Villa La Foce |

La Foce stands on a ridge of hills that forms the watershed between two valleys, the Val d'Orcia and the Val di Chiana. The land beyond the house and garden falls dramatically away and the vast, open view is stopped only by the unmistakable profile of Monte Amiata. |

|

||

A view across the garden towards a horizon dominated by the volcanic peak of Monte Amiata. La Foce stands on a ridge of hills that forms the watershed between two valleys, the Val d'Orcia and the Val di Chiana. The land beyond the house and garden falls dramatically away and the vast, open view is stopped only by the unmistakable profile of Monte Amiata. |

||

Like many of the buildings at La Foce, the garden was designed by a now-forgotten British architect, Cecil Ross Pinsent (18841963), who had arrived in Florence, aged twenty-four, to join his friend Geoffrey Scott on a Tuscan study tour. Scott had been appointed secretary/librarian to art historian Bernard Berenson; and though the pair had little practical experience (Pinsent seems to have designed one garden in England), they were soon put in charge of the new buildings and planting at Berenson's famous Villa i Tatti. Pinsent went on to create gardens for Berenson's friends in and around Florence: the philosopher Charles Augustus Strong, Alice Keppel (the great-great-grandmother of Camilla Parker Bowles), and Iris Origo's mother, Lady Sibyl Cutting, at the Villa Medici in Fiesole. He began work at La Foce in the Twenties while the Origos were still on their honeymoon.

|

||

|

||

| 'The original house at La Foce was an inn. It was built at the end of the fifteenth century by the Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala, a hospital and charitable institution with vast land holdings to the south of Siena. It stood beside the Via Francigena, an ancient road linking Canterbury to Rome. The road was always busy, and a steady stream of pilgrims and merchants would have broken their journey here. By the time Antonio and Iris Origo bought La Face in 1924 many of the buildings on the 3000-hectare (7413-acre) estate were derelict and the land was poor and neglected. In winter the farm was often battered by the freezing tramontana wind and in summer it was scorched by the sirocco. The young couple, yet to be married,· had set themselves an enormous task but they were undaunted. Their vision of their own future and the future of La Face is beautifully summarised by Iris Origo in her autobiography, Images and Shadows. We knew at once that this vast, lonely, uncompromising landscape fascinated and compelled us. To live in the shadow of that mysterious mountain, to arrest the erosion of those steep ridges, to turn this bare clay into wheat fields, to rebuild these farms and see prosperity return to their inhabitants, to restore the greenness of these mutilated woods - that, we were sure, was the life that we wanted. That is what they wanted, and that is what they did, with extraordinary dedication and determination. Iris and Antonio employed Cecil Pinsent, an English architect who had made his career among the Anglo-American expatriate community in Tuscany, to design a new wing for the house, thus creating a sheltered courtyard behind it, to restore the farmhouses and other buildings on the estate and to design a kindergarten, a clinic, a school, a chapel and a dopolavoro, or club house, where labourers on the estate could meet after work. The garden was built in four phases. The first garden makes perfect sense to anyone who has lived in a windswept landscape. It encloses the area immediately outside the new wing of the house, creating a serene, sheltered space that seems to moor the building in the enormous landscape. It is a green garden, enclosed by high walls and bay hedges, and fu:nished with a box parterre and a simple fountain. The second garden was much larger and more complex. Pinsent cut the sloping site into gentle terraces which he planted with broad, box-lined enclosures. Pots of lemons were arranged on stone plinths inside the hedges and the new area soon became known as the lemon garden. Pinsent was the garden architect, but the planting was Iris's responsibility. She may have grown up in Italy, but her gardening style was almost entirely Anglo-Saxon. She ordered seeds from Suttons in England, filled the beds with spring flowers and irises and covered the walls with roses, jasmine and honeysuckle. In 1938 Pinsent built a pergola to follow the sinuous contour of the hill above the lemon garden. In the narrow space between the pergola and the hillside he made a rose garden with stonelined beds. Iris Origo's garden notebook contains a list of the ten standard roses that she ordered to fill the beds. The final phase of garden building came in 1939, just before the war. The lower garden, which is overlooked by the lemon garden, projects into the valley like the prow of a ship. A mighty double staircase leads down to it, but this is really a garden made to be seen from above. It is entirely enclosed by cypresses, and filled with wedge-shaped box parterres that taper towards a pool at the garden's far end.,.', ; Looking back at over five decades of gardening at La Foce, Iris Origo wrote:

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

The monumental double staircase that links the lower garden to the lemon garden on the terrace above. |

||

|

||

|

||

Pergola covered with roses and wisteria |

||

| The garden follows the classic landscape formula: confinement, openness, surprise. Right up against Pinsent's extension to the old inn is a hortus conclusus (enclosed garden) with a rustic-columned pergola covered with roses and wisteria, a box parterre framing a little stone fountani, and a laurel arbour containing a stone seat and table. Nothing suggests there is anything outside it but a pathway that carries the eye through the hedges that flank it to a clump of cypresses on the horizon. This path leads you out into a series of terraced, Renaissancestyle chambers, surrounded by cushion-tupped box hedges and set at intervals with lemon trees in terracotta pots, like those at the Villa Reale in Marlia. Above the chambers are a graceful, pillared wisteria-festooned pergola and a flight of stone steps leading up to a rose garden, around which curves a vine-covered pergola like a long, living feather boa. The overall impression is of a restrained English exuberance swarming over and softening a rigorously classical order and line. As you reach the balustrade at the end of the pathway, there suddenly appears beneath you a lower garden projecting like the deck of a shift over the distant valley. Centred on the cypress-clump and a statue in front of i~ it is a stage set which borrows from Renaissance precedents like the Palazzo Piccolomini in Pienza. At the near end are four superb Magnolia grandiflora growing within two-tiered box hedges; in front of these, double box beds taper like arrow heads towards a pool at the statue's feet. The entire garden is protected by a thick curtain of immense cypress hedges; beyond and around is nothing but sky and mountains. |

||

|

Villa La Foce, cemetery, where Iris Origo and her husband are buried, alongside Gianni. | |

|

||

The cypresses that twine up a hill side near Chianciano Terme have become an emblem of Tuscany. But they also have a story, for they were planted by Marchese and Marchesa Origo (the writer Iris Origo) as part of a scheme to improve the landscape of what was then among Italy's most desolate regions. They also, no doubt, softened the view from the masterpiece the idealistic young couple created nearby, at what had been until their arrival a wayside inn: one of the most dramatic twentieth-century gardens. |

||

|

||

The famous winding road with cypresses |

||

Monty Don's Italian Gardens - La Foce, Tuscany

|

||||

World-famous gardener Monty Don presents this enchanting four-part series that celebrates Italy's most beautiful gardens. BBC | Monty Don stops at La Foce on his grand tour of Italy

|

||||

|

||||

| World-famous gardener Monty Don stops at La Foce on his grand tour of Italy , discovering how, like a piece of sculpture, Renaissance gardens were created as works of art. [5] | Villa la Foce on YouTube |

||||

|

||||

| [1] It is hard to imagine what would induce a shy, conscientious Englishwoman to leave the domesticity of Florence and settle in a bleak landscape three and a half hours journey from her family and friends. In her autobiography she admits to having felt uncomfortable amid the aimless, affluent expatriates. Perhaps this sense of drifting, compounded by her mixed heritage and cosmopolitan upbringing, drove her to put down roots, even in such alien soil. As a writer, Origo was fascinated by the local peasants, noting their customs and superstitions, charting their lives in meticulous detail, particularly in the early days when the harvest was done by hand with long rows of reapers, binders and gleaners, bending low to the ground. Unusually, however, Origo could see beyond the picturesque scenes to empathize with the hardship involved in such a primitive lifestyle; after describing in sensuous detail the men naked to the waist, glistening with sweat, working the stone olive-press through the night by oil lamp, she notes, 'Now, in a white-tiled room, electric presses and separators do the same work in a tenth of the time .... One can hardly deplore the change; yet it is perhaps at least worth while to record it.' And record it she did, depicting the disappearing rural lifestyle in her autobiographical writings, celebrating the country's past in studies of the nineteenth-century poet Giacomo Leopardi, the fourteenth-century innkeeper's son turned politician Cola di Rienzo, the medieval Saint Bernardino, Byron's lover Countess Guiccioli, his daughter Allegra, several collections of biographical essays and The Merchant of Prato, a study of the medieval merchant, Francesco Datini.[3] [2] Helena Attlee, Italy's Private Gardens: An Inside View, pp. 104-109, Frances Lincoln, 2010 [3] Katie Campbell , A modern pastoral in an ancient landscape - Iris Origo's La Foce, in Paradise of Exiles: The Anglo-American Gardens of Florence, pp. 154-167. [4] From Giardini in Toscana - Gardens in Tuscany Un viaggio attraverso la storia dei giardini • A journey through the history of gardens, pp. 35-36 | www.regione.toscana.it [5] The hour long programme was the first in a series of four, covering Rome, Florence and elsewhere in Italy. Monty Don was visiting:

|

|

|||

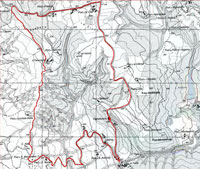

| Villa La Foce | Anello La Foce di Chianciano – Riserva di Lucciola Bella – Palazzone – Castelluccio |

||||

| After visiting Villa La Foce, we start our journey that will take us all the way to Castelluccio. Paved roads before and then white trails, with short deviations to discover the beauty of nature, roads bordered by cypress trees that take us to discover the natural reservoir of Lucciola Bella. Trekking in Toscana | Anello La Foce di Chianciano – Riserva di Lucciola Bella – Palazzone – Castelluccio [Fonte: CAI – Sez. Valdarno Superiore] |

|

|||

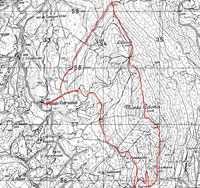

| Villa La Foce | Anello La Foce - Vetriana – Monte Cetona |

||||

Monte Cetona (1148 m) is in the south eastern section of Tuscany, near the border with Umbria. |

|

|||

Hidden secrets in Tuscany | Holiday house Podere Santa Pia |

||||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, view from the garden on the valley below |

Podere Santa Pia | ||

|

||||

Montepulciano |

Villa I Tatti |

|||

|

|

|

||

Villa La Foce, entrance gate with a

|

Villa La Foce | Castelluccio

|

||

Montepulciano |

||||

| Montepulciano, is built along a narrow limestone ridge and, at 605 m (1,950 ft) above sea level. The town is encircled by walls and fortifications designed by Antonio da Sangallo the Elder in 1511 for Cosimo I. Inside the walls the streets are crammed with Renaissance-style palazzi and churches, but the town is chiefly known for its good local Vino Nobile wines. a long, winding street called the Corso climbs up into the main square, which crowns the summit of the hill. The Duomo was designed between 1592 and 1630 by Ippolito Scalza. The façade is unfinished and plain, but the interior is Classical in proportions. It is the setting for an earlier masterpiece from the Siena School, the Assumption of the Virgin triptych painted by Taddeo di Bartolo in 1401. In the 15th century, Michelozzo added a tower and façade to the original Gothic town hall, the Palazzo Comunale. The building is now a smaller version of the Palazzo Vecchio. On a clean day, the views that can be seen from the tower are superb. As in Cinigiano, Calici di stelle is the main summer event in Montepulciano. The Strada del Vino Nobile offers an enogastronomic tour in the various Quarters of Montepulciano with wine tastings and a typical dinner under the guidance of expert Sommeliers and never the less various entertainments and music shows. |

||||

| The pilgrimage church of The Madonna of San Biagio lies just outside of the town of Montepulciano. Its symmetrical greek-cross plan reflects the High Renaissance drive towards perfection in a combination of squares and circles. The church was begun by the architect Antonio di Sangallo the Elder in 1518 and is considered one of the first great examples of Cinquecento architecture. The concept for a centrally planned church obsessed High Renaissance architects like Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Leonardo, thAntonio di Sangalloe Elder and the Younger, Bramante, and Michelangelo. This is based on the Vitruvian idea that man, which represents perfection, can fit into both a square and a circle. As man provides the measure for these forms, if we create a space based on a combination of these forms, we are likely to understand that space inherantly. So, many plans for churches in the Cinquecento were based on greek cross plans and tried to combine these perfect shapes. But, many ACTUAL churches do not! Due to the impraticality of not having a nave down which to process, architects and patrons often found the need to give the space a certain directionality by differentiating at least the apse. S. Biagio is in fact one of these cases, but it comes very close to the Renaissance ideal. As you can see in the ground plan, the whole complex except the rounded apse fits into a square that can be, of course, subdivided into smaller squares. The church as it stands today took about a hundred years to complete, and in fact it was never finished according to plan. You approach it from the side that has a rounded apse. Going around to the right side, this would have been the facade, which was planned to have two identical towers. One tower was completed while the other stands as an odd, incomplete structure. The towers flanking this side would have provided a sense of directional axis towards the apse. The central core of the structure is articulated by three flat facades that appear to be identical; the rounded apse occupies the lower part of a fourth facade that also provides this repetition in design. The interior is a a beautiful open space that, at certain times of day, is illuminated by dramatic directional light. The sense of symmetry is apparent as one observes the equal vaults on three sides. The interior is entirely decorated in travertine. Architectural elements like engaged columns and Doric or Tuscan pilasters offer repetition and division of space. The arches are punctuated by strongly extruding rosettes. The vocabulary is a specific ancient one that references the Basilica Aemilia in the Roman Forum, as has been observed by Lehmann in 1982. [Phyllis Williams Lehmann, The Basilica Aemilia and S. Biagio at Montepulciano, The Art Bulletin Vol. 64, No. 1 (Mar., 1982), pp. 124-131]. |

||||

| Pienza |

||||

| The monumental center of Pienza is the Piazza Pio II, living example of the utopian ideal city designed by humanists architects of the fifteenth century. The square contains all the main buildings of the village, the Cathedral, the Bishop's Palace, the Palazzo Piccolomini, Municipal Palace, the Palazzo Ammannati and a fine 15th century well. The highlight of the square is the facade of the Cathedral of the Assunta, that was built between 1459 and 1462. While the rest of the building is in tufa, the facade is in travertine with a double order of columns and three portals. In the great tympanum is the coat of arms of Pio II. The inside is with three aisles and contains five tables of the 15th century senese artists of an altar attributed to Bernardo Rossellino. To right of the Cathedral is Palazzo Piccolomini, the more important palace of Pienza, masterpiece of Bernardo Rossellino, it was built between 1459 and 1462. It represents a copy of Palazzo Rucellai in Florence planned from the same Rossellino, it has a square plan, flat ashlar-work with pillars of Tuscany order and two floors of double mullioned windows. Inside of the palace there is a beautiful square courtyard with loggia and a garden with beautiful panorama on the Val d' Orcia. To an angle of the palace it's the 15th century well with two columns with capitels. To the left of the Cathedral is the Episcopal Palace or Borgia, that it has two floors of Guelph windows and was restructured from the cardinal Rodrigo Borgia (future Pope Alexander VI). On the opposite side of the square in comparison to the Cathedral are the Communal Palace (with porch of ionic order, with a floor to four double mullioned windows and a beautiful tower finished in 1599) and Palazzo Ammannati. The Pieve of Corsignano (parish church), just outside of Pienza (less than 1 km) is one of the most important Romanesque monuments of the area. Piccolomini garden |

||||

| Designed in the second half of the 15th century together with the papal palace, of which it is an integral part, this garden was commissioned by Pope Pius II (Enea Silvio Piccolomini) to Bernardo Rossellino. The small terraced area dominates the entire Val d'Orcia (the "Orcia Valley"), and despite recent alterations still displays the typical features of the Renaissance garden.

|

||||

|

||||

Villa Arceno gardens |

Abbey of Sant 'Antimo |

Sovicille |

||