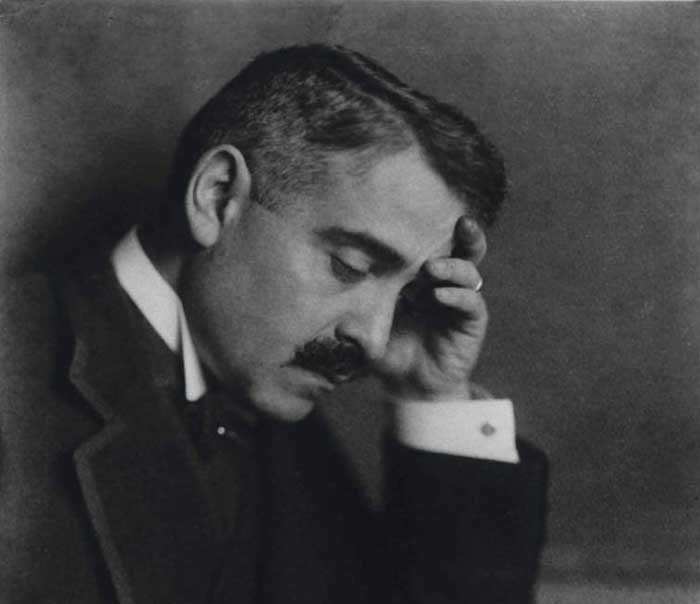

Aby Moritz Warburg (June 13, 1866 – October 26, 1929), was a German art historian and cultural theorist who founded a private Library for Cultural Studies, the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, which was later moved to the Warburg Institute, London. At the heart of his research was the legacy of the Classical World, and the transmission of classical representation, in the most varied areas of western culture through to the Renaissance.

Warburg described himself as: "Amburghese di cuore, ebreo di sangue, d'anima Fiorentino"[1] ("Hamburger at heart, Jew by blood, Florentine in spirit").

In 1886 Warburg began his study of art history, history and archaeology in Bonn and attended the lectures on the history of religion by Hermann Usener, those on cultural history by Karl Lamprecht and on art history by Carl Justi. He continued his studies in Munich and with Hubert Janitschek in Strasbourg, completing under him his dissertation on Botticelli's paintings The Birth of Venus and Primavera.

From 1888 to 1889 he studied the sources of these pictures at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence. He was now interested in applying the methods of natural science to the human sciences. The dissertation was completed in 1892 and printed in 1893. Warburg's study introduced into art history a new method, that of iconography or iconology, later developed by Erwin Panofsky. After receiving his doctorate Warburg studied for two semesters at the Medical Faculty of the University of Berlin, where he attended lectures on psychology. During this period he undertook a further trip to Florence.

In 1897 Warburg married, against his father's will, the painter and sculptor Mary Hertz, daughter of Adolph Ferdinand Hertz, a Hamburg senator and member of the Synod of the Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Hamburg, and Maria Gossler, both members of the traditional Hanseatic elite of Hamburg. The couple had three children: Marietta (1899–1973), Max Adolph (1902–1974) and Frede C. Warburg (1904–2004). In 1898 Warburg and his wife took up residence in Florence. While Warburg was repeatedly plagued by depression, the couple enjoyed a lively social life. Among their Florentine circle could be counted the sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand, the writer Isolde Kurz, the English architect and antiquary Herbert Horne, the Dutch Germanist André Jolles and his wife Mathilde Wolff-Mönckeberg, and the Belgian art historian Jacques Mesnil. The most famous Renaissance specialist of the time, the American Bernard Berenson, was likewise in Florence at this period. Warburg, for his part, renounced all sentimental aestheticism, and in his writings criticised a vulgarised idealisation of an individualism that had been imputed to the Renaissance in the work of Jacob Burckhardt.

Florence

During his years in Florence Warburg investigated the living conditions and business transactions of Renaissance artists and their patrons as well as, more specifically, the economic situation in the Florence of the early Renaissance and the problems of the transition from the Middle Ages to the early Renaissance. A further product of his Florentine period was his series of lectures on Leonardo da Vinci, held in 1899 at the Kunsthalle in Hamburg. In his lectures he discussed Leonardo's study of medieval bestiaries as well as his engagement with the classical theory of proportion of Vitruvius. He also occupied himself with Botticelli's engagement with the Ancients evident in the representation of the clothing of figures. Feminine clothing takes on a symbolic meaning in Warburg's famous essay, inspired by discussions with Jolles, on the nymphs and the figure of the Virgin in Domenico Ghirlandaio’s fresco in Santa Maria Novella in Florence. The contrast evident in the painting between the constricting dress of the matrons and the lightly dressed, quick-footed figure on the far right serves as an illustration of the virulent discussion around 1900 concerning the liberation of female clothing from the standards of propriety imposed by a reactionary bourgeoisie.

In 1902 the family returned to Hamburg, and Warburg presented the findings of his Florentine research in a series of lectures.

Warburg died in Hamburg of a heart attack on 26 October 1929.

Last project: Mnemosyne Atlas

In December 1927, Warburg started to compose a work in the form of a picture atlas named Mnemosyne. It consisted of 40 wooden panels covered with black cloth, on which were pinned nearly 1,000 pictures from books, magazines, newspaper and other daily life sources.[4] These pictures were arranged according to different themes: Coordinates of memory, Astrology and mythology, Archaeological models, Migrations of the ancient gods, Vehicles of tradition, Irruption of antiquity, Dionysiac formulae of emotions, Nike and Fortuna, From the Muses to Manet, Dürer: the gods go North, The age of Neptune, "Art officiel" and the baroque, Re-emergence of antiquity, The classical tradition today.[3]

There were no captions and only a few texts in the atlas. "Warburg certainly hoped that the beholder would respond with the same intensity to the images of passion or of suffering, of mental confusion or of serenity, as he had done in his work."[2] Mnemosyne Atlas was left unfinished when Warburg died in 1929.

In 1933 the Warburg collection was moved to London, where it became incorporated into the University of London in 1944.

|

The Institute is named after its founder Aby Warburg (1866-1929) [4]. Born in Hamburg, Warburg studied the history of art in Bonn, Florence and Strasbourg before graduating with a doctoral thesis on Botticelli's mythologies. Following Jakob Burckhardt, he came increasingly to feel the limitations of a predominantly stylistic approach to the history of art, and sought contact with the emerging Kulturwissenschaft of the anthropologists. The years succeeding his graduation were devoted to research in the archives of Florence, so as to build up a detailed picture of the intellectual and social milieu of Lorenzo de' Medici's circle. From this inquiry, Warburg was led to ask what the Florentines of his chosen period saw in antiquity, and why symbols created in a pagan context reappeared with renewed vitality in fifteenth-century Italy. Thus he conceived the programme of illustrating the processes by which the memory of the past affects a culture. The paradigm he chose was the influence of antiquity on modern European civilization in all its aspects – social, political, religious, scientific, philosophical, literary and artistic – and he ordered his private library in Hamburg accordingly.

In 1913 Warburg was joined by Fritz Saxl (1890-1948) who, in 1921, turned the library into a research institute. The further development of the Institute, especially after Warburg's death in 1929, was guided by Saxl, whose interests ranged over the history of art and religion, from the study of Mithraic monuments and astrological manuscripts to Rembrandt and Velázquez. Like Warburg, Saxl taught at the University of Hamburg where Erwin Panofsky and Ernst Cassirer, were his colleagues. The publications which appeared under his editorship show how large was the circle of scholars whom he attracted and who helped to shape the Institute's outlook and traditions.

One of Warburg's and Saxl's last and unaccomplished projects was the Mnemosyne Atlas

After the rise of the Nazi régime, Saxl accepted the invitation of an adhoc committee to transfer the Institute to London where, with the support of Lord Lee of Fareham, Samuel Courtauld and the Warburg family, it was installed in Thames House in 1934, moving to the Imperial Institute Buildings, South Kensington, in 1937. In 1944 the Institute was incorporated in the University of London. In 1994 it became a founder-member of the University's School of Advanced Study.

Saxl was succeeded as Director by Henri Frankfort (1897-1954), whose interest in the links between religion and social organization in the Ancient Near East extended the Institute's range. He was followed in 1955 by Gertrud Bing (1892-1964), whose career at the Institute had begun in 1922. Under her Directorship the Institute moved into its permanent home in a new building on the University site in 1958. From 1959 to 1976 Sir Ernst H. Gombrich O.M. (1909-2001) was Director, from 1976 to 1990, J. B. Trapp, from 1991 to 2001, Nicholas Mann.

Recent directors have been Charles Hope (2001 to 2010),[3] Peter Mack (2010 to 2014)[7] and David Freedberg (from July 2015 to April 2017).

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()