| |

|

Piero della Francesca is now recognised as one of the great artists of the early Renaissance and yet by the time of his death in 1492 he was better known as a mathematician and geometer than as an artist. He had studied and absorbed the artistic discoveries of his great Florentine predecessors and contemporaries — Masaccio, Donatello, Domenico Veneziano, Filippo Lippi, Uccello, and even Masolino, who anticipated something of Piero's use of broad masses of colour. Piero unified, completed, and refined upon the discoveries these artists had made in the previous 20 years and created a style in which monumental, meditative grandeur and almost mathematical lucidity are combined with limpid beauty of colour and light.

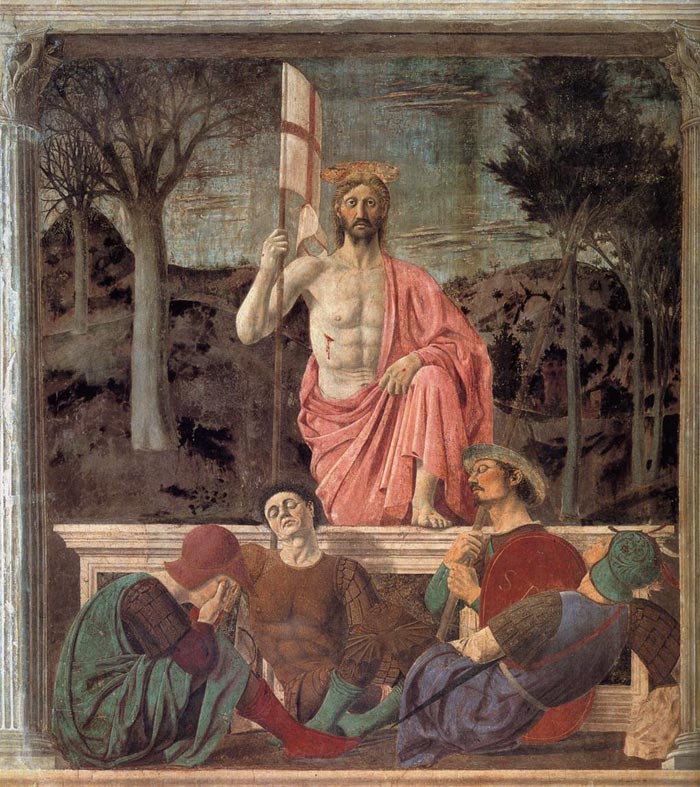

In 1467, Piero della Francesca was commissioned to paint a Resurrection which is now one of his most famous works. The fresco was painted in the Meeting Hall of Palazzo dei Conservatori di Sansepolcro, the current Civic Museum, probably in 1467-68.[2] The subject of the picture alludes to the name of the city (meaning Holy Sepulchre), derived from the presence of two relics of the Holy Sepulchre carried by two pilgrims in the 9th century. Christ is also present on the town's Coat of Arms.

It is likely that Piero painted his striking image of the risen Christ stepping resolutely, banner in hand, from the tomb, to represent not only the resurrection of Jesus but also the resurgence of Sansepolcro.

Jesus is in the centre of the composition, portrayed in the moment of his resurrection, as suggested by the position of the leg on the parapet. His figure, depicted in an iconic and abstract fixity (and described by Aldous Huxley as "athletic"), is hanging over four sleeping soldiers, representing the difference between the human and the divine spheres (or the death, defeated by Christ's light). The landscape, immersed in the dawn light, has also a symbolic value: the contrast between the flourishing trees on the right and the bare ones on the left alludes to the renovation of men through the Resurrection's light.

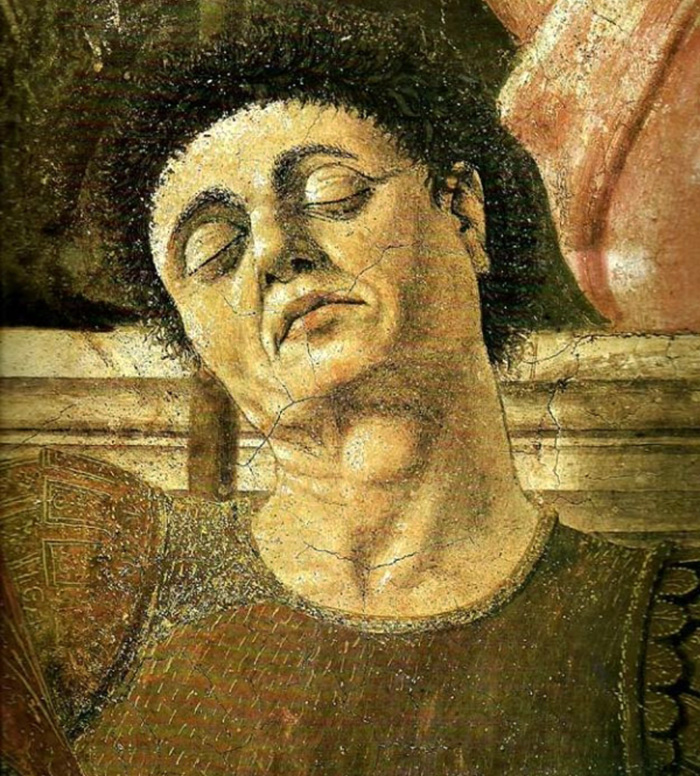

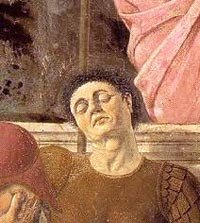

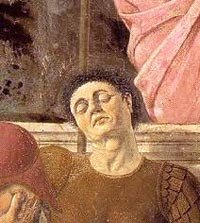

According to tradition, the sleeping soldier in brown armor on Christ's right is a self-portrait of Piero. The contact between his head and the pole of the Guelph banner carried by Christ is supposed to represent his contact with the divinity.

Aldous Huxley described The Resurrection as "the greatest painting in the world".[1]

|

|

|

|

| |

|

According to tradition, the sleeping soldier in brown armor on Christ's right is a self-portrait of Piero. The contact between his head and the pole of the Guelph banner carried by Christ is supposed to represent his contact with the divinity.

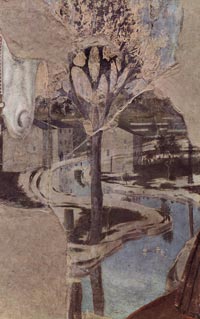

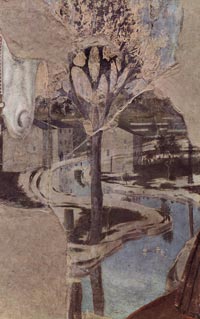

'One of the most interesting aspects of the works of Piero della Francesca, whether they are frescoes or panel paintings, is the landscape to which the artist devotes ample space in his works. Who has not paused for a moment to observe and submit to the attraction of those natural or architectural backgrounds which are to be found in the frescoes of the Legend of the True Cross in Arezzo or the Resurrection in Sansepolcro? The attraction that this aspect has always exerted, inspiring poets to pen noble verses and writers to impassioned prose, is well-known. Even today, the descriptions of the great travellers could guide the visitor through the works of Piero della Francesca, allowing him to discover that practically nothing has changed. The beautiful views, the daring foreshortenings, the barren and rocky mountains of the Valtiberina are those described in 1581 by Michel de Montaigne on a journey from Sansepolcro to Arezzo, via the La Scheggia pass, landscapes immortalised in the background to the Resurrection.

The Tiber, the river that laps the town of Sansepolcro and appears as a naturalistic element dividing the two armies in the Battle between Constantine and Maxentius in the Arezzo frescoes, is described with particular affection and devotion by the English writer G. M. Trevelyan: "This reach of the great river, where it first leaves its mountains cradle, has a peculiar effect on the imagination...the line of a poplar wood shading the course of the Tiber...a clear stream of the blue and silver eddies". The ilex-cloaked hills that form the background to the scene showing the Queen of Sheba appears to have been a landscape very dear to Piero, a memory linked to the artist's childhood between the Val Cerfone and the Val Padonchia, between which was the birthplace of his mother, Monterchi , famous for the celebrated fresco of the Madonna del Parto. The ploughed fields, the hills seen from the heights of Anghiari appearing like hillocks of colour, shifting with the change of the seasons, are arranged with graceful harmony and give the observer a sense of calm and grace. These are the same sensations that we perceive before the landscape of the Adoration of the Wood in the Arezzo cycle, or in the background of the Resurrection in Sansepolcro.'

|

|

Piero della Francesca, Battle between Constantine and Maxentius, (detail, Tiber) c. 1458, fresco, 322 x 764 cm, San Francesco, Arezzo Piero della Francesca, Battle between Constantine and Maxentius, (detail, Tiber) c. 1458, fresco, 322 x 764 cm, San Francesco, Arezzo

|

| |

|

|

|

Andrea del Castagno (1423-1457) was born in a village in the Mugello area near Florence now called Castagno d'Andrea, and was probably trained in Florence. He was well known for the emotional expressionism and naturalism of his figure style. Castagno's first noteworthy paintings were executed for the Florentine convent of Sant' Apollonia. In this fresco cycle of 1447 Castagno depicted scenes from the Passion of Christ and the Last Supper, works influenced by the pictorial illusionism of Masaccio.

The presence in Florence of Domenico Veneziano – who, assisted by Piero della Francesca, worked in the church of Sant'Egidio (1439-1445) – was probably decisive for Andrea. Even without giving credence to Vasari's story about Andrea's envy of Domenico, he was certainly influenced by the latter's clear, luminous palette and rigorous perspective constructions, with solutions often very near to or foreshadowing those of Piero della Francesca.

The obvious analogies between this fresco, the Resurrection, and the same subject painted several years later by Piero della Francesca in Borgo San Sepolcro has been the object of many critical studies. The simplicity and the perfect perspective composition of the fresco in Sant'Apollonia is considered by some scholars an anticipation of the art of Piero, whereas others think that it is rather a reflection of it.

|

|

Andrea del Castagno, Resurrection, 1447, fresco, Sant'Apollonia, Florence [3] |

| |

|

|

|

|

Andrea del Castagno, Resurrection (detail), 1447, fresco, Sant'Apollonia, Florence |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

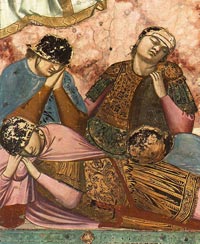

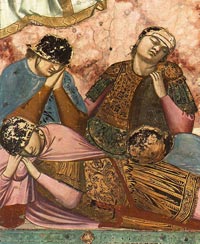

The cathedral in Sansepolcro contains a gilded polyptych of the Resurrection (14th century), attributed to Niccolo di Segna. The central figure of Christ stands in a pose so similar to Piero della Francesca's Ressurection in the Museo Civico, that many feel della Francesca must have studied this first.

Niccolo di Segna began his career in the workshop of his father, Segna di Buonaventura.

He followed the style of Duccio with a greater rigidity of the forms. He was also influenced by Simone Martini as seen in the Crucifixion (1345, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena) and in the frescoes attributed to him (S. Colomba a Monteriggioni near Siena).

Art in Tuscany | Niccolò di Segna

'In Piero's work the relationship between divinity and humanity is expressed with figurative solutions which are related either to a still Medieval type or portrayal, or to a "modus operandi" open to the new trends. In the central panel of the Polyprych of the Misericordia (see page 19), the figure of the Virgin is much bigger than the figures of the donors beneath her cloak.

This is entirely in keeping with the Medieval model that resolved the divine-human relationship in dimensional terms, as we can see in the two fourteenth century paintings shown here.

In the Resurrection, via Andrea del Castagno and Giotto - obviously - the determining model is Masaccio's Trinity. Here the relationship between divine and human is not resolved in terms of size, but rather by perspective. They can no longer be "framed" the same way. It is of little importance that Piero overturned Masaccio's perspective solutions. In the Resurrection it is the guards who are seen from below and Christ from the front; in the Trinity Christ and the saints are seen from below, and the patron from the front.' [3]

|

|

Resurrection by Niccolò di Segna

|

The Cappella degli Scrovegni in Padua (also known as the Arena Chapel) is regarded as one of the masterpieces of Western Art.

It was commissioned in 1300 by Enrico Scrovegni as penance for the sins of his father Reginaldo. It is known as the Arena Chapel as the site it is built on was that of a Roman arena. The building was completed in 1303 and Scrovegni commissioned Giotto to decorate the interior in fresco- a project completed around 1305.

The chapel is unornamented apart from Giotto's work with a barrel vault roof. Above the entrance is a Last Judgement by Giotto covering the entire wall that includes a devotional portrait of Enrico Scrovegni. On the side walls arranged in tiers 3 deep by four wide are fresco groups each scene being roughly 2 meters square. Facing the altar the sequence begins at the top of the right hand wall with scenes from the life of the Virgin with the annunciation of her mother and presentation at the temple. The series continues through the Nativity and Passion of Jesus, the Resurrection and the final scene Pentecost. The panels are noted for their emotional intensity, sculptural figures and naturalistic space. Between the main scenes Giotto used a faux architectural scheme of painted marble decorations and small recesses.

The observation of nature meant that set forms and symbolic gestures which in Medieval art, and particularly the Byzantine style prevalent in much of Italy, were used to convey meaning, were replaced by the representation of human emotion as displayed by a range of individuals.

In this Resurrection, Giotto shows the sleeping soldiers with faces hidden by helmets or foreshortened to emphasise the relaxed posture.

Art in Tuscany | Giotto di Bondone

|

|

Giotto di Bondone, Scenes from the Life of Christ, Resurrection (detail), Cappella degli Scrovegni all'Arena, Padua |

In the footsteps of Piero della Francesca

|

|

Itinerary in Tuscany| Starting from Sansepolcro, his hometown, follow this itinerary, and see his greatest work of Piero della Francesca in Sansepolcro, Perugia, Urbino, Arezzo, Rimini and eventually Florence.

Itinerary in Central Italy | In the footsteps of Piero della Francesca

|

|

|

[1] Sansepolcro escaped artillery fire during World War 2 because Antony Clarke, the British captain charged with the task, had read the aforementioned essay by Aldous Huxley which described The Resurrection as "the greatest painting in the world". Captain Clarke had never seen the painting but at the last moment (shelling had already begun) remembered where he had heard of Sansepolcro and ordered his men to stop. A message received later informed them that the Germans had already retreated from the area — the bombardment hadn't been necessary. The town, along with its famous painting, survived.

[2] In the late sixteenth century an altar was placed in front of the fresco, but it does not appear that originally the painting had any liturgical function. Only after the fresco had been painted were this and the adjacent room vaulted. According to Salmi (1975) this occurred around 1470. Battisti (1971, 11, p. 34) believes that the construction of the partition in the room below was needed to sustain the weight of the vaults that had been (or were just about to be) added on the floor above. The room, on the first floor of the Residenza, where the offices of the commune were, does not seem to have been the assembly room (1. Borri Cristelli, 1989). Bombe (1909) attributed a function of civic representation to the picture, even though it was only much later that the Resurrection was adopted as the emblem of the city. Since the sixteenth century the seal of the commune contained the image of the Resurrection with the words: 'sub umbra alarum tuarum protcgc nos' (A. Mariucci, 'Lo stemma della città di Borgo Sansepolcro e la "Resurrezione di Piero della Francesca"', in Alta Val/e del Tevere, 1,4, 1933, pp. 17-20 quoted by E. Battisti).

Carlo Bertelli, Piero della Francesca, New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 1992, p. 198.

[3] Marco Bussagli, Piero Della Francesca, p. 24, Giunti Editore, 2007

Butcher, Tim (24 December 2011). "The man who saved The Resurrection". BBC News. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

BBBC News - The man who saved The Resurrection | www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-16306893

Sansepolcro was spared much damage during World War 2 when British artillery officer Tony Clarke defied orders and held back from using his troop's guns to shell the town.

The Private Life of a Masterpiece, episode 22 | Piero della Francesca, The Resurrection

Film in Toscana | Arezzo, Sansepolcro and Monterchi, the homeland of Piero della Francesca

Famous texts | Aldous Huxley, The Best Picture”

|

|

Piero della Francesca, The Resurrection (self-portrait, detail of fresco), Museo Civico of Sansepolcro Piero della Francesca, The Resurrection (self-portrait, detail of fresco), Museo Civico of Sansepolcro

Piero della Francesca - Resurrezione nel 2018, dopo il restauro.

|

|

|

|

![]()

Piero della Francesca, The Resurrection (self-portrait, detail of fresco), Museo Civico of Sansepolcro

Piero della Francesca, The Resurrection (self-portrait, detail of fresco), Museo Civico of Sansepolcro