| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| I T |

Piero della Francesca, Saint Michael, completed 1469, The National Gallery, London |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca | Polyptych of Saint Augustine (1460-1470)

|

|

|

|

| |

|

In 1454 Angelo di Giovanni di Simone d’Angelo ordered from Piero a polyptych for the high altar of S. Agostino in Borgo Sansepolcro. The commission specified that this work, undertaken to fulfill the wish of Angelo’s late brother Simone and the latter’s wife Giovanna for the spiritual benefit of the donors and their forebears, was to consist of several panels with “images, figures, pictures, and ornaments.” The central portion of the altarpiece is lost, but four lateral panels with standing saints, St. Michael the Archangel (National Gallery, London), St. Augustine (Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon), St. Nicholas of Tolentino (Museo Poldi-Pezzoli, Milan), and the present panel have survived.

The polyptych is now divided between various museums and part of it has been lost. The temptation to reconstruct the polyptych remains strong.[1] On pictorial grounds the following panels, placed from left to right, are associated with it:

Saint Augustine, Lisbon, Museo de Arte Antiga, 132 by 56.5cm.

Saint Michael the Archangel, London, National Gallery, 133 by 59.5 cm.

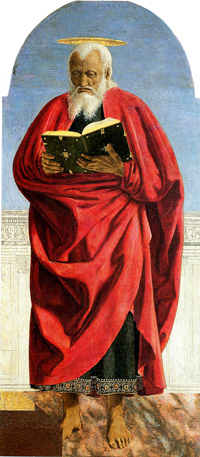

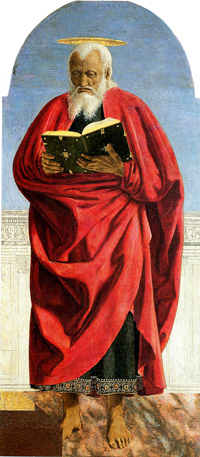

Saint John the Evangelist, New York, Frick Collection, 13 I. 5 by 57.8 cm.

Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli, 136 by 59 cm. Oil and tempera on panel

Among the many works that, according to Vasari, Piero painted in Perugia, the historian describes with great admiration the polyptych commissioned by the nuns of the convent of Sant'Antonio da Padova. This complex painting, today in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Perugia, was begun shortly after Piero's return from Rome, but was not completed for several years.

|

|

Possible reconstruction

|

The central part of the composition, the Madonna and Child with Saints Anthony, John the Baptist, Francis and Elisabeth, reveals in its unusual damask-like background the artist's aquaintance with a trend of contemporary Spanish painting, which Piero would have had the opportunity to see in Rome. We can therefore date the panel at around 1460. The polyptych is also made up of three predella panels showing St Anthony of Padua resurrecting a child, the Stigmatization of St Francis and St Elisabeth saving a boy who had fallen down a well, as well as two roundels placed between the main panel and the predella. The quality of this predella is extraordinary: Piero's characteristic spatial and light values are achieved here, on a small scale, by emphasizing the white walls of the interiors, the splashes of light and the deep shadows of the night scene in the open countryside. These scenes, where the bodies and even the shadows are fully three-dimensional, were to set an example for predella panels which was widely followed by Italian artists of the second half of the 15th-century, from the young Perugino to Bartolomeo della Gatta and, via Antonello da Messina, to the Neapolitan 'Master of Saints Severino and Sossio'. A few years later, Piero della Francesca completed the Perugia polyptych: above the ornate and still basically Gothic frame, he painted his extraordinary Annunciation.

The lack of compositional unity with the central part of the polyptych has led some scholars to suggest that Piero simply added this Annunciation to the altarpiece, much later.

According to others, the whole polyptych has a structural unity; Piero simply cut out the top part, originally intended to be rectangular, and transformed it into a sort of cusped crowning. Once again Piero has succeeded in overcoming the limitations imposed by patrons with old-fashioned artistic taste, giving us one of the most perfect examples of his use of perspective. Thanks also to his use of oil paints, Piero della Francesca achieves the extraordinarily detailed depiction of the series of capitals, running towards the vanishing point. Each architrave, and each column as well, projects a thin strip of shadow into the splendid cloister arcade, which appears to go beyond any inspiration derived from Alberti's architecture. The subtle analysis of the decorations painted on the walls reaches an unprecedented level; yet everything is contained in a single and organic space. Distances, so perfectly calculated, are neither forced nor artificial: they are conveyed by the realistic light and atmosphere. |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

St Augustine, portrayed with a mitre and a splendid bishop's cope is one of the high points of Piero's painting, for here he achieves perfect harmony between the imposing solidity of his three-dimensional forms and his miniaturistic attention to detail. Since the art of Gentile da Fabriano, no Italian painter had succeded in giving such a detailed reproduction of a saint's vestments. [4] Piero paints every single scene depicted on this precious cope as though he were painting a small predella panel, using, for the soft decorations of the fabric, a "dot" technique worthy of a miniature by Fouquet. And yet, it is the monumental values that prevail in the figure of this austere saint.

Archangel Michael is portrayed as an ancient warrior, his athletic limbs made more elegant by his precious armour, by the graceful tunic and by his beautiful boots decorated by with tiny pearls. There is nothing violent nor dramatic in the killing of the dragon, who is shown as a snake, its decapitated body lying on the ground. |

|

Piero della Francesca, Saint Augustine, (c. 1465), Lisbona, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga |

|

| |

|

|

|

The panels on the right represent St John the Evangelist (132 x 58 cm, Frick Collection, New York), and St Nicholas of Tolentino (133 x 60 cm, Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan).

"Although the venerable figure in the Frick painting was given no identifying attributes, he is presumed to represent St. John the Evangelist, patron of the donors’ father and of Simone’s wife. Evidence from a payment made to Piero in 1469 suggests that the altarpiece was finished late that year, fifteen years after the original contract. The lengthy delay resulted no doubt from Piero's many other commitments during this period, when he traveled to towns all across Central Italy and contracted obligations to patrons more important and more exigent than the family of Angelo di Giovanni and the Augustinian monks of his own small town, Borgo Sansepolcro. But it is obvious as well from the character of his art that Piero was not a quick or facile painter. His deep interest in the theoretical study of perspective and geometry and his pondered, contemplative approach to his paintings are apparent in all his work, including the panels of the S. Agostino altarpiece." [2] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| It has been proposed that this Crucifixion, like two panels also in The Frick Collection portraying an Augustinian monk and nun, originally formed a part of Piero’s S. Agostino altarpiece. The first known reference to The Crucifixion is found in a seventeenth-century document listing paintings in a collection at Borgo Sansepolcro. The Crucifixion is described there in considerable detail, together with three other subjects: a Flagellation, a Deposition, and a Resurrection, all three now lost. The writer did not claim that these panels came from the S. Agostino altarpiece, although in the same collection were four larger panels of standing saints that he specified did come from the high altar of S. Agostino. While he names only St. Michael and St. Augustine correctly, these larger panels may be identified with the four saints discussed in the entry on Piero’s St. John.

The seventeenth-century record does not, therefore, resolve the problem of whether or not The Crucifixion belonged to the same altarpiece. Piero did, after all, paint other works for his native town, which might have had predellas incorporating such scenes. The question of possible workshop participation in painting The Crucifixion is also an unresolved issue. Some scholars argue that an assistant was responsible for the execution, although certain passages of this small yet monumental composition are painted with great refinement. [3] |

|

|

Piero della Francesca, Crucifixion, Tempera and oil on panel, 37.47 x 41.12 cm Washington, Frick Collection

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca (c. 1415 - 1492)

Piero della Francesca (c. 1415 - 1492)

Augustinian Nun, 15th century

tempera on poplar panel

15 1/4 in. x 11 in. (38.74 cm x 27.94 cm)

Purchased by The Frick Collection, 1950. |

Piero della Francesca (c. 1415 - 1492)

Augustinian Monk, 1454-1469

tempera on poplar panel

15 3/4 in. x 11 1/8 in. (40.01 cm x 28.26 cm)

Purchased by The Frick Collection

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The façade and the bell tower of

San Marco in Florence |

|

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata

in Florence |

|

Florence, Duomo |

| |

|

|

|

|

Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists | Piero della Francesca

|

|

|

[1] Discussion on the subject of the central panel was closed when Polcri (1990) discovered a nineteenth-century description (1825) that states it was a Madonna and Child. The same researcher kindly informed me of the brief statement in a report of the Apostolic Visit of 16 August 1635 mentioning the Virgin, St Augustine and St Nicholas. At the time the polyptych was kept under the organ in Santa Chiara.

Other small dispersed panels have been connected with the group ofsaints in the central register. Two, one a St Monica and the other an Augustinian Saint, both from the Liechtenstein collection in Vienna, now in the Frick, have been connected on stylistic grounds, because of format (cm 39 by 28), and because the saints belong to the Augustinian family. These were added to by a third, depicting St Apollonia (41 by 28 cm), once in the Lehman Collection in New York and now at the National Gallery in Washington. Finally Longhi added a fragmentary Crucifixion, now in the University Museum at Princeton , to the series, supposing it to be the central panel of the predella. Later however, Longhi himself excluded that the St Apollonia was part of the polyptych, given that it is lit from the opposite direction to the other figures. The subject is debated by Meiss (1941), who follows the entire critical path th at has led to the recognition of the various parts of the polyptych, again by Longhi (1946), by Levi d' Ancona (1955) and finally by Davies (1961). The temptation to reconstruct the polyptych remains strong. Battisti (1971), Salmi (1979), and Paolucci (1989) propose reconstructions the most complex of which is Salmi's. In order not to sacrifice the St Apollonia, he imagines that the polyptych had two levels, with the Crucifixion (returned to its original size) at the centre of the upper one, with four compartments at its sides, while only the St Apollonia would remain of the eleven compartments (interrupted by a ciborium) in the lower register. He excludes the possibility that the small panels with saints were placed on pilasters, where instead Paolucci locates them. Recent cleaning of the Crucifixion has enhanced its gold background, but there is no certain evidence to connect the Princeton Crucifixion to the polyptych.

[2] Source: Art in The Frick Collection: Paintings, Sculpture, Decorative Arts, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996.| www.collections.frick.org

[3] Source: Art in The Frick Collection: Paintings, Sculpture, Decorative Arts, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996.| www.collections.frick.org

[4] Fra Angelico, The Coronation of the Virgin (about 1430 - 1432)

St Nicholas of Bari is shown kneeling in the foreground of The Coronation of the Virgin with his episcopal mitre and crook. St Nicholas's cope shows several scenes from the Passion, including the Betrayal, Mocking, and Flagellation.

|

|

|

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia article Piero della Francesca published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Piero della Francesca.

|

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

| |

|

|

|

|

. |

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

|

View from Podere Santa Pia

on the coast and Corsica |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Santa Trinita Florence |

|

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata

in Florence |

|

Arezzo |

| |

|

|

|

|

Sansepolcro

|

|

|

Legend has it that Sansepolcro’s origins can be traced back to two pilgrim saints, Arcano and Egidio. While returning from the Holy Land, they stopped in this valley and, thanks to a divine sign, they decided to stay and build a small chapel there to host the Holy Relics they’d brought from Jerusalem.

HISTORY

Between 1300 and 1500, Sansepolcro experienced an age of maximum splendor. The town’s historical center bears witness to centuries of commerce, art and culture. The center is encircled by walls, featuring gunners by Bernardo Buontalenti; it is located near the prestigious Fortezza di Giuliano da San Gallo. Visitors to the town are sure to appreciate its Medieval palaces, Renaissance towers and frescoed churches. The center is still true to its authentic feel which inspired the likes of Piero della Francesca. The artist used to sign his name ‘Pietro dal Borgo’ and he rendered his hometown immortal in many of his works, representing it as the ‘ideal city’ that was often debated in Italian courts.

Myriad artists are native of Sansepolcro including Raffaellino dal Colle, Cristoforo Ghepardi (called ‘Botine’) as well as architects Remigio andMarcantonio Cantagallina. In addition, it was the birthplace of many painters from the Alberti family as well as Santi di Tito.

HIGHLIGHTS

The town’s Civic Museum has numerous invaluable works such as ‘The Resurrection’ and the ‘Triptych of Mercy’ by Piero della Francesca. Visitors won’t want to miss its Aboca Museum and the Museum of Ancient Stained Glass. Its cathedral and the churches Santa Marta, Santa Maria delle Grazie, San Francesco, San Rocco and Sant’Antonio Abate are also certainly worth a visit. Together with the Medici Fortress and the House of Piero della Francesca, all of these cultural treasures make Sansepolcro an incredible Mecca for history lovers.

THE PALIO

Sansepolcro is famous for its ‘Palio della Balestra’ and its Flag-games. Visitors come from far and wide the second Sunday in September to see the festivities and traditional competition. Age-old rivals meet up to the sound of drums in Piazza Torre di Perta. The Palio della Balestra dates back to the 1400s when this free Commune had to continuously defend itself from neighboring lords.

In addition to the Palio, celebrated in honor of Saint Egidio, visitors will also appreciate the biennale of goldsmith art and the lace biennale, which spotlight two ancient forms of local craftsmanship.

(Fonte: Strada dei sapori della Valtiberina - Province of Arezzo)

|

|

Sansepolcro, Duomo

|

| |

|

Podere Santa Pia, morning view on the Maremma hills from the northern terrace |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

![]()