|

|

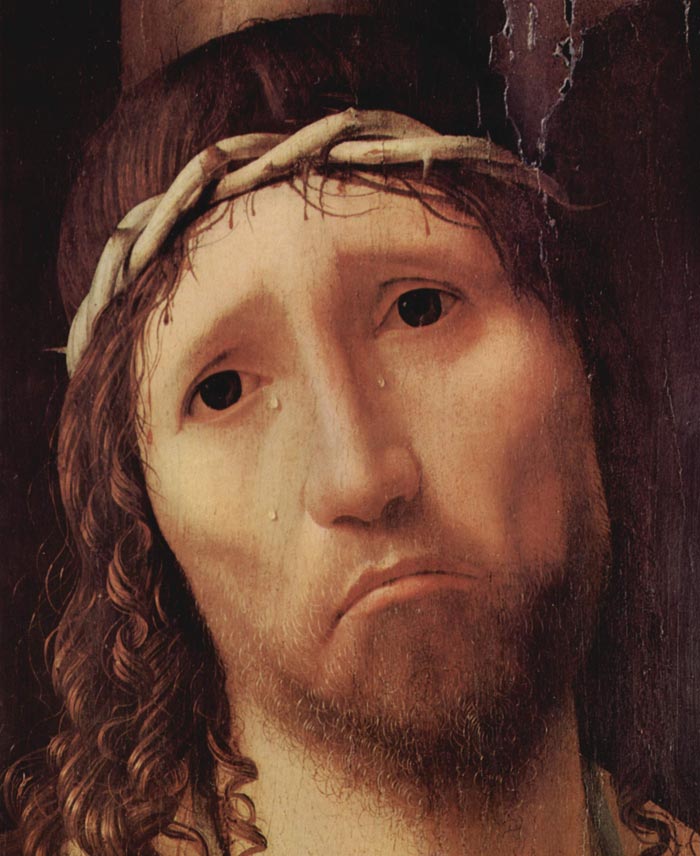

Antonello da Messina, Ecce Homo, 1473, Collegio Alberoni, Piacenza |

|

Antonello da Messina, Ecce Homo |

Antonello da Messina (ca. 1430–1479) was one of the most groundbreaking and influential painters of the quattrocento. His formation took place in Naples during the rule of Alfonso of Aragon, in a brilliant artistic climate open to French and Netherlandish painting. Antonello absorbed these influences, so much so that many of his near contemporaries believed he was the first to introduce the use of oil painting—already current in the North—in Italy. His trip to Venice in 1475 was a landmark occasion, and his great altarpiece for the church of San Cassiano there (now in fragmentary form in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) redirected the art of Giovanni Bellini and other Venetian painters, while his portraits mark a new stage in the evolution of that genre in Italy. No greater artist emerged from southern Italy in the fifteenth century.[1] |

| Christ Crowned with Thorns was in a collection in Palermo by the seventeenth century, when the date 1470 was recorded as appearing on the cartellino at the base. The date would make this the earliest extant version of a subject that Antonello treated frequently. Christ is shown bust-length, behind a parapet—a convention appropriated from portraiture and used to enhance the effect of his physical presence.

Christ Crowned with Thorns (possibly 1470) from The Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection has a profound impact on the viewer due to the immediacy of the painting's bust-length format inspired by similar Flemish works. A bare-chested Christ crowned with thorns is shown isolated behind a ledge. His facial features are in no way idealized or classically beautiful, emphasizing his humanity. And the expression of suffering on Jesus' anguished visage does not detract from the figure's sense of dignity. Despite certain abrasions to the panel's surface, Antonello's subtle modeling of Christ's nose and upper torso is still visible today. |

||||

| While the New York Ecce Homo , dated 1470, shows the intense sentimentalism typical of the Flemish interpretation of the subject, the one from Piacenza, executed in 1475, reveals the change that occurred after his contact with the artistic scene in Venice, when he began to acquire a dramatic and expressive force so strong as to influence later painters. | ||||

Antonello da Messina, Madonna and Child with a Praying Franciscan Donor (recto), 1450s or early 1460s, Museo Regionale Messina |

|

|||

Rediscovered in 2003, a double-faced painting provides a fascinating vision into the artist's training and earliest years.

The two small private devotional works from Messina and New York, which are painted on both sides and appear worn with use, are characterized by an expert descriptive skill that is almost miniaturist, especially the very intense Ecce Homo from New York (recto). These paintings, though so small in size, reveal Antonello's masterly art in capturing profound emotions through a penetrating study of reality.

|

||||

|

|

|||

Ecce Homo (c. 1473) - Tempera on panel, 19.5 x 14.3 cm, Private collection, New York City |

||||

|

||||

Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari | Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects | Antonello da Messina Antonello da Messina | Scuderie del Quirinale The ‘Antonello da Messina’ exhibition, scheduled at the Scuderie del Quirinale from 18 March to 25 June 2006, was a unique event, bringing together – for the first time in history – virtually all of Antonello’s paintings that have come down to us. Galleria Nazionale Palazzo Spinola, Genua | www.palazzospinola.it The museum was conceived with the artwork, furnishings, ceramics, silver, books and etchings which the marquis Paolo and Franco Spinola donated in 1958 to the Italian State together with the centuried family mansion of which the aforementioned constituted patrimony. |

||||

This page uses material from the Wikipedia articles Antonello da Messina and Ecce Homo published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

|

||||

Antonello da Messina (1430–1479), Ecce Homo, 1474, oil on panel, 39.7 × 32.7 cm (15.6 × 12.9 in), Galleria Spinola, Genua

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

San Gimignano |

Podere Santa Pia, giardino |

Podere Santa Pia |

||

|

||||

The abbey of Sant'Antimo |

Cortona |

Spoleto, Duomo |

||

|

|

|||

Crete Senesi, surroundings of Podere Santa Pia |

Abbazia di Monte Oliveto Maggiore |

Abbadia d’Ombrone and Monastero d’Ombrone near Castelnuovo Berardenga. |

||