| |

|

Built in 1290, the cathedral at Orvieto, Italy, is a masterpiece of Italian gothic architecture. The decoration of the Cappella Nuova, commenced by Fra Angelico in 1447 and magnificently completed by Luca Signorelli in 1499 and 1504, displays an awe-inspiring Last Judgement and Apocalypse and, below it, scenes from Dante and classical literature.

The frescoes depicting the Last Judgment in the S. Brizio Chapel of the Cathedral in Orvieto are Signorelli's masterpiece. Called to Orvieto in 1499 to complete the vault decorations begun by Fra Angelico and Benozzo Gozzoli, Signorelli worked until 1504 painting the walls with a vivid narrative, including the Preaching of the Antichrist, the End of the World, the Resurrection of the Dead, and the Damned and the Elect. He suppressed details of environment to concentrate attention on the numerous nude figures that dominate the compositions. These frescoes, which Vasari claimed Michelangelo admired, were the most compelling depiction of the Last Judgment before Michelangelo's great fresco in the Sistine Chapel.

A major monument, Luca Signorelli's Orvieto Cathedral frescoes rendered with vigor and invective the most ambitious consideration of the Apocalypse and the Last Judgment in Italian Renaissance art. IBegun by Fra Angelico in 1447 and completed by Signorelli at the turn of the century, the frescoes reflect the turmoil within the Papal States, the suffering brought on by a surge of natural disasters, the fear of the Turks, and the anti-Judaic campaigns of the day.

At the close of the 15th century, Orvieto experienced a series of events which presaged evidence of divine displeasure. Terrible rainstorms, plague, civil strife, the threat of invasion, and appalling apparitions in the sky were seen as apocalyptic warnings. In that era of spiritual discomfort, the painter Luca Signorelli was commissioned to decorate the walls and vaults of the San Brizio Chapel in the Orvieto Cathedral.

|

|

Beato Angelico, Cristo Giudice (1447), Orvieto, Duomo, Cappella di San Brizio [5]

|

Fifty-two years before, in 1447, Fra Angelico had spent three months and a half in this Cathedral of Orvieto, painting the spandrels in the roof of the Cappella Nuova, as it was then called.[62] He had time to complete only two frescoes, being either recalled to Rome by Nicholas V., or to the convent of S. Domenico, near Fiesole (of which, in 1450, he was made Prior). These two works are among the best and strongest of his paintings

The sixteen prophets are shown seated, tier upon tier, in a tribune of judgment on Christs proper left side. The gothic ribbing of the vault was an almost insurmountable obstacle to the artists efforts to make a unified conception, and the necessity of arranging his figures inside triangular divisions is uncomfortably apparent. The rigidity of the prophets is slightly relieved by a certain amount of interaction within the group, especially among the nine that comprise the apex of the pyramid. The fresco mainly appeals for its luminous enamel-like colors, which have been liberated from much overpainting by the recent cleaning and restoration. In the corresponding vane on the other side of Christ, the Virgin is shown in the midst of the Apostles. This triangular section of fresco was deigned by Fra Angelico in the summer of 1447, but only painted by Luca Signorelli fifty years later. |

|

Fra Angelico, Sixteen Prophets, Chapel of Saint Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto

|

Signorelli's Orvieto frescos represent the most important forerunners to Michelangelo's Last Judgment. In those awe-inspiring frescos of the Apocalypse the artist reached the height of his development.

Luca Signorelli spent nearly the whole of his last twenty years in provinces, between Cortona and Citta di Castello. The painter died in 1423 in Cortona.

|

|

San Brizio Chapel in Orvieto Cathedral

San Brizio chapel was built at the beginning of the 15th century on the place of sacristy of the Orvieto Cathedral. The construction of this chapel was started in 1408 and completed in 1444. It is closed off from the rest of the cathedral by two wrought iron gates. Originally called the Cappella Nuova, or New Chapel, in 1622 this chapel was dedicated to San Brizio, one of the first bishops of Spoleto and Foligno, who evangelized the people of Orvieto. Legend says that he left them a panel of the Madonna della Tavola, a Madonna enthroned with Child and Angels.

The decoration of the chapel started in 1447 by Fra Angelico and Benozzo Gozzoli, who executed two compositions (Christ the Judge and Prophets) on the vaults. The commission was only revived at the end of the century. The painter Luca Signorelli was chosen thanks to his fame as a fast executor and because he took less money than other artists. Indeed, starting the work in April-May 1499 he finished it already in 1502, though the final payment was made only in 1504.

First Signorelli finished the decoration of the vaults. The frescos Angels with Emblems of Passions and the Apostles are believed to be fulfilled from the cardboards of Fra Angelico. Signorelli executed the compositions Martyrs and Virgins, Patriarchs and Doctors of the Church from his own sketches, though it's believed that he followed Fra Angelico's program. On April 23, 1500 the decoration of the vaults was finished, also the drawings for the wall paintings were evidently ready, because a few days later a new contract for wall frescos was signed.

The subject of the wall fresco cycle is Apocalypse and the Last Judgment. The work is entirely the product of Signorelli's powerful imagination, though, of course, he was influenced by literary sources - Gospels, Apocryphal Gospels, Golden Legend, and Dante's Divine Comedy. The cycle consists of six large compositions, each of them occupies the upper parts of the walls:

The Deeds of the Antichrist (on the left wall) opens the cycle.

Antichrist is supposed to come to the world before its end. In Signorelli's fresco the action takes place in an Italian city and quite possibly it reflected recent events – revolt and execution (May 23 1498) of Savonarola, who was condemned as Antichrist by the Church.

The End of the World (over the entrance)

The Resurrection of the Dead (on the right wall)

The Hell (on the right wall, next to the Resurrection)

The Last Judgment (on the altar wall) the composition is divided into two parts by the window: the Damned Consigned to Hell (left part) and the Blessed Consigned to Paradise (right part).

The Paradise, or Coronation of the Chosen (left wall, next to Antichrist)

The lower parts of the walls are executed as decorative panels.

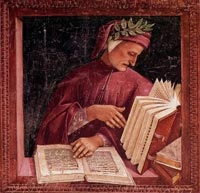

In the center of each panel is a portrait of a poet or a philosopher – Dante, Virgil, Ovid, Horace, Lucian, Homer and Empedocles. Each portrait is surrounded by four tondos with the scenes from their works, painted in monochrome. Quite possible that the lower parts were executed by Luca's apprentices by his sketches.

|

|

Decorative scheme of the Cappella Nuova; north side

|

| Luca Signorelli, on 5 April 1499, signed a contract with Orvieto Cathedral. He was to paint the two remaining sections of the ceiling of the Chapel of San Brizio, a large Gothic construction built around 1408. In the summer of 1447 Fra Angelico, assisted by Gozzoli and several other minor artists, had painted a fresco of the Prophets in one of the triangular ceiling vanes and Christ the Judge in another. Half a century later Signorelli's task was to complete the fresco decoration begun by Angelico. The administrators of the Cathedral had asked other artists before Signorelli, including Perugino and Antonio da Viterbo, called Il Pastura. They finally decided to hire Luca both because he had asked for less money and because he had a reputation for being more efficient and faster than other artists. The contract refers to him as the artist who had painted 'multas pulcherrimas picturas in diversis civitatibus et presentim Senis' (many beautiful paintings in different cities and especially in Siena).

Signorelli respected the terms of the contract and worked at such a speed that even the Cathedral administrators must have been surprised. A year after the contract was signed, on 23 April 1500, the ceiling frescoes were finished and he was able to show his patrons his drawings for the side wall frescoes. The contract for these further paintings was signed a few days,later: he was to be paid 575 ducats for this second part. In 1502 the fresco cycle was certainly finished, although further payments to Signorelli are recorded as late as 1504.

In only three years, from 1499 to 1502, the decoration was planned and executed, with a speed and efficiency that is practically unique in the history of Italian art. As far as the subject matter is concerned, it is one of the most important subjects of Christian iconography. It is likely that for the ceiling frescoes (the groups of Apostles, Angels, Prophets, Patriarchs, Doctors of the Church, Martyrs and Virgins) Signorelli simply completed the programme that had originally been devised by Fra Angelico. But the frescoes on the side walls, although the basic subject would have been planned in accordance with the Cathedral's administrators and theologians, are wholly the product of Signorelli's fertile imagination. The side walls are covered with seven large scenes:

* the Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist,

* the Destruction of the World,

* the Resurrection of the Flesh,

* the Damned,

* the Elect,

* the Paradise,

* the Hell.

The lower part of the walls is decorated with grotesque patterns and with busts of philosophers and poets alongside monochromes commenting their works, as well as illustrations from the Divine Comedy. The overall decoration is completed in the jambs of the windows and in the small chapel on the far wall by the figures of Archangels Raphael (with Tobias), Gabriel and Michael (weighing souls and subjugating the devil), by Bishop Saints Brizio and Constant, and the Lamentation over the Dead Christ with Saints Parenzo and Faustino.

Vasari says that "Luca's works were highly praised by Michelangelo" and several instances of close similarity between the work of the two men can be cited.

|

|

| Decorative scheme of the Cappella Nuova; south side [4] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist

|

|

|

|

Luca Signorelli, Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist (detail), 1499-1502, fresco, Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto

|

The puritanical Dominican preacher Girolamo Savonarola assumed absolute control of Florence after the Medici fled the city following the death of Lorenzo de' Medici in 1492. Savonarola denounced humanism and encouraged "bonfires of the vanities," in which citizens were exhorted to burn classical texts, scientific treatises, and philosophical writings. Luca Signorelli's frescoes in the San Brizio Chapel includes the Damned Cast into Hell, where a dense writhing mass of humans are tortured by ferocious demons. Skillfully foreshortened nude, muscular bodies twist and turn in anguish and pain.

It is quite likely that the Deeds of the Antichrist is intended as a reference to Savonarola, the Dominican friar hanged and burnt at the stake in Florence on 23 May 1498. [0] With great ability Signorelli resolved the use of larges masses in this event depicting equally spaced distinct groups reaching an excellent sense of unity.

In a 'Papist' city like Urbino, and in the case of an artist like Signorelli who had been a Medici protégé and who thought of himself basically as a victim of persecution from the Florentine democratic government (a fact we learn from Michelangelo), this identification of Savonarola with the Antichrist is very plausible; it is also supported by a famous passage in Marsilio Ficino's Apologia, published in 1498, where the Ferrarese monk is again identified as the false prophet.

There is no doubt that Signorelli has given us a very convincing portrayal of the sinister and mysterious atmosphere evoked in the prophecies of the Gospels in the huge fresco showing the Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist. Against a vast and desolate background, dominated on the right by an unusually large classical building, depicted in distorted perspective, the false prophet is shown disseminating his lies and spreading his message of destruction. He has the features of Christ, but it is Satan (portrayed behind him) who tells him what to say. The people around him, who have piled up gifts at the foot of his throne, have clearly already been corrupted by the iniquities the Gospel has warned us of. And, starting from the left, we have a description of a brutal massacre, followed by a young woman selling her body to an old merchant, and then more aggressive and evil-looking men. In the background of this scene all sorts of horrors and miraculous events are taking place. The Antichrist orders people to be executed and even resurrects a man, while a group of clerics, huddled together like a fortified citadel, resist the devil's temptations by praying. Lastly, to the left, Signorelli shows us how the age of the Antichrist is rapidly reaching its inevitable epilogue, with the false prophet being hurled down from the heavens by the Angel and all his followers being defeated and destroyed by the wrath of God.

The Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist, is the masterpiece of the whole cycle (at least in terms of originality of invention and evocation of fantastic imagery) even Signorelli himself must have realized, and he has placed himself, together with a monk (traditionally identified as Fra Angelico) on the lefthand side of the composition. [1]

|

|

|

| |

The Deeds of the Antichrist (detail). Orvieto Cathedral, San Brizio Chapel, Orvieto |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

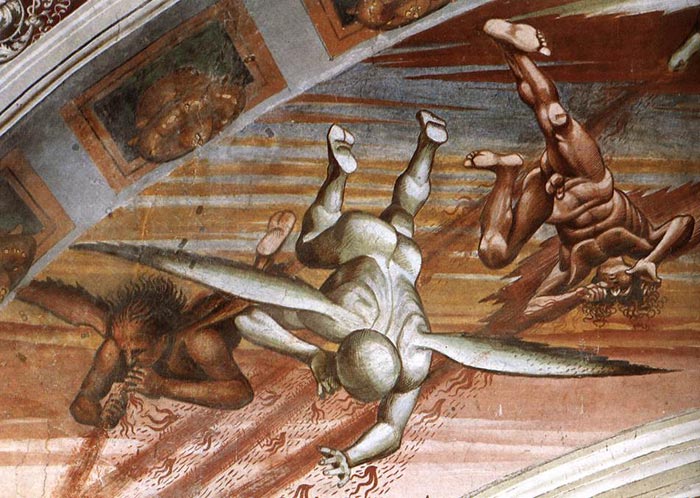

Luca Signorelli, Apocalypse (detail), 1499-1502, fresco, Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto

|

According to the prediction in the Scriptures, the deeds of the Antichrist take place immediately before the end of the world, in those last days when 'the sun shall be darkened, and the moon shall not give her light, And the stars of heaven shall fall, and the powers that are in heaven shall be shaken' (Mark, 13: 24-25).

For his description of the end of the world the artist had to make do with the narrow spaces on either side of the entrance door to the chapel. He was thus forced to divide the scene into two narrative sections. To the right he describes the first signs of the Apocalypse, which has been the object of prophecies since earliest times. In the foreground, in the lower part of the painting, he has shown King David and the Sibyl, as witnesses of Dies Irae. The stars go pale, fires and earthquakes sweep the earth, war and murder spread throughout the world. The lefthand section recounts the epilogue of this preannounced catastrophe. Demons looking like monstrous bats soar through the darkened sky, showering earth with flaming arrows; the last survivors fall under their shots, piling up on top of each other like broken dolls.

|

|

|

Luca Signorelli, Apocalypse (details), 1499-1502, fresco, Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto

|

|

|

|

|

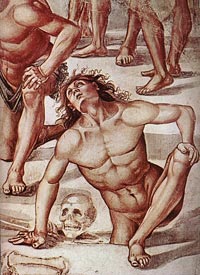

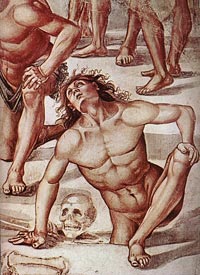

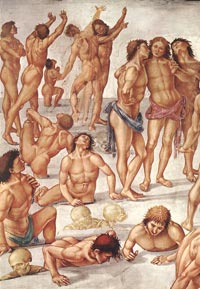

Resurrection of the Flesh

|

|

|

|

Luca Signorelli, Resurrection of the Flesh (detail), 1499-1502, fresco, Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto

|

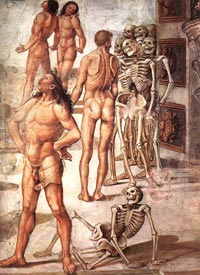

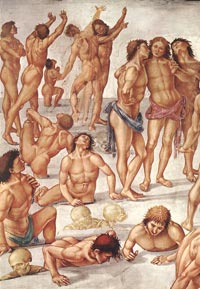

The account of the Apocalypse then continues with three large scenes, the Resurrection of the Flesh, the Damned and the Elect, and two smaller ones on either side of the chapel's window, Paradise and Hell.

In the grand and dramatic scenes inspired by the Divine Comedy , he displayed a mastery of the nude in a wide variety of poses, surpassed at that time only by Michelangelo

It is primarily in this section of the fresco cycle that Signorelli has given free rein to his inventive genius. An inventiveness that, as Berenson said, made him one of the greatest of modern illustrators, and thanks to which his art is still an extremely important part of our figurative heritage. Despite the rhetorical devices, the theatrical ruses and the occasional contrived details, despite the limitations in his draughtsmanship and use of colour recognized by all modern critics, there is no denying that never before in Italian art had figurative ideas of such unforgettable power been used. Viewed all together the huge frescoes in the Orvieto chapel give an impression of overcrowding and of confusion which is far from pleasing. We have to isolate the individual details in order to grasp the greatness of Signorelli the 'illustrator' and the 'inventor' and therefore justify Berenson's statement. See, for example, in the Resurrection of the Flesh, the macabre but hilarious idea of the nude with his back to the observer who is carrying on a conversation with the skeletons; or the skulls surfacing through the cracks in the ground, who put on their bodies as though they were a costume, and become human beings once again.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Luca Signorelli, Resurrection of the Flesh (details), fresco in the Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

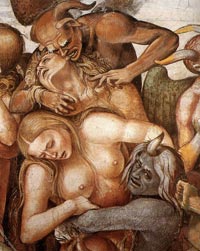

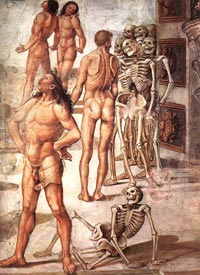

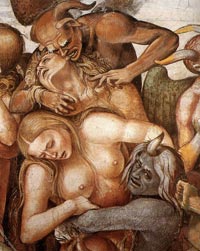

The Damned Consigned to Hell

|

|

Luca Signorelli, The Damned in Hell (with self-portrait of Luca Signorelli in the guise of a blue demon), 1499-1502, fresco cycle, Chapel of San Brizio, Orvieto Cathedral [6]

|

The account of the Apocalypse continues with three large scenes, the Resurrection of the Flesh, the Damned and the Elect, and two smaller ones on either side of the chapel's window, Paradise and Hell.

It is primarily in this section of the fresco cycle that Signorelli has given free rein to his inventive genius. An inventiveness that, as Berenson said, made him one of the greatest of modern illustrators, and thanks to which his art is still an extremely important part of our figurative heritage. Despite the rhetorical devices, the theatrical ruses and the occasional contrived details, despite the limitations in his draughtsmanship and use of colour recognized by all modern critics, there is no denying that never before in Italian art had figurative ideas of such unforgettable power been used. Viewed all together the huge frescoes in the Orvieto chapel give an impression of overcrowding and of confusion which is far from pleasing. We have to isolate the individual details in order to grasp the greatness of Signorelli the 'illustrator' and the 'inventor' and therefore justify Berenson's statement.[2]

Signorelli's fresco cycle in Orvieto is full of humor, grotesque inventions, erotic allusions and ribald jokes. There is no need to refer to the profane spirit of the Renaissance to explain this. On the contrary, these scenes fit in very well with the idea of the Cathedral as theatrum mundi, as the mirror image of the whole universe, and they are fully in the spirit of the religious plays of the time. Basically, neither Signorelli nor his patrons wanted to do without the enjoyment provided by story-telling, a typically Italian style based on humorous and imaginative details. But this in no way invalidates the dogmatic truth of the prophecies relating to the end of the world, which, especially in those turbulent years, really came across as a terrifying threat. It becomes quite understandable that Michelangelo would have been really interested in these Orvieto frescoes. But he in no way imitated Luca's work , (as Vasari would have us believe), for the spirituality and the moral content of the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel have absolutely nothing in common with the theatrical representation in Orvieto. Michelangelo perhaps found in Signorelli's frescoes a useful iconographical repertory, a catalogue of surprising and unusual inventions.

In any case the parts of the fresco cycle that would have attracted Michelangelo's curiosity most would certainly have been the scenes with devils and other imaginary figures, those scenes that were best suited to Signorelli's eccentric temperament, to his irony and macabre humour.

Luca Signorelli has portrayed himself as a devil, with just one horn in the middle of his forehead, he is embracing a beautiful blonde who is trying to break away from his fiery assault. Dürer’sSignorelli’s understanding of Hell is similar to Dürer’s: Hell is not some Biblical fantasy in a far-away place but in our heads. The veiled message of their art is that each of us, if we are to gain self-knowledge and higher consciousness, must face the torments of our own mind first . This understanding of Hell, and of the whole cycle in the Capella Nuovo in Orvieto, helps explain why one of the demons in the center of The Punishment is a portrait of Signorelli himself (at left). The demonic self-portrait is inside his own mind. Antonio Paolucci has argued that the selfportrait’s presence in Hell is a clear indication that the scene is more than just an illustration of a Biblical event.

|

|

Self-portrait of Signorelli as a demon

|

The Blessed Consigned to Paradise

|

|

Luca Signorelli, The Blessed, 1499-1502, fresco cycle, Chapel of San Brizio, Orvieto Cathedral [7]

|

|

|

|

The Paradise, or Coronation of the Chosen |

|

|

|

|

Paradise |

|

The south wall is pierced by three lancet windows, the central one over the altar, dividing the two principal frescoes of " Heaven " and " Hell." The former is a continuation of the last scene, and represents angels preceding the elect souls, and showing them the way to Heaven. In the sky, heavily embossed with gold like the last, float angels with musical instruments, one of whom, with face down-ward, blowing a pipe, is not so successfully foreshortened as is usual with Signorelli.

In the thickness of the small window which cuts into this fresco, are painted two coloured medallions, one of an angel vanquishing a devil, the other of S. Michael, with the balances, weighing soulsóboth by the master himself. Below are two series of small pictures in grisaille, with scenes from the "Purgatorio." The lowest is unfortunately hidden by the altar. All of them are by Signorelli himself, exceedingly good, and worthy of careful study, one being especially beautifulóthe top picture of the first series, in which Dante and Virgil stand before the Angel, with the gold-plumed Eagle in the foregroundóa most nobly conceived illustration to the ninth canto of the "Purgatorio."

|

|

|

The Damned Being Plunged into Hell

|

|

On the opposite side of the altar is the Judgment of Minos, and ,the driving of the lost souls to Hell under the superintendence of the two Archangels, who stand in the sky with drawn swords, sorrowfully watching the fulfilment of divine justice. Signorelli here has followed very closely the text of the " Inferno." In the foreground " Minos standeth horribly and gnasheth," condemning the miserable souls before him each to his different circle, his tail wound twice about his middle. Farther back, the Pistoiese, Vanno Fucci, with blasphemous gesture, yells out his challenge to God ; Charon plies his boat ; and in the background despairing souls follow a mocking demon who runs before them with a banner.

The scene of the Damned is constructed around the visionary, almost surrealistic, idea of these crowds of naked figures jostling for space along the banks of the Acheron.

In this representation, at the foot of two big mountains, along the shore of the Acheron, a devil with a white banner leads a group of damned. Other damned are in despair since they see Charon's boat getting near. Below there is Minos punishing a damned man. Above, two angels, one wearing a breast-plate and the other covered with veils, are watching the scene.

The two medallions on the sides of the window contain, one the Archangel Gabriel with the lily of the Annunciation, the other a very beautiful group of Raphael and Tobias, both by Signorelli himself.

|

|

|

|

Luca Signorelli, The Damned Being Plunged into Hell (detail), 1499-1502, fresco, Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto

|

| |

|

|

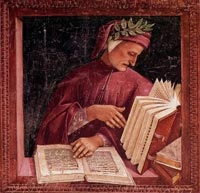

The lower parts of the walls are executed as decorative panels. In the center of each panel is a portrait of a poet or a philosopher – Dante, Virgil, Ovid, Horace, Lucian, Homer and Empedocles. Each portrait is surrounded by four tondos with the scenes from their works.

In his most celebrated work the Divine Comedy, Dante narrates a journey through Hell and Purgatory, guided by Virgil, and finally to Paradise, guided by Beatrice. The Divine Comedy gives an encyclopedic view of the highest culture and knowledge of the age all expressed in the most exquisite poetry. It was highly appreciated both by his contemporaries and following generations. Many artists took the subjects from the Divine Comedy for their paintings.

Signorelli also placed the portraits of Dante and his guide, Virgil, across the chapel from one another, thereby emphasizing that the Commedia is important to the cycle’s meaning. The other portrait is probably intended for Virgil, who, with upturned face and melodramatic expression, seems to seek for inspiration. This expression is exaggerated, but the painting is vigorous and strong.

Around, the medallions again represent subjects from the "Purgatorio," and are apparently by the same hand as the last, with the exception of the lower one, which seems to have some of Signorelli's own work in the nude figures.

Signorelli has separated the lower part of the wall by a painted frieze of delicate gold and ivory, and in the lower half executed a series of portraits, each surrounded by medallions in grisaille, containing small subject-pictures, the rest of the space being filled with an intricate pattern of grotesques. The south wall, in which are three small windows, has been unfortunately disfigured by a baroque seventeenth-century altar, whose projections hide a part of the frescoes. Opposite is the entrance, a magnificently-proportioned portal, with a rounded arch, most delicately decorated in colour. Every inch of the walls is covered, and for the most part by the work of Signorelli himself, the above-mentioned grotesques, the merely ornamental painting, and a few of the medallions alone being by his assistants.

One of the tondos in grisaille illustrates Canto 11 of Purgatorio, starting at line 73. It can now be seen as a reference to Signorelli’s own artistic tradition and future renown. It is the line in which the soul makes the famous comment about Giotto’s fame.

Signorelli depicted himself next to his predecessor Fra Angelico in the opening scene (see above right.)

|

|

Luca Signorelli, detail from Dante with Scenes from the Divine Comedy, San Brizio Chapel, Duomo, Orvieto

Dante and virgil entering the purgatory Dante and virgil entering the purgatory

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luca Signorelli, Storie degli ultimi giorni, ciclo di affreschi della Cappella di San Brizio, (c. 1499-1502), Orvieto, Duomo

|

|

Luca Signorelli, ciclo di affreschi della Cappella di San Brizio, (c. 1499-1502), Orvieto, Duomo

|

|

Luca Signorelli, I dannati all'inferno, 1499-1502, ciclo di affreschi, Cappella di San Brizio, Duomo di Orvieto

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

Opening hours of the San Brizio Chapel

November 1st – February 28th

weekdays: 10am - 12.45pm; 2.30 - 5.15pm

holidays: 2.30- 5.45pm

March and October

weekdays: 10am - 12.45pm; 2.30 - 6.15pm

holidays: 2.30- 5.45pm

1 April 1st – June 20th

weekdays: 10am - 12.45pm; 2.30 - 7.15pm

holidays: 2.30- 5.45pm

July 1st – September 30th

weekdays: 10am - 12.45pm; 2.30 - 7.15pm

holidays: 2.30 - 6.45pm

Tickets for the San Brizio Chapel are on sale in the Duomo or at the Azienda di Turismo.

For bookings contact Opera del Duomo di Orvieto, 26, Piazza del Duomo, 05018 Orvieto,

Tel. +39 0763.340336

Tel. +39 0763.343592

email: opsm@opsm.it

Jorie Graham, At Luca Signorelli’s Resurrection of the Body, from EROSION, Princeton University Press, 1983 | www.smith.edu

Jorie Graham was born in New York City in 1950, the daughter of a journalist and a sculptor. She was raised in Rome, Italy and educated in French schools. She studied philosophy at the Sorbonne in Paris before attending New York University as an undergraduate, where she studied filmmaking. Graham is the author of numerous collections of poetry, most recently Sea Change (Ecco, 2008), Never (2002), Swarm (2000), and The Dream of the Unified Field: Selected Poems 1974-1994, which won the 1996 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

Jonathan B. Riess, Luca Signorelli: The San Brizio Chapel, Orvieto, George Braziller, 1995

Sara Nair, Signorelli and Fra Angelico at Orvieto: Liturgy, Poetry, and a Vision of the End of Time, Ashgate Publishing, 2003

Antonio Paolucci, Luca Signorelli (Florence: Scala), 1990

Luca Signorelli - Orvieto (Originally Published 1908)

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Luca Signorelli, by Maud Cruttwell | www.gutenberg.org

Meltzoff, Stanley, Botticelli, Signorelli and Savonarola. "Theologia poetica" and painting from Boccaccio to Poliziano, Casa Editrice Leo S. Olschki, Firenze, 1987.

Ingrid D. Rowland, “When the Antichrist Came to Orvieto,” The New York Review of Books

Roderick Conway Morris, “The Soaring Legacy of Luca Signorelli,” NY Times

Dr. Shannon Pritchard, "Luca Signorelli, The Damned Cast into Hell," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed April 12, 2019, https://smarthistory.org/signorelli-the-damned-cast-into-hell/.

|

[0] The Damned consigned to Hell has a pronounced cruelty beyond even the medieval depictions of Hell in church sculpture. Here colourful shimmering demons, satyr goat-like hairy athletic bodies cheerfully strangle, throw the rejects to the Hell fire, all under a cloud supporting three armed angels who look thoroughly pleased about the cleaning up operation. In the Anti-Christ portion of the Last Judgment Signorelli inserted a portrait of Savonarola, the priest, being enflamed by Satan who is whispering in his ear.

Savonarola arrived in Florence in the summer of 1489. Now aged thirty-seven, he was a rather short, slender man, with deeply lined brow, hooked nose and prominent lips. What struck people most were his burning grey-green eyes under bushy dark eyebrows. His gestures in the pulpit were vehement, but the hands that made them were long, thin and translucent. … [Vincent Cronin, The Florentine Renaissance, Collins, U.K., 1967, p. 269]

[1] Luca Signorelli was born around 1450 in a bordering area of Umbria and Tuscany, in the town of Cortona. His career developed not only in the great capitals of art, such as Florence and Rome, but also in minor provincial centers in Umbria, Tuscany and Perugia.

He was reputedly a pupil of Piero della Francesca, then working in Arezzo, after which he worked with the Pollaiolo brothers in Florence but his own style did not mature until he went to Urbino. Here, among other works, he painted the Flagellation of Christ, now in Milan.

In 1481 he was among the artists chosen to execute the fresco cycle below the window area in the Sistine Chapel. Perhaps the most interesting is the enigmatic seated nude youth in Signorelli's Last Acts and Death of Moses, which is remarkably close to some of the Ignudi painted by Michelangelo on the ceiling of the chapel a quarter of a century later. In Rome Signorelli worked in close contact with Perugino, whose style influenced the Signorelli one, which softened noticeably. This can be seen in the frescos he painted for the sacristy of the Loreto Santuary and his St. Onofrio Altarpiece for Perugia Cathedral (1484).

After Rome Signorelli moved to Florence where he became a painter in Medici circles. During this period he produced the panels now in the Ufizzi including a tondo of the Madonna and Child.

Following Lorenzo's death in 1492, the painter chose to leave Florence. First he worked, 1496-98, on a fresco cycle in the abbey cloisters at Monteoliveto Maggiore. The subject of those frescos was the Life of St. Benedict. After that work he was commissioned to finish the decoration of the San Brizio Chapel in the Orvieto Cathedral.

|

|

Luca Signorelli, Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist (detail, portrait of Savonarola) |

[2] PORTRAITS OF SIGNORELLI AND FRA ANGELICO

Fifty-two years before, in 1447, Fra Angelico had spent three months and a half in this Cathedral of Orvieto, painting the spandrels in the roof of the Cappella Nuova, as it was then called.[62] He had time to complete only two frescoes, being either recalled to Rome by Nicholas V., or to the convent of S. Domenico, near Fiesole (of which, in 1450, he was made Prior). These two works are among the best and strongest of his paintings. In the principal space, that over the altar, he painted Christ in glory, surrounded by a mandorla, with angels on either side; and in the spandrel on the right, a group of sixteen prophets, seated pyramidally against a blaze of gold background. It is probable that he had thought out the general scheme of the frescoes, and that Signorelli only carried out his intention in working the paintings into one great whole—Christ in Heaven, surrounded by Angels, Apostles, Martyrs, Virgins, Patriarchs and Fathers of the Church, witnessing from on high the execution of divine justice below. However that may be, it is[Pg 66] certain that Signorelli, in his painting of the roof, kept most scrupulously to the older master's arrangement, and in one of the spandrels actually seems to have worked over his design.

After the withdrawal of Fra Angelico, the chapel remained untouched for more than fifty years. In 1449 his pupil, Benozzo Gozzoli, who had probably been his assistant in the painting, demanded permission to continue the work; but the authorities were not content to grant it, and it was only in 1499, after some futile negotiations with Perugino, who appears to have refused the commission, that they finally resolved to place the decoration in the hands of Signorelli. Perhaps decided to this step by the success of the Monte Oliveto frescoes, they were yet so cautious and so determined to have only the very best work in their chapel, that at first they only entrusted to him the painting of the vaulting, already begun. They were wise to be careful in their choice, for they were probably conscious of the extreme beauty of their cathedral, and, in particular, of the exquisite architecture of this chapel. Orvieto Cathedral is one of the finest and most impressive of the Italian churches, and from its foundation in 1290, the authorities had been notoriously lavish in their expenditure for its building, and fastidious in their choice of architects, sculptors, and painters.[63] From the point of view merely of decoration, they could have given the work to no better artist than Signorelli, and the first impression, on passing into the chapel from the austere and[Pg 67] spacious nave, is of the harmonious plan, both of colour and design, with which the original beauty of the architecture has been enhanced, and its graceful characteristics accentuated.

The roof is of very perfect shape, and the spaces well adapted for painting. It is divided in the middle by an arch, thus having two complete vaultings, each with four spandrels. The walls are high and spacious, also divided in two parts, in each of which, on either side, is a large fresco. Signorelli has separated the lower part of the wall by a painted frieze of delicate gold and ivory, and in the lower half executed a series of portraits, each surrounded by medallions in grisaille, containing small subject-pictures, the rest of the space being filled with an intricate pattern of grotesques. The south wall, in which are three small windows, has been unfortunately disfigured by a baroque seventeenth-century altar, whose projections hide a part of the frescoes. Opposite is the entrance, a magnificently-proportioned portal, with a rounded arch, most delicately decorated in colour. Every inch of the walls is covered, and for the most part by the work of Signorelli himself, the above-mentioned grotesques, the merely ornamental painting, and a few of the medallions alone being by his assistants.

In describing the frescoes I intend to begin with those of the vaulting, and then to work gradually round the walls from the left of the entrance, where the first of the series of larger paintings begins with "The Preaching and Fall of Antichrist."

In the spandrel opposite the Christ of Fra Angelico, Signorelli has painted eight angels holding the symbols of the Passion, while two others, not unlike the great Archangels of the "Resurrection," blow trumpets to announce the impending Judgment.

Left of the altar, opposite Fra Angelico's "Prophets," and arranged in exactly the same pyramidal form, is a magnificent group, representing the "Apostles," the Virgin being seated on the lowest tier with S. Peter and S. Paul. Very noble, impressive figures, powerfully and solidly painted, with broadly-draped, heavy-folded robes, they sit like rocks upon clouds as solid as hills.

These, with the two frescoes of Fra Angelico, complete the paintings of the first vaulting.

Those on the other side of the arch are executed entirely by Signorelli, and, with the exception of one, from his own designs. This one is the weakest of his roof-paintings in execution, and the composition and actual drawing of the central figures, are the work of Fra Angelico. It represents the "Choir of Martyrs," a group of seven figures. In the centre are seated three Deacons in full canonicals, with Bishops on either side, and below two Saints in plain robes. These last have all Signorelli's characteristics of drawing, and sit with wide-spread knees and broadly-painted draperies, a striking contrast to the weak attitudes and niggling robes of the central group. Signorelli has indeed hardly altered the childish chubby features of the Deacon in the middle, nor the benevolent vacuity of the two Bishops, so different to his own austere types.

Opposite to this, over the portal, is a group of eight "Virgins," broadly and vigorously treated, in Signorelli's[Pg 69] boldest manner. To the right is another of the pyramidal groups, fifteen "Doctors of the Church," some of whom are represented disputing and discussing points of theology.

The last of the roof-paintings is a powerful group of "Patriarchs," ranking, with that of the "Apostles," among the most impressive of the frescoes. Here appear many of his well-known types of face; the melancholy features of Pan are repeated in the turbaned youth in the top row, intended perhaps to be Solomon; the Christ of the Uffizi "Holy Family" is in the second tier to the left; the powerful Zacharias from the Berlin Tondo in the lowest.

Luzi, in his minute description of the paintings,[64] has bestowed names on all these figures, without much advantage, since they are for the most part doubtful. Few of them bear symbols, but the different groups are sufficiently described in large letters, by the painters themselves—GLORIOSVS APOSTOLORVM CHOIR—MARTIRVM CANDIDATVS EXERCITVS—etc. etc.

The figures, with the exception of those by Fra Angelico, and the design for the "Martyrs," are entirely the work of Signorelli himself. The decorations between the spaces seem to be in part by the assistant of Fra Angelico—perhaps Benozzo Gozzoli. In the first border heads are painted, in lozenges, at regular intervals, a few of which are in the older master's style, while many show the manner of Signorelli. The rounded projecting rib is painted with foliage of cypress-green, with here and there rich red and golden flowers gleaming out, and on either side a border of[Pg 70] conventionalised water-lilies. It is difficult to say which of the masters designed this exceedingly beautiful decoration, but it is most effective, and well-calculated to accentuate the life of the fine curves in the vaulting.

by Maud Cruttwell, The Project Gutenberg eBook of Luca Signorelli, p 70 | www.gutenberg.org

|

|

Luca Signorellli, self portrait (on the left) with Fra Angelico in the San Brizio Chapel, Orvieto Luca Signorellli, self portrait (on the left) with Fra Angelico in the San Brizio Chapel, Orvieto |

[3] What the Nude is and whence its supereminence in the figure arts, I have discussed elsewhere. I must limit myself here to the statement that the nude human figure is the only object which in perfection conveys to us values of touch and particularly of movement. Hence the painting of the Nude is the supreme endeavor of the very greatest artists; and, when successfully treated, the most life communicating and life-enhancing theme in existence. The first modern master to appreciate this truth in its utmost range, and to act upon it, was Michelangelo, but in Signorelli he had not only a precursor but almost a rival. Luca, indeed, falls behind only in his dimmer perception of the import of the Nude and in his mastery over it. For his entire treatment is drier, his feeling for texture and tissue of surface much weaker, and the female form revealed itself to him but reluctantly. Signorelli's Nude, therefore, does not attain to the soaring beauty of Michelangelo's; but it has virtues of its own a certain gigantic robustness and suggestions of primeval energy.

The reason why, perhaps, he failed somewhat in his appreciation of the Nude may be, not that 'the time was not ripe for him', as is often said, but rather that he was a Central Italian which is almost as much as to say an Illustrator. Preoccupied with the purpose of conveying ideas and feelings by means of his own visual images, he could not devote his complete genius to the more essential problems of art. Michelangelo also was an Illustrator alas! but he, at least, where he could not perfectly weld Art and Illustration, sacrificed Illustration to Art.

But a truce to his faults! What though his nudes are not perfect; what though as in candour must be said his colour is not always as it should be, a glamour upon things, and his composition is at times crowded and confused? Luca Signorelli none the less remains one of the grandest - mark you, I do not say pleasantest - Illustrators of modern times. His vision of the world may seem austere, but it already is ours. His sense of form is our sense of form; his images are our images. Hence he was the first to illustrate our own house of life. Compare his designs for Dante (frescoed under his Heaven and Hell at Orvieto) with even Botticelli's, and you will see to what an extent the great Florentine artist still visualizes as an alien from out of the Middle Ages, while Signorelli estranges us, if indeed at all, not by his quaintness but by his grand austerity.

It is as a great Illustrator first, and then as a great artist that we must appreciate Signorelli. And now let us look at a few of his works works which reveal his mastery over the nude and action, his depth and refinement of emotion, the splendour of his conceptions. How we are made to feel the murky bewilderment of the risen dead, the glad, sweet joy of the blessed, the forces overwhelming the damned! It would not have been possible to communicate such feelings but for the Nude, which possesses to the highest degree the power to make us feel, all over our own bodies, its own state. In these frescoes at Orvieto how complete a match for the 'Dies Irae' are the skies with their overshadowing trains of horror, and the trumpet blasts of the angels! What high solemnity in his Volterra 'Annunciation' - the flaming sunset sky, the sacred shyness of the Virgin, the awful look of Gabriel! At Cortona, in an 'Entombment', you see Christ upheld by a great angel who has just alighted from a blessed sphere, its majesty still on his face, its dew on his wings. Look at Signorelli's music making angels in a cupola at Loreto. Almost they are French Gothic in their witchery, and they listen to their own playing as if to charm out the most secret spirit of their instruments. And you can see what a sense Signorelli had for refined beauty, if, when sated with Guido's 'Aurora', you will rest your eyes on a Madonna by him in the same pavilion of the Rospigliosi Palace.

The Nude for its own sake, for its distinctly tonic value, was used by Signorelli in one of the few most fascinating works of art in our heritage I mean his 'Pan' at Berlin. The goat footed Pan, with the majestic pathos of nature in hit, aspect, sits in the hushed solemnity of the sunset, the tender crescent moon crowning his locks. Primevally grand nude figures stand about him, while young Olympos is piping, and another youth lies at his feet playing on a reed. They are holding solemn discourse, and their theme is 'The Poetry of Earth is never Dead'. The sunset has begotten them upon the dew of the earth, and they are whispering the secrets of the Great Mother.

And now, just a glance at one or two of Luca's triumphs in movement. They are to be found chiefly in his predelle, executed in his hoary old age, where, with a freedom of touch at times suggesting Daumier, he gives masses in movement, conjoined, and rippling like chain mail. Perhaps the very best are certain bronzed predelle at Umbertide, a village situate upon the Tiber's bank; but more at hand is one in the Uffizi, painted in earlier years, an 'Annunciation', wherein the Angel runs so swiftly that he drinks the air before him.

- From Bernard Berenson, "Italian Painters of the Renaissance"

[4] Source: Rose Marie San Juan, The Illustrious Poets in Signorelli's Frescoes for the Cappella Nuova of Orvieto Cathedral, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 52, (1989), pp. 71-84, published by: The Warburg Institute | www.jstor.org

[5] Photo by Slices of Light, published under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) license.

[6] Photo by Rafael Edwards, published under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) license.

[7] Photo byRichard Mortel, published under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) license.

|

|

Orvieto, Duomo

|

Orvieto is one of the principal sights of the region of Umbria, Italy. Its situation is marvelous - perched high above tufa cliffs - showing traces of every phase of history for the past three thousand years, culminating in its magnificent cathedral. Tourists should on no account miss Orvieto if they are visiting Umbria or southern Tuscany. The tufa butte on which Orvieto is located is itself riddled with tunnels and wells dating from Etruscan times to only a couple of hundred years ago. The most spectacular of these subterranean burrowings is the Pozzo di San Patrizio, a deep well with a double spiral stair leading to the water source at its base. It dates from 1537 and is 62 m deep. If you're in need of exercise, it's possible to descend and return. Try carrying up a couple of buckets of water - it'll bring the life of earlier times vividly before you.

The cathedral of Orvieto is one of the most beautiful churches in Umbria, indeed in all of Italy. It was begun in 1285 and is Gothic in style, with three naves. Its tripartite façade was conceived by Lorenzo Maitani and is decorated in its lower portion with scenes from the Old and New Testaments, and with mosaics and statues of the Blessed Virgin, the Prophets and the Apostles in its upper part. The walls in the interior are constructed of layers of Travertine marble and of basalt. The choir was frescoed with illustrations of the life of the Blessed Virgin by Ugolino di Prete Ilario, Peter di Puccio and Anthony of Viterbo. The chapel on the right, called Our Lady of San Brizio, was painted by the Fra Angelico of Fiesole ("Christ Glorified", "Last Judgment", and "The Prophets", carried out in 1447) and by Luca Signorelli ("Fall of Antichrist", "Resurrection of the Dead", "Damned and Blessed", etc.). Michelangelo took inspiration from these paintings for his "Last Judgment" in the Sistine Chapel. The "Burial of Jesus" is also by Signorelli, and there are several sculptures by Scalza (1572), among them the group of the Pietà, chiselled from a single block of marble. The chapel on the opposite side, called "of the Corporal", contains the large reliquary in which is preserved the corporal of the miracle of Bolsena. This receptacle was made by order of Bishop Bertrand dei Monaldeschi, by the Siennese Ugolino di Mæstro Vieri (1337). It is made of silver, adorned with enamels that represent the Passion of Jesus and the miracle. The frescoes of the walls, by Ugolino (1357-64), also represent the miracle.

Cortona is a small but fascinating city in the province of Arezzo, Tuscany, central Italy, situated on a commanding hill, and overlooking Lake Trasimeno. Its cyclopean walls reveal its Etruscan origins. It was one of the twelve cities of Etruria and in its vicinity many ruins and Etruscan tombs may be seen. Cortona sided against Rome until 310 B.C. when Fabius Rullianus defeated the Etruscans and took Perugia. Perugia, with other cities, including Cortona, then made peace with Rome. Later Cortona was destroyed by the Lombards but was soon rebuilt. In the 14 C, it was governed by the Casali and afterwards became part of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.

Many famous men were born or lived in Cortona, among them Brother Elias (Elia Coppi), the famous companion of St. Francis of Assisi, and later Vicar-General of the Franciscan Order; Cardinals Egidio Boni and Silvio Passerini; the painter Luca Signorelli; the architect and painter Pietro Berrettini (Pietro da Cortona). St. Margaret of Cortona (1248-97) was born at Laviano (Alviano) in the Diocese of Chiusi, and became the mistress of a nobleman of the vicinity. On discovering his body after he had met a violent death, she repented and, after a public penance, retired to Cortona, where she took the habit of a Tertiary of St. Francis and devoted her life to works of penance and charity. Leo X permitted her veneration at Cortona, and Urban VIII extended the privilege to the Franciscan Order. Benedict XIII canonised her in 1728. Her body rests in a beautiful sarcophagus in the church dedicated to her at Cortona.

It is not known whether Cortona was an episcopal see previous to its destruction by the Lombards. From that time until 1325 it belonged to the Diocese of Arezzo. In that year, at the request of Guglielmo Casali, John XXII raised Cortona to episcopal rank, as a reward for the fidelity of its Guelph populace, Arezzo remaining Ghibelline. The first bishop was Rainerio Ubertini. Other bishops were Luca Grazio, who was a distinguished member of the Council of Florence (1438); Matteo Concini (1560) and Gerolamo Gaddi (1562) were present at the Council of Trent. The cathedral and the other churches of Cortona possess numerous works of art, especially paintings of the school of Luca Signorelli and of Fra Angelico.

The Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore is located 36 km south of Siena in the characteristic "badlands" landscape of the Crete Senesi. The Olivetan community traces its foundation to 1313 and Giovanni Tolomei - who took the religious name of Bernardo - along with two of his friends, from the noble families of Sienna, Patrizio Patrizi and Ambrogio Piccolomini. The Abbey is situated 273 m above sea level at Chiusura, not far from Asciano in the province of Sienna, surrounded by the thick forest that overlooks the Crete Senesi countryside below.

The correct name for the monks of the Abbey of Monte Oliveto, who are part of a number of congregations that make up the Benedictine order, is in fact Monaci Benedettini di Santa Maria di Monte Oliveto. Their particular devotion to the Virgin Mary is visible also in their habit, which is white to symbolise purity.

The approval for the building of the monastery came with the "Charta fundationis" by Guido Tarlati, bishop of Arezzo (26 March 1319), and the monastery took the name of Monte Oliveto «Maggiore» (Major) so as to distinguish it from successive foundations (Florence, San Gimignano, Naples, etc.). Construction of the monastery began in 1393 and was completed in 1526, although the buildings were further modified during the Renaissance and the Baroque periods.

An imposing square tower with a drawbridge that was part of the original defences erected to protect the entire complex stands at the entrance to the Abbey. The courtyard of the abbey opens onto a broad avenue of cypresses. To the left is the botanical garden that supplied medicinal plants for the monks. A little further on is the fish pond designed in 1553 by Pelori and used by the monks to provide fish at those times of year during which the Benedictine rule forbade the consumption of meat.

The cypress avenue leads to the impressively austere, late-gothic church of the abbey, built between 1399 and 1417 by order of the Abbot Ippolito di Giacomo da Milano. The single nave interior has a cross plan. The fine carved wooden lector is by Raffaele da Brescia and the inlaid wooden choir stalls are by Fra’ Giovanni da Verona. The transept leads to the Chapel of the Sacrament, whose altar is adorned by an early 14 C wooden Crucifix. In 1772 the church was redecorated in the late-Baroque style by Giovanni Antinori.

The abbey has three 15 C cloisters, of which the most magnificent is the rectangular Chiostro Grande, constructed between 1426 and 1443. It is made up of two passages, one above the other, supported by columns. The portico is decorated with a fresco cycle by Luca Signorelli depicting the life of St Benedict, who began work on its 36 large scenes in 1497. The cycle was finished in 1508 by Sodoma. The Chiostro Centrale is composed of a portico that rests on polygonal columns that lead to the magnificent Refectory, decorated with frescoes by Fra’ Paolo Novelli.

The abbey’s large Library comprises more than 40,000 volumes, pamphlets and parchments that have been carefully restored by the monks. The Library leads to the Pharmacy, which contains an important collection of 18 C spice vases. The abbey still produces honey and distilled herbal spirits made according to various ancient recipes.

Art in Tuscany | Sodoma (originally Giovanni Antonio Bazzi)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sansepolcro |

One of Tuscany's best kept secrets is the beautiful valley sheltering this recently renovated 18th century farm house, a podere retaining all the charm and delight of its past combined with updated comfort. Podere Santa Pia, a former cloister with an authentic character, is located in the heart of the Valle d'Ombrone, and one can easily reach some of the most beautiful attractions of Tuscany, such as Montalcino, Pienza, Montepulciano and San Quirico d'Orcia, famous for their artistic heritage, wine, olive oil production and gastronomic traditions. It is the ideal place to pass a very relaxing holiday in contemplation of nature, with the advantage of tasting the most typical dishes of Tuscan cuisine and its best wines.

The hidden secrets of southern Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia | Artist and writer's residency

|

| |

|

|

|

|

. |

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, December |

|

View from Podere Santa Pia

on the coast and Corsica |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luca Signorellli, self portrait (on the left) with Fra Angelico in the San Brizio Chapel, Orvieto

Luca Signorellli, self portrait (on the left) with Fra Angelico in the San Brizio Chapel, Orvieto