|

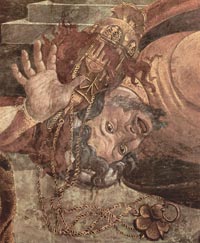

Sandro Botticelli, The Punishment of Korah and the Stoning of Moses and Aaron (detail), 1481-82, fresco, Cappella Sistina, Vatican

|

Sandro Botticelli | Frescoes in the Sistine Chapel

|

The Sistine Chapel is the best-known chapel in the Apostolic Palace, the official residence of the Pope in Vatican City. It is famous for its architecture, evocative of Solomon's Temple of the Old Testament, and its decoration which has been frescoed throughout by the greatest Renaissance artists including Michelangelo, Raphael, Bernini, and Sandro Botticelli. |

Scenes from the Life of Moses |

||

|

||

Sandro Botticelli, The Trials and Calling of Moses, 1481-82, fresco, 348,5 x 558 cm, Cappella Sistina, Vatican

|

||

| The Scenes from the Life of Moses fresco is opposite The Temptation of Christ also painted by Botticelli. The two pictures are typologically related in that both deal with the theme of temptation. Botticelli integrated seven episodes from the life of the young Moses into the landscape with considerable skill, by opening up the surface of the picture with four diagonal rows of figures. As the Moses cycle starts on the wall behind the altar, the scenes should, unlike the pictures of the temptations of Christ, be read from right to left: (1) Moses in a shining yellow garment, angrily strikes an Egyptian overseer and then (2) flees to the Midianites. There (3) he disperses a group of shepherds who were preventing the daughters of Jethro from (4) drawing water at the well. After (5,6) the divine revelation in the burning bush at the top left, Moses obeys God commandment and (7) leads the people of Israel in a triumphal procession from slavery in Egypt. |

|

|

| The central scene, in which Moses watering the sheep belonging to Jethro's daughters - one of them, Zipporah, later became his wife - is one of the most charming genre pictures in the entire cycle. According to the typologial interpretation, it is a reference to Christ, who looks after his Church. |

||

| As it was such an important event, Botticelli depicted the calling of Moses in two scenes. While Moses is looking after the sheep belonging to his stepfather, God appears to him in the burning bush and orders him to take off his shoes before approaching. Then he commands him to lead the children of Israel from Egypt into the Promised Land. | ||

The Punishment of Korah |

||

|

||

Sandro Botticelli, The Punishment of Korah and the Stoning of Moses and Aaron, 1481-82, fresco, Cappella Sistina, Vatican |

||

| The depicted scenes on the left wall are Moses's Testament by Luca Signorelli and The Punishment of Korah by Sandro Botticelli. The message of The Punishment of Korah provides the key to an understanding of the Sistine Chapel as a whole before Michelangelo's work. The fresco, located in the fifth compartment on the south wall, reproduces three episodes, each of which depicts a rebellion by the Hebrews against God's appointed leaders, Moses and Aaron, along with the ensuing divine punishment of the agitators. On the right-hand side, the revolt of the Jews against Moses is related, the latter portrayed as an old man with a long white beard, clothed in a yellow robe and an olive-green cloak. Irritated by the various trials through which their emigration from Egypt was putting them, the Jews demanded that Moses be dismissed. They wanted a new leader, one who would take them back to Egypt, and they threatened to stone Moses; however, Joshua placed himself protectively between them and their would-be victim, as depicted in Botticelli's painting. The centre of the fresco shows the rebellion, under the leadership of Korah, of the sons of Aaron and some Levites, who, setting themselves up in defiance of Aaron's authority as high priest, also offered up incense. In the background we see Aaron in a blue robe, swinging his incense censer with an upright posture and filled with solemn dignity, while his rivals stagger and fall to the ground with their censers at God's behest. Their punishment ensues on the left-hand side of the picture, as the rebels are swallowed up by the earth, which is breaking open under them. The two innocent sons of Korah, the ringleader of the rebels, appear floating on a cloud, exempted from the divine punishment. The principal message of these scenes is made manifest by the inscription in the central field of the triumphal arch: "Let no man take the honour to himself except he that is called by God, as Aaron was." The fresco thus holds a warning that God's punishment will fall upon those who oppose God's appointed leaders. This warning also contained a contemporary political reference through the portrayal of Aaron in the fresco, depicted wearing the triple-ringed tiara of the Pope and thus characterized as the papal predecessor. It was a warning to those questioning the ultimate authority of the Pope over the Church. The papal claims to leadership were God-given, their origin lay in Christ giving Peter the keys to the kingdom of heaven and thereby granting him privacy over the young Church. Perugino painted this crucial element of the doctrine of papal supremacy immediately opposite Botticelli's fresco. |

||

| In the central scene Aaron's sons and the sons of Levi are sacrificing in competition with him; Aaron himself is dressed in blue robes and is wearing a blue and gold hat which is similar to the papal tiara. Struck by their censers, they are being forced to the ground by the power of God, called on by Moses.

The principal message of the scenes depicted in the fresco is made manifest by the inscription in the central field of the triumphal arch: "Let no man take the honour to himself except he that is called by God, as Aaron was." The fresco thus holds a warning that God's punishment will fall upon those who oppose God's appointed leaders. Apart from the different inscription and less lavish decoration, the triumphal arch is an almost exact copy of the Roman Arch of Constantine. |

||

| On the right-hand side of the fresco, the revolt of the Jews against Moses is related, the latter portrayed as an old man with a long white beard, clothed in a yellow robe and an olive-green cloak. Irritated by the various trials through which their emigration from Egypt was putting them, the Jews demanded that Moses be dismissed. They wanted a new leader, one who would take them back to Egypt, and they threatened to stone Moses; however, Joshua placed himself protectively between them and their would-be victim, as depicted in Botticelli's painting.

The classical ruins in the background, while still largely visible in Botticelli's day, are completely destroyed nowadays. They constitute the remains of a backdrop for waterworks which had been constructed by Emperor Septimius Severus within the bath complex on the Palatine Hill. |

|

|

The Temptation of Christ |

||

|

||

Sandro Botticelli, Three Temptations of Christ, 1481-82, fresco, 345 x 555 cm, Cappella Sistina, Vatican |

||

| The fresco which Botticelli began in July 1481, is the third scene within the Christ cycle and depicts the Temptation of Christ. Christ's threefold temptation by the Devil, as described in the Gospel according to Matthew, can be seen in the background of the picture, with the devil disguised as a hermit. At top left, up on the mountain, he is challenging Christ to turn stones into bread; in the centre, we see the two standing on a temple, with the Devil attempting to persuade Christ to cast himself down; on the right-hand side, he is showing the Son of God the splendour of the world's riches, over which he is offering to make Him master. However, Christ drives away the Devil, who ultimately reveals his true devilish form. On the right in the background, three angels have prepared a table for the celebration of the Eucharist, a scene that becomes comprehensible only when seen in conjunction with the event in the foreground of the fresco. The unity of these two events from the point of view of content is clarified by the reappearance of Christ with three angels in the middle ground on the left of the picture, where he is, it is apparent, explaining the incident occurring in the foreground to the heavenly messengers. We are concerned here with the celebration of a Jewish sacrifice, conducted daily before the Temple in accordance with ancient custom. The high priest is receiving the blood-filled sacrificial bowl, while several people are bringing animals and wood as offerings. At first sight, the inclusion of this Jewish sacrificial scene in the Christ cycle would appear extremely puzzling; however,its explanation may be found in the typological interpretation. The Jewish sacrifice portrayed here refers to the crucifixion of Christ, who through His death offered of His flesh and blood for the redemption of mankind. Christ's sacrifice is reconstructed in the celebration of the Eucharist, alluded to here by the gift table prepared by the angels. Christ's threefold temptation by the Devil, as described in the Gospel according to Matthew, can be seen in the background of the picture, with the devil disguised as a hermit. At top left, up on the mountain, he is challenging Christ to turn stones into bread. |

|

|

| Among the crowd of people making up the Jewish sacrificial scene, a woman in the left-hand foreground who is carrying on her head a bowl with hens in it strikes us familiar. This figure is a copy of Abra, the maid in the small panel of The Return of Judith to Bethulia, which Botticelli had painted a decade before. The posture of the woman carrying wood in the right-hand foreground (this picture) may also be derived from this picture. These similarities lead to the assumption that Botticelli kept sketches of his compositions and figures so to have a stock of motifs upon which he could then draw his later pictorial creations. In contrast, Botticelli borrowed the small boy holding bunches of grape, and who has been frightened by a snake, from Hellenistic sculpture. |

|

|

| The fresco represents Christ's threefold temptation by the Devil. In the centre, we see Christ and the Devil standing on a temple, with the Devil attempting to persuade Christ to cast himself down. |

|

|

| On the right-hand side, he is showing the Son of God the splendour of the world's riches, over which he is offering to make Him master. However, Christ drives away the Devil, who ultimately reveals his true devilish form. |

|

|

Saint Sixtus II |

||

|

||

St Sixtus II, 1481, fresco, 210 x 80 cm, Cappella Sistina, Vatican |

||

| Originally, in the register above the history paintings, the decoration of the Sistine Chapel consisted of twenty-eight portraits of early popes who had died as martyrs. (Four of them, the portraits of the first four popes on the altar wall, have not survived). The two rows of popes do not appear in chronological order, the sequence moves back and forth between the north and south wall to form a zigzag pattern. It is assumed that the papal portraits were executed by the assistants of the four masters (Botticelli, Perugino, Ghirlandaio and Rosselli) entered into contract for the decoration. However, it is possible to identify specific stylistic features in many of the portraits, and it therefore appears that Botticelli designed an unusually large share of them, seven portraits including that of Sixtus II.

The portraits of the popes are imaginary. As can be seen in the figure of Sixtus II, a namesake of the pope who commissioned the work, they are full length figures placed in niches and painted, so as to be seen from far below, high up on the walls of the room. All popes are shown wearing pontifical robes and the tiara. |

||

|

Virtual Visit of the Sistine Chapel | www.vatican.va |

| The Vatican Museums The Vatican Museums contain a vast store of artworks which range from the ancient to the contemporary, including the world famous Sistine Chapel. Touring the Vatican Museums can easily take two hours or more, so it is imperative that you have an action plan when you visit. Here is a list of the top attractions to look for when you visit the Vatican Museums. For a complete list, visit the Vatican Museums website. 1. The Sistine Chapel The Sistine Chapel is one of the main attractions to visit in Vatican City. The highlight of a visit to the Vatican Museums, the famous chapel contains ceiling and altar frescoes by Michelangelo and is considered one of the artist's greatest achievements. But the chapel contains more than just works by Michelangelo; it is decorated from floor to ceiling by some of the most famous names in Renaissance painting. The Sistine Chapel is the last room that visitors see when touring the Vatican Museums. The grand chapel that is known around the world as the Sistine Chapel was built from 1475-1481 at the behest of Pope Sixtus IV (the Latin name Sixtus, or Sisto (Italian), lending its name to "Sistine"). The monumental room measures 40.23 meters long by 13.40 meters wide (134 by 44 feet) and reaches 20.7 meters (about 67.9 feet) above the ground at its highest point. The floor is inlaid with polychrome marble and the room contains an altar, a small choristers' gallery, and a six-paneled marble screen that divides the room into areas for clergy and congregants. There are eight windows lining the upper reaches of the walls. Michelangelo's frescoes on the ceiling and the altar are the most famous paintings in the Sistine Chapel. Pope Julius II commissioned the master artist to paint these parts of the chapel in 1508, some 25 years after the walls had been painted by the likes of Sandro Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Pinturrichio, and others. 2. The Raphael Rooms The four Stanze di Raffaello ("Raphael's rooms") in the Palace of the Vatican form a suite of reception rooms, the public part of the papal apartments. They are famous for their frescoes, painted by Raphael and his workshop. Together with Michelangelo's ceiling frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, they are the grand fresco sequences that mark the High Renaissance in Rome. The Stanze, as they are invariably called, were originally intended as a suite of apartments for Pope Julius II. He commissioned Raphael, then a relatively young artist from Urbino, and his studio in 1508 or 1509 to redecorate the existing interiors of the rooms entirely. It was possibly Julius' intent to outshine the apartments of his predecessor (and rival) Pope Alexander VI, as the Stanze are directly above Alexander's Borgia Apartment. They are on the third floor, overlooking the south side of the Belvedere Courtyard. 3. The Borgia Apartments The artist Pinturicchio painted the rich frescoes in the Borgia Apartments, the area on the first floor where Pope Alexander VI lived. The rich, colorful frescoes depict scenes from Egyptian and Greek mythology and speak to lavishness of the Vatican Palace. The Borgia Apartment was a private wing built for Alexander VI (1492-1503) and decorated by Bernardo di Betto, called il Pinturicchio and his assistants. After the pontiff’s death, the work on the apartments stopped. They were only re-opened to the public at the end of the 19th century. Most of the rooms are now used for the Collection of Modern Religious Art, inaugurated by Paul VI in 1973. This Collection hosts about 600 accumulated works of painting, sculpture and graphic, through donations of contemporary Italian and foreign artists and includes works by Gaugin, Chagall, Klee and Kandinskij. 4. The Gallery of Maps When the Renaissance Pope Gregory XIII (1572-85) decided to commemorate a spacious Vatican gallery, he commissioned the Dominican friar and cosmographer Egnizio Danti. In conscious imitation of the ancient Roman custom of decorating the walls of state buildings with geographical images, Danti designed 40 richly embellished maps of Italian port cities in two parallel lines along the walls. This incredible hall has maps frescoed on both walls showing various parts of Italy from the 16th century. These historically significant frescoes of the Italian cities, the countryside, and geographical features, such as the Apennine Mountains and the Tyrrhenian Sea, are a joy to inspect, as is the gallery's sumptuously decorated coffered ceiling. 5. The Cappella Nicolina Named for Pope Nicholas V, who worshipped here, this chapel is located in one of the oldest parts of the papal palace. In 1447, or perhaps earlier, Fra Angelico was in Rome, where he painted the private chapel of Pope Nicholas V with scenes from the lives of St Lawrence and St Stephen, frescoes which sum up the whole trend of his work. They possess a logical realism in their perspective settings, clarity of scale and narrative content, and restraint in their vigour. The colour is limpid, but with sufficient use of chiaroscuro to give substance to the figures; the use of continuous representation is kept to a minimum by the division of the scenes through differences in their architectural setting, but nowhere is the search for realism in the use of lighting effects allowed to destroy the unity of the whole, or the sense of the plane of the wall. Fra Angelico | Frescoes in the Cappella Niccolina of the Palazzi Pontifici in Vatican (1447-49) 6. Greek and Roman Antiquities The Pio-Clementine and the Gregorian Profane Museums are dedicated to treasures of antiquity. Highlights include the Apollo del Belvedere, "a supreme ideal" of classical art; the Laocoön, a large marble composition from 1st century A.D.; the Belvedere Torso, a Greek sculpture from the 1st century B.C.; the Discus Thrower, a 5th century B.C. representation of an discus athlete in movement; and a collection of Roman mosaics. |

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Sandro Botticelli and Sistine Chapel, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

|

|

Podere Santa Pia, morning view on the Maremma from the northern terrace

Podere Santa Pia is an old farm that has been renovated into a perfect holiday house located 350 meters above sea level in a panoramic position. The valley below is characterized by all the elements of the Tuscan landscape: vineyards, pastures, small forests, wheat fields, olive groves and downey oaks. To the south is the little isle of Montecristo, and on a clear day you can see as far as Corsica. |