| |

|

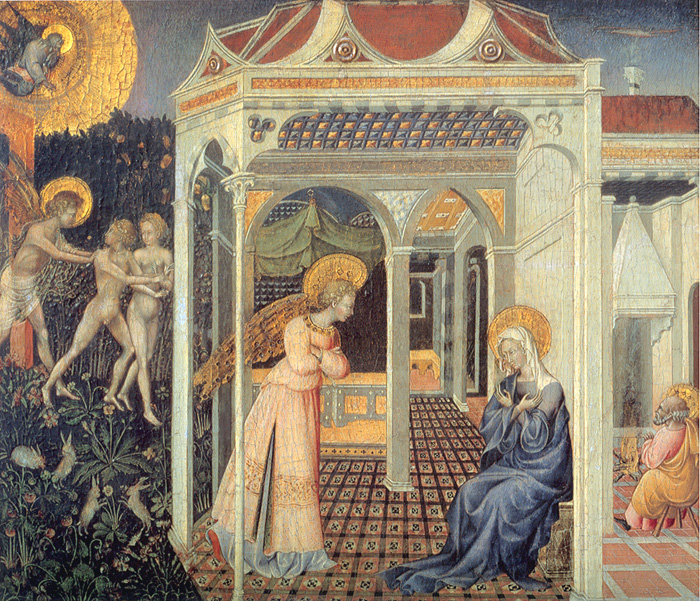

Giovanni di Paolo's brilliant color and pattern were typically Sienese, but he is distinguished from his teachers and contemporaries by an expressive imagination. His unique style is otherworldly and spiritual. Here the drama is heightened by a dark background and contrasting colors, nervous patterns, and unreal proportions. In the center, Gabriel brings news of Christ's future birth to the Virgin. Thus is put in motion the promise of salvation for humankind, a salvation necessitated by the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, which we see happening on the left, outside Mary's jewellike home. Mary will reopen the doors of Paradise closed by Eve's sin. The scene of Joseph warming himself in front of a fire, on the right, is an unusual addition. Perhaps it refers simply to the season of Jesus' birth, but more likely it is layered with other meanings, suggesting the flames of hope and charity and invoking the winter of sin now to be replaced by the spring of this new era of Grace. The three scenes help make explicit the connection between the Fall and God's promise of salvation, which is fulfilled at the moment of the Annunication.

Though Giovanni's primary concern is not the appearance of the natural world, it is clear that he was aware of contemporary developments in the realistic depiction of space. Note how the floor tiles appear to recede, a technique adopted by Florentine artists experimenting with the new science of perspective. |

|

The Annunciation and Expulsion from Paradise, circa 1435, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

The Annunciation and Expulsion from Paradise, circa 1435, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. |

| |

|

|

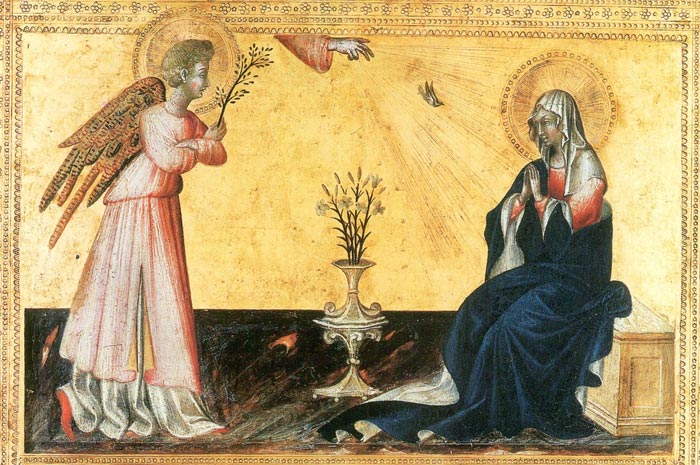

This exquisite panel depicts the Virgin Annunciate, her right arm across her body, her eyes cast down as she receives the tidings. Under her blue mantle she wears a richly ornamented robe of red and gold. Measuring only five inches in height and with an added triangular piece of wood to make this an independent rectangular image, this panel is clearly the upper register of the right-hand shutter of a portable altarpiece. Following its appearance at auction in 2001 where it was described as being by a 'Follower of Lorenzo di Bicci' (see provenance above) it was recognized by Laurence Kanter, Keith Christiansen, Everett Fahy and Michel Laclotte as an autograph work by the Sienese quattrocento master Giovanni di Paolo.

The panel dates from the end of his early maturity. Federico Zeri proposed the reconstruction of shutters of a portable triptych which sets an Archangel Gabriel (Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon) above a Saint James the Major (Mason Perkins collection, Assisi) and places opposite a Saint Christopher (formerly E. Moratilla collection, Paris). The Weisl Virgin Annunciate (unknown to Zeri) then belongs above Saint Christopher. The central panel, probably a Crucifixion, remains untraced. All the panels have been trimmed to some degree: this measures 9.2 cm wide, the Avignon Archangel 10 cm., the Saint Christopher 13.5 cm. and the Saint James 11.5 cm. This arrangement has won universal acceptance and is borne out not only by the subject matter, but by the size, the way the panels of both the Angel and the Virgin have been made up in the same way, and by the identical punchwork and decoration of the gold with the five-petalled flowers in the haloes and the distinctive delicate foliate design on the panel's outer border. In addition, the delicate application of gold ornament to the robes of the Saint Christopher and the Angel exactly match that of the Virgin. Both Saint James Major and Saint Christopher were protectors of travelers, which would make this portable altarpiece iconographically appropriate for the use of merchants or pilgrims.

|

|

Giovanni di Paolo, The Virgin Annunciate, tempera and gold on panel; from the right wing of a portable tabernacle Giovanni di Paolo, The Virgin Annunciate, tempera and gold on panel; from the right wing of a portable tabernacle

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

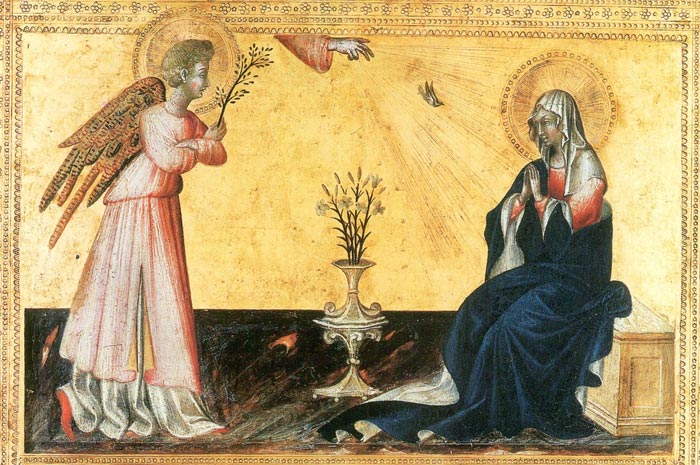

The account books of the most important offices of Siena's medieval municipality had covers made of decorated wooden panels. These were called 'bicherne', named after Bicherna, the financial office that started decorating its manuscripts before any other office did and continued to do so extensively. Production of these decorated book covers started in 1257 and continued until the middle of the fifteenth century. This strange alliance between art and bureaucracy is one of the most original manifestations of Sienese art and involved some of the finest artists.[3]

This Annunciation panel comes from the Gabella Generale (general tax office). It shows the Virgin Mary, seated on a chest with her hands joined in prayer and wrapped in a voluminous cloak. The Archangel Gabriel stands before her with his arms crossed and holding an olive branch in one hand, symbolizing peace. In the middle of the painting, between the figures of Mary and the archangel, is a finely worked vase holding a bunch of lilies. They symbolize Mary's purity and virginity. Above the vase, God's blessing hand sends out rays of light that carry the dove of the Holy Spirit toward Mary.

Art in Tuscany | Sienese Biccherna Covers | Biccherne Senesi |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

[1] Trained in Siena in the early quattrocento, presumably in the circle of artists such as Gregorio di Cecco, Benedetto di Bindo, and Martino di Bartolomeo, Giovanni is documented for the first time in 1417, when he received payment for miniatures in a Book of Hours commissioned by the wife of a Milanese jurist, a member of the Castiglioni family at that time resident in Siena.[1] Possibly in deference to his clients from northern Italy, Giovanni's painting is inspired by examples of late Gothic art from that area, as well as France. However, Giovanni consistently grafted foreign influences onto his own Sienese figurative tradition, producing highly original results. Furthermore, the preciousness of pictorial rendering and attention to naturalistic detail in Giovanni's earliest works appear as an immediate response to Gentile da Fabriano's presence in Siena in 1425-1426. This is evident in his paintings for the church of San Domenico in Siena (Christ Suffering and Triumphant, now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, no. 212); the Pecci polyptych of 1426, whose central panel is in the Propositura in Castelnuovo Berardenga, with others in the Siena Pinacoteca (nos. 193 and 197) and elsewhere; and the Branchini polyptych of 1427, whose central panel is now in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena.

In subsequent years the artist also felt the influence of the reliefs of the Siena baptistry font, especially those by Jacopo della Quercia, Donatello, and Ghiberti. But again, he interpreted the early Renaissance style of these prototypes with an almost expressionistic exasperation of rhythms, and combined their motifs in his own rather unconventional arrangements, giving strongly individual harsh expressions to the faces and actions. Examples of this phase are the Virgin of Mercy of 1431 (Santa Maria dei Servi, Siena); the Osservanza Crucifixion of 1440 (Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, no. 200); the triptych in Sant'Andrea in Siena dated 1445; the polyptych in the Galleria degli Uffizi also dated 1445; and the Pizzicaioli altarpiece of c. 1447-1449, whose central panel is also in the Siena Pinacoteca.

In his numerous works executed in the middle two decades of the century, Giovanni framed his fantastic narrative vein in structures that were defined with a sort of capricious pseudo-perspective, and reintroduced the elongated elegant forms of late Gothic art. At the same time, however, he sought effects of monumentality and plasticity in response to painters of the younger generation. In this period he created numerous masterpieces: the Creation and Expulsion from Paradise and Paradise (both in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York), which originally may have belonged to the Uffizi polyptych of 1445; eleven panels with scenes from the life of Saint John the Baptist, divided among the Art Institute of Chicago, Landesmuseum in Münster, Metropolitan Museum, Musée du Louvre, and Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena; the Saint Nicholas polyptych of 1453 in the Pinacoteca in Siena (no. 173); and the predella with stories from the legend of Saint Catherine of Siena, divided among the Cleveland Museum of Art, Detroit Institute of Arts, Metropolitan Museum, Rijksmuseum in Utrecht, and private collections. Even in late works like the altarpiece in the duomo of Pienza of 1463, the quality of his work is still very high. It is only in the last years of his activity, for example in the polyptych from Staggia now in the Pinacoteca in Siena, dated 1475 (nos. 186-189, 324), that Giovanni begins to show signs of slowing down and entrusts to his workshop the repetition of his habitual formulas. "As he developed, his style inevitably changed," observes Pope-Hennessy in his reconsideration of the art of Giovanni di Paolo fifty years after the publication of his monograph on the painter, "but his imagery remained constant and his work from the first to last possesses a highly individual imaginative quality. He relives the scenes he represents with such intensity that we see them through his mind and with his eyes."[2]

[This is the artist's biography published, or to be published, in the NGA Systematic Catalogue]

[1] Ingeborg Bähr, "Die Altarretabel des Giovanni di Paolo aus S. Domenico in Siena," MittKIF 31 (1987): 357-366.

[2] Pope-Hennessy 1988, 6.

Art in Tuscany | Sienese Biccherna Covers | Biccherne Senesi

Siena is dominated even today by its cathedral, a dazzling facade of dark and light stone. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the centerpiece of its interior was a gold and brilliantly colored monumental altarpiece—Duccio's Maestà, some panels of which are in the Gallery's collection. Both the fame of the Maestà, which drew large numbers of pilgrims to Siena, and Duccio's influence as a teacher had a long-lived impact on the style of Sienese art. While painters in nearby Florence adopted rounder, more realistic forms, most Sienese artists in the early fourteenth century continued to prefer Duccio's linear and decorative style, which used gold and strong color to create pattern and rhythm.

Probably among Duccio's students was Simone Martini, whose reputation led him to work for the French king of Naples and for the pope, then living in Avignon. Through Simone the brilliant colors and rich patterns of Sienese art met the graceful and lyrical figures of French manuscript painting, evolving to form the International Style. Its refined and courtly manner dominated the arts across Europe at the end of the Middle Ages. Simone's chief competitors in Siena were the brothers Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti, whose influence can also be seen on this tour. Like Simone they were probably assistants in Duccio's workshop, but while Simone painted with refined elegance, the Lorenzetti were concerned with the definition of three-dimensional space, narrative detail, and the depiction of everyday life.

In the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, a greater emphasis on human experience and perceptions prompted artists of many kinds to begin "speaking in the vernacular." Poets in Sicily invented and perfected the sonnet, and Dante wrote the Divine Comedy—not in Latin but Italian. Also for the first time, sermons were given in native Italian dialects by members of influential new religious orders, particularly the Franciscans and Dominicans, who left the shelter of monasteries to preach in cities and towns. Religion focused increasingly on human and humane concerns. The simple virtues of the early Franciscans—who renounced worldly possessions and identified strongly with Christ and his suffering—helped to shift emphasis onto Christ's human nature and to demand of religious art a new and closer identification with people's experience. Artists responded by enhancing the sense of particular time and place with detailed settings familiar to their viewers, by expanding the range of gesture and emotion, and by embroidering their narratives with anecdotal details.

|

|

|