|

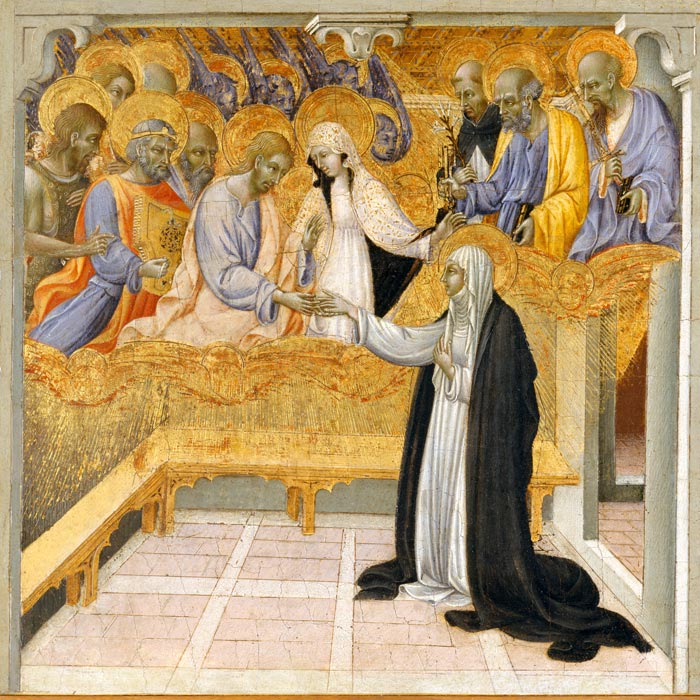

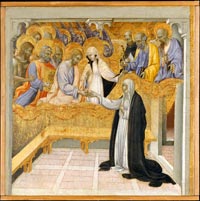

Giovanni di Paolo, The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena (detail), circa 1460, or earlier, Metropolitan Museum, New York |

Giovanni di Paolo | The life of St. Catherine of Siena |

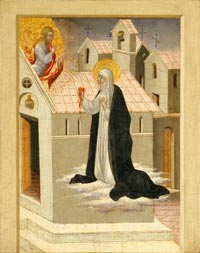

| Saint Catherine who was canonised in 1461 by Pope Pius II, was born in Siena around 1347. Despite the opposition of her family, who wished her to marry and form a family, she entered the Dominican Order as a Tertiary The saint, who led a life of privation and penitence, dedicated her existence to care of the sick. Among the most frequently depicted episodes in her life are her mystic marriage, her ecstasy and the miracle that took place before the tomb of Saint Agnes for whom Catherine expressed profound devotion. Saint Catherine was a member of the Dominican order, a mystic, and minister to the poor and plague-stricken. A biography of Saint Catherine was written by her confessor, Raymond of Capua.[1] |

||

|

||

|

||

Giovanni di Paolo, The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena, circa 1460, or earlier, Metropolitan Museum, New York |

||

The popular tales about Catherine that derived from Raymond's Legenda are shown here in several panels created by Giovanni di Paolo at the time of her canonization in 1460.[2] This panel is from the predella of an altarpiece that was in the church of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena. According to the abbot Giovanni Girolamo Carli this ensemble was dismantled and cut up into panels of different sizes for display in different parts of the church in the second half of the 18th century. The eleven panels that comprised the predella have been identified in various museums and private collections. They are: Saint Catherine taking the Habit of the Dominican Order and Saint Catherine and the Beggar in the Cleveland Museum of Art; The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Saint Catherine exchanging her Heart with that of Christ and The Death of Saint Catherine in various private collections; Saint Catherine receiving the Stigmata, Saint Catherine pleading to Christ to revive her Mother and The Miraculous Communion of Saint Catherine in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Saint Catherine dictating her Dialogues in the Detroit Institute of Art; and The Crucifixion which is the central scene in the predella, in the Rijksmuseum in Utrecht.

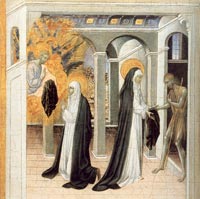

These three panels are from a series of ten scenes that originally formed the predella of an altarpiece painted by Giovanni di Paolo for the hospital church of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena. This was among the artist's most important commissions, and the predella, painted soon after Saint Catherine's canonization in 1460, was the first extensive pictorial cycle of her life. A mystic as well as minister to the poor and plague-stricken, Saint Catherine was one of the outstanding figures of the fourteenth century. A biography was written by her confessor, Raymond of Capua, and this work provided the source for Giovanni di Paolo's scenes. In the first scene, The Miraculous Communion of Saint Catherine of Siena, Catherine miraculously receives communion from Christ while her confessor, officiating at another chapel in the church, raises his hand in astonishment at the consecrated wafer, from which a piece has disappeared. In the second, Catherine is mystically united with Christ. Christ's mother presides over the event, and music is provided by the Israelite King David. In the third, Catherine is shown elevated in rapture, holding her heart, which leapt out of her body to be united with Christ's. Among the most notable features of these pictures is the way space is manipulated to underscore the mystical nature of the stories. Two further scenes are in the Metropolitan (Robert Lehman Collection). |

The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena, circa 1460, or earlier, Metropolitan Museum, New York The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena, circa 1460, or earlier, Metropolitan Museum, New York  Saint Catherine of Siena Dictating Her Dialogues, c. 1447/1449, Detroit Institute of Arts

The Miraculous Communion of Saint Catherine of Siena

|

|

|

||

Giovanni di Paolo, Crucifixion, 1461, tempera and gold on panel, 29.8 x 62.7 cm, Utrecht, Rijksmuseum Het Catharijneconvent |

||

| Saint Catherine (1347-1380) was the daughter of a prosperous Sienese cloth dyer. At the age of six, she saw a vision of Christ and thereafter dedicated herself to chastity, penance, and good works. She became extremely popular in Siena when she selflessly cared for the sick and dying victims of the bubonic plague, known as the Black Death. These two panels were part of the predella (or pedestal) of a large altarpiece painted for the Hospital Church of Siena. The main scene of this altarpiece, showing the Presentation of Christ in the Temple (now preserved in Siena) was ordered by the Pork-butchers Guild (the Pizzicaiuoli) in 1447. The predella was added later when Catherine was canonized in 1461. In the first panel Catherine kneels before an altar and reaches up to choose from the monastic garments offered by Saints Dominic, Augustine, and Francis, all founders of religious orders. Catherine takes the habit of Saint Dominic, which she wore as the founder of the Sisters of Penance. The second panel shows, at the right, Saint Catherine giving her cloak to a threadbare beggar. The beggar was really Christ in disguise, and at the left he returns the cloak to her. For this act of charity, the cloak perpetually protected its wearer from the cold. | ||

| Among other stories is that of the visit that she paid to Pope Gregory XI in Avignon during which she persuaded the curia to move back to its traditional residence in Rome Saint Catherine died in Rome in 1380. The central panel of the altarpiece, whose predella contained a complex cycle of the life of the saint according to the abbot Carli was a Presentation in the Temple which has been identified as a panel in the Pinacoteca in Siena The altarpiece was commissioned from Giovanni di Paolo in 1447 by the guild of the Pizzicaioli with the intention that it should be finished in 1449. Giovanni di Paolo located the scene in a precise but expressive interior in which the saint and her companion seem overwhelmed by the setting. This impression is conveyed by their small, slender figures in comparison with the size and presence of the members of the curia. The heads are well conceived and the rich decorative motifs that convey the wealth of the papal court at Avignon do not detract from the composition. Despite the ingenious nature of the composition and its construction, the colours and figures create an elegant scene of great force. Various reconstructions have been undertaken of the altarpiece in Santa Maria della Scala and it has also been debated as to whether this predella, with its scenes of Saint Catherine may or may not have belonged to that work, commissioned in 1447 even though Saint Catherine was not canonised until 1461. Mar Borobia |

||

| Sassetta: The Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece, by Machtelt Israels (Editor), James R. Banker (Contributions by), Rachel Billinge (Contributions by), Roberto Bellucci (Contributions by), 2009, Florence & Leiden, Villa I Tatti/ The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies/ Primavera Press. Machtelt Israëls is Researcher in the History of Renaissance and Early Modern Art at the University of Amsterdam. Publisher's summary: Sassetta, the subtle genius from Siena, revolutionized Italian painting with an altarpiece for the small Tuscan town of Borgo San Sepolcro in 1437–1444. Originally standing some six yards high, double-sided, with a splendid gilt frame over the main altar of the local Franciscan church, it was the Rolls Royce of early Renaissance painting. But its myriad figures and scenes tempted the collectors of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and today its disassembled panels can be found in twelve museums throughout Europe and the United States. This book solves the three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle of this masterwork’s reconstruction and, on a firm scientific foundation, restores it to its vivid historical context. To produce this landmark volume, experts in art and general history, painting technique and conservation, woodworking, architecture, and liturgy have joined forces across the boundaries of eight different nations. Letters of Catherine Benincasa by Saint of Siena Catherine | www.gutenberg.org Reconstructed Sassetta altarpiece | Harvard Magazine Nov-Dec 2009 | Christopher Reed, Masterpiece Pieces, 'Investigators construct a virtual fifteenth-century altarpiece The dismantling of this masterpiece for liturgical reasons occurred between 1578 and 1583. Today only 27 of its paintings are known to exist, in 12 museums. But Israëls conceived the notion that the altarpiece could be reconstructed in a different medium because Sassetta’s patrons had given him a scripta, detailed instructions, a document discovered in 1991. Israëls assembled a team of 30 experts—in art and general history, painting technique and conservation, woodworking, architecture, and liturgy, including all scholars studying the artist—from eight countries. They have now produced Sassetta: The Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece, a richly illustrated book edited by Israëls, just published by I Tatti, and distributed by Harvard University Press. Thanks to this remarkable collaboration, what Dutch art historian Henk van Os has called the Rolls-Royce of early Italian Renaissance altarpieces is virtually together again—and gleams.'

|

|||||

[2] Raymond, of Capua. The life of St. Catherine of Siena. Translated by George Lamb. New York, P. J. Kenedy [1960]; According to Henk van Os

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Podere Santa Pia, an ancient small cloister, faces the gentle hills of Maremma Region, offers its guests a breathtaking view over the Tuscan hills. On clear days or evening, one can even see Corsica. | |||||