Duccio di Buoninsegna | Maestà Altarpiece (1308-1311) | Back Panels of the Maestà |

The Sienese School of painting flourished in Siena, Italy between the 13th and 15th centuries. Duccio's role in the development of early Sienese painting may be equated roughly with the roles of both Cimabue and Giotto in the development of Florentine painting. In Duccio’s art the formality of the Italo-Byzantine tradition, strengthened by a clearer understanding of its evolution from classical roots, is fused with the new spirituality of the Gothic style. Greatest of all his works is the Maestà (1311), the altarpiece of the Siena cathedral. |

|

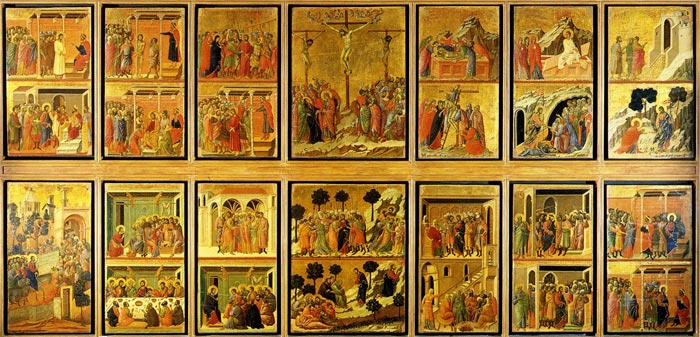

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maesta Altarpiece(verso), Stories of the Passion, 1308-11, tempera on wood, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena |

The main element of the back consisted of fourteen panels, originally separated by little columns or pilasters (of about 4 cm) which were lost, together with the outside frame, in the dismembering of 1771.

|

|

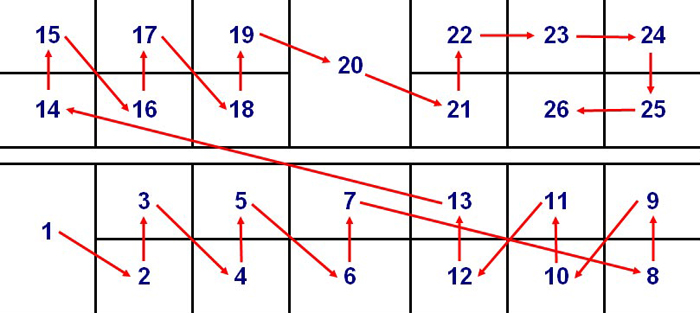

The episodes on the reverse side were intended for spectators in the presbytery, who could get closer to the panel than the faithful who congregated in the main body of the church. The central section, with 26 scenes from Christ’s Passion, represents the most comprehensive Passion cycle, which has survived. In contains stories from all four Gospels. The sequence of pictures now offered in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo may not be correct. The series undoubtedly begins, however, at the bottom left with The Entry into Jerusalem. Stories of the Passion |

Reading scheme of the reverse |

|

| It is interesting to note the different function of the scenes represented on the two sides of the Maestà. The front side was a devotional image destined for the community of the faithful (which explains its size, clearly visible from every corner of the church), while the back was essentially a narrative cycle intended for the closer observation of the clergy in the sanctuary. The main element of the back consisted of fourteen panels, originally separated by little columns or pilasters (of about 4 cm) which were lost, together with the outside frame, in the dismembering of 1771. Except for the Entry into Jerusalem and the Crucifixion, each panel contains two episodes. The central part of the lower row with the Agony in the Garden and Christ taken Prisoner is twice as wide as the other compartments (but the same as the Crucifixion panel) because the events portrayed are composed of different narrative units. Numerous contrasting theories have been advanced by critics for the order of interpretation, rendered problematical by the variety of New Testament sources drawn on by Duccio. It is certain that the cycle began at the bottom left and ended at the top right, proceeding from left to right first on the lower row and then on the upper. |

||

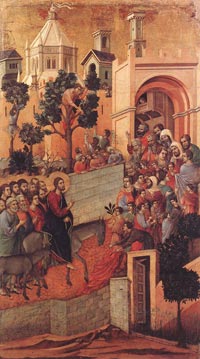

1 Entry into Jerusalem |

||

The scene is unusual because of the attention given to the landscape, which is rich in detail. The paved road, the city gate with battlements, the wall embrasures, the slender towers rising up above and the polygonal building of white marble reproduce a remarkably realistic layout, both urbanistically and architecturally. The small tree, withered and leafless, that shows behind Christ's halo, is the fig-tree that Christ found without fruit. Florens Deuchler has suggested that the literary source is a historical work of the first century A.D., the De Bello Judaico by Flavius Josephus which was well-known in the Middle Ages. The panel by Duccio is a faithful reproduction of the description of Jerusalem in Book V. Infrared photography during restoration has revealed several changes of mind regarding the area around the tree in the centre and the road. The small tree, withered and leafless, that shows behind Christ's halo, is the fig-tree that Christ found without fruit. Christ Entering Jerusalem is the final visit to the city, described by all four evangelists: Matthew 21:1-11; Mark 11:1-10; Luke 19:29-38; John 12:12-15. |

||

2 The Last Supper |

||

The Last Supper is dominated by the central figure of Jesus who, to the astonishment of the onlookers, is offering bread to Judas Iscariot (shown in other panels with the same features). An unusual experiment with space has been made with John, whose position is traditional: the head of the favourite disciple is painted in front of the figure of Christ, and his halo behind Christ's shoulders. Wooden bowls, knives, a decorated jug and a meat dish, and the paschal lamb, are set on the table, which is covered with a simple tablecloth woven in a small diamond pattern. |

||

3 Washing of the Feet |

||

Only John tells the story of the Washing of the Feet and the events should therefore be read from the top downwards, according to the order in which they occur in this gospel. The setting is the interior, in central perspective, of an unadorned room; the only decorative elements are the coffered ceiling and the multifoiled insert placed on the rear wall. This detail must also be imagined in the Last Supper, hidden by Christ's halo, since it reappears in Christ Taking Leave of the Apostles, which according to the gospel occurs in the same place. Echoes from Byzantine art can be seen in the Washing of the Feet, in the crowded throng of the apostles and Peter's gesture, while Christ's position recalls Western models. The shape of the black sandals, aptly described by Cesare Brandi "as if they were precious onyx scarabs", is typical. |

||

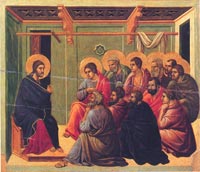

4 Christ Taking Leave of the Apostles |

||

Following the story in John again, the scenes succeed each other from the bottom upwards although occurring simultaneously. While Jesus is giving the new commandment to the apostles (now eleven) , Judas betrays him for thirty pieces of silver. In Christ Taking Leave of the Apostles, his sideways position, shown up by the half-open door, is in contrast to the closeknit group of disciples. They are all turning the same way in thoughtful attitudes, the soft drapery of their coloured robes animating the whole scene. As in the Washing of the Feet and the Last Supper Duccio has avoided haloes since the conspicuous shape of the golden discs might have created an overpowering effect, besides taking up most of the space in the picture. |

|

|

5 Pact of Judas |

||

The Pact of Judas is set in external surroundings where the space is arranged in varying degrees of depth. The group in the foreground, on the same level as the pillar on the right, is gathered in front of a loggia with cross-vaults and round arches. The polygonal tower, a little behind the central building, completes the background. |

|

|

6 Agony in the Garden |

||

In the Agony in the Garden, Jesus is turning to Peter, James the Great and John, shaking them and warning them not to fall into temptation, while the other disciples are sleeping. On the right, in accordance with the Gospel of St Luke, which is the only one to mention an angel appearing, he withdraws in prayer. In this quiet setting, both episodes are visualized through the gestures of Christ, Peter and the angel. On the right, in accordance with the Gospel of St Luke, which is the only one to mention an angel appearing, Christ withdraws in prayer. |

||

7 Christ Taken Prisoner |

||

The Mount of Olives becomes the scene of unexpected agitation in Christ Taken Prisoner, containing three separate episodes: in the centre the kiss of Judas, to the left Peter cutting off the ear of the servant Malchus, to the right the flight of the apostles. The dramatic intensity of the scene, heightened by the crowded succession of spears, lanterns and torches, shows in the excited movements of the characters and the expressiveness of their faces. The landscape, after long being an anonymous feature of minor importance, takes on a new scenic role. The vegetation and rocky crags of Byzantine inspiration seem to be an integral part of the action: in the Agony in the Garden the three trees on the right isolate Christ, while in Christ Taken Prisoner they enclose the main episode, as if allowing the disciples to escape. |

||

| On the left Peter is cutting off the ear of the servant Malchus, on the right side of the scene: the flight of the apostles. |

|

|

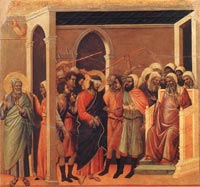

| 8 Pilate's First Interrogation of Christ |

||

As in the gospel, the group of Pharisees, animated by lively gestures (again the hand with pointing finger), is depicted outside the building: the Jews avoid going inside in order not to be defiled and to be able to eat the Passover meal. |

||

| 9 Christ Accused by the Pharisees |

||

| The surroundings for the scenes in which Pilate appears (Christ Accused by the Pharisees and Pilate's First Interrogation of Christ) are new since the events take place in the governor's palace. The slender spiral columns of white marble and the decoration carved along the top of the walls seem to refer to classical architecture. Pilate too, portrayed with the solemnity of a Roman emperor and crowned with a laurel wreath, evokes the world of classical antiquity. It is interesting to note how the latter's face still bears the slashings caused by medievalreligious fervour. The function of the beams placed on the capitals supporting a light and apparently unstable wooden roof is harder to explain.

As in the gospel, the group of Pharisees, animated by lively gestures (again the hand with pointing finger), is depicted outside the building: the Jews avoid going inside in order not to be defiled and to be able to eat the Passover meal. In the upper scene, an overwhelming aura of solitude surrounds Christ. |

||

| 10 Christ Before Caiaphas |

||

| According to the Gospel of St. Matthew, the compartment should be read from the bottom upwards. The scenes Christ before Caiaphas and Christ Mocked take place in the same surroundings, the lawcourt of the Sanhedrin, where Christ is brought before the High Priest Caiaphas and the Elders. In Christ Before Caiaphas, great importance is given to the person with raised hand and pointing finger looking significantly at the onlooker; the affronted gesture, isolated among a crowd of helmets and anonymous faces, catches the attention of the viewer. Caiaphas too is depicted in an attitude of wrath and indignation at the words of Jesus: with his hands on his breast he tears his red robes, showing the tunic underneath (this detail is told by Matthew and Mark). Gestures are more agitated in the scene above where Christ blindfolded (according to the version in Mark and Luke) and immobile in his dark cloak, is mocked and beaten by the Pharisees. |

|

|

| 11 Christ Mocked |

||

| This scene depicts the response of the servants and soldiers co the death-sentence which the wise men and scribes have passed on Jesus. The accused, who stands there motionless and blindfolded, becomes the target of blows and attacks. Above the entrance arch we now notice the cock, which crows as St. Peter addresses the woman servant, denying for the third time that he is a follower of Jesus.

|

||

12 Christ Accused by the Pharisees |

||

| The rule of absolute autonomy being given to each single scene is successfully broken in this panel. The two episodes, told by John, occur simultaneously but in different places and the stairs, a material link in space, also connect the time-factor. While Jesus is brought before the High Priest Annas, Peter remains in the courtyard where a servant-girl recognizes him as a friend of the accused: his raised hand indicates the words of denial. The surroundings are full of vivid architectural detail: the doorway with a pointed arch opening onto the room with a porch, the Gothic window of the small balcony, the pilaster strips on the back wall of the upper floor and the coffered ceiling, this time with smaller squares. Peter, whose halo in a curious fashion includes the head and shoulders of the person next to him, is warming his feet at the fire in a highly realistic manner. Lastly, because of her vertical position and arm resting on the handrail, the figure of the serving-maid about to go up the stairs was evidently the cause of much indecision since several "changes of mind" have been discovered around the skirt. | ||

| 13 Pilate's First Interrogation of Christ |

||

| The surroundings for the scenes in which Pilate appears (Christ Accused by the Pharisees and Pilate's First Interrogation of Christ) are new since the events take place in the governor's palace. The slender spiral columns of white marble and the decoration carved along the top of the walls seem to refer to classical architecture. Pilate too, portrayed with the solemnity of a Roman emperor and crowned with a laurel wreath, evokes the world of classical antiquity. It is interesting to note how the latter's face still bears the slashings caused by medievalreligious fervour. The function of the beams placed on the capitals supporting a light and apparently unstable wooden roof is harder to explain.

As in the gospel, the group of Pharisees, animated by lively gestures (again the hand with pointing finger), is depicted outside the building: the Jews avoid going inside in order not to be defiled and to be able to eat the Passover meal. |

||

| 14 Christ Before Herod |

||

| Pilate, on learning that Jesus belonged to the jurisdiction of Herod, sent the prisoner to the king to be judged by him. After questioning Jesus and treating him with ridicule and contempt, Herod sent him back to the Roman governor dressed in a conspicuous garment, the white robe that distinguished lunatics. Action proceeds from the bottom upwards; in the lower scene a servant is holding out to Christ the robe which in the upper scene he is already wearing. | ||

| 15 Christ Before Pilate Again |

||

| Pilate, on learning that Jesus belonged to the jurisdiction of Herod, sent the prisoner to the king to be judged by him. After questioning Jesus and treating him with ridicule and contempt, Herod sent him back to the Roman governor dressed in a conspicuous garment, the white robe that distinguished lunatics. Action proceeds from the bottom upwards; in the lower scene a servant is holding out to Christ the robe which in the upper scene he is already wearing. Although placed in different architectural surroundings (the governor's palace present in the last compartment on the lower row appears again), the arrangement of the two scenes is almost identical, both in the distribution of the characters and in their movements. Christ, gazing with extreme sadness at the onlooker, is withdrawn in total silence. Herod anticipates and repeats (Pilate's First Interrogation of Christ) the position of Pilate where the solemn movement gives a rather static effect. The king's throne with steps, its basic structure embellished and adorned, is more ornate than the governor's simple wooden seat. | ||

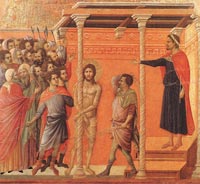

| 16 Crown of Thorns | ||

| 17 The Flagellation |

||

| Considering that the Flagellation is barely mentioned in the gospels, the descriptive details show remarkable inventiveness, aimed at illustrating each moment of the Passion. The figure of Pilate disobeys all the rules of perspective: although obvious from the seat on which he is standing that he is inside the building, he manages to stretch his arm in front of the pillar, in a position parallel to the horizontal level of the floor.Cimabue appears to have been a highly-regarded artist in his day. While he was at work in Florence, Duccio was the major artist, and perhaps his rival, in nearby Siena. History has long regarded Cimabue as the last of an era that was overshadowed by the Italian Renaissance. In Canto XI of his Purgatorio, Dante laments Cimabue's quick loss of public interest in the face of Giotto's revolution in art:[3] O vanity of human powers,

|

||

Reading scheme of the reverse |

||

Bibliography The Art of the Italian Renaissance. Architecture. Sculpture. Painting. Drawing. Könemann. 1995. |

||

[1] Duccio di Buoninsegna (c. 1255-1260 – c. 1318-1319) was one of the most influential Italian artists of his time. Born in Siena, Tuscany, he worked mostly with pigment and egg tempera and like most of his contemporaries painted religious subjects. He influenced Simone Martini and the brothers Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti, among others. His works include the Rucellai Madonna (1285) for Santa Maria Novella (now in the Uffizi) and the fabled Maestà (1308–11), his masterpiece, for Siena's cathedral. The centre of the Maestà depicts the Virgin and Child enthroned and surrounded by angels and saints. He also painted a work known as the Stoclet Madonna, the name stemming from its previous ownership by Stoclet in his collection in Brussels. The Madonna, painted on a wooden panel around the year 1300, was purchased in November 2004 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City for an estimated sum of 45 million USD, the most expensive purchase ever by the museum. In 2006 James Beck, a scholar at Columbia University, stated that he believes the painting is a nineteenth century forgery; the Metropolitan Museum's curator of European Paintings has disputed Beck's assertion. [2] |

||||

|

||||

Holiday accomodation in Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

||||

Podere Santa Pia |

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, December |

View from terrace with a stunning view over the Maremma and Montecristo |

||

Siena, Palazzo Publico |

Siena, Duomo |

Val d'Orcia |

||