| |

|

Polyptych of the Misericordia (1445-1462)

|

|

|

| |

The Madonna della Misericordia or Virgin of Mercy is a traditional motif in Christian art which displays the Virgin Mary with an outstretched mantle. In the image, she uses her mantle to protect her worshippers. Artwork commissions with this theme were often made by groups [e.g., families, convents, guilds] who then were incorporated into the piece. Usually, the group is represented kneeling and of a smaller scale than the Madonna. Martin Luther scorned the image, likening it to "a hen with her chicks".

The oldest extant version is a small 13th Century piece by Duccio. The most famous example is The Madonna della Misericordia or The Polyptych of Misericordia, an altarpiece by Piero della Francesca in the Pinacoteca Comunale of Sansepolcro. Here Francesca features the Madonna as the centerpiece of the polyptych, flanked by the Virgin of the Annunciation, various saints, and images of the life of Christ. The piece was commissioned in 1445 by the Compagnia della Misericordia and was completed in 1462.

The Confraternita della Misericordia who commissioned the Madonna della Misericordia wanted a traditional altarpiece with gold leaf in the background. Despite this, Piero della Francesca demonstrates his mastery of perspective showing the Madonna’s cloak surrounding and sheltering the patrons of the painting. The flat gold leaf seems to be very much in the background as the figures are painted in perfect perspective.

Museo Civico Sansepolcro – Entrance Fee & Opening Hours

www.museocivicosansepolcro.it

Full price tickets cost €6.00, the civic museum in Sansepolcro is open 9.30 – 13.00 and 14.30-18.00 16th September to 14th June and 9.30-13.30 and 14.30-19.00 15th June to 15th September.

|

|

|

| |

Polyptych of the Misericordia (1445-1462) - Oil and tempera on panel, base 330 cm, height 273 cm, Pinacoteca Comunale, Sansepolcro |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The Flagellation of Christ (c. 1460)

|

|

|

| |

The flagellation is a recurring motif in Christian art which depicts a scene from the passion of Christ. Traditionally, this setting features Jesus tied to a column while being flayed with a scourge or whip. In Francesca's portrayal of this event, however, the main focus is not on the flaying but on a grouping of three men who stand in the right foreground. Their identitites are not known though studies of the work have yielded several possibilities. Their relationship to the tragic event in the background is also not clear.

There is no documentation of who commissioned this artwork or the location of the commission. The creation date is only an approximation. The piece is small, a modest 23 x 32 inches, which supports the possibility that the painting was meant for private use. Earliest commentary on the piece suggests that the aim of the patron was to keep the true intention of the work enigmatic. Absent valid documentation, the patron, the identity of the foreground trio and the purpose of the painting remains a mystery.

The Flagellation of Christ, was described by the art historian Kenneth Clark as “the greatest small painting in the world’. You can visit this painting in Federigo di Montefeltro’s Ducal palace in Urbino, now home to the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche. Federigo di Montefeltro was a successful mercenary captain who used his wealth to create a Renaissance court in Urbino, his hometown.

Piero’s Flagellation is illuminated by two light sources, the outdoor scene on the right shows three mysterious figures in the foreground apparently oblivious to what is going on behind them; this is lit from the left. The scene on the left, the Flagellation, is illuminated from the right. I haven’t found any explanation for this double light source, but almost certainly, it is symbolic of something.

The Flagellation of Christ once again shows Piero della Francesca’s mastery of perspective. I was told that someone put the painting with it’s intricate floor patterns into a computer program that converted it into a 3D model, as you would expect from this mathematician / painter, the computer’s 3D representation was perfect.

There are many theories as to who the three men in the foreground are. Some art historians say they represent Federigo’s father and the two advisors who supposedly murdered him, others that they are planning a crusade to retake Constantinople and that the painting draws parallels with the suffering of Christ and the fall of the Byzantine Empire.

|

|

|

| |

The Flagellation of Christ (c. 1460) - Tempera on panel, 59 x 81.5 cm, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

St. Jerome in Penitence (c. 1450)

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

St. Jerome in Penitence (c. 1450) - Oil on panel, 51 x 38 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta Praying in Front of St. Sigismund (1451)

|

|

|

| |

Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta grew up in a cultivated family with links to the humanist court of Ferrara: there the House of Este gave him his first wife, Ginevra (1419-1440). Summoning the greatest artists of the period, he turned Rimini into a major Renaissance center: Alberti (1404-1472) designed the facade of the church of San Francesco in Rimini, where the Malatestas were buried and whose paganistic interior earned it the nickname Tempio Malatestiano ("the Malatesta temple"). It was in this church, in 1451, that Piero della Francesca painted a fresco showing Sigismondo in profile, kneeling before his patron saint. The similarities between the fresco and the Louvre portrait (below) suggest that the latter was painted before 1451 and used as a model for the mural. |

|

|

| |

Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta Praying in Front of St. Sigismund (1451) - Fresco, Tempio Malatestiano, Rimini |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

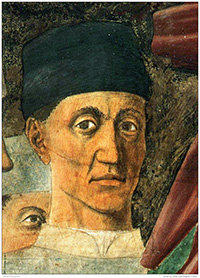

The Portrait of Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta portrays the condottiero and lord of Rimini and Fano Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, and is housed in the Musée du Louvre of Paris.

The portrait depicts the condottiero by profile and, according to some sources, was based on a medal executed in 1445 by Pisanello, or to one by Matteo de' Pasti from 1450. The picture itself was executed by Piero della Francesca during his sojourn in Rimini, during which he also painted the fresco with Sigismondo Pandolfo kneeling after St. Sigismund in the Tempio Malatestiano (Cathedral) of the city.

Despite the choice of the profile representation, typical of the portraits of eminent figures of the type, Piero della Francesca showed his attention for naturalist details in the fine execution of the texture and the hair of the committent. This is a proof of his good knowledge of Flemish masters such as Rogier van der Weyden.

Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta grew up in a cultivated family with links to the humanist court of Ferrara: there the House of Este gave him his first wife, Ginevra (1419-1440). Summoning the greatest artists of the period, he turned Rimini into a major Renaissance center: Alberti (1404-1472) designed the facade of the church of San Francesco in Rimini, where the Malatestas were buried and whose paganistic interior earned it the nickname Tempio Malatestiano ("the Malatesta temple"). It was in this church, in 1451, that Piero della Francesca painted a fresco showing Sigismondo in profile, kneeling before his patron saint. The similarities between the fresco and the Louvre portrait suggest that the latter was painted before 1451 and used as a model for the mural. |

|

|

| |

Portrait of Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta (c. 1451) - Tempera and oil on panel, 44.5 x 34.5 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

St. Jerome and a Donor (1451)

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

* St. Jerome and a Donor (1451) - Panel, 40 x 42 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

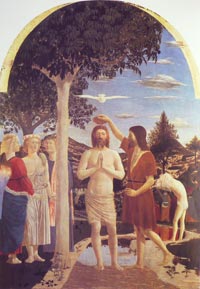

The Baptism of Christ (c. 1448-1450)

|

|

|

| |

Piero was born in Borgo Sansepolcro, in Tuscany. He worked in various central Italian towns, but retained links with Sansepolcro, visible in the background of the 'Baptism of Christ'.

This panel was the central section of a polyptych. It may be one of Piero's earliest extant works. Side panels and a predella were painted in the early 1460s, by Matteo di Giovanni (active 1452; died 1495). The altarpiece was in the chapel of Saint John the Baptist in the Camaldolese abbey (now cathedral) of Piero's native town, Borgo Sansepolcro. The town, visible in the distance to the left of Christ, may be meant for Borgo Sansepolcro: the landscape certainly evokes the local area.

The dove symbolises the Holy Spirit. It is foreshortened to form a shape like the clouds. God the Father, the third member of the Trinity, may originally have been represented in a roundel above this panel.

The baptism of Christ, originally part of a triptych, displays Francesca's utilization of the golden mean in the composition of the work. The figure of Christ, John's hand and the dove form a vertical axis which divides the painting in half. The tree on the left then creates a vertical axis which divides the left half by the golden mean.

During his teens [ca. 1439], Francesca studied his craft in Florence while working under Dominico Venezian on a series of murals for the hospital Santo Maria Nuova. It was also during this early part of his career that he began exploring the relationship between mathematics and art. One treatise authored by him, On perspective for painting, is the first to deal with the mathematics of perspective [creating a three dimensional effect in two dimensional works.

|

|

|

| |

The Baptism of Christ (c. 1448-1450) - Tempera on panel, 168 x 116 cm, National Gallery, London |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The History of the True Cross (c. 1455-1466)

|

|

|

| |

The History of the True Cross or The Legend of the True Cross is a sequence of frescoes painted by Piero della Francesca in the Basilica of San Francesco in Arezzo. It is his largest work, and generally considered one of his finest, and an early Renaissance masterpiece.

Its theme, derived from the popular 13th century book on the lives of saints by Jacopo da Varagine, the Golden Legend, is the triumph of the True Cross – the wood from the Garden of Eden that became the Cross on which Christ was crucified. This work demonstrates Piero’s advanced knowledge of perspective and colour, his geometric orderliness and skill in pictorial construction.

The main episodes depicted are:

* Death of Adam (390 x 747 cm). According to the legend, the tree from which the cross was made was planted, at the urging of angels, at the burial of Adam by his son, using a branch or a seed from the apple tree of the garden of Eden.

* The Queen of Sheba in Adoration of the Wood and The Meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (336 x 747 cm). According to the legend, the Queen of Sheba worshiped the beams made from the tree, and informed Solomon, that the Saviour would hang from that tree, and thus dismember the realm of the Jews. This caused Solomon to hew it down and bury it, until it was found by the Romans.

* Exaltation of the Cross (390 x 747 cm).

* Constantine's Dream (329 x 190 cm) Emperor Constantine the Great, before the battle of Milvian Bridge, is awakened by an angel who shows him the cross in heaven. With the cross on his shield, he slew the enemy, and later converted to Christianity.

* Discovery and Proof of the True Cross (356 x 747 cm). Helena, Constantine's mother, finds the cross in Jerusalem. It was not easy to get information and "when the queen had called them and demanded them the place where our Lord Jesus Christ had been crucified, they would never tell... her. Then commanded she to burn them all" or cast them into a dry pit for seven days and there torment them with hunger. He is shown in one fresco being pulled from the pit by a rope, whereupon he confessed that Jesus was his lord and where the cross was located. The proof of the cross was that it was used to resurrect a dead man.

* Battle between Heraclius and Khosrau (329 x 747 cm). The cross played a role in battles during the war between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Sassanid Empire (early 7th century).

Piero diverged from his source material in a few important respects, including the story of King Solomon's meeting with the Queen of Sheba in a chronologically inaccurate place and giving greater emphasis to the two battles in which Christianity triumphs over paganism.

The cycle ends with a depiction of the Annunciation, not strictly part of the Legend of the True Cross but probably included by Piero for its universal meaning.

Dating of the frescoes is uncertain, but they are believed to date from after 1447, when the Bacci family, commissioners of the frescoes, are recorded as having paid an unknown painter. It would have been finished around 1466. Most of the choir was painted in the early- to mid-1450s. Although the design of the frescoes is evidently Piero's, he seems to have delegated parts of the painting to assistants, as was usual. The hand of Giovanni da Piamonte, in particular, can be recognised in some of the frescoes.

|

|

|

| |

The History of the True Cross (c. 1455-1466) - Frescoes, San Francesco, Arezzo

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Saint Mary Magdalene (1460)

|

|

|

| |

More or less at the same time as he was working on the final scenes of the San Francesco cycle, Piero della Francesca was given another important commission in Arezzo: the fresco of Mary Magdalen in the Cathedral, situqated near to the door of the sacresty.

The construction of the Cathedral of Arezzo (San Pietro Maggiore) began around 1278, but spanned various epochs, indeed lasting until the early 16th century. The facade which had remained unfinished in the 15th century, was rebuilt in the 20th century in the neo-Gothic style on a design by Dante Viviani. Three stone measures of reference dating to the 13th century are walled on the south wall. The interior is a fine example of Gothic architecture, and abounds in works of art of great value.

This monumental figure of Mary Magdalen is created entirely by large patches of bright colours, rather like an early 16th-century Venetian painting. Yet even with this new use of colour Piero still concentrates on the attention to detail typical of his mature works: the shining light reflections on the small bottle, the hair that is depicted strand by strand on the saint's solid shoulders.

The saint is represented beyond an arch, which rises from a base just under two meters from the ground. Behind her, a marble parapet separates her from the sky, painted in azurite. |

|

|

| |

Mary Magdalene, fresco, 190 x 105 cm Arezzo, Duomo, 1460 |

|

|

Madonna del parto (1459-1467)

|

|

|

| |

The Madonna del Parto is a fresco painting Piero della Francesca finished around 1460. It is housed in the Museo della Madonna del Parto of Monterchi, Tuscany, Italy.

Piero della Francesca finished it in seven days of work, using first-rate colors, including a large extent of blu oltremare obtained by lapis lazuli imported from Afghanistan by the Republic of Venice

The portrayal of a pregnant Madonna was a theme depicted sometimes in the early 14th century Tuscany (examples include Taddeo Gaddi, Bernardo Daddi and Nardo di Cione). The Madonna was portrayed standing, alone, with a closed book on her belly, an allusion to the embodied Word.

Piero della Francesca's Madonna has neither books nor royal attributes as in the medieval predecessors of the picture. She is portrayed with a hand against her side to support her prominent belly. At her side are two angels, who are keeping open a pavilion decorated with pomegranates, a symbol of Christ's passion. The upper part of the painting is lost. The two angels are specular, as they were realized by the artist with the same holed fresco cartoons.

The theological symbolism behind the representation is rather complex. Maurizio Calvesi has suggested that the tent would be a representation of the Ark of the Covenant. Maria would be thus the new Ark of Alliance in her role as mother of Jesus. For other scholars the tent is a symbol of the Catholic Church and the Madonna would symbolize the tabernacle, as she is portrayed containing Jesus' body.

The fresco also plays an important role in Richard Hayer's novel Visus, in Andrei Tarkovsky's film Nostalghia, and in the poem "San Sepolcro" by Jorie Graham.

|

|

|

| |

Madonna del parto (1459-1467) - Detached fresco, 260 x 203 cm, Chapel of the cemetery, Monterchi |

|

|

| |

|

|

St. Julian (1454-58)

|

|

|

| |

This is the only fragment that has survived of Piero's fresco decoration of the church of Sant'Agostino in Borgo San Sepolcro. |

|

|

| |

St. Julian, Fresco, 130 x 105 cm Pinacoteca Comunale, Sansepolcro, 1454-58 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

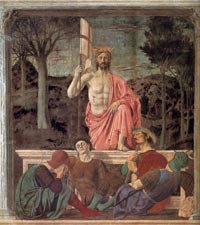

Resurrection of Christ (c. 1458)

|

|

|

| |

There are two great works of art by Piero della Francesca in the Museo Civico in Sansepolcro, the Madonna della Misericordia (Madonna of Mercy) and the Resurrection of Christ.

The resurrection is one of Piero della Francesca's mature works and features the artist as one of the sleeping soldiers at the feet of Christ. The painting is set at dawn, at the very moment of resurrection. The theme of new life is mirrored in the trees in the background, with the trees on the left still leafless and dormant and the trees on the right flush with growth.

During World War II Sansepolcro, believed to be a stronghold of German soldiers, came under artillery fire by the British. However, Antony Clarke, the captain in charge of the attack, remembered an essay by Aldous Huxley which described The resurrection as "the greatest painting in the world" [see The history of the true cross]. He ordered the bombardment to stop, sparing the town and the masterwork. The Allies later learned that there had been no enemy troops at the site after all.

The Resurrection of Christ is still on the wall where it was painted. Described by Aldous Huxley as the “greatest painting in the world” it is probably the first picture to deliberately use two vanishing points, a trick the cubists took to further extremes several centuries later. Christ emerging from the tomb is painted as if you are looking straight at him whereas the sleeping soldiers are painted as if you are looking up at them; the effect is to make Christ jump out from the painting. The Resurrection is heavy with the symbolism of renewal, the trees on the left have no leaves but the trees on the right are covered in foliage and the clouds are lit with a slight pinkish hue by the rising sun. It is said that the sleeping soldier in the brown tunic is a self portrait of Piero della Francesca.

Museo Civico Sansepolcro – Entrance Fee & Opening Hours

www.museocivicosansepolcro.it

Full price tickets cost €6.00, the civic museum in Sansepolcro is open 9.30 – 13.00 and 14.30-18.00 16th September to 14th June and 9.30-13.30 and 14.30-19.00 15th June to 15th September.

|

|

|

| |

Resurrection (c. 1458) - Fresco, 225 x 200 cm, Museo Civico, Sansepolcro |

|

|

Saint Mary Magdalen (1460)

|

|

|

| |

More or less at the same time as he was working on the final scenes of the San Francesco cycle, Piero della Francescawas given another important commission in Arezzo: the fresco of Mary Magdalen in the Cathedral. This monumental figure is created entirely by large patches of bright colours, rather like an early 16th-century Venetian painting. Yet even with this new use of colour Piero still concentrates on the attention to detail typical of his mature works: the shining light reflections on the small bottle, the hair that is depicted strand by strand on the saint's solid shoulders.

The fresco is located in the Cathedral near to the door of the sacresty.

|

|

|

| |

Saint Mary Magdalen, 1460, Fresco, 190 x 105 cm, Duomo, Arezzo |

|

|

Polyptych of Saint Augustine (1460-1470)

|

|

|

| |

In 1454 Piero agreed to paint a polyptych for the Augustinians of Borgo San Sepolcro. The painting was to be finished within eight years and was intended for their monastery. As usual, the work was not completed until much later. The polyptych later was replaced and dimembered. It was only in this century that scholars succeeded in reconstructing this work. Among the parts of the polyptych that have unfortunately not survived there is also the central panel. The panels that originally formed the predella are in the Frick Collection in New York. The figures of four saints are the outer decorations.

Archangel Michael is portrayed as an ancient warrior, his athletic limbs made more elegant by his precious armour, by the graceful tunic and by his beautiful boots decorated by with tiny pearls. There is nothing violent nor dramatic in the killing of the dragon, who is shown as a snake, its decapitated body lying on the ground. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Polyptych of Saint Augustine (1460-1470) - Oil and tempera on panel |

|

|

Madonna and Child Attended by Angels (1460-65)

|

|

|

| |

Madonna and Child with Four Angels (ca. 1470s-1480s), a relatively late work by Piero della Francesca. In this oil and tempera on wood panel, the artist reveals his antiquarian interests in classical Roman architecture encouraged at the court of Urbino.

Piero executed this painting for the Gherardi family. Members of this family were rich merchants in Sansepolcro in the fifteenth century.The Virgin's throne is placed under the open sky in a courtyard. This spatial arrangement was also used by Fra Angelico and his followers. The represented building with its decorative ornament has unusual iconographical and formal aspects if we compare it with buildings existing in the period.

The composition centers on the statuesque Virgin Mary, who holds a robust Christ Child on her knee. Christ reaches for a pink carnation, a symbol of the crucifixion. The stately angels, solid as columns, stand as sentinels, while the precisely calibrated architecture forms the idealized setting.

The Madonna, seated on a stool placed on a marble dais decorated with rosettes, offers a rose to the Child, who is seated on his mother's left knee and reaches out his hands to take the flower. Four standing angels surround the group, which is situated in a court yard illuminated by a tenuous light; an oblique shadow is projected from the first angel on the left towards the step of the throne. This is the only cast shadow in the entire painting.

|

|

|

| |

Piero della Francesca, Virgin and Child Enthroned with Four Angels, c. 1460-70, Williamstown, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute |

|

|

Nativity (c. 1470)

|

|

|

| |

Piero della Francesca was born in Borgo Sansepolcro, in Tuscany. He worked in various central Italian towns, but retained links with Sansepolcro, visible in a number of his works, such as the 'Baptism of Christ'. The distinctive rolling hills are also depicted in The Nativity.

Piero della Francesca was aware of Flemish painting, as can be seen in his Nativity. He probably knew the art of Rogier van der Weyden and may have met him, for Rogier was in Ferrara the same time (ca. 1450) as Piero. He would certainly have known Justus of Ghent, who served the court at Urbino. The Flemish qualities in Piero's work include his use of the oil paint technique and some iconographic types, such as the Madonna del Parto and the Madonna of Humility in the Nativity.

The missing patches of colour, which might almost indicate that the painting is unfinished, are in fact probably the result of overcleaning. |

|

|

| |

Nativity, c. 1470, Panel, 124,5 x 123 cm, National Gallery, London |

|

|

Polyptych of Perugia or Polyptych of St Anthony (c. 1470)

|

|

|

| |

Among the many works that, according to Vasari, Piero painted in Perugia, the historian describes with great admiration the polyptych commissioned by the nuns of the convent of Sant'Antonio da Padova. This complex painting, today in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Perugia, was begun shortly after Piero's return from Rome, but was not completed for several years.

The central part of the composition, the Madonna and Child with Staints Anthony, John the Baptist, Francis and Elisabeth, reveals in its unusual damask-like background the artist's aquaintance with a trend of contemporary Spanish painting, which Piero would have had the opportunity to see in Rome. We can therefore date the panel at around 1460. The polyptych is also made up of three predella panels showing St Anthony of Padua resurrecting a child, the Stigmatization of St Francis and St Elisabeth saving a boy who had fallen down a well, as well as two roundels placed between the main panel and the predella. The quality of this predella is extraordinary: Piero's characteristic spatial and light values are achieved here, on a small scale, by emphasizing the white walls of the interiors, the splashes of light and the deep shadows of the night scene in the open countryside. These scenes, where the bodies and even the shadows are fully three-dimensional, were to set an example for predella panels which was widely followed by Italian artists of the second half of the 15th-century, from the young Perugino to Bartolomeo della Gatta and, via Antonello da Messina, to the Neapolitan 'Master of Saints Severino and Sossio'. A few years later, Piero della Francesca completed the Perugia polyptych: above the ornate and still basically Gothic frame, he painted his extraordinary Annunciation.

The lack of compositional unity with the central part of the polyptych has led some scholars to suggest that Piero simply added this Annunciation to the altarpiece, much later. According to others, the whole polyptych has a structural unity; Piero simply cut out the top part, originally intended to be rectangular, and transformed it into a sort of cusped crowning. Once again Piero has succeeded in overcoming the limitations imposed by patrons with old-fashioned artistic taste, giving us one of the most perfect examples of his use of perspective. Thanks also to his use of oil paints, Piero della Francesca achieves the extraordinarily detailed depiction of the series of capitals, running towards the vanishing point. Each architrave, and each column as well, projects a thin strip of shadow into the splendid cloister arcade, which appears to go beyond any inspiration derived from Alberti's architecture. The subtle analysis of the decorations painted on the walls reaches an unprecedented level; yet everything is contained in a single and organic space. Distances, so perfectly calculated, are neither forced nor artificial: they are conveyed by the realistic light and atmosphere. |

|

|

| |

Polyptych of St Anthony, 1460-70, Panel, 338 x 230 cm, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria, Perugia |

|

|

Madonna and Child with Saints or the Brera Madonna ( 1472-1474)

|

|

|

| |

The Brera Madonna (also known as Pala di Brera, Montefeltro Altarpiece or Brera Altarpiece) is housed in the Pinacoteca di Brera of Milan, and was executed between 1472 to 1474.

Shortly after the Madonna of Senigallia, Piero set to work on the most grandiose of his paintings dating from this period. This was the huge altarpiece showing the Madonna and Child with Saints, today in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. Probably painted for the church of the Osservanti di San Donato in Urbino, this panel was transferred, after the death of Federico in 1482, to the church of San Bernardino, the modern mausoleum built for the deceased Duke. Federico da Montefeltro, shown kneeling at the foot of the Madonna's throne, is portrayed in his warrior's armour, but without the insignia awarded to him by Pope Sixtus IV in 1475.

The work represents a sacra conversazione, with the Virgin enthroned and the sleeping Child in the middle, surrounded by a host of angels and saints. On the right low corner, kneeling and wearing his armor, the Duke, patron of arts and condottiero Federico da Montefeltro. The background consists of the apse of a church in Renaissance classical style.

The characters' clothes, the angels' jewells, Federico's armor and the oriental carpet beneath the feet of the Virgin are depicted in great detail, reflecting the influence of Early Flemish painting.

|

|

|

| |

Madonna and Child with Saints (Montefeltro Altarpiece, 1472-1474) - Oil on panel, 248 x 170 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

|

|

|

Paired portraits of Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza (c. 1472)

|

|

|

| |

The Montefeltro family in Urbino was Piero's most generous patron towards 1465. The diptich with the portraits of Battista Sforza and Federico da Montefeltro can be dated at the beginning of this period. In these two relatively small panels Piero attempts a very difficult compositional construction, that had never been attempted before. Behind the profile portrait of the two rulers, which is iconographically related to the heraldic tradition of medallion portraits, the artist adds an extraordinary landscape that extends so far that its boundaries are lost in the misty distance. Yet the relationship between the landscape and the portraits in the foreground is very close, also in meaning: for the portraits, with the imposing hieratic profiles, dominate the painting just as the power of the rulers portrayed dominates over the expanse of their territories. The daringness of the composition lies in this sudden switch between such distant perspective planes.

Piero's ability in rendering volumes is accompanied by his attention to detail. Through his use of light, he gives us a miniaturistic description of Sforza's jewels, of the wrinkles, moles and blemishes on Federico's olive-coloured skin.

On the right: Portrait of Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Madonna di Senigallia (c. 1474)

|

|

|

| |

The Madonna di Senigallia was finished Piero della Francesca around 1474. It is housed in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, in the Ducal Palace of Urbino.

The painting was originally in the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie outside the walls of Senigallia, whence the current name.

The painting is quite different from Piero's previous production. The faces still have an expression of aloofness and of superior rational wisdom, but they also convey a sense of precious, almost exotic, beauty. This is one of the paintings in which the artist most clearly reveals his interst in light values, both in terms of reflections and of magical transparencies.

The 1950s restoration showed the high quality of Piero della Francesca's treatment of light, as well as the influence of Flemish masters on it in details such as the basket with linen gauze, the coral and the fabric covering the Madonna's head. The light, which realistically enters from the window on the left, is a symbol of the Virgin's conception. The linen in the basket is instead an allusion to her purity, while the case for hosts in the shelf and the coral hanging from Jesus' necklace both hint to the Eucharist sacrifice. The staring, thoughtful immobility of all the characters would be also an allusion to the latter. |

|

|

| |

Madonna di Senigallia (c. 1474) - Oil on panel, 67 x 53.5 cm, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

![]()