| |

|

The painting was executed between 1472 to 1474. The former date is based on a document of the Monastery of San Bernardino, where the painting was originally located, which stated that it had been executed by Fra Bartolomeo Carnevale of Urbino by that date; the latter is confirmed by the absence from Federico's figure of the insigna of the Garter, which he received in that year. The attribution to Fra Carnevale (Bartolomeo di Giovanni Corradini) is today rejected by all art historians.

Some sources state that the work was commissioned for to celebrate the birth of Federico's son, Guidobaldo, who was born in 1472. According to this hypothesis, the Child could represent Guidobaldo, while Virgin may have the appearance of Battista Sforza, Federico's wife, who died in the same year and was buried at San Bernardino.

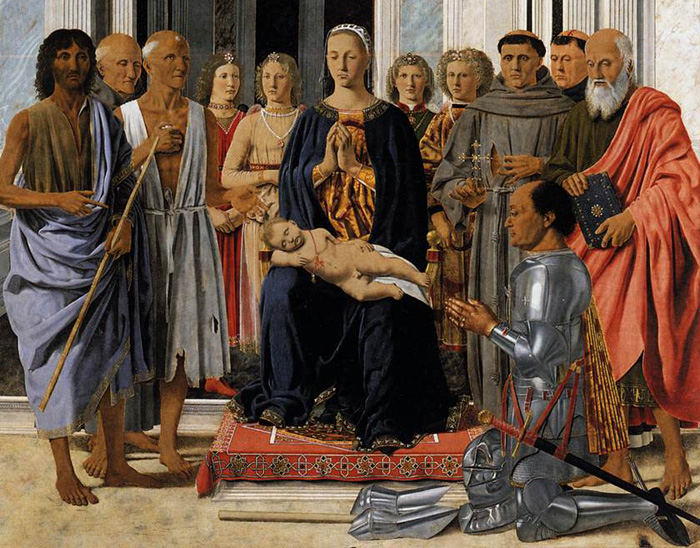

The work represents a sacra conversazione,[1] with the Virgin enthroned and the sleeping Child in the middle, surrounded by a host of angels and saints. On the right low corner, kneeling and wearing his armor, the Duke, patron of arts and condottiero Federico da Montefeltro. The background consists of the apse of a church in Renaissance classical style.

The Child wears a necklace of deep red coral beads, a color which alludes to blood, a symbol of life and death, but also to the redemption brought by Christ. Coral was also used for teething, and often worn by babies. The saints at the left of the Madonna are generally identified as John the Baptist, Bernardino of Siena (dedicatee of the paintings's original location) and Jerome; on the right would be Francis, Peter Martyr and Andrew. In the last figure, the Italian historian Ricci has identified a portrait of Luca Pacioli, a mathematician born in Sansepolcro like Piero della Francesca.[2] The presence of John the Baptist would be explained as he was the patron saint of Federico's wife, while St. Jerome was the protector of Humanists. Francis, finally, would be present as the painting was originally thought for the Franciscan church of San Donato degli osservanti, where Federico was later buried.

The characters' clothes, the angels' jewells, Federico's armor and the oriental carpet beneath the feet of the Virgin are depicted in great detail, reflecting the influence of Early Netherlandish painting.

The apse ends with a shell semi-dome from which an ostrich egg is hanging. The shell was a symbol of the new Venus, Mary (in fact it is perpendicular to her head) and of eternal beauty; in fact, differently from the Greek goddess, Mary's beauty will remain eternal in the Kingdom of God. According to another hypothesis, the egg would be a pearl, and the shell would refer to the miracle of the Immaculate conception (the shell generates the pearl without any male intervention). The egg is generally considered a symbol of the Creation and, in particular, to Guidobaldo's birth; the ostrich was also one of the heraldic symbols of the Montefeltro family. Federico da Montefeltro, shown kneeling at the foot of the Madonna's throne, is portrayed in his warrior's armour, but without the insignia awarded to him by Pope Sixtus IV in 1475. The absence of these emblems, which Piero would certainly have included in an official portrait like this one, leads us to date the splendid Brera altarpiece, previously believed to be Piero's last work, at around 1472-74.

According to Italian art historian Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti, the work has been cut down on both sides, as shown by the portions of entablatures barely visible in the upper corners.

|

|

|

A mysterious ostrich egg hovers above, the way the dove hovered over Christ in the Baptism. Such an egg often hangs over alters dedicated to the Virgin. It was believed that the ostrich let her egg hatch in the sunlight without intervention, and thus became a symbol of virgin birth. Also, the ostrich is here an absent mother, a symbol of the deceased Battista.

The complex and majestic architectural background, against which the 'sacra conversazione' takes place, is clearly derived from designs very similar to the ones followed by Alberti in his construction of the church of Sant'Andrea in Mantua. Yet, at the same time, the architecture anticipates certain 'classical' elements which will be used by the young Bramante - another extraordinary artist from Urbino. In this painting, too, the artist's mastery of proportions is remarkable; it is almost symbolized by the large ostrich egg hanging from the shell in the apse. The shape of this symbolic element is echoed by the near perfect oval of the Madonna's head, placed in the absolute centre of the composition. In this painting Piero places his vanishing point at an unusually high level, more or less at the same height as the figures' hands, with the result that his sacred characters, placed in a semicircle, appear less monumental.

Piero's extraordinary invention of an architectural apse echoed below by another apse, consisting in the figures of the saints gathered around the Madonna, was taken up time and again by artists working at the end of the 15th century and at the beginning of the 16th, particularly in Venice, starting with the almost contemporary paintings of Antonello da Messina and Giovanni Bellini. This organized composition, typical of Piero's work, contained within a unity of space and lighting, seems however to have a new feel about it, as though the artist were taking part in the new currents being developed in Italian art after 1470. The new trends are dictated primarily by the great popularity that Netherlandish painting was enjoying, particularly in Urbino. The most descriptive and 'miniaturistic' aspects of Netherlandish painting are echoed in the Brera altarpiece in the Duke's shining armour, for example, and in the stylized decoration of the carpet. Netherlandish art was popular among the patrons of the period as well, as we can see by the rings on Federico's hands, which Piero had painted by Pedro Berruguete, a Spaniard with a Northern training. |

|

|

|

The other aspect of this painting that must not be underestimated is its similarity with the new developments of Florentine painting, visible primarly in the work of Verrocchio and some of his young pupils. The angels' garments are decorated with jewels and with huge precious brooches, their hair is held back by elegant diadems: these elements, and even their melancholy expression, are certainly influenced by the recent developments in Florentine art. In the same way, St. John the Baptist's and St Jerome's bony limbs, emaciated by deprivations in the wilderness, recall some of Verrocchio's studies; and the sleeping Child, in his extraordinary contorted position, anticipates some of the young Leonardo's drawings of putti.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Itinerary in Central Italy | In the footsteps of Piero della Francesca

|

|

|

[1] In art, the Sacred conversation, sacra conversazione (the Italian original), or "Holy conversation" refers to a depiction of the Virgin and Child (the Virgin Mary with the infant Jesus) amidst a group of saints in a relatively informal grouping, as opposed to the more rigid and hierarchical compositions of earlier periods. The form developed during the Italian Renaissance as artists replaced earlier hieratic triptych or polyptych formats with compositions in which figures interacted within a unified perspectival space. Early examples are one by Fra Angelico and another by Filippo Lippi. Among other artists to depict such a scene are Piero della Francesca, Giovanni Bellini, Paolo Veronese, and Andrea Mantegna.

|

|

|

[2] It has been conjectured that the figure second from the right is Luca Pacioli. He was the author of the book Summa de Arithmetica, Geometrica, Proportioni et Proportionialitate (1478), best known for its account of double entry book-keeping, and of De Divina Proportione (1509), in which are found images of regular polyhedra attributed to Leonardo.

Luca Bartolomes Pacioli (c.1445-1517) was a renowned mathematician, captivating lecturer, teacher, prolific author, religious mystic, and acknowledged scholar in numerous fields. He was a link between the Early Renaissance of Piero della Francesca and the High Renaissance of Leonardo. Luca Pacioli and Piero della Francesca were both born in Sansopolcro, and Luca was tutored in mathematics by Piero. Luca even posed for Piero in the mid 1470's for Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels, in which Pacioli portrays St. Peter Martyr, with cut head symbolizing his assassination.

Piero della Francesca had two passions - art and geometry. He sought that link between an organic and geometric basis of beauty, what Kenneth Clark has called the Philosopher's stone of aesthetics. Twenty years before his death in 1492, Piero is said to have given up his highly successful career in painting and devoted himself entirely to mathematics. This may have been due to failing sight. Vasari says that Piero went blind at about age 60, (c.1480). It was during this period that he wrote three books, De Prospectiva pingendi (c.1474), Trattato del abaco, and De quinque corporibus regularibus, described by Plato in his Timaeus.

De quinque corporibus regularibus was never published but was placed in the library of Federigo da Montefeltro, seen kneeling in this painting. Unfortunately the work was plagiarized by Luca Pacioli.

|

|

Detail showing Pacioli (in the middle)

Detail showing Pacioli (in the middle) |

|

|

![]()