| |

|

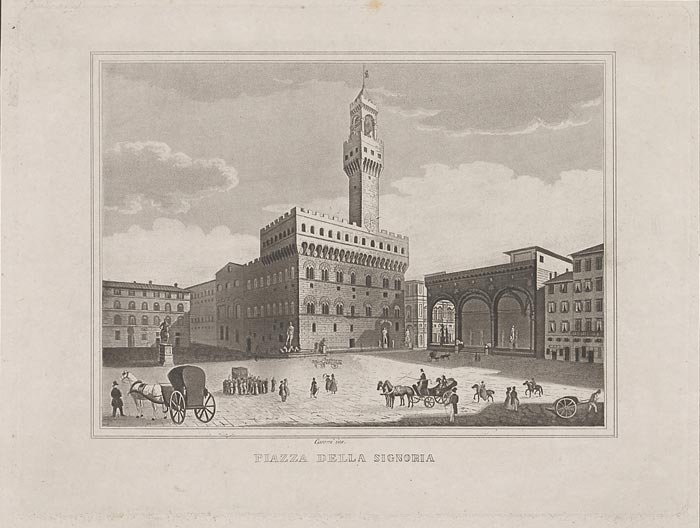

Het Piazza della Signoria is omringd door verschillende beroemde Palazzo's, stadspaleizen. Het meest bekende paleis van Florence is ongetwijfeld het oude stadhuis Palazzo Vecchio maar rondom het plein ziet u de prachtige gevels van andere vaak 16de-eeuwse gebouwen.

Voor Palazzo Vecchio staat een standbeeld van Cosimo I van Giambologna (1594) en een fontein van Neptunus van Bartolomeo Ammannati (1575). Hier werd in 1498 de prediker Girolamo Savonarola opgehangen en verbrand wegens het verbranden van o.a. boeken op hetzelfde plein.

Palazzo Vecchio

Het meest in het oog springende gebouw aan de Piazza della Signoria is het oude paleis Palazzo Vecchio. Het gebouw is tussen 1298 en 1314 gebouwd en in latere eeuwen verder uitgebouwd. Tegenwoordig is er een museum gevestigd. Alleen het gebouw al is een bezoek waard. In tegenstelling tot andere musea in Florence hoeft u voor het bezoek aan de Palazzo Vecchio niet in de rij te staan. De begane grond en de binnenplaats kunt u zelfs gratis bezoeken.

Vanaf de boven verdieping van het Palazzo Vecchio heeft u een prachtig uitzicht op het oude centrum en de Duomo.

De Loggia dei Lanzi is een open loggia, die oorspronkelijk gebouwd werd om bestuurders en hun gasten tijdens plechtigheden te beschutten tegen de regen. In 1583 werd het dak van de loggia omgebouwd tot een terras dat verbonden werd met het Uffizi paleis. Zo konden de Medici de gebeurtenissen en evenementen op het plein van bovenaf aanschouwen.

Naast de Loggia dei Lanzi is een korte zijstraat naar de rivier de Arno en de Ponte Vecchio. In deze straat staat het wereldberoemde Uffizi museum.

|

|

| |

De Loggia dei Lanzi

|

|

|

De Loggia dei Lanzi is een beeldengalerij op het Piazza della Signoria. De galerij werd tussen 1376 en 1382 gebouwd door Benci di Cione en Simone Talenti en bevat een aantal bekende beeldhouwwerken, waaronder:

De Sabijnse maagdenroof (Giambologna, 1583)

Hercules en de Centaur (Giambologna, 1599)

Perseus en Medusa (Benvenuto Cellini, 1554)

De roof van Polyxena (Pio Fedi)

Menelaos bij het lichaam van Patroclus

Gebouwd op een ogenblik dat de gotische spitsbogen nog in de mode waren, is de Loggia met haar ronde bogen een terugblik op de klassieke oudheid en een voorafbeelding van wat de Renaissance zal bieden. Ze is een voorloper van Brunelleschi's revolutionaire architectuur.

De arcadengalerij is genoemd naar de lanzichenecchi (lansknechten), de Zwitserse lijfwachten van Cosimo I. Het was deze groothertog die in 1560 de opdracht gaf voor het meest prestigieuze beeld van de loggia, de bronzen Perseus van Cellini. Het beeld was bedoeld om de vijanden van Cosimo te waarschuwen voor het lot dat hen te wachten stond.

De Sabijnse maagdenroof is het werk van Giambologna, die als Jean de Boulogne geboren werd in Dowaai, dat toen tot het graafschap Vlaanderen behoorde. De worstelende figuren van een oude man, een jongeling en een vrouw werden uit één stuk marmer gehouwen. Het is een der eerste beelden bedoeld om van alle zijden bekeken te worden.

De galerij is dag en nacht vrij toegankelijk en wordt onderhouden door het Uffizi.

Aan de Odeonsplatz in München werd in 1841-1844 in opdracht van koning Ludwig I een kopie van de loggia gebouwd, de Feldherrnhalle.

|

|

Menelaus ondersteunt het lichaam van Patroclus, een vaak gerestaureerd Romeins beldhouwwerk Menelaus ondersteunt het lichaam van Patroclus, een vaak gerestaureerd Romeins beldhouwwerk

|

|

Perseus en Medusa (Benvenuto Cellini, 1554)

|

Underneath the bay on the far left is the bronze statue of Perseus by Benvenuto Cellini. [4] Perseus with the head of Medusa, also known as Cellini’s Persus, is a bronze sculpture. It is considered a masterpiece of Italian Mannerism, and is one of the most famous statues in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria. The statue depicts Perseus as he stands on Medusa’s body and holds her head up in the air. In the scene, he has just beheaded her with his sword, and triumphantly lifts up her head, holding it by her hair. The statute has a rather high pedestal, adorned with small bronzes that are now at the Bargello museum, so that the spectator must look up at it as Perseus looks down toward the ground. The refined pedestal bronzes are an example of Cellini’s unparalleled talent when working on smaller pieces. This was due to the fact that he was also an expert goldsmith.

The statute was commissioned by Cosimo I dei Medici, after he had just been named Grand Duke, and was completed from 1545 to 1554. The original still stands in the Loggia today.

The richly decorated marble pedestal, also by Cellini, shows four graceful bronze statuettes of Jupiter, Mercurius, Minerva and Danaë. The bas-relief on the pedestal, representing Perseus freeing Andromeda, is a copy of the one in Bargello.

Benvenuto Cellini worked almost ten years on this bronze (1545-1554). His wax design was immediately approved by Cosimo I de' Medici. He met numerous difficulties which, according to his autobiography, almost brought him to the brink of death. The casting of this bronze statue was several times unsuccessful. When attempting again, the melting furnace got overheated, spoiling the casting of the bronze. Cellini gave orders to feed the furnace with his household furniture and finally with about 200 pewter dishes and plates, and his pots and pans. This caused the bronze to flow again. After the bronze had cooled, the statue was miraculously finished, except for three toes on the right foot. These were added later. |

|

Perseus en Medusa (Benvenuto Cellini, 1554). The statue of Perseus by Cellini depicts a decapitation that was intended as a warning to enemies of Cosimo I

|

On the far right is the manneristic group Rape of the Sabine Women by the Flemish artist Jean de Boulogne, better known by his Italianized name Giambologna. [5] This impressive work was made from one imperfect block of white marble, the largest block ever transported to Florence. The goccia model is now in the Galleria dell' Academia. [6] Giambologna wanted to create a composition with the figura serpentina, an upward snakelike spiral movement to be examined from all sides. This is the first group representing more than a single figure in European sculptural history to be conceived without a dominant viewpoint. It can be equally admired from all sides. The marble pedestal, also by Giambologna, represents bronze bas-reliefs with the same theme. This marble and bronze group is in the Loggia since 1583.

Nearby is Giambologna's less celebrated marble sculpture Hercules beating the Centaur Nessus (1599) and placed here in 1841 from the Canto de' Carnesecchi. It was sculpted from one solid block of white marble with the help of Pietro Francavilla

The group Menelaus supporting the body of Patroclus, discovered in Rome stood originally at the southern end of the Ponte Vecchio. There is another version of this much-restored Roman marble in the Palazzo Pitti. It is an ancient Roman sculpture from the Flavian era, copied from a Hellenistic Pergamene original of the mid third century BC. This marble group was discovered in Rome. It has undergone restorations by Ludovico Salvetti, to a model by Pietro Tacca (1640) and by Stefano Ricci (about 1830).

The group The Rape of Polyxena, is a fine diagonal sculpture by Pio Fedi from 1865.

|

|

Giambologna, De Sabijnse maagdenroof (detail) |

The Loggia della Signoria also houses the Hercules Fighting the Centaur Nessus, commissioned to Giambologna by Grand Duke Ferdinand I around 1594.

Compared to the Rape of the Sabine Women, this group is constructed from a less dynamic stance.

The front viewpoint conditions the onlooker; in fact, only from this view is it possible to appreciate the contrast between Hercules' face and the wild, savage face of the centaur, Nessus; the movement of the hero's body is contrasted by the emphatic movement of the monster's trunk, which bends back diagonally. In actual fact, the group was originally designed to be placed on a pedestal at the crossroads in Canto dei Carnesecchi and it was placed under the Loggia in the mid-19th century.

The reference that the sculptor wished to surpass was that of sculpting something similar to the famous sketch (now in Berlin) of Hercules and Cacus by Baccio Bandinelli: a project conceived around an epic fight, where the semigod holds down his enemy, who has been struck down, but who continues to struggle. The overly emphatic gestures for the weights and volumes that needed to be created using a colossal block of stone led to a second solution by Bandinelli, which now stands in Piazza Signoria. Giambologna started from Bandinelli's revolutionary sketch, which could be seen in the collection of the Grand Dukes in Palazzo Vecchio, rendering it more malleable through a better design, based on a calculated movement of the limbs away from the centre of gravity.

|

|

Giambologna, Hercules en de Centaur Nessus, 1599, Loggia dei Lanzi

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Giambologna, Hercules en de Centaur Nessus, 1599, (detail), Loggia dei Lanzi

|

| On the back of the Loggia are five marble female statues (three are identified as Matidia, Marciana and Agrippina Minor), [7] Sabines and a statue of a barbarian prisoner Thusnelda from Roman times from the era of Trajan to Hadrian. They were discovered in Rome in 1541. The statues had been in the Medici villa at Rome since 1584 and were brought here by Pietro Leopoldo in 1789. They all have significant, modern restorations.

The Feldherrnhalle in Munich, the site of a failed coup by the fledgling Nazi party in 1923, was modelled after the Loggia dei Lanzi. |

|

|

|

| |

|

Art in Tuscany | Churches in Firenze | The Basilica della Santissima Annunziata

Walking in Tuscany | Florence | Walking in the Bargello Neighbourhood

John Pope-Hennessy, Benvenuto Cellini, Paris, 1985.

[0] Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz | Squares

Address: Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, Via Giuseppe Giusti 44, 50121 Firenze

[1] a b c Zucconi, Guido (1995). Florence: An Architectural Guide. San Giovanni Lupatoto, Vr, Italy: Arsenale Editrice srl. ISBN 88-7743-147-4.

[2] loggia. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

[3] Gaddi, Agnolo. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

[4] Florence. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

'Perseus with the head of Medusa, also known as Cellini’s Persus, is a bronze sculpture. It is considered a masterpiece of Italian Mannerism, and is one of the most famous statues in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria. Located in the Loggia dei Lanzi, it depicts Perseus as he stands on Medusa’s body and holds her head up in the air. In the scene, he has just beheaded her with his sword, and triumphantly lifts up her head, holding it by her hair. The statute has a rather high pedestal, adorned with small bronzes that are now at the Bargello museum, so that the spectator must look up at it as Perseus looks down toward the ground. The refined pedestal bronzes are an example of Cellini’s unparalleled talent when working on smaller pieces. This was due to the fact that he was also an expert goldsmith.

The statute was commissioned by Cosimo I dei Medici, after he had just been named Grand Duke, and was completed from 1545 to 1554. The original still stands in the Loggia today. It has stood there since its completion in 1554, except for a period of restoration that ended in 1998. Cellini’s Perseus recalls Donatello’s bronze sculpture Judith and Holofernes (1460), but Cellini takes a step away from the early Renaissance style towards the characteristic titanism of the Italian Mannerism. Cellini’s Perseus also has political meaning, just like the vast majority of the statuary in the piazza. Indeed, it represents the new Grand Duke’s desire to break away from experiences of the earlier republic and send a message to the people, which are represented by Medusa. Serpents emerge from Medusa’s body, representing the people’s many past conflicts that had only worked to threatened and obstruct true democracy. Making the statue proved extremely difficult for Cellini, who truly put his talents to the test. He often spoke of his difficulty with Perseus in his autobiography. He complained about the difficulty fusing the statue in his kiln, and how he used all of the dishware in his home to make it. Fun fact: It is believed that Cellini used a young lover as his model for the statute, and on the back of Perseus’ neck, there is the small portrait of a bearded man, which many maintain is Cellini himself. Florentine singer-songwriter Riccardo Marasco sings about this statue in a song called “L’alluvione” from his album "Il porcellino".' [Se also www.turismo.intoscana.it]

[5] Giambologna. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

Giambologna was born in Douai, Flanders (now in France). After youthful studies in Antwerp with the architect-sculptor Jacques du Broeucq,[1] he moved to Italy in 1550, and studied in Rome. Giambologna made detailed study of the sculpture of classical antiquity. He was also much influenced by Michelangelo, but developed his own Mannerist style, with perhaps less emphasis on emotion and more emphasis on refined surfaces, cool elegance and beauty.

[6] Copy of the rape of the Sabine Woman

The Rape of the Sabine Women is an episode in the legendary history of Rome in which the first generation of Roman men acquired wives for themselves from the neighboring Sabine families. The English word "rape" is a conventional translation of Latin raptio, which in this context means "abduction" rather than its prevalent modern meaning of sexual violation. Recounted by Livy and Plutarch (Parallel Lives II, 15 and 19), it provided a subject for Renaissance and post-Renaissance works of art that combined a suitably inspiring example of the hardihood and courage of ancient Romans with the opportunity to depict multiple figures, including heroically semi-nude figures, in intensely passionate struggle.

The Rape is supposed to have occurred in the early history of Rome, shortly after its founding by Romulus and his mostly male followers. Seeking wives in order to found families, the Romans negotiated unsuccessfully with the Sabines, who populated the area. Fearing the emergence of a rival society, the Sabines refused to allow their women to marry the Romans. Consequently, the Romans planned to abduct Sabine women. Romulus devised a festival of Neptune Equester and proclaimed the festival among Rome's neighbours. According to Livy, many people from Rome's neighbours attended, including folk from the Caeninenses, Crustumini, and Antemnates, and many of the Sabines. At the festival Romulus gave a signal, at which the Romans grabbed the Sabine women and fought off the Sabine men. The indignant abductees were soon implored by Romulus to accept Roman husbands.

Livy is clear that no sexual assault took place. On the contrary, Romulus offered them free choice and promised civic and property rights to women. According to Livy, Romulus spoke to them each in person, "and pointed out to them that it was all owing to the pride of their parents in denying the right of intermarriage to their neighbours. They would live in honourable wedlock, and share all their property and civil rights, and—dearest of all to human nature—would be the mothers of free men."[Livy: The Rape of the Sabines]

[7] Giovanna Giusti Galardi, The Statues of the Loggia Della Signoria in Florence

[8] Source: Il Giambologna a Firenze | www.giambologna.comune.fi.it

|

This article incorporates material from the Wikipedia articles Loggia dei Lanzi and Pucci family published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Loggia dei Lanzi

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia, situata sulle splendide colline del valle d'Ombrone nel cuore della Maremma

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Podere Santa Pia, giardino |

|

Podere Santa Pia |

|

Montecristo, vista da Podere Santa Pia

|

|

|

|

|

|

Val d'Orcia" tra Montalcino Pienza e San Quirico d’Orcia. |

|

Corridoio Vasariano, Firenze |

|

Massa Marittima |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Orvieto, Duomo |

|

Siena, Duomo |

|

Florence, Duomo Santa Maria del Fiore |

| |

|

|

|

|

De Pucci familie

|

|

|

De lange rechte straat, die de Piazza dei Duomo met de Piazza dei la Santissima Annunziata verbindt, is de Via dei Servi. Ze ontleent haar naam aan de Servi di Maria, de dienaren van Maria of de servieten, de stichters van de Santissima Annunziata.

Omdat de naam van de familie oorspronkelijk 'Saracini' zou zijn geweest, staat in het wapenschild van de Pucci de kop van een moor in profiel, symbool voor de moren die tijdens de kruistochten of op de galeien op zee gevangen werden genomen. Op zijn hoofd heeft de moor een zilveren haarband waarin driemaal de letter T staat, afkortingen voor 'Tempori - Tempora - Tempere', wat zoveel betekent als 'geef de tijd zijn tijd'. Eigenlijk zouden die T's echter hamers hebben voorgesteld die verwezen naar het oorspronkelijke beroep van de familie, namelijk (scheeps )timmerlieden.

In de Via dei Pucci zou vanaf april 1863 voor meer dan een jaar de Russische revolutionair en een van de grondleggers van het anarchisme, Michael Bakoenin, hebben verbleven, maar er hangt geen gedenkplaat. Zijn gedachtegoed verspreidde zich van hieruit over heel Toscane.

Patronage

|

|

Het wapenschild van de Pucci: de kop van een moormet een zilveren haarband waarin driemaal de letter T staat, Tempore tempora temperar [1]) |

In 1404 Antonio di Puccio Pucci acquired the chapel of San Sebastiano in the church of Santissima Annunziata, in which he placed the precious Piero del Pollaiolo painting of the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (now in the National Gallery, London). Puccio Pucci bought the Cappella della Madonna del Soccorso a few decades later.

The family palazzo still contains one of the four paintings commissioned by Lorenzo the Magnificent from Sandro Botticelli as a gift to Giannozzo Pucci on Giannozzo's marriage to Lucrezia Bini in 1483. These paintings tell the story of Nastalgio degli Onesti and the first three in the narrative are now in the Prado in Madrid. The painting still in Florence shows the use of forks, which were traditionally adopted for the first time in Florence by the Pucci and whosa use Catherine de'Medici then spread right across Europe. It also shows the use of precious tableware and silver vessels, which really existed and were said to be from the workshops of Verrocchio and Pollaiolo.

The Pucci commissioned several works for the churches neighbouring their palazzo. For the church of San Michele Visdomini, in 1518 Francesco Pucci commissioned Pontormo to paint the Holy family with saints, which was described by Vasari as one of the best paintings by an empolese painter. Whilst he was archbishop of Bologna, cardinal Antonio Pucci commissioned Raphael to paint a scene of The Ecstacy of Saint Cecilia - still in Bologna, it is now at the city's Pinacoteca. At the end of the 16th century Lorenzo Pucci commissioned Alessandro Allori to paint a Marriage at Cana as an altarpiece for the church of Sant'Agata (completed 1600).

The family's palazzo was rebuilt by the grand-ducal architect Bernardo Buontalenti in the second half of the 16th century. Between 1585 and 1595 abbot Alessandro Pucci built the Villa di Bellosguardo, to designs by Giovanni Antonio Dosio - it remained a family property until 1858. The Pucci completed the portico of the church of Santissima Annunziata, in a stylistic unity with the piazza outside (the Pucci device is to be seen on the pavement in front of the entrance and on both sides of the portico) - an inscription on the frieze and a plaque on Via Gino Capponi gives its completion date as 1601.

[Bibliography

| Marcello Vannucci, Le grandi famiglie di Firenze, Newton Compton Editori, 2006]

De samenzwering

|

|

Sandro Botticelli and Bartolomeo di Giovanni, fourth episode of Nastagio degli Onesti series, private collection in Palazzo Pucci, Florence (1483)

|

Wanneer men van de dom komt, is de eerste straat links de Via dei Pucci waar op nummer 6 het Palazzo Pucci ligt, waarmee een fraai verhaal verbonden is.

Het ging de familie Pucci voor de wind. Er was een Pucci getrouwd met de zus van paus Paulus III Farnese, Lorenzo Pucci was tot kardinaal benoemd door paus Leo X de' Medici, van wie het wapenschild op de hoek met de Via dei Servi te zien is, Roberto Pucci was stadsbestuurder en nadien eveneens kardinaal. Het geslacht onderhield al geruime tijd loyale vriendschapsbanden met de Medici, waaraan abrupt een einde kwam. In 1560 werden ze elkaars aartsvijanden toen Roberto's zoon, Pandolfo, door de Medici ten onrechte werd beschuldigd van immoreel gedrag en niet langer welkom was aan hun hof. Pandolfo, die gehuwd was met de dochter van de historicus Francesco Guicciardini, was zo woedend dat hij wraak zwoer en sluipmoordenaars inhuurde om Cosimo I om het leven te brengen. Het complot zat vrij goed in elkaar en de huurmoordenaars zouden zich verborgen houden op de benedenverdieping van het Palazzo Pucci, achter het eerste raam vlak om de hoek met de Via dei Servi. Daar zouden ze wachten tot Cosimo voorbijkwam, die zich naar de Santissima Annunziata begaf. Wanneer hij passeerde. zouden ze ongezien het vuur kunnen openen en missen was vrijwel uitgesloten. Kennelijk was Pandolfo te loslippig en functioneerde Cosimo's inlichtingendienst beter dan de samenzweerders hadden bevroed, want hij kreeg lucht van het plan. Pandolfo werd voor de rechtbank geleid en veroordeeld tot ophanging vanuit de ramen van het Bargello. Toen de straf was uitgevoerd, bleef Cosimo zich zoals voorheen over deze weg naar de kerk begeven, maar elke keer wanneer hij langs de Via dei Pucci kwam, schoot de nare herinnering hem door het hoofd en voelde hij zich niet meer veilig. Hij liet daarom het bewuste raam dichtmetselen.

Enkele jaren later zon Panootto's zoon Orazio op wraak. Hij zou de hele familie De' Medici uilnodigen op een bal en wilde de groothertog met een dolk te lijf gaan, maar ook dat kwam aan het licht. Orazio probeerde zelfmoord te plegen met de dolk waarmee hij Cosimo had willen uitschakelen, maar werd ontwapend door diens lijfwachten en, net als zijn vader jaren eerder, opgehangen uit de ramen van hetBargello. De bezittingen van de Pucci werden geconfisqueerd, maar later door Ferdinand I teruggegeven. [1]

Art in Tuscany | The conspiracy

|

|

Leonardo da Vinci, tekening van de opgehangen Pazzi samenzweerder Bernardo di Bandino Baroncelli, 1479 |

| [1] Luc Verhuyck, Firenze. Een anekdotische reisgids voor Florence, Amsterdam, Athenaeum – Polak & Van Gennep, 2006.Zie ook V&A Museum - Hidden Histories

|

|

|

Wandelen in de omgving van de Duomo Piazza Signoria

|

|

|

Begin begint op de Piazza del Duomo, het religieuze centrum van Firenze, waar de Duomo , de doopkapel, het bisschoppelijk paleis en de klokkentoren van Giotto zich bevinden.

Wandelen in Toscane | Firenze | Quarter Duomo and Signoria Square (eng)

|

|

|

Lastra a Signa- Villa di Bellosguardo

|

|

|

De Villa di Bellosguardo maakte deel uit van een landgoed dat door de familie Puccvi gekocht werd in 1540. De naam van de villa is afgeleid van het spectaculaire panorama waar het op uitkijkt.

Door een reeks ingewikkelde politieke gebeurtenissen duurde het tot 1585 tot de abt Alessandro Pucci aan de architect Giovanni Antonio Dosio de opdracht gaf de twee gebouwen op het landgoed te herstructureren en het park te herontwerpen.

Eén van de gebouwen diende als residentie voor de Pucci, terwijl de andere gebruikt werd voor agrarisch gebruik. De twee gebouwen werden verbonden door een lange muur. De villa werd compleet geschilderd, ook de buitenkant, door Giovanni Balducci terwijl de tuin en het park verrijkt werden met talrijke beelden van dieren.

De villa behoorde toe aan de familie Pucci tot aan het einde van de negentiende eeuw. In 1906 werd de villa gekocht door de beroemde Italiaanse tenor Enrico Caruso, die gefascineerd was door het panorama en de schoonheid van het park.

Sinds 1955 is de villa eigendom van de stad Lastra a Signa. Het wordt gerund door de Villa Caruso Association, die concerten en andere voorstellingen, tentoonstellingen en bezoeken organiseert. |

| |

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()