villa and its gardens were accurately measured by Edward G. Lawson, the laureate of the Rome Prize in Landscape Architecture who was then in residence at the American Academy in Rome. Lawson's drawings recorded the the entire villa and recorded the garden at its peak of refinement and elegance.'[12] |

||||

|

||||

[0] R. Terry Schnadelbach, Hidden Lives / Secret Gardens: The Florentine Villas Gamberaia, La Pietra And I Tatti, Universe, 2010, p.6 Hidden Lives / Secret Gardens is a synthetic history about gardens and human sexuality. Schnadelbach exposes the engaging and intertwined lives of a group of expatriates, their secluded hillside villas and secret new gardens that ushered a new direction in garden design. Three successive new gardens at Villas Gamberaia, La Pietra and I Tatti were among the earliest Modernist landscapes and were an inspiration many landscape professionals in Britain and America. While hidden lives / secret gardens manuscript focuses on the revival of the Renaissance aesthetic in Florence and paints a picture of each garden's history, it explores the new and emerging field of sexual psychology through the hidden lives of the Villa's owners and designers, revealing their artistic life styles, their commercial and sexual mores. For a description of the Villa Gamberaia garden, see pp 26-78 or click here. ISBN: 1440131155 - Hidden Lives / Secret Gardens: The Florentine Villas Gamberaia, La Pietra And I Tatti | www.openisbn.com Michel de Montaigne, Travel Journal (1580–1581). Transl. Donald M. Frame. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1983. An Intimate Garden With Grand Appeal: Villa Gamberaia at Settignano | www.members.shaw.ca Osmond, Patricia, ed. “Villa Gamberaia: Sources and Interpretations,” in Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes. Vol. 22, No. 1, Spring 2002 (Special issue). Osmond, Patricia, ed. Revisiting the Gamberaia: An Anthology of Essays on Villa Gamberaia. Florence: Centro Di della Edifimi, 2004. Kimberlee S. Stryker, 'Pietro Porcinai and the modern Italian garden', Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes: An International Quarterly, Volume 28, Issue 2, 2008, pages 252-269 Italian landscape architect Pietro Porcinai (1910-1986) brought modern garden design to a nation rooted in classic garden tradition. His designs are based on a strong identification of ‘place’ and sensitivity to ecological concerns, while they are also innovative in construction and form. He was one of the 17 founding members of the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA) in Cambridge in 1948. Though lesser known than his contemporaries Geoffrey Jellicoe, Sylvia Crowe, Thomas Church and Roberto Burle-Marx, Porcinai is one of the most important landscape designers of the twentieth century. Porcinai’s place in the canon of modern landscape design has only now started to receive its rightful appreciation. [Taylor & Francis Online | www.tandfonline.com] |

||||

Settignano

|

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, view from the garden on the valley below |

Il parco dei Mostri di Bomarzo |

||

| Villa Cahen has a well-equipped public park while the latter has the state-owned park with Villa Cahen, in Art Nouveau style, and the hidden jewel in the center of the Park. In the marvellous gardens you can find various and rare arboreal and herbaceous species. |

Villa I Tatti, near Settignano, outside Florence |

Castello Torre Alfina |

||

|

Walking around Florence | 7 | From Fiesole to Settignano |

||||

After leaving England, Cecil Pinsent settled in Florence in 1907, where he joined the circle of the famous art historian and critic, Bernard Berenson, and Geoffrey Scott. |

||||

Bernard Berenson |

||||

March 4th, (1948) I Tatti |

||||

Cecil Pinsent |

||||

Today... the garden should give the impression of a house extended into the open-air, and its diverse aspects should succeed one another in such a way that when walking through it one is confronted by a series of impressions rather than a single effect... |

||||

Harold Acton |

||||

| Nowhere else in my recollection have the liquid and solid been blended with such refinement on a scale that is human yet grand without pomposity... It leaves an enduring impression of serenity, dignity and blithe repose.... Harold Acton, Tuscan Villas (London, 1973) p. 151. |

||||

R. Terry Schnadelbach |

||||

| The Villa Gamberaia of the Princess Ghyka era was a wonderfully small villa that the Princess endeavored to make only better. If architecture is frozen music, then the Gamberaia's gardens were composed like a waltz, swirling from one space to the next. There are no straight line marches in experiencing this site. One constantly turns, moving smoothly through gardens that are connected one to other. One terrace wraps around the main villa only to meet another leading away in the opposite direction. The waltz ends in a grand, sweeping panoramic view or, in the opposite direction, in the oval hillside grotto. The waltz is danced through brilliant sunlight into the darkest shade, then back into light, in an ever-changing sequence. With direct connections, the eye, as well as the body, turns this way, then that; each space ending where the next begin – all in a continuous movement. The Gamberaia garden's musical tone throughout is a constant - either the green architectural walls of the planting or the yellow ochre walls of the villa buildings. R. Terry Schnadelbach, Hidden Lives / Secret Gardens: The Florentine Villas Gamberaia, La Pietra And I Tatti, Universe, 2010, p.26 |

||||

| The Villa Gamberaia is a member of the Grandi Giardini Italiani, an association of major gardens in Italy. Its members include some of the most important gardens in Italy. List of member gardens | Fondazione Pompeo Mariani (Imperia), Giardini Botanici di Stigliano (Roma), Giardini Botanici di Villa Taranto (Verbania), Giardini Botanici Hanbury (Ventimiglia), Giardini della Landriana (Roma), Giardini La Mortella (Napoli), Giardino Barbarigo Pizzoni Ardemani (Padova), Giardino Bardini (Firenze), Giardino dell'Hotel Cipriani (Venezia), Giardino di Boboli (Firenze), Giardino di Ninfa (Latina), Giardino di Palazzo del Principe, Giardino di Villa Gamberaia (Firenze), Giardino Ducale di Parma, Giardino Esotico Pallanca (Imperia), Giardino Giusti (Verona), Giardino Storico Garzoni (Pistoia), Gardens of Trauttmansdorff Castle (Merano), Giardino del Biviere (Siracusa), Serraglio di Villa Fracazan Piovene (Vicenza), Vittoriale degli Italiani (Brescia), Cervara, Abbazia di San Girolamo al Monte di Portofino (Genova), Venaria Reale, Museo Giardino della Rosa Antica (Modena), Museo Nazionale di Villa Nazionale Pisani (Venezia), Oasi di Porto (Roma), Orto Botanico dell'Università di Catania, Palazzo Fantini (Forlì), Palazzo Parisio (Malta), Palazzo Patrizi (Roma), Parco Botanico di San Liberato (Roma), Parco del Castello di Miramare (Trieste), Parco della Villa Pallavicino (Verbania), Parco della Villa Reale di Marlia (Lucca), Parco di Palazzo Coronini Cronberg (Gorizia), Parco di Palazzo Malingri di Bagnolo (Cuneo), Parco di Pinocchio (Pistoia), Parco Giardino Sigurtà (Verona), Parco Idrotermale del Negombo (Napoli), Parco Paternò del Toscano (Catania), Parco Storico Seghetti Panichi (Ascoli Piceno), Varramista Gardens (Pisa), Villa Arvedi (Verona), Villa Borromeo Visconti Litta (Milano), Villa Carlotta (Como), Villa del Balbianello (Como), Villa della Porta Bozzolo (Varese), Villa d'Este (Como), Villa d'Este (Tivoli), Villa di Geggiano (Siena), Villa Durazzo (S. Margherita Ligure, GE), Villa Farnese di Caprarola (Viterbo), Villa Grabau (Lucca), Villa La Babina (Imola), Villa La Pescigola (Massa), Villa Lante (Viterbo), Villa Melzi d'Eril (Como), Villa Montericco Pasolini (Imola), Villa Novare Bertani (Verona), Villa Oliva-Buonvisi (Lucca), Villa Peyron al Bosco di Fontelucente (Firenze), Villa Pisani Bolognesi Scalabrin (Padova), Villa Poggio Torselli (Firenze), Villa San Michele (Napoli), Villa Serra (Genova), Villa Trento Da Schio (Vicenza), Villa Trissino Marzotto (Vicenza), Villa Vignamaggio (Firenze). Grandi Giardini Italiani (Italian) | www.grandigiardini.it |

||||

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Villa Gamberaia and published under the GNU Free Documentation License, and information from the Toscane Regione website (www.cultura.toscana.it). Wikimedia Commons has media related to Medici villas. |

||||

| Tuscan villas Selected bibliography |

||||

| Judith Bernandi, Italian Gardens, Rizzoli (September 14, 2002), ISBN-10: 0847824950 | ISBN-13: 978-0847824953 Since the earliest Roman settlements, Italians have been expertly cultivating their land into beautiful and creative displays of nature, where terraces and walkways, plants and flowers, water and statuary are combined to provide a unique ad inspiring setting. The Italian garden has greatly evolved throughout the ages, taking on different forms, favoring different plants, and serving different purposes. Early Italian gardens made use of citrus, still regarded as an essential element for its bright fruit and shiny leaves. The ancient art of the topiary was revived in the Renaissance for its drama and elegance, and the refined parterre was developed to spread forth from the great palazzos and provide a dramatic view from their upper stories. Later, in the nineteenth century, the influence of the English garden took hold, with its meandering paths, asymmetrical lakes, and blossoming trees. In Italian Gardens, author Judith Wade explores more than five hundred years of this tradition, discussing each of these developments and transporting the reader to thirty-seven of the most captivating gardens of Italy. Eleven regions are visited, from Lombardy and Piedmont in the north, to the island of Sicily in the south. Both small and grandiose, historic and contemporary gardens are featured. Travel with Wade to the aristocratic Villa Favorita in Lugano, where an avenue of cypresses welcomes those who approach; the English-style park of Villa Novare Bertani in Verona, with its seventeenth-century wine cellar; the eighteenth-century Avenue of the Camelias at Lucca's Villa Reale, where the American artist John Singer Sargent painted; and great examples of contemporary Italian landscapes, like La Mortella in Naples, which boasts more than eight hundred species of rare plants. Buy it at Amazon Sophie Bajard, Raffaello Bencini, Villas and gardens of Tuscany, Terrail, 1993 |

||||