| |

|

Giovanni di Paolo di Grazia was one of the most important Italian painters of the 15th-century Sienese school. He is chiefly notable for carrying the brilliantly colourful vision of Sienese 14th-century paintings on into the Renaissance. His early works show the influence of previous Sienese masters, his landscapes and his figures still reverberate with echoes of Duccio's work, but his later style grew steadily more individualized, characterized by vigorous, harsh colors and elongated forms. His art most beautifully reflects the 15th-century artistic conservatism of a commercially declining city.

Many of his works have an unusual dreamlike atmosphere, while his last works - particularly Last Judgment, Heaven, and Hell (1465?) and Assumption of the Virgin (1475), both at Pinacoteca, Siena - are grotesque treatments of their lofty subjects. Giovanni's reputation declined after his death but was revived in the 20th century.

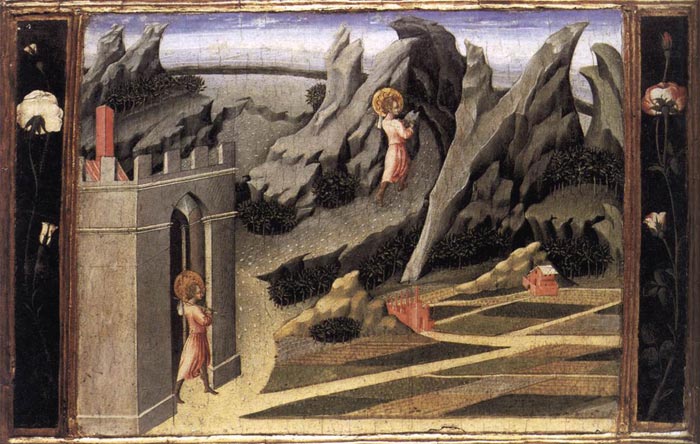

Between 1445 and 1460, Giovanni di Paolo painted a series of panels depicting the life of Saint John the Baptist, the kinsman and prophet of Christ. The panels from the series are scattered in European and American collections; they may originally have formed the doors of a shrine housing a relic of the saint.

The narrative sequence of "Life of Saint John the Baptist"" originally comprised twelve panels. In addition to the six at the Art Institute in Chicago, an "Annunciation to Zacharias" is preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), a "Baptism of Christ" in the Norton Simon Museum (Pasadena), a "Birth of Saint John the Baptist" and a "Saint John the Baptist Accusing Herod" at the Westfälisccches Landesmuseum (Münster, Germany), and a fragment of "Saint John the Baptist and the Pharisees" in the Louvre (Paris); the twelfth panel, still missing, probably represented the "Baptism of the multitude".

In the first panel (on the right), the young Baptist enters the wilderness to live as a hermit; later he foretells Christ's role as redeemer, is imprisoned, and is finally martyred at the request of Salome, the step-daughter of King Herod.

|

|

|

| |

|

Saint John the Baptist Entering the Wilderness, The Art Institute of Chicago

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Head of Saint John the Baptist

Brought before Herod, 1455/60 [4] |

|

Saint John the Baptist in Prison Visited by Two Disciples [4]

|

|

The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist [4] |

|

| Giovanni di Paolo, The Head of Saint John the Baptist Brought before Herod, (detail) |

|

|

|

| |

|

[1] 'Catherine Benincasa was born in Siena in about 1347, died in 1380, and was canonized in 1461. She was a member of the Dominican order, a mystic, and minister to the poor and plague-stricken. A biography of Saint Catherine was written by her confessor, Raymond of Capua. In this scene, Catherine is shown elevated in rapture against a background of several churches. She holds out her heart to Christ, who appears above her, his hand raised in blessing. The Museum owns four additional panels from the series: two more in the Department of European Paintings, "The Miraculous Communion of Saint Catherine of Siena" (32.100.95) and "The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena" (1997.117.2), and two in the Robert Lehman Collection, "Saint Catherine of Siena Beseeching Christ to Resuscitate Her Mother" (1975.1.33) and "Saint Catherine of Siena Receiving the Stigmata" (1975.1.34).

The other five panels are: "Saint Catherine Invested with the Dominican Habit" and "Saint Catherine and the Beggar" (both Cleveland Museum of Art), "Saint Catherine Dictating Her Dialogues to Raymond of Capua" (Detroit Institute of Arts), "Saint Catherine before a Pope" (Thyssen-Bornemisza Foundation), and "Death of Saint Catherine" (private collection, ex-Minneapolis Institute of Arts).

This series is usually associated with an altarpiece commissioned from Giovanni di Paolo by the guild of the Pizzicaiuoli (purveyors of dry goods) in 1447 for the church of the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena. The central panel of the altarpiece is a "Purification of the Virgin" ["Presentation of Christ in the Temple"] now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena. Other panels connected with the altarpiece include a "Crucifixion" (Rijksmuseum Het Catharijneconvent, Utrecht, on deposit at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), and pilaster figures representing Saint Galganus and the Blessed Peter of Siena(?) (both Aartbischoppilijk Museum, Utrecht), and the Blessed Andrea Gallerani and the Blessed Ambrogio Sansedoni (both Robert Lehman Collection, MMA).

Scholars disagree on the relationship between the Pizzicaiuoli altarpiece and the series of ten panels depicting scenes from the life of Saint Catherine. Their arguments fall into three broad categories: 1) the panels were part of the original commission for the altarpiece and were thus painted between 1447 and 1449 [see Refs. Brandi 1941, Coor-Achenbach 1959, and Os 1971]; 2) they were added to the altarpiece after Catherine's canonization in 1461 [see Refs. Pope-Hennessy 1947 and Gore 1965]; 3) they are not related to the Pizzicaiuoli altarpiece at all, but originally surrounded an image of Saint Catherine.'

The Metropolitan Museum of Art | European Paintings | Giovanni di Paolo (Giovanni di Paolo di Grazia), Saint Catherine of Siena Exchanging Her Heart with Christ

John Pope-Hennessy compares the panels stylistically with Giovanni di Paolo's Pienza altarpiece of 1463, and also calls it unlikely that a cycle of scenes from Catherine's life would be included in a major altarpiece before her canonization in 1461; therefore thinks that the panels were either a later addition to the Pizzicaiuoli altarpiece or were made for a different work.

John Pope-Hennessy (assisted by Laurence B. Kanter in "Italian Paintings." The Robert Lehman Collection. 1, New York, 1987, pp. 128, 130–32

[2] Masterpieces in Miniature: Italian Manuscript Illumination from the J. Paul Getty Museum | www.nga.gov

[3] The term has also been extended to designate painted covers and small panels connected with other Sienese civic offices and institutions, such as the tax office (Gabella), the hospital of S Maria della Scala, the Opera del Duomo and various lay confraternities. Most biccherne, however, are from the office of the Biccherna itself.

The first wooden boards are simple and have no intention of being masterpieces. Subsequently, however, the paintings become more elaborate and rich and are commissioned to famous authors as Giovanni di Paolo, Sano di Pietro, Lorenzo di Pietro called il Vecchietta.

Museum of the Biccherna Tablets in Siena. In Palazzo Piccolomini, typical style of Florentine Renaissance, this museum holds the ancient tablets of the state ledgers and a collection of ancient manuscripts and books.

Archivio di Stato di Siena | Collezione delle Tavolette di Biccherna e Mostra documentaria | www.archiviostato.si.it (it)

The Museum is located in Via Banchi di Sopra # 52 and it is open from Monday to Saturday at 9.30 - 10.30 and 11.30

Free entrance.

|

Art in Tuscany | Sienese Biccherna Covers | Biccherne Senesi

H. W. van Os, Giovanni di Paolo's Pizzicaiuolo Altarpiece, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Sep., 1971), pp. 289-302

|

Podere Santa Pia is an old 'podere' or farmhouse that dates back to the 19th century, now lovingly restored with many of the original details preserved. With its original kitchen and the wood burning pizza oven, Podere Santa Pia offers an upbeat atmosphere. Here you can sample all the dishes of the typical cuisine of the Maremma.

Secret treasures in southern Tuscany | Podere Santa Pia

|

|

|

. |

|

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Podere Santa Pia, garden view, April |

|

|

|

Located in the heart of the Maremma, in southern Tuscany, Podere Santa Pia sits alone on a spectacular, private and tranquil hillside setting with expansive open views up to the sea and Montecristo.

|

Siena in the Middle Ages

Siena reached the height of its splendour in the Middle Ages, when in 1147 it became an independent comune after a century of rule under the bishop. After gaining its independence, the city adopted an expansionistic policy, considerably increasing its domains. But the development and riches brought by trade also accompanied social conflict, which soon developed into a bloody struggle for supremacy between Guelphs and Ghibellines, the two opposing factions that supported respectively the Church and the Empire. Due to its Ghibelline status, Siena went to war against neighbouring Florence, which supported the Pope. Its troops gained a formidable victory against the Florentines at the Battle of Monteperti, on September 4th 1260. Only nine years later, however, Siena was in turn defeated by Florence and the city passed into Guelph hands, heralding a new government and a long period of prosperity.

Siena reached its golden age of architecture during the 14th century, when the city was able to erect many of the most important buildings that survive to this day. These include the Campo, the Palazzo Pubblico (then known as Palazzo dei Signori in reference to the city’s ‘Nine’ governors) the Duomo and the Torre del Mangia. This was also the period in which Senese art flourished, with masterpieces such as Duccio’s Maestà. At this time the city invested enormously in costly projects such as the building of the fortified village of Paganico or the port at Talamone.

But Siena was also known for its lavish feasts and tournaments, such as the Gioco dell’Elmora, in which young men fought one another with clubs and stones. This game was supplanted in 1291 with the Gioco delle Pugna, in which the contenders fought with their hands covered by a wicker structure, or other games such as the Pallonata or the Bufalata. Piazza del Campo was frequently used for a variety of horse races, which developed over the centuries into the city’s best known event, the Palio.

In emulation of ancient Rome, Siena wished to underline its independence. But the great Plague of 1348 decimated the city’s population, bringing decadence and financial collapse. In the fifty years that followed, the city underwent considerable political upheaval, famine and rebellion, which culminated in the end of the government of the ‘Nine’ and loss of independence when in 1390 the city was annexed to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.

Despite losing their independence, the people of Siena retained their proverbial courage and cunning. St Catherine of Siena, who during her lifetime was called Caterina Benincasa, died in 1380 after playing an instrumental role in bringing back the Papacy to Rome from its exile in Avignon, thereby proving that the city had not altogether lost its political influence.

Siena in the Renaissance

Just as it reached its greatest political, financial, social and artistic splendour during the 14th century, during the following century the city of Siena appeared destined to live out its final twilight.

With the end of the government of the Nine, Siena entered a period of political instability. In 1403, the ruling Monte dei Dodici was accused of trying to seize definitive power and deposed. There followed a time during which the city was ruled by the Monti Popolari, known as the “Tripartito”, which remained in power until 1480.

During the Renaissance, Siena was a relatively small town of about 15,000 inhabitants. The Senese community as a whole was heavily involved in the duties of public office and each individual had a strong sense of personal duty towards the public administration. This explains why many of the city’s great art treasures were commissioned by the city and not by noble families, whose members were far too busy carrying out their functions as Podestà. The Opera del Duomo at the time grew into a kind of artistic and architectural commission that administered the Palazzo della Mercanzia and the Cappella di Piazza.

Although in many ways a good thing, the great sense of civic duty that characterised the Senese meant that a good deal of animosity would spring up between any number of people and factions on any number of issues concerning the public administration. A remarkable man named Pandolfo Petrucci was thus able to take advantage of such a chaotic situation, gradually developing his influence to such an extent that he became the ruler of Siena in all but name. An able political manipulator, Petrucci effectively governed the city for about twenty years, from 1400, without actually doing away with its traditional government bodies. Under Petrucci’s rule the architecture of Siena developed considerably. Petrucci erected his own opulent palazzo, naming it Palazzo del Magnifico, but his untimely death when still a young man plunged the city into a new period of political upheaval.

Weakened by internal strife, Siena became an easy prey in the territorial designs of the great European powers such as France and Spain. In 1553 Florence allied itself with the Holy Roman Empire and invaded. Siena, which at the time numbered less than 10,000 inhabitants, fell the following year, passing under the direct rule of Cosimo De’ Medici in 1557, who celebrated by ceremonially entering the city and watching a play in the Palazzo Palazzo Pubblico. From this moment onwards, Siena followed the fortunes of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and its ruling Medici family.

On a constitutional level, Siena was not annexed to the Florentine state, retaining its Republican Statute (1544-45) as a newly formed state until the second half of the 16th century with the reforms introduced by Peter Leopold.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Siena, Palazzo Publico |

|

Siena, Duomo

|

|

Val d'Orcia |

[4] This article uses material from the Wikipedia article Giovanni di Paolo.

Images: Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giovanni di Paolo.

|

|

|

|