|

|

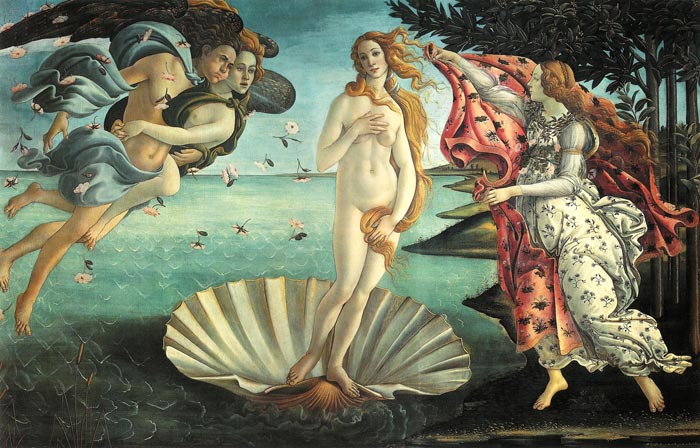

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, c. 1486, Uffizi Gallery, Florence |

|

Sandro Botticelli | The Birth of Venus |

The Birth of Venus or Nascita di Venere is a painting by Sandro Botticelli. It depicts the goddess Venus, having emerged from the sea as a full grown woman, arriving at the sea-shore (which is related to the Venus Anadyomene motif). The painting is held in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

But more than a rediscovered Homeric hymn was likely in the mind of the Medici family member who commissioned this painting from Botticelli. The painter and the humanist scholars who probably advised him would have recalled that Pliny the Elder had mentioned a lost masterpiece of the celebrated artist, Apelles, representing Venus Anadyomene (Venus Rising from the Sea). According to Pliny, Alexander the Great offered his mistress, Pankaspe, as the model for the nude Venus and later, realizing that Apelles had fallen in love with the girl, gave her to the artist in a gesture of extreme magnanimity. Pliny went on to note that Apelles' painting of Pankaspe as Venus was later "dedicated by Augustus in the shrine of his father Caesar." Pliny also stated that "the lower part of the painting was damaged, and it was impossible to find anyone who could restore it. . . . This picture decayed from age and rottenness, and Nero. . .substituted for it another painting by the hand of Dorotheus".

|

||

|

||

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, (detail), c. 1486, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

|

||

Classical inspiration |

||

| The central figure of Venus in the painting is very similar to Praxiteles' sculpture of Aphrodite. The version of her birth, is where she arises from the sea foam, already a full woman. In classical antiquity, the sea shell was a metaphor for a woman's vulva.[16] The pose of Botticelli's Venus is reminiscent of the Venus de' Medici, a marble sculpture from classical antiquity in the Medici collection which Botticelli had opportunity to study. The Birth of Venus demonstrates the fascination of Renaissance artists with Greek mythological subjects. Not only is the central figure of the scene Venus, but she is shown in the "Venus pudica" pose of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. The Aphrodite of Cnidus (Knidos) by Praxiteles (c.350 BC) is the first monumental female nude in classical sculpture. It is the Capitoline Venus, however, where both the breasts and pubis are self-consciously covered, that is the archetype of so many representations of the female nude that follow, including Masaccio's The Expulsion and Botticelli's The Birth of Venus. This is the pose of the Venus Pudica or modest Venus, in which the arms envelope a body that is both sensuous and distant. |

||

|

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, (detail), c. 1486, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

|

[1] At the height of his fame, the Florentine painter and draughtsman Sandro Botticelli was one of the most esteemed artists in Italy. His graceful pictures of the Madonna and Child, his altarpieces and his life-size mythological paintings, such as 'Venus and Mars', were immensely popular in his lifetime. |

| This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Sandro Botticelli and The Birth of Venus, published under the GNU Free Documentation License. |

Podere Santa Pia, a thoughtfully restored holiday rental house located on the edge of the nature reserve Poggio all'Olmo, in the foothills of the dramatic Monte Amiata, boasts stunning views over the Maremma countryside, as far as the sea and the Island of Monte Christo. .Even today the Maremma remains a largely undiscovered gem in the heart of Italy, sandwiched between the stunning Monte Amiata on its eastern fringes and the beautiful Tyrrhenian coast to the west. Italy's Tuscany region offers the visitor such a feast of culinary delights it really is difficult to know where to start. If you love great wines, great food and great scenery, this wonderful holiday house is the ideal base. Arcidosso has a very pretty market square full of life, lovely cafes and restaurants and is seen by many as the gateway to the spellbindingly beautiful Monte Amiata. The Val d'Orcia, a place where to admire both the enchanting landscapes and the picturesque towns of the Tuscan countryside, is within easy reach. For garden-lovers and those who just enjoy the iconic views of the Tuscan countryside, Villa La Foce is nearby. The villa, one of the great private gardens of Italy, lies on a hill overlooking the beautiful and unspoiled Val d'Orcia. Our manual will guide you. Holiday houses in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | | Residency in Tuscany for writers and artists |

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, view from the garden on the valley below |

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montecristo |

||

Monasterio San Bruzio |

Massa Marittima |

Campagnatico |

||

Il parco dei Mostri di Bomarzo |

Perugia

|

Florence, Duomo |

||

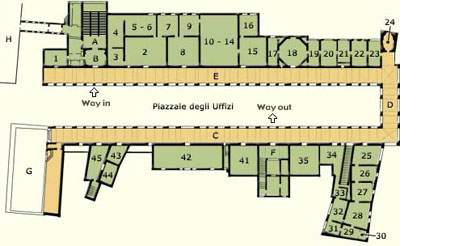

Galleria degli Uffizi

|

S E C O N D F L O O R

|

|||

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia, evening view on the Maremma from the northern terrace |

||||