| |

|

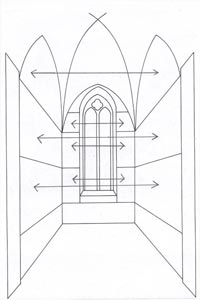

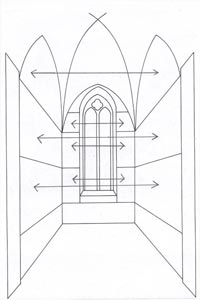

One of the most demanding aspects of the cycle is the way Piero arranged the scenes on the walls. Although the story of the Cross is of longue duré - a compilation of medieval legends beginning in the time of Genesis and progressing to the 7th century A.D. - it follows a simple chronological sequence. One might expect such a narrative told visually to "read" like pages in a book; that is, to start on the left at the top; move from left to right, and proceed down the walls, tier after tier. Piero chose not to tell the story in this manner, but to rearrange the sequence in a dramatic way. He placed his Genesis scenes not on the left, but on the right wall at the top and made them read "backwards" from right to left. He put the next episodes on the second tier and reversed the order to read left to right. He then had the story jump to the second tier of the right side of the altar wall and progress diagonally down to the lowest tier on the left side, and so on. Figure 2 shows how the "Narrative Sequence" continues in this "irregular fashion," ending, not at the bottom but at the top tier of the left wall!

The legacy of Piero's "rearranged" chronology has two parts:

1. Jumping around the space reminds one of the chaotic rhythms of a medieval romance, the Roman de la Rose, for example. Such stories, which apparently St. Francis loved when he was a boy, are full of adventure, with stalwart knights and ladies fair, and always a moral overtone and religious goal. Their structures are full of surprising stops and starts, changes of direction, and what the modern mind considers to be irrational time changes. The Legend of the True Cross, as it developed, came out of this very tradition, and Piero did not want his viewers to forget this fact.

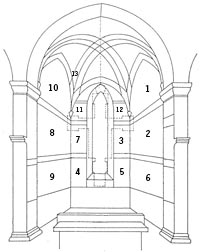

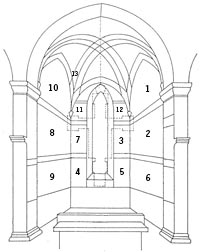

2. At the same time, Piero’s arrangement makes the story take on another character, one that is abstract in nature and serious in implication. The two lunettes at the top of the side walls match, showing the beginning and the end of the story, each centered in the wood of the cross. The second tiers match; they express the power of royal women who are divinely inspired to recognize the holy wood. On the altar wall, scenes on either side of the window match: the top tiers show Old Testament prophets who foresaw the coming of Christianity and the story of the cross; the second tiers represent a form of comic relief with serious undertones. They are genre scenes of every day that allude to Christ’s passion and the Eucharist. The bottom tiers also match. Both are scenes of annunciation: one of the birth of Christ, the other the birth of Christianity. The bottom tiers on the side walls match. They are scenes of battle: one is a bloodless victory over fellow Romans at the sign of the cross, and the other is a bloody battle for victory over the blasphemous infidels. Figure 3 shows this "Thematic Balance." The effect of this new arrangement creates the symmetry and balance, the gravity and dignity required by Aristotle and Horace for creating epic poetry. By dint of his re-organized disposition, Piero achieved what might be called the first modern epic.

The main episodes depicted are:

|

|

Piero della Francesca painted a self portrait in The Discovery and Proof of the True Cross Piero della Francesca painted a self portrait in The Discovery and Proof of the True Cross

Thematic balance

Narrative sequence

|

|

1 Death of Adam; Seth meeting the Archangel Michael

2 The Adoration of the Holy Wood; the Queen of Sheba kneels in front of the wood from which the cross will be made and meets King Solomon

3 The burial of the Sacred Wood

4 The Annunciation to Mary

5 The Vision of Constantine

6 The Victory of Constantine (Constantine's victory over Maxentius at the battle of Milvian Bridge)

7 The Torture of Judas the Jew

8 The Discovery and Proof of the True Cross

9 The Battle of Heraclius and Chosroes

10 The Exaltation of the Cross

11 The Prophet Jeremiah

12 The Prophet Isaiah

13 An angel

|

|

Piero’s figurative distribution was affected by the chapel’s configuration, which Piero divided into three sections: the upper lunettes and two lower rectangular sections.

The symmetry of the side walls is perfect: in the upper part, two episodes set in the open air are one opposite the other (1) Adam’s Death and The Exaltation of the Cross (10), in the median section there are two scenes of court life, The Queen of Sheba kneeling in adoration of the wood on the stream Siloe and meeting Salomon (2) and The discovery and proof of the True Cross (8), and in the lower section two battles, The Victory of Costantin over Maxentius (6) and The Battle of Heraclius and Chosroes (9). The central wall completes the narration with The Vision of Constantine (5), The Annunciation to Mary (4), The Prophet Jeremiah (11) and The Prophet Isaiah (12); as for the scenes The burial of the Sacred Wood (3) and The Torture of Judas the Jew (7), the drawings were certainly made by Piero, though were painted by Giovanni Piamonte. |

| All of these frescoes, including The Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes, contain many of the stylistic and scientific developments of painting that occurred during the Early Renaissance: a love for monumental compositions, the use of perspective, proportions, light, and colour to create realism in both figures and landscape. Typical of the Early Renaissance, the expressions of the figures are calm and detached even as they engage in battle |

| |

|

|

|

Death of Adam

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, Death of Adam, Seth meeting the Archangel Michael, c. 1466, fresco (390 x 747 cm), San Francesco, Arezzo

|

On the right, the ancient Adam, seated on the ground and surrounded by his children, sends Seth to Archangel Michael. In the background we see the meeting between Seth and Michael, while on the left, in the shadow of a huge tree, Adam's body is buried in the presence of his family. By placing all three stages of the story within the same background landscape, Piero is abiding by traditional narrative schemes already used by Masaccio in his fresco of the Tribute Money in the Brancacci Chapel.

The Legend recounts how, on the point of death Adam begs his son Seth to go to the archangel Michele to procure the oil of mercy. The archangel refuses and instead gives Seth the seeds of the tree of sin, ordering him to plant them in the mouth of his dying father in order to save his soul. Seth obeys and once buried, the tree of Good and Evil springs up from the mouth of Adam, thus saving him. This tree is forgotten about over the years until the moment in which King Solomon orders the building of the Great Temple of Jerusalem when in fact, the tree is used in erecting a bridge over the waters of the River Siloah. The Queen of Sheba visits Solomon, and while crossing the bridge she suddenly has the vision that this plank over the river will be used in building the Cross of Jesus. On hearing this King Solomon orders the burial of the plank in order to prevent the vision from coming true.

|

|

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, Death of Adam, c. 1466, fresco 390 x 747 cm, (detail) San Francesco, Arezzo |

| |

Adoration of the Holy Wood and the Meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, Adoration of the Holy Wood and the Meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba

|

Piero diverged from his source material in a few important respects, including the story of King Solomon's meeting with the Queen of Sheba in a chronologically inaccurate place and giving greater emphasis to the two battles in which Christianity triumphs over paganism.

According to the legend, the Queen of Sheba worshiped the beams made from the tree, and informed Solomon, that the Saviour would hang from that tree, and thus dismember the realm of the Jews. This caused Solomon to hew it down and bury it, until it was found by the Romans.

The tree that grew on Adam's grave was chopped down in King Solomon's times, but its wood could not be used for anything, so it was thrown as a bridge across a stream. The Queen of Sheba on her way to the King Solomon was about to step on the bridge, when by miracle she knew that the Savior would be crucified on a Cross of that wood. Instead of stepping on the wood she knelt and expressed her adoration. (The Queen of Sheba in Adoration of the Wood. Left part of the fresco 8). Then she hurried to Solomon to tell him about her revelation (The Meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Right part of the fresco 8). After Solomon learnt about the divine message he understood that the wood would cause the end of the kingdom of the Jews, and ordered the bridge be removed and the wood be buried. (Burial of the Wood, fresco 7).

Centuries later Mary received the angel's message that she was chosen to give the birth to the Savior (Annunciation. Fresco 10) Solomon's precautions did not help - the wood was found and Jesus was crucified on a Cross made of it.

Adoration of the Holy Wood (left view) Behind the Queen of Sheba, kneeling in adoration, is her retinue of aristocratic ladies in waiting, with their high foreheads (according to the fashion of the time) emphasizing the round shape of their heads and the cylindrical form of the neck. Their velvet cloaks softly envelop their bodies, reaching all the way to the ground. The almost perfect regularity of the composition is underlined by the two trees in the background, whose leaves hover like umbrellas above the two groups of the women and of the grooms holding the horses. And yet Piero's constant attention to the regularity of proportions and the construction according to perspective never gives way to artificially sophisticated compositions, schematic symmetries or anything forced.

Meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (right view) This famous scene takes place within an architectural structure, enlivened by decorations of coloured marble. Everything seems created according to architectural principles: even the three ladies standing behind the Queen are placed so as to form a sort of open church apse behind her. There is a real sense of spatial depth between the characters witnessing the event; and their heads, one behind the other, are placed on different planes. This distinction of spatial spaces is emphasized also by the different colour tonalities, with which Piero has by this stage in his carrer entirely replaced his technique of outlining the shapes used in previous frescoes.

There is an overall feeling of solemn rituality, rather like a lay ceremony: from Solomon's priestly gravity to the ladies aristocratic dignity. Each figure, thanks to the slightly lowered viewpoint, becomes more imposing and graceful; Piero even succeeds in making the characteristic figure of the fat courtier on the left, dressed in red, looks dignified.

|

|

The Meeting of Solomon and

the Queen of Sheba

|

| |

Burial of the Wood

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, Burial of the Wood, c. 1466, fresco 390 x 747 cm, (detail) San Francesco, Arezzo

|

| At the end wall of the chapel, around the stain-glass window and below the prophets were placed the Burial of the Wood (on the left) and the Torture of the Jew (on the right). These two stories were painted by Piero's main assistant Giovanni da Piamonte.

In the Burial of the Wood, Giovanni da Piemonte's heavy modelling draws the stiff folds of the bearer's garments and their hair, rather mechanically tied in bunches. On the Cross the vein of the wood, like an elegant decorative element, forms a halo above the head of the first beare, who thus appears as a prefiguration of Christ on the way to Calvary. The sky covers half the surface of the fresco and the irregular white clouds are as though inlaid in the expanse of blue.

Disposal of the recalcitrant piece of wood is crucial to the continuity of the Story of the True Cross, since it identifies the wood’s location during the time between the Old and New Testaments. It is significant that Piero disassociates the image of this destructive act from the noble king, placing it on the altar wall, as far away as possible while remaining on the same side of the apse and at the same level.

Three Workmen Bury the Wood

Three slovenly men struggle to push what is now a plank of wood into a body of water. The first has disheveled his clothes in the strain; the second, pushing up with a stick, bites his lip with exertion. The third uses only his hands to push, while the wreath on his head implies a bit of tippling. Following Solomon’s orders, they are trying to hide the wood forever, but to no avail. Much later the wood will rise to the surface of what became known as the Probatic pool, working miracles by healing the sick and the lame who came to bath there.

Piero has encapsulated these events by focusing on the workmen who know nothing of their mission. He creates what appears to be a genre scene, again with implied relationships across the corner. On the right, the back-side of the drunken workman is juxtaposed and thereby equated to the hindquarters of a horse on the adjacent wall. Another nearby horse “laughs” at this interaction. At the same time, the lead worker, who exposes his nether parts, is made to prophesy the future function of the wood by taking the pose of “Christ Carrying the Cross,” even having a kind of halo in the grain of the wood behind his head. The diagonal of the plank extends beyond the frame, leading down to the next scene in the sequence. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The Annunciation to Mary

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, The Annunciation to Mary, c. 1455, fresco, 329 x 193 cm, San Francesco, Arezzo

|

The cycle ends with a depiction of the Annunciation, not strictly part of the Legend of the True Cross but probably included by Piero for its universal meaning.

With the scene of the Annunciation, the chronology of the story enters the time of the New Testament. This scene is not ordinarily included in the True Cross legend. Never inappropriate in cycles concerned with the theology of salvation, the Annunciation may have been required here in remembrance of the important indulgence, granted in 1298 and often renewed, awarded to all visitors who worshipped in the church on March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation.

God-the-Father and the Angel

Piero has created an ingenious four-part composition that combines heaven and earth. God-the-Father carried on clouds in the upper left quadrant emits golden rays from his hands. [Very little of the gold, applied after the plaster is dry, remains on any of the frescoes.] At the same moment the Angel Gabriel alights below, in the forecourt of Mary’s house. He is silhouetted against the intricately carved doorway, which is closed, fulfilling the prophecy of Ezekiel (44:2; perhaps represented in the figure depicted two tiers above). Gabriel proffers not a lily but a palm frond, thus announcing not only the incarnation of Christ but also the future death and compassion of Mary herself. The palm is known as the key to paradise, lost when Eve sinned but returned when Mary died. The sin of Eva is unlocked by this key as Gabriel utters the greeting Ave, its reverse.

The Virgin Mary

Piero paints Mary as a massive figure, tall as a column (another of her epithets), of great nobility and acquiescence. Her scale and demeanor qualify her as a symbol of the Church, while her expression and grace are full of human warmth. Her house, the “Casa Santa,” is a marble-encrusted, classicizing dwelling. Through the open doorway, her thalamus or marriage-bed is visible, alluding to the Marriage of Christ and Ecclesia that is taking place at the Annunciation. In the upper right quadrant, the shadow of the tapestry bar passes through the hanging-loop, again symbolizing Mary’s unbroken virginity. More than any other scene, the Annunciation transforms medieval symbolism into a vista of the new rationally measured world of the Renaissance. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

The Vision of Constantine

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, Constantine's Dream, c. 1455, fresco, 329 x 190 cm, San Francesco, Arezzo

|

Constantine the Great (c. 280-337), was a Roman Emperor, the son of Helena. He came to overall power in 312 after defeating the Emperor Maxentius at the battle of the Milvian bridge on the Tiber, an event traditionally regarded as the turning point in the establishment of Christianity within the empire. According to Eusebius' Life of Constantine (1:27-32), on the eve of the battle Constantine saw in a dream a cross in the sky, and heard a voice saying, 'In hoc signo vinces' - 'By this sign shalt thou conquer.' Henceforth, it is said, he substituted the emblem for the Roman eagle on the standard, or laborum, of the legions.

This scene is set in the middle of the night. Inside his large tent, the Emperor lies asleep. Seated on a bench bathed in light, a servant watches over him and gazes dreamily out towards the onlooker, as though in silent conversation. With a daring innovation, that almost seems to anticipate Caravaggio's modern concept of light, the two sentries in the foreground stand out from the darkness, lit only from the sides by the light projected from the angel above.

Piero della Francesca | The History of the True Cross | The Vision of Constantine |

|

Agnolo Gaddi, Dream of Emperor Heraclius (detail),1385-87, fresco, Chancel Chapel, Santa Croce |

|

Battle between Constantine and Maxentius | Battle of the Milvian Bridge

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, Battle between Constantine and Maxentius, c. 1458, fresco, 322 x 764 cm, San Francesco, Arezzo

|

The Battle of the Milvian Bridge took place between the Roman Emperors Constantine I and Maxentius on 28 October 312. Constantine won the battle and started on the path that led him to end the Tetrarchy and become the sole ruler of the Roman Empire. Maxentius drowned in the Tiber during the battle.[4]

This episode certainly carried an important idealistic hidden meaning and also touched on contemporary events, at a time when Pius II was planning a crusade against the Turks. All attempts to reconcile the two churches had in fact failed, so that, after the Turkish conquest of Constantinople, the only solution appeared to be to unite all Christians in the struggle against the Infidel.

In Piero della Francesca's fresco, Constantine face is a portrait of John VIII Palaeologus, former Eastern Emperor. And just as Constantine had gone into battle, leading his troops carrying the symbol of the Cross, so the modern Emperor can defeat the Infidel by leading all Christian armies into battle. But beyond this symbolism the battle between Constantine and Maxentius is depicted as a splendid parade, from which the crashing of arms has definitely been eliminated. The absence of movement immortalizes the horses with raised hoofs in the act of jumping, the shouting warriors with open mouths, all fixed once again by the unbending rules of construction according to linear perspective. Compared to the Battle of San Romano, painted by Paolo Uccello about twenty years earlier and which was one of the highest achievements of that Florentine pictorial perspective that inspired the young Piero, in the Arezzo fresco there is a totally new depth of space between the figures. A realistic atmosphere, conveyed by the bright lighting, emphasizes the various spatial planes. Within this composition, Piero della Francesca succeeded in reproducing, thanks to his highly refined use of bright colours, all the visual aspects of reality, even the most fleeting and immaterial ones. From the reflections of light on the armour, to the shadows of the horses' hoofs on the ground, to the wide open sky with its spring clouds tossed by the wind, the reality of nature is reproduced exactly, down to its most ephemeral details.

The Victory of Constantine | According to the legend surrounding the battle, Constantine and Maxentius both being Romans, no blood could be shed between them. Maxentius had devised a ruse by which Constantine’s army would be drowned in the Tiber. Part of Constantine’s revelation was that with the power of the Cross his victory was assured, and so, entering the fray with only the angelic gift, he won.

Constantine and his Army | At the left margin of the tier there is represented a portion of the head of a horse. With this detail, Piero implies that there is more of the army yet to come out from behind the wall. Amid a forest of lances and thundering hoofs, the cavalry, surmounted by a glorious imperial eagle flag, calms as it moves left to right and stops at the figure of Constantine, erect on his white horse. He extends his arm to display the tiny [formerly gold] cross, the talisman of righteous power, faith, and victory. His profile head is aglow with masculine beauty. He wears a contemporary Byzantine pointed hat which, in Piero’s time, was believed to be in the style of the ancients. The imperial crown nestles there behind the brim, indicating that the battle is already won.

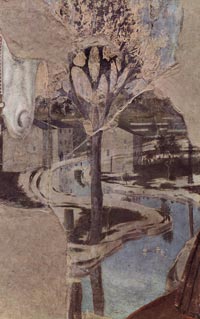

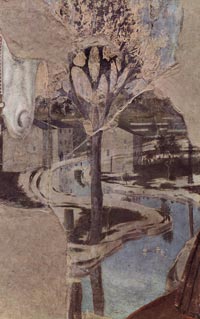

The Rout of Maxentius | The scene in the right half of the time has suffered great losses of paint over the centuries. It takes place before a Tuscan landscape near the source of the Tiber. With its country houses and calm reflections in the water (notice the ducks floating on the surface), the battle has thus been relocated to the outskirts of Arezzo. The forces of Maxentius are in flight. An equestrian officer scrambles up the river bank. All that can be seen of Maxentius himself is the peak of his headgear, indicating that it was in the same Greek-style hat as Constantine’s but with the colors reversed. As the loser, he is identified as ignoble by his routed, naked slave, and by the venomous basilisk blazon on his flag. |

|

Tiber

|

| |

|

|

|

The Torture of Judas the Jew

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, The Torture of Judas the Jew (detail), c. 1455, fresco, 356 x 193 cm, San Francesco, Arezzo

|

At the end wall of the chapel, around the stain-glass window and below the prophets were placed the Burial of the Wood (on the left) and the Torture of the Jew (on the right). These two stories were painted by Piero's main assistant Giovanni da Piamonte. He was an artist of considerable talent who managed to follow Piero's style remarkably well in the frescoes in Arezzo, executing the cartoons designed by the master. His heavier hand gives the figures a more peasant look, with pronounced features, fleshy lips, almost Negroid, as in the figure of Judas in the Torture of the Jew.

In the Torture of the Jew, despite the dramatic nature of the subject, which should give rise to a great sense of movement, we find the contrary. Piero's world is governed by measured perspective, eliminating all unplanned movement. If we forget for a oment the subject of the story, the scen could appear to be taken place in a peaceful princely court.

Following Constantine’s conversion, his mother, the Empress Helena, also became a devoted Christian and traveled to Jerusalem to search for the True Cross. There she learns that only one man, ironically named Judas, knows where the Cross is hidden, and when he refuses to give up the secret, Helena’s men throw him into a dry well. After seven days of torture, Judas relents and is taken to Helena where, reluctantly, he indicates the whereabouts of the Cross. Judas brought Helena to the temple of Venus under which the three crosses of Calvary were hidden. Helena ordered the temple be destroyed and under it the three crosses were discovered (The Discovery and Proof of the True Cross, left part of the fresco 8). A way had to be found to prove which of the three crosses was the one on which Jesus had been crucified. The crosses were placed in the centre of the town. A body of a young man was being carried past and Judas halted the cortege. When Judas held the third cross over the corpse, the young man came back to life. The true cross was thus identified. This became one of the most important scenes of Piero della Francesca, the ‘Finding and the Proof of the True Cross’.

Two rather fancily dress youths pulls down on the rope of a pulley, hoisting Judas to ground level. Another official forces him to take the last step by pulling his hair. The scene may strike one at first as rather bizarre, which it is, but it also has a deeper meaning. The Old Testament high priest Habakkuk was taken forcibly by the hair by an angel when he refused to deliver food to Daniel (in the lion’s den). Thus both men were taken where they did no wish to go and ended by performing deeds of a higher good. Judas soon understood and for his devotion, he was later named bishop of Jerusalem. This scene, like its partner on the opposite side of the window, is often attributed to one of Piero’s assistants, Giovanni di Piamonte, who followed the master’s style closely, but in a slightly cruder version called for by his subjects. The clouds that seem to be in front of the pulley supports were painted in fresco. After the plaster was dry, the stakes were painted over the clouds in tempera, some of which has flaked off.

Judas was later baptised and given the name Quiriacus. Still later he was ordained bishop of Jerusalem. |

|

|

| |

|

|

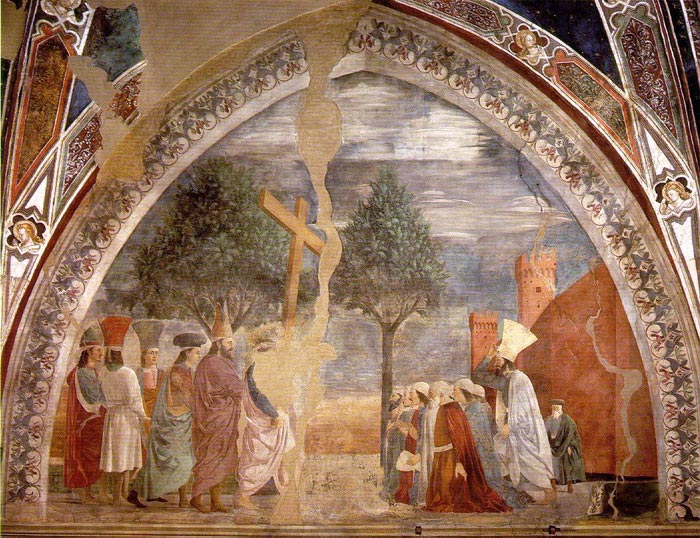

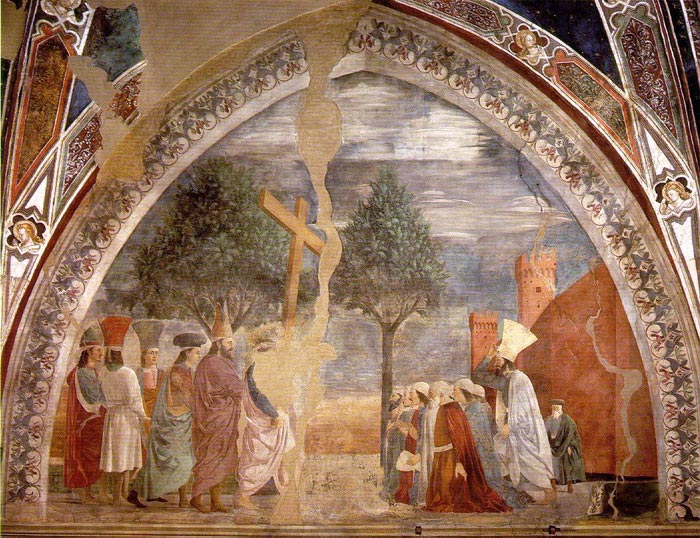

The Invention of the Cross | Discovery and Proof of the True Cross

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca,, Discovery and Proof of the True Cross, c. 1460, fresco, (356 x 747 cm), San Francesco, Arezzo

|

This is one of Piero's most complex and monumental compositions. The artist depicts on the left the discovery of the three crosses in a ploughed field, outside the walls of the city of Jerusalem, while on the right, taking place in a street in the city, is the Proof of the True Cross. His great genius which enables him to draw inspiration from the simple world of the countryside, from the sophisticated courtly atmosphere, as well as from the urban structure of cities like Florence or Arezzo, reaches in this fresco the height of its visual variety.

The Discovery and Proof of the True Cross is one of the largest frescoes in the church. Two scenes are depicted in the same one picture. To the left, Judas has indicated the place of the burial of the crosses. Judas stands next to the hole that was dug. He shows the Cross to Queen Helena who is accompanied by her court, which includes a dwarf. Men with shovels stand next to the pit and a man heaves the Cross from the ground, out of the earth, to Helena and Judas. Behind the rocks of the Mount of Olives rises Jerusalem, which is an idealised view of Arezzo.

|

| |

|

|

|

Piero della Francesca, Discovery and Proof of the True Cross, (detail), c. 1460, fresco, (356 x 747 cm), San Francesco, Arezzo

|

The scene on the left is portrayed as a scene of work in the fields, and his interpretation of man's labors as act of epic heroism is further emphasized by the figures' solemn gestures, immobilized in their ritual toil.

At the end of the hills, bathed in a soft afternoon light, Piero has depicted the city of Jerusalem. It is in fact one of the most unforgettable views of Arezzo, enclosed by its walls, and embellished by its varied colored buildings, from stone gray to brick red. This sense of color, which enabled Piero to convey the different textures of materials, with his use of different tonalities intended to distinguish between seasons and times of day, reaches its height in these frescoes in Arezzo, confirming the break away from contemporary Florentine painting.

In the scene on the right Helena has knelt in the middle of the town, below the temple to Minerva, whose facade in marble of various colors is so similar to buildings designed by Alberti, Empress Helena and her retinue stand around the stretcher where the dead youth lies; suddenly, touched by the Sacred Wood, he is resurrected. The sloping Cross, the foreshortened bust of the youth with his barely visible profile, the semi-circle created by the Helena's ladies-in-waiting, and even the shadows projecting on the ground - every single element is carefully studied in order to build a depth of space which, never before in the history of painting, had been rendered with such strict three-dimensionality. |

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, Discovery and Proof of the True Cross, (detail), c. 1460, fresco, (356 x 747 cm), San Francesco, Arezzo

|

Exaltation of the Cross

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, Exaltation of the Cross, c. 1466, fresco, (390 x 747 cm), San Francesco, Arezzo

|

Exaltation of the Cross is he last episode of the cycle. The figure of the the Emperor is almost entirely illegible now. The Oriental noblemen wear splendid Greek headdresses, the exotic elegance of them had been admired by all Florentines at the time. Piero's interest in these enormous hats, cylindrical or pyramidal in shape, is dictated by the same motives which had driven Paolo Uccello to concentrate on the complex armour of contemporary warriors - the study of shapes and perspective.

And the colours of the garments are more lively, too. In the midday light and under the blue sky, they vary from pale blue to violet, from bottle-green to pearl-white. This scene is the confirmation that Piero wishes to depict an ideal mankind, healthy and strong, with a peaceful expression, characterized by calm, measured gestures. He conveys the impression of a race of mature men, rationally at peace with themselves. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes, c. 1466, fresco, 329 x 747 cm, San Francesco, Arezzo

|

| |

|

|

|

The Eastern Emperor Heraclius wages war on the Persian King and, having defeated him, returns to Jerusalem with the Holy Wood. But a divine power prevents the emperor from making his triumphal entry into Jerusalem. So Heraclius, setting aside all pomp and magnificence, enters the city carrying the Cross in a gesture of humility, following Jesus Christ's example.

The True Cross became famous over the centuries as it performed miracle after miracle. According to the legend, the Sassanian king Chosroes II (590-628; Khosrau in Persian) coveting its power, stole the relic and used it to subjugate his citizens. Heraclius, Emperor of Byzantium, in A.D. 528 came with his troops to rescue the cross by force.

Piero della Francesca interpreted the encounter as a complex battle spreading across the wall from left to right, full of blood and heavy weaponry. Painted in exquisite detail, the procession to victory can be read in the flags, moving from the imperial eagle to the standards of Islam, one, decorated with Moorish figures, in tatters, the other with crescent moons, falling to the ground. The warriors on both sides wear all sorts of armor, including colorful Roman molded leather cuirasses and Renaissance style harnesses of polished laminated steel, reflecting the real light that streams from the window on the altar wall. A war-weary bugler in a tall white hat sounds his horn, while all around him weapons fly through the air. At the right-hand edge of the battle, a mounted knight receives a dagger-thrust to the throat, and as he falls back seems to regurgitate the cross from his very mouth. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| At the far right, the cross forms part of the blasphemous Trinitarian tabernacle the Chosroes had set up. He called himself God, mounting the cross on his right as the Son, and a cock on a column on his left as the Holy Spirit. Having refused baptism, Chosroes leaves his throne empty and kneels awaiting the executioner’s sword. Around him are his judges, in the guise of members of the Bacci family, the fifteenth-century patrons of the chapel. By showing Chosroes with the same features as God-the-Father (Who appears around the corner in the Annunciation scene), Piero defines visually his criminal blasphemy. [4] |

|

|

| |

| This detail shows the trumpeter on the left side of the fresco, who, in the midst of this dramatic battle, continues to play his instrument. On either side of this figure the imposing presence of the two warriors in their shining armour is remarkable.

|

|

Piero della Francesca, Battle of Heraclius and Cosroe, (detail of the trumpeter with the Byzantine hat) |

| |

|

|

|

Two Old Testament Prophets

|

| |

|

Piero della Francesca, The Old Testament Prophet Jeremiah (detrail), c. 1466, fresco, 329 x 747 cm, San Francesco, Arezzo

|

| |

|

|

|

Despite being youthful and beardless, the two figures on either side of the window in the top of tier of the altar wall are Old Testament prophets who forecast the coming of Christianity. Their identity, however, is not designated.

The Right Prophet (Jeremiah?), the young man on the right holds a banderole, which for some reason was left blank. Isaiah, who prophesied the Virgin Birth, has been suggested. Jeremiah is even more likely: Jeremiah foretold the coming of the messiah, quoting God as saying “I will raise up to David a just branch: and a king shall reign . . . and shall execute judgment and justice in the earth” (23:5). The interplay between this handsome figure and the blond youth across the corner -- one of the vistas the Model makes possible -- suggests that Adam’s young offspring, having learned that death is the result of sin, hears the prophetic words and perceives the future redemption through the cross.

Based on the similarity with the young barefoot appearing in the Flagellation of Piero, Silvia Ronchey recognizes Geremia in the likeness of Thomas Palaeologus, the younger brother of John VIII and last despot of Morea.

Thomas Palaiologos was the youngest surviving son of the Byzantine Emperor[1][2][3] Manuel II Palaiologos and his wife Helena Dragaš. Like other imperial sons, Thomas Palaiologos was made a Despot (despot?s), and from 1428 joined his brothers Theodore and Constantine in the Morea. After the retirement of Theodore during 1443, he governed together with Constantine, until the latter became emperor (as Constantine XI) during 1448..[5]

Left Prophet Ezekiel

The prophet Ezekiel proclaimed: “This gate shall be shut, it shall not be opened, and no man shall pass through it: because the Lord the God of Israel hath entered in by it, and it shall be shut” (44:2). His words were interpreted as a description of the arrival of the messiah and of the eternal virginity of Mary, who is given the epithet “Porta Clausa.” The figure’s location high above the scene of the Annunciation and the closed door in that composition helps to identify this exclamatory figure.

On the walls of the chancel arch are frescoes which depict an angel, Cupid, St. Louis, St. Peter, St. Augustine and St. Ambrose.

Piero painted a fascinating angel's head (the angel on the left), within a quatrefoil frame. This is the angel that would later look on the scene of the Death of Adam. The other missing angel he left to an assistant, identified as Giovanni di Piamonte.[6]

In addition, there is a fine painting of St Mary Magdalene, also by Piero della Francesca, by the door of the Sacristy.

|

|

Piero della Francesca, Flagellazione di Cristo (dettaglio, i tre astanti)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

[1] "The subject-matter of the stories illustrated by Piero is drawn from Jacopo de Voragine's "Golden Legend", a 13th century text that recounts the miraculous story of the wood of Christ's Cross. The story tells how Adam, on his deathbed, sends his his son Seth to Archangel Michael, who gives him some seedlings from the tree original sin to be placed in his father's mouth at the moment of his death. The tree that grows on the patriarch's grave is chopped down by King Solomon and its wood, which could not be used for anything else, is thrown across a stream to serve as a bridge. The Queen of Sheba, on her journey to see Solomon and hear his words of wisdom, is about to cross the stream, when by a miracle she learns that the Saviour will be crucified on that wood. She kneels in devout adoration. When Solomon discovers the nature of the divine message received by the Queen of Sheba, he orders that the bridge be removed and the wood, which will cause the end of the kingdom of the Jews, be buried. But the wood is found and, after a second premonitory message, becomes the instrument of the Passion. Three centuries later, just before the battle of Ponte Milvio against Maxentius, Emperor Constantine is told in a dream, that he must fight in the name of the Cross to overcome his enemy. After Constantine's victory, his mother Helena travels to Jerusalem to recover the miraculous wood. No one knows where the relic of the Cross is, except a Jew called Judas. Judas is tortured in a well and confesses that he knows the temple where the three crosses of Calvary are hidden. Helena orders that the temple be destroyed; the three crosses are found and the True Cross is recognized because it causes the miraculous resurrection of a dead youth. In the year 615, the Persian Kin Chosroes steals the wood, setting it up as an object of worship. The Eastern Emperor Heraclius wages war on the Persian King and, having defeated him, returns to Jerusalem with the Holy Wood. But a divine power prevents the emperor from making his triumphal entry into Jerusalem. So Heraclius, setting aside all pomp and magnificence, enters the city carrying the Cross in a gesture of humility, following Jesus Christ's example."

Fresco Cycle in the Cappella Maggiore of San Francesco, Arezzo | www.wga.hu

Piero della Francesca finished his fresco cycle with this story, but history of the True Cross did not stop.

At the end of the forth century A.D. St. Cyril of Alexandria left a description of the ceremony of the True Cross veneration on Good Friday in Jerusalem, when all the faithful assembled in the Chapel of the Cross, built on a site of Calvary. St. Cyril also left the important evidence, that relics of the True Cross were distributed all over the Christian world and were highly valued.

In 1187 the great Muslim warrior Saladin (Salah ed-Din Yusuf) defeated the Christian knights in the decisive battle at Karnei-Hattin (Horns of Hattin) in Galilee (territory of modern Israel) and ended the rule of Christians over the Holy Land forever. The True Cross, which the knights had taken out of its chapel in Jerusalem and brought with them into the battle, vanished. Its further destiny is unknown, but the fragments of the True Cross were kept through centuries as most precious gifts.

One of the relics of the True Cross found its way to Venice and the wonderful miracles, which it performed, were commemorated by different Venetian artists, specialists in narrative painting.

The Golden Legend, or Lives of the Saints, Volume Three

Three texts facilitated the spread of the legend of the Cross in the late Middle Ages: the Legenda Aurea of Jacobus de Voragine, the anonymous legendary titled Der Heiligen Leben, and a miracle play known as the Augsburger Heiligkreuzspiel.

[2]"Dating the Arezzo frescoes has for some time been a matter of dispute. The work was begun by Bicci di Lorenzo in 1447-48, but he became ill soon after and died in 1452. Piero, as already mentioned, could have started his work while Bicci was still alive. The written testimony from which we reduce that the frescoes were finished is dated as late as 1466, but by then they could have been finished for years. Fortunately, figurative references exist that allow us to narrow the gap between the 146('j text and the possible starting dates. In a Judgment of Solomon (now in Richmond, Virginia), by a Florentine master, which is dated c. 1460, there are echoes of the Arezzo fresco in the architectural forms, the shaping of the landscape and the oriental robes. In the frescoes of Santa Maria di Morrocco, near Tavernelle, finished before 1459 by a minor master (Giovanni di Francesco according to some critics, Giovanni di Piamonte according to others), there is an Annunciation which reworks many of the clements of Piero's own fresco of the subject, in particular the figure of God the Father who is copied almost stroke for stroke. Finally Giovanni di Francesco, who died in 1459, shows us that he knew of the Battle of Heraclius in his panel for Santa Croce which is now in the Casa Buonarroti.

Piero was in Rome on 16 October

1458, when they were installing the scaffolding for the frescoes he was to paint in the Vatican; there is no doubt that he had been there for some time.103 On 14 January 1455 he was summoned to Borgo within forty days to finish the Polyptych of the Misericordia.1°4 So the date gap narrows as we move towards 1452, the date of Bicci di Lorenzo's death."

Carlo Bertelli, Piero della Francesca, New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 1992, p. 22.

[3] Historical Background | "St. Francis of Assisi came to Arezzo in the early years of the 13th century where he found a city torn with internal strife. With one of his many miracles, Francis brought peace to the community and blessed it with the vision of a great golden cross spreading its arms across the sky. As a result, his friars were allowed to congregate in a small community outside the walls and preach their message of love and salvation. By the early fifteenth century, the Franciscan Friary had moved into town where it built an imposing church dedicated to its founder. The apse end, rebuilt after a fire, was awaiting decoration. It was the custom in such establishments – always in need of financial support – to lease out space within the buildings to families to use as burial grounds. This privilege brought the friars monetary contributions for upkeep and/or enhancements of paintings, sculpture, and other church furnishings. The chapels on either side of the main apse had already been painted in the late 14th century, but the chancel itself, the Cappella Maggiore, which had been leased to the local Bacci family, was still without decoration.

After complaints from the friars in the 1440s, the Bacci sons sold a vineyard and other real estate to acquire the cash to begin paying for a campaign of fresco painting. As was usual, the administrators of the church, the Franciscans, were the ones who chose the appropriate subject matter, in this case, a subject dear to St. Francis’s devotion, the Legend of the True Cross. The apocryphal narrative was set on the three vertical walls of the chapel, with paintings on the triumphal arch and the vault creating a scheme of redemption under the authority of Papal Rome. Bicci di Lorenzo, an aging artist from Florence, was hired. He and his workshop started at the top (frescos are always painted from the top down because of dripping), completing a scene of the Last Judgement high up on the entrance arch, and the four Evangelists on the webs of the ribbed vault. Apparently during this operation, in 1452 Bicci di Lorenzo grew ill and returned to Florence where he died. Members of his shop continued the work for a short while, painting most of the decorations of the ribs and other structural members and at the least, two standing figures of the four Fathers of the Church that are just below the vault. Then they too left Arezzo. Only after this sequence of events was Piero della Francesca called in to complete the project."

Lavin, M. A., et al., Piero della Francesca On-line: Story of the True Cross, San Francesco, Arezzo (Italy). In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Museums and the Web 2009: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2009 | www.archimuse.com

[4] The Battle of the Milvian Bridge took place between the Roman Emperors Constantine I and Maxentius on 28 October 312. Constantine won the battle and started on the path that led him to end the Tetrarchy and become the sole ruler of the Roman Empire. Maxentius drowned in the Tiber during the battle.Constantine reached Rome at the end of October 312 approaching along the Via Flaminia. He camped at the location of Malborghetto near Prima Porta, where remains of a Constantinian monument in honour of the occasion are still extant.

Events of the battle

It was expected that Maxentius would remain within Rome and endure a siege, as he already had successfully employed this strategy during the invasions of Severus and Galerius. He had already brought large amounts of food to the city in preparation. Surprisingly, he decided otherwise and met Constantine in open battle. Ancient sources about the event attribute this decision either to divine intervention (e.g., Lactantius, Eusebius) or superstition (e.g., Zosimus). They also note that the day of the battle was the same as the day of his accession (28 October), which was generally thought to be a good omen. Lactantius also reports that the populace supported Constantine with acclamations during circus games, though it is not clear how reliable his account of the events is.

Maxentius chose to make his stand in front of the Milvian Bridge, a stone bridge that carries the Via Flaminia road across the Tiber River into Rome (the bridge stands today at the same site, somewhat remodelled, named in Italian Ponte Milvio or sometimes Ponte Molle, soft bridge). Holding it was crucial if Maxentius was to keep his rival out of Rome, where the Senate would surely favour whoever held the city. As Maxentius had probably partially destroyed the bridge during his preparations for a siege, he had a wooden or pontoon bridge constructed to get his army across the river. The sources vary as to the nature of the bridge central to the events of the battle. Zosimus mentions it, vaguely, as being a wooden construction others specify that it was a pontoon bridge; sources are also unclear as to whether the bridge was deliberately constructed as a collapsible trap for Constantine's forces or not.

The next day, the two armies clashed, and Constantine won a decisive victory. The dispositions of Maxentius may have been faulty as his troops seem to have been arrayed with the River Tiber too close to their rear, giving them little space to allow re-grouping in the event of their formations being forced to give ground. Already known as a skillful general, Constantine first launched his cavalry at the cavalry of Maxentius and broke them. Constantine's infantry then advanced, most of Maxentius's troops fought well but they began to be pushed back toward the Tiber; Maxentius decided to retreat and make another stand at Rome itself; but there was only one escape route, via the bridge. Constantine's men inflicted heavy losses on the retreating army. Finally, the temporary bridge set up alongside the Milvian Bridge, over which many of the troops were escaping, collapsed, and those men stranded on the north bank of the Tiber were either taken prisoner or killed. Maxentius' Praetorian Guard seem to have made a stubborn stand on the northern bank of the river. Maxentius was among the dead, having drowned in the river while trying to swim across it in a desperate bid to escape or, alternatively, he is described as having been thrown by his horse into the river. Lactantius describes the death of Maxentius in the following manner: "The bridge in his rear was broken down. At sight of that the battle grew hotter. The hand of the Lord prevailed, and the forces of Maxentius were routed. He fled towards the broken bridge; but the multitude pressing on him, he was driven headlong into the Tiber."

From The Battle of the Milvian Bridge - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

[5] Sylvia Ronchey, L'enigma di Piero. L'ultimo bizantino e la crociata fantasma nella rivelazione di un grande quadro, Milano, Rizzoli, 2006"(...)

[6] Perhaps initially Piero did not believe he would continue the decoration of the chapel and so he limited himself to completing the parts left unfinished, respecting completely the decorative structure of the aging master. To complete Bicci di Lorenzo's unfinished work Piero painted a fascinating angel's head, within a quatrefoil frame. This is the angel that would later look on the scene of the Death of Adam. The other missing angel he left to an assistant, identified as Giovanni di Piamonte."

Carlo Bertelli, Op. cit., p. 79.

|

|

Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists | Piero della Francesca

Wikimedia Commons | Frescos by Piero della Francesca in San Francesco (Arezzo)

The interactive website, Piero della Francesca: The Legend of the True Cross was created by the department of Art History at Princeton and allows the viewer to move through the chapel’s space and experience Piero Della Francesca’s fresco cycle of medieval legends from many different vantage points. The user can follow the narrative chronologically, view the frescoes in detail, and notice thematic connections teased out by the images’ relationship in space. The application is fully available on the Internet Explorer browser.

Navigate the Model (Internet Explorer Only)

Art in Tuscany | The Golden Legend (Legenda aurea or Legenda sanctorum)

Church of San Francesco, Fresco cycle of the Legend of the True Cross, the official site | www.pierodellafrancesca.it

Fresco Cycle in the Cappella Maggiore of San Francesco, Arezzo | www.wga.hu

Piero della Francesca and the Italian Courts - Exhibition 2007 in Arezzo

Piero della Francesca Foundation

George W. Hart, Piero della Francesca's Polyhedra

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Bibliography

Jan Willem Drijvers, Helena Augusta: The Mother of Constantine the Great and the Legend of Her Finding of the True Cross, Brill Academic Publishers, 1997

Lavin, M.A. , Piero della Francesca. London, Phaidon Press, 2002

Carlo Bertelli, Piero della Francesca: The Frescoes of San Francesco in Arrezzo, Skira, 2002

Carlo Bertelli, Piero della Francesca, New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 1992

Carlo Bertelli, Antonio Paolucci, Piero della Francesca e le corti italiane (Catalogo della mostra (Arezzo, 31 marzo - 22 luglio 2007), Milano, Skira Editore, 2007

J.V. Field, Piero della Francesca: A Mathematician's Art, New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 2005

John Pope-Hennessy, The Piero Della Francesca Trail, Little Bookroom, 2002

|

|

|

Sources

CLARK, Kenneth, Piero della Francesca, London, Oxford, New York, 1951; VECCHI, Pierluigi de, L'Opera completa di Piero della Francesca, Rizzoli Editore, Milano, 1967; ANGELINI, Alessandro, Piero della Francesca, Scala/Riverside, New York, 1985

|

|

|

Holiday homes in the Tuscan Maremma | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia is embedded in the tranquility of the Tuscan country and let you enjoy great views of the Maremma,

the coast and Monte Christo, Santa Pia is off the beaten track and is the ideal choice for those seeking a peaceful, uncontaminated environment.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Siena, Piazza del Campo

|

|

Orbetello |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Arezzo |

|

Perugia |

|

Sansepolcro |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The façade and the bell tower of

San Marco in Florence |

|

Piazza della Santissima Annunziata

in Florence |

|

Monte Christo, view from Santa Pia |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]()