| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| Firenze| Duomo, of de Basilica di Santa Maria dell Fiore

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Firenze | The Duomo of Santa Maria del Fiore

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The CATHEDRAL ("Duomo") is dedicated to Santa Maria del Fiore and is of typical Italian Gothic architecture. The present building was designed by Arnolfo di Cambio (1245-1302), one of the greatest architect/sculptors of his age. Finished around 1367 it was completely covered with coloured marble like the earlier Baptistery, earlier Baptistery, although the uncompleted facade was given its covering in the nineteenth century.

In contrast with structure's taut Gothic style, which is completely different from medieval buildings north of the Alps, there are several classic and important works of art. Of primary importance are the two frescoes on the right-hand wall showing the equestrian monuments of the "condottieri" (generals) by Paolo Uccello (1436) and Andrea del Castagno (1456).

Many of the sculptures from the Duomo are now kept in the Museum of the "Opera del Duomo" but others are still in place, such as the lunettes by Luca della Robbia above the doors of the Sacristy or the bronze door of the Mass Sacristy and the great Pietà by Michelangelo. The splendid stained glass windows should not be forgotten, mainly executed from 1434-1445 to the designs of such important artists as Donatello, Andrea del Castagno and Paolo Uccello. Also notable are the wooden inlays of the Sacristy cupboards to the designs of Brunelleschi, Antonio Del Pollaiolo and others.

Filippo Brunelleschi started in 1420 with the construction of the CUPOLA. The diameter of the inner span (m. 41.50) is close to the maximum limit for any kind of masonry dome. Instead of re-using usual methods, Brunelleschi invented a technique based on his knowledge of the Roman's "way of building," which he put at the service of a new concept and new kinds of technical, cultural, aesthetic problems, involved in the realization of the cupola. Basically, the construction of the dome depended on the use of a building technique capable of avoiding any dangerous discontinuity in the 27,000 tons of masonry. The cupola was thus built as a self supporting growing form. The dome is surprisingly modern: in this double shell, the lighter exterior cupola protects the inner cupola from the elements, while the two work together thanks to the powerful connecting ribs. Completed in 1436, the Cupola is the most characteristic feature of the Florentine skyline, symbolising a great cultural tradition and the city's civic awareness. There is a well-known painting of Dante with scenes from the divine comedy, a very plain fresco by Paolo Ucello of English statesman, John Hawkwood and the vault of the cupola, painted by Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) and Federico Zuccari (c. 1540-1609) with a huge fresco representing the Last Judgement. |

| |

Against the left-aisle wall are the only frescoes besides the dome in the Duomo. The earlier one to the right is the greenish Memorial to Sir John Hawkwood (1436), an English condottiere (mercenary commander) whose name the Florentines mangled to Giovanni Acuto when they hired him to rough up their enemies. Before he died, or so the story goes, the mercenary asked to have a bronze statue of himself riding his charger to be raised in his honor. Florence solemnly promised to do so, but, in typical tightwad style, after Hawkwood's death the city hired the master of perspective and illusion, Paolo Uccello, to paint an equestrian monument instead – much cheaper than casting a statue in bronze. Andrea del Castagno copied this painting-as-equestrian-statue idea 20 years later when he frescoed a Memorial to Niccolò da Tolentino next to Uccello's work.

Near the end of the left aisle is Domenico di Michelino's Dante Explaining the Divine Comedy (1465).

Domenico di Michelino named himself after his master, a certain Michelino. He had his painterly training under Fra Angelico whose assistant he also became. His style is similar to that of Filippo Lippi and Pesellino.

Dante, poised between the mountain of purgatory and the city of Florence, displays the famous incipit Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita in a detail of Domenico di Michelino's painting, Florence 1465.

In the back left corner of the sanctuary is the New Sacristy. Lorenzo de' Medici was attending Mass in the Duomo one April day in 1478 with his brother Giuliano when they were attacked in the infamous Pazzi Conspiracy. The conspirators, egged on by the pope and led by a member of the Pazzi family, old rivals of the Medici, fell on the brothers at the ringing of the sanctuary bell. Giuliano was murdered on the spot -- his body rent with 19 wounds -- but Lorenzo vaulted over the altar rail and sprinted for safety into the New Sacristy, slamming the bronze doors behind him. Those doors were cast from 1446 to 1467 by Luca della Robbia, his only significant work in the medium. Earlier, Luca had provided a lunette of the Resurrection (1442) in glazed terra cotta over the door, as well as the lunette Ascension over the south sacristy door. The interior of the New Sacristy is filled with beautifully inlaid wood cabinet doors.

The frescoes on the interior of the dome were designed by Giorgio Vasari but painted mostly by his less talented student Federico Zuccari by 1579.

Art in Tuscany | Paolo Ucello, Funerary Monument to Sir John Hawkwood

|

|

Paolo Ucello, Funerary Monument to Paolo Ucello, Funerary Monument to

Sir John Hawkwood

Domenico di Michelino, Dante and the

Three Kingdoms

|

The mosaic depicting the Annunciation in the lunette above the Porta della Mandorla in the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, made by the brothers Domenico and David Ghirlandaio, it is one of the finest examples of wall mosaics ever made. The central portion of the mosaic bears the date of 1490. The mosaic's tesserae, primarily of a glassy nature, presents a good state of conservation [3].

In addition to the fresco in the Tornabuoni Chapel in Santa Maria Novella, Ghirlandaio created another Annunciation between 1489 and 1490 using the ancient mosaic technique, which he had learnt from Alessio Baldovinetti and which he had been able to employ when restoring a few old mosaics. There is no lectern in this mosaic version of the Annunciation, though the influence of Leonardo's painting is still felt, particularly in the spatial arrangement - a building on the left behind Mary and a view over a wall to a landscape.

Above the Porta della Mandorla in the Duomo, there still exists this mosaic. Vasari wrote the following comment on it: "Domenico enriched the modern art of working in mosaic infinitely more than any other Tuscan, as his works, though few, amply demonstrate...".

Of this mosaic destined for the Porta della Mandorla Domenico only executed the cartoon, which was probably translated into mosaic by his brother David.

|

|

Mosaic depicting the Annunciation in the lunette above the Porta della Mandorla in the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence |

The Duomo, as if completed, in a fresco by Andrea di Bonaiuto, painted in the 1390s, before the commencement of the dome.

|

|

|

|

Andrea Bonaiuti, Way of Salvation, 1365-68, fresco, Cappella Spagnuolo, Santa Maria Novella, Florence

|

The Duomo

|

|

|

By the beginning of the fifteenth century, after a hundred years of construction, the structure was still missing its dome. The basic features of the dome had been designed by Arnolfo di Cambio in 1296. His brick model, 4.6 metres (15 ft) high 9.2 metres (30 ft) long, was standing in a side aisle of the unfinished building, and had long ago become sacrosanct.[ It called for an octagonal dome higher and wider than any that had ever been built, with no external buttresses to keep it from spreading and falling under its own weight.[5]

The commitment to reject traditional Gothic buttresses had been made when Neri di Fioravante's model was chosen over a competing one by Giovanni di Lapo Ghini. That architectural choice, in 1367, was one of the first events of the Italian Renaissance, marking a break with the Medieval Gothic style and a return to the classic Mediterranean dome. Italian architects regarded Gothic flying buttresses as ugly makeshifts and since the use of buttresses was forbidden in Florence, in addition to being a style favored by central Italy's traditional enemies to the north. Neri's model depicted a massive inner dome, open at the top to admit light, like Rome's Pantheon, but enclosed in a thinner outer shell, partly supported by the inner dome, to keep out the weather. It was to stand on an unbuttressed octagonal drum. Neri's dome would need an internal defense against spreading (hoop stress), but none had yet been designed.

|

|

View from the Piazza della Santissima Annunziata and Giambologna's last statue, of Ferdinando I de' Medici |

The building of such a masonry dome posed many technical problems. Brunelleschi looked to the great dome of the Pantheon in Rome for solutions. The dome of the Pantheon is a single shell of concrete, the formula for which had long since been forgotten. A wooden form had held the Pantheon dome aloft while its concrete set, but for the height and breadth of the dome designed by Neri, starting 52 metres (171 ft) above the floor and spanning 44 metres (144 ft), there was not enough timber in Tuscany to build the scaffolding and forms.[8] Brunelleschi chose to follow such design and employed a double shell, made of sandstone and marble. Brunelleschi would have to build the dome out of bricks, due to its light weight compared to stone and easier to form, and with nothing under it during construction. To illustrate his proposed structural plan, he constructed a wooden and brick model with the help of Donatello and Nanni di Banco and still displayed in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo. The model served as a guide for the craftsmen, but was intentionally incomplete, so as to ensure Brunelleschi's control over the construction.

Brunelleschi's solutions were ingenious. The spreading problem was solved by a set of four internal horizontal stone and iron chains, serving as barrel hoops, embedded within the inner dome: one each at the top and bottom, with the remaining two evenly spaced between them. A fifth chain, made of wood, was placed between the first and second of the stone chains. Since the dome was octagonal rather than round, a simple chain, squeezing the dome like a barrel hoop, would have put all its pressure on the eight corners of the dome. The chains needed to be rigid octagons, stiff enough to hold their shape, so as not to deform the dome as they held it together.

Each of Brunelleschi's stone chains was built like an octagonal railroad track with parallel rails and cross ties, all made of sandstone beams 43 centimetres (17 in) in diameter and no more than 2.3 metres (7.5 ft) long. The rails were connected end-to-end with lead-glazed iron splices. The cross ties and rails were notched together and then covered with the bricks and mortar of the inner dome. The cross ties of the bottom chain can be seen protruding from the drum at the base of the dome. The others are hidden. Each stone chain was supposed to be reinforced with a standard iron chain made of interlocking links, but a magnetic survey conducted in the 1970s failed to detect any evidence of iron chains, which if they exist are deeply embedded in the thick masonry walls. He was also able to accomplish this by setting vertical "ribs" on the corners of the octagon curving towards the center point. The ribs had slits, where platforms could be erected out of and work could progressively continue as they worked up,a system for scaffolding.

A circular masonry dome, such as that of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul can be built without supports, called centering, because each course of bricks is a horizontal arch that resists compression. In Florence, the octagonal inner dome was thick enough for an imaginary circle to be embedded in it at each level, a feature that would hold the dome up eventually, but could not hold the bricks in place while the mortar was still wet. Brunelleschi used a herringbone brick pattern to transfer the weight of the freshly laid bricks to the nearest vertical ribs of the non-circular dome.

The outer dome was not thick enough to contain embedded horizontal circles, being only 60 centimetres (2 ft) thick at the base and 30 centimetres (1 ft) thick at the top. To create such circles, Brunelleschi thickened the outer dome at the inside of its corners at nine different elevations, creating nine masonry rings, which can be observed today from the space between the two domes. To counteract hoop stress, the outer dome relies entirely on its attachment to the inner dome at its base; it has no embedded chains.

A modern understanding of physical laws and the mathematical tools for calculating stresses was centuries into the future. Brunelleschi, like all cathedral builders, had to rely on intuition and whatever he could learn from the large scale models he built. To lift 37,000 tons of material, including over 4 million bricks, he invented hoisting machines and lewissons for hoisting large stones. These specially designed machines and his structural innovations were Brunelleschi's chief contribution to architecture. Although he was executing an aesthetic plan made half a century earlier, it is his name, rather than Neri's, that is commonly associated with the dome.

Brunelleschi's ability to crown the dome with a lantern was questioned and he had to undergo another competition. He was declared the winner over his competitors Lorenzo Ghiberti and Antonio Ciaccheri. His design was for an octagonal lantern with eight radiating buttresses and eight high arched windows (now on display in the Museum Opera del Duomo). Construction of the lantern was begun a few months before his death in 1446. Then, for 15 years, little progress was possible, due to alterations by several architects. The lantern was finally completed by Brunelleschi's friend Michelozzo in 1461. The conical roof was crowned with a gilt copper ball and cross, containing holy relics, by Verrocchio in 1469. This brings the total height of the dome and lantern to 114.5 metres (375 ft). This copper ball was struck by lightning on 17 July 1600 and fell down. It was replaced by an even larger one two years later.

The commission for this bronze ball [atop the lantern] went to the sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio, in whose workshop there was at this time a young apprentice named Leonardo da Vinci. Fascinated by Filippo's [Brunelleschi's] machines, which Verrocchio used to hoist the ball, Leonardo made a series of sketches of them and, as a result, is often given credit for their invention.

Leonardo might have also participated in the design of the bronze ball, as stated in the G manuscript of Paris "Remember the way we soldered the ball of Santa Maria del Fiore".

The decorations of the drum gallery by Baccio d'Agnolo were never finished after being disapproved by no one less than Michelangelo.

A huge statue of Brunelleschi now sits outside the Palazzo dei Canonici in the Piazza del Duomo, looking thoughtfully up towards his greatest achievement, the dome that would forever dominate the panorama of Florence. It is still the largest masonry dome in the world.

The building of the cathedral had started in 1296 with the design of Arnolfo di Cambio and was completed in 1469 with the placing of Verrochio's copper ball atop the lantern. But the façade was still unfinished and would remain so until the nineteenth century.

|

The cupola

|

|

|

Giorgio Vasari was an Italian painter, writer, historian, and architect, who is famous today for his biographies of Italian artists, considered the ideological foundation of art-historical writing.

With the growth of his stature and cultural ambitions when he was compiling and writing this book, the Lives of the Artists, the nature of Vasari's commissions fundamentally altered in the final thirty years of his life, from individual works such as altarpieces to grand enterprises in different media requiring a controlling hand over a large body of assistants. To accomplish these great projects he organized a vast workshop on a scale unprecedented in Florence.

Many of his pictures still exist, the most important being the wall and ceiling paintings in the great Sala di Cosimo I of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, where he and his assistants were at work from 1555, and the frescoes he started inside the vast cupola of the Duomo, completed by Federico Zuccari and with the help of Giovanni Balducci.

|

Giorgio Vasari | The Last Judgment

|

|

Giorgio Vasari, The Last Judgment (detail), 1572-79, fresco, Duomo, Florence

|

Domes, which vault the crossing and altar of countless churches, lend themselves well to being transformed into paintings of the sky. The round shape above our heads seems to open onto a higher world, so that God and the things of heaven become visually present at the church holiest spot.

The Last Judgment in the enormous dome of the cathedral in Florence was painted from 1572 onward. Vincenzo Borghini had drawn up a learned theological program as early as 1570, Giorgio Vasari was responsible for executing it, but he died in 1574. Federico Zuccaro completed the frescoes in 1575-79. High up in the fresco in the dome, around the cupola, hovers a temple with the twenty-four elders of the Apocalypse; beneath this, on terraced registers, follow choirs of angels with the instruments of the Passion, then groups of saints, then personifications of the gifts of the Holy SXpirit, of the virtues, and of the beatitudes, and finally the regions of hell with various deadly sins. The composition of the fresco thus takes into account the architectonic form of the vault in its eight sections, hard upon one another. There is no attempt to dissolve the architectural structure completely by means of illusionistic painting.

The temple and the zones of heaven for four of the eight sections of the vault were completed under Vasari's direction.

Art in Tuscany | Giorgio Vasari and Italian Renaissance painting |

|

The spectacular composition is organized in four strips, while the fifth is occupied by a false loggia from which gigantic prophets look down

|

|

|

|

|

|

Giorgio Vasari, The Last Judgment (detail), 1572-79, fresco, Duomo, Florence

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The Façade

|

|

|

|

Santa Maria del Fiore as it appears in the fifteenth-century Codex Rustici, Florence, 1447

The original façade was only completed in its lower portion in the fifteenth century and then left unfinished.

|

The original façade, designed by Arnolfo di Cambio and usually attributed to Giotto, was actually begun twenty years after Giotto's death.

A mid-15th century pen-and-ink drawing of this so-called Giotto's façade is visible in the Codex Rustici, and in the drawing of Bernardino Poccetti in 1587, both on display in the Museum of the Opera del Duomo. This façade was the collective work of several artists, among them Andrea Orcagna and Taddeo Gaddi. This original façade was only completed in its lower portion and then left unfinished. It was dismantled in 1587-1588 by the Medici court architect Bernardo Buontalenti, ordered by Grand Duke Francesco I de' Medici, as it appeared totally outmoded in Renaissance times. Some of the original sculptures are on display in the Museum Opera del Duomo, behind the cathedral. Others are now in the Berlin Museum and in the Louvre. The competition for a new façade turned into a huge corruption scandal. The wooden model for the façade of Buontalenti is on display in the Museum Opera del Duomo. A few new designs had been proposed in later years but the models (of Giovanni Antonio Dosio, Giovanni de' Medici with Alessandro Pieroni and Giambologna) were not accepted. The façade was then left bare until the 19th century.

In 1864, a competition was held to design a new façade and was won by Emilio De Fabris (1808–1883) in 1871. Work began in 1876 and completed in 1887. This neo-gothic façade in white, green and red marble forms a harmonious entity with the cathedral, Giotto's bell tower and the Baptistery, but some think it is excessively decorated.

The whole façade is dedicated to the Mother of Christ.

Main portal

The three huge bronze doors date from 1899 to 1903. They are adorned with scenes from the life of the Madonna. The mosaics in the lunettes above the doors were designed by Niccolò Barabino. They represent (from left to right): Charity among the founders of Florentine philanthropic institutions, Christ enthroned with Mary and John the Baptist, and Florentine artisans, merchants and humanists. The pediment above the central portal contains a half-relief by Tito Sarrocchi of Mary enthroned holding a flowered scepter. Giuseppe Cassioli sculpted the right hand door.

On top of the façade is a series of niches with the twelve Apostles with, in the middle, the Madonna with Child. Between the rose window and the tympanum, there is a gallery with busts of great Florentine artists.

|

|

Santa Maria del Fiore, Codex Rustici, Florence, 1447, conserved in the Archepiscopal Seminary

|

Baptistery of San Giovanni

|

|

|

|

Mosaic ceiling

|

Dating back to the 11th century, the Baptistery is thought to be the oldest building in Florence. It is certainly one of the most revered, generations of Florentines have been baptised here, including Dante, who called it Il Mio Bel San Giovanni.

In Christian architecture, the baptistery was so-called because baptisms were to be performed there, quite often meaning it was a separate building from the cathedral. Baptisteries were commonly created with eight sides to symbolise the Eighth Day, an unmeasureable time in a seven day week and the day of Christ's Resurrection, which is fitting as a baptism is considered a form of “rebirth.” Florence's Baptistery for centuries was believed to have been originally a Roman temple dedicated to Mars, but was actually originally built around the 4th or 5th century, replaced by a Christian baptistery in the 6th century. Roman ruins including a monochrome mosaic pavement of what is thought to have been a residence, still lie underneath.

The 16th century artist and biographer, Giorgio Vasari, said that entering the Baptistery was to enter into the remote past of the city, as it is filled with so many references to Florence's antique past in its forms, mosaics and structure. Here the past is truly “reborn.”

Until the end of the 19th century, all Catholic Florentines were baptised in San Giovanni including important figures such as the poet Dante Alighieri and members of the Medici family. In the Middle Ages, baptisms were performed on the 25th of March each year (the Florentine New Year) and the number of boys and girls were counted by dropping a black bean for each boy and a white bean for each girl into two large urns held inside the baptistery.

Florence's baptistery is dedicated to St John the Baptist, the city's beloved Patron Saint. Even in the Middle Ages, they had his image on their coin, the fiorino, the first minted coin in Europe to be accepted as stable international currency. St John the Baptist's Day, June 24th, is still celebrated with many Florentines taking the day off, shops closing, and celebrations in the form of fireworks and the calcio storico (a historic football game), all in honour of St John the Baptist.

The current Romanesque style baptistery, sitting opposite the Duomo of Santa Maria del Fiore, was constructed between 1059 and 1128, built, according to legend, with marble brought from the recently conquered town of Fiesole together with other ancient Roman structures. The building is nowadays most famous for its three sets of bronze doors, decorated with relief sculptures by two of the early Renaissance's most important figures: Andrea Pisano, who designed the southern doors, and Lorenzo Ghiberti, who did both the north and east doors. Ghiberti's eastern gold-gilded doors, which face the façade of the Duomo are perhaps better known as “The Gates of Paradise”, nicknamed by Michelangelo later in the century who thought they were so beautiful they could be the gates to Heaven.

Florence | The Nuova Cronica | The Villani Chronicle

Brunelleschi's enormous dome of the cathedral can either be admired from the ground, from the bell tower or by ascending the 460 steps to the top for a panorama of the city.

Opening times: 12:15pm - 7pm Monday to Saturday, except the 1st Saturday of the month when the hours are 8:30am - 2pm; 8:30am - 2pm Sundays and public holidays. Closed New Year's day, Easter Sunday, September 8, Christmas day.

|

|

The Villani Chronicle, How the city of Florence was destroyed by Totila, the scourge of God, king of the Goths and Vandals, ms. Chigiano L VIII 296 della Biblioteca Vaticana, f.36r (1.III,1) The Villani Chronicle, How the city of Florence was destroyed by Totila, the scourge of God, king of the Goths and Vandals, ms. Chigiano L VIII 296 della Biblioteca Vaticana, f.36r (1.III,1)

|

Ghiberti's doors are often considered one of the most influential works of the Renaissance. Ghiberti used many different techniques including ancient Roman lost-wax casting techniques, etching and use of Donatello's relief sculpture techniques – with a great use of perspective, forms in the background are barely etched into the bronze, while figures in the foreground are fully rendered, seemingly coming out at you. Many of the panels have a narrative content where several different scenes from the same story take place throughout the background, midground and foreground of the panels, a very popular technique of story-telling in Renaissance art.

It took years for Ghiberti to complete the doors, who began them as a young man after being selected over artists such as Donatello and Filippo Brunelleschi. The doors were finally completed in 1452, when Ghiberti was seventy-four years old, just a few years before his death. He left a small signature in one of the twenty-four heads carved into roundels – one of them, around eye level, is his selfportrait (pictured above right), together with some other family portraits. Giorgio Vasari decided the doors were “undeniably perfect in every way and must rank as the finest masterpiece ever created.”

The stories depicted in each panel of Ghiberti's Gates of Paradise are from left to right, top to bottom:

1. Adam and Eve 2. Cain and Abel 3. Noah 4. Abraham 5. Isaac with Esau and Jacob 6. Joseph 7. Moses 8. Joshua 9. David 10. Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

When the disastrous flood of 1966 swept five of the heavy, original bronze panels off the door frames, measures were taken to restore the doors and replace the originals, which were still on the Baptistery all these centuries. They can now be found in the collection of the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, behind the cathedral.[4]

|

|

East doors, or Gates of Paradise, by Lorenzo Ghiberti |

The Campanile | Giotto's Tower

|

|

|

|

The Campanile | Giotto's Tower

|

To the south of the Cathedral stands the elegant campanile or bell tower. Work began on the free-standing structure in 1334 and the design was entrusted to Giotto. The campanile is generally referred to as Giotto's Tower, in spite of the fact that the building had only reached the height of the first story when he died in 1337. Andrea Pisano became the Capomaestro or Head of Works and continued Giotto's design on the second story before changing it by dividing the four sides with pilasters. A decade later Pisano moved on to a better position in Orvieto and the post fell vacant. In 1352 Francesco Talenti was appointed to the position and he made his mark by altering the design once more, adding the twin Gothic windows surmounted by a single Gothic window in the final story.

The tower was finally completed in 1359 and rises to a height of 280 feet (85m.).

The first two storeys of the tower are decorated with a series of diamond and hexagonal reliefs from the workshop of Andrea Pisano. They illustrate the evolution and salvation of mankind, a theme which is often found on the facades of medieval churches, but is unusual on the facade of a bell tower. (The original reliefs, which can be seen in the cathedral museum, have been replaced by copies).

The entrance to the campanile is on the east side and dates back to 1431. Prior to this, the tower was directly connected to the cathedral by means of a footbridge.

Museo dell'Opera del Duomo

The Museo dell'Opera del Duomo was originally a Cathedral workshop founded in 1296 to oversee construction of the Florence Cathedral and the Giotto Bell Tower. The museum exists mainly to house the sculptures removed from the niches and doors of the Duomo group for restoration and preservation from the elements.

The courtyard is enclosed to show off — under natural daylight, as they should be seen — Lorenzo Ghiberti's original gilded bronze panels from the Baptistery's Gates of Paradise, which are being displayed as they're slowly restored. Ghiberti devoted 27 years to this project (1425-52), and you can now admire up close his masterpiece of schiacciato (squished) relief — using the Donatello technique of almost sketching in perspective to create the illusion of depth in low relief.

On the way up the stairs, you pass Michelangelo's Pietà (1548-55), his second and penultimate take on the subject, which the sculptor probably had in mind for his own tomb. The face of Nicodemus is a self-portrait, and Michelangelo most likely intended to leave much of the statue group only roughly carved, just as we see it. Art historians inform us that the polished figure of Mary Magdalene on the left was finished by one of Michelangelo's students, while storytellers relate that part of the considerable damage to the group was inflicted by the master himself when, in a moment of rage and frustration, he took a hammer to it.

The top floor of the museum houses the Prophets carved for the bell tower, the most noted of which are the remarkably expressive figures carved by Donatello: the drooping, aged face of the Beardless Prophet; the sad, fixed gaze of Jeremiah; and the misshapen ferocity of the bald Habakkuk (known to Florentines as Lo Zuccone — pumpkin head). Mounted on the walls above are two putty-encrusted marble cantorie (choir lofts).

The slightly earlier one (1431) on the entrance wall is by Luca della Robbia. His panels (the originals now displayed at eye level, with plaster casts set in the actual frame above) are in perfect early Renaissance harmony, both within themselves and with each other, and they show della Robbia's mastery of creating great depth within a shallow piece of stone. Across the room, Donatello's cantoria (1433-38) takes off in a new artistic direction as his singing cherubs literally break through the boundaries of the "panels" to leap and race around the entire cantoria behind the mosaicked columns.

The room off the right stars one of Donatello's more morbidly fascinating sculptures, a late work in polychrome wood of The Magdalene (1453-55), emaciated and veritably dripping with penitence. |

|

|

The Archconfraternity of the Misericordia, opposite the Baptistery, in the Loggia on the corner between Piazza San Giovanni and Via Calzaiuoli, was founded in the 13th century, during the period of the really ferocious battles between the Guelphs and Ghibellines for the control of the government of the Republic. However its development was also linked to the battle of the Church against the "Patarine" heretics, who were instead supported by the Ghibellines to weaken the papacy.

The meantime the Confraternity of the Misericordia merged (1425) for a while with the Company of the Bigallo until their separation in 1490. It also changed the colour of its robes from red to black (1497) and set up its permanent headquarters (1576) in a palace that was donated by the Grand Duke Francesco I de' Medici and stood on the opposite corner of Via Calzaiuoli, facing Giotto's Belltower.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

[1] The Front Façade of Santa Maria del Fiore, Duomo of Florence | Arnolfo di Cambio designed the original façade of the Duomo. The design drawings of the façade are in the Museum of the Opera del Duomo. This original façade was only completed in its lower portion in the fifteenth century and then left unfinished.

In 2005, a model of this façade was placed in the Museum. Some statues from this façade are in the Museum.

Grand Duke Cosimo I ordered that the façade be dismantled in 1587-1588. A competition was held for a new façade but the competition came to nothing amid allegations of corruption.

The façade was then left bare until the 19th century.

Visitors on a Grand Tour of Europe visiting Florence would have been faced with the bare façade.

In 1864 a competition was held to design a new façade. It was won by Emilio De Fabris (1808-1883) in 1871. Work was begun in 1876 and completed in 1887. This neo-gothic façade in white, green and red marble forms a harmonious entity with the cathedral, Giotto's belltower and the Baptistery.

The whole façade is dedicated to the Mother of Christ. On the side of the Cathedral facing the Campanile, the 14th century facade, created by Andrea Pisano, Francesco Talenti and Andrea di Cione di Arcangelo (Orcagna), is still intact.

[2] Filippo Brunelleschi was born in Florence in 1377, and died here in 1446. Of him Vasari wrote: "He was given to us by Heaven to give new form to architecture". Inside the Cathedral is a portrait medallion, beneath which his tomb was located. Outside the Cathedral is the sculpture by Pampaloni, portraying him next to Arnolfo di Cambio. Brunelleschi is famous for having built the dome of Florence Cathedral, and for the innovative techniques by which he adapted classical forms to the spirit of his own times.

In 1401 he took part in the famous public competition (won by Ghiberti) for the commission to make the Baptistery doors; his gilded bronze panel of the Sacrifice of Isaac may be seen in the Bargello. In the church of Santa Maria Novella we can see his wooden Crucifix (1418-20)in the Gondi Chapel. He studied the science of perspective and there are panels showing the Baptistery and Piazza Signoria. In 1417 he began work on the dome, kept him fully occupied for twenty years. This dome became the focus of great hope for the future and a symbol for all Florentines; Leon Battista Alberti wrote that it seemed to cover with its shadow all the people of Tuscany. In the Opera del Duomo Museum there are wooden models and building materials associated with the dome's construction. In 1419 Brunelleschi was commissioned by the Silk Guild to design the Foundling Hospital of the Innocenti, which with the harmonious perspective geometry of its loggia is the first masterpiece of renaissance architecture. T he Piazza Santissima Annunziata, which it flanks, later became one of the most admired urban spaces in Europe. From here we proceed to the church of San Lorenzo (begun in 1419), whose luminous interior and nobility of form recall the basilicas of antiquity. In the centrally-planned Old Sacristy there is an evident spatial dialogue between the sphere and the cube, and an architectural language derived from the classical world. On our way to Santa Croce we pass the Palagio del Parte Guelfa, which Brunelleschi improved: he designed the council hall on the first floor, and the delicately moulded classical window frames outside. Next to Santa Croce we come to the Pazzi Chapel, begun in 1430, a centrally-planned space with a hemi-spherical dome over barrel vaulting, its white plaster walls contrasting with the grey stone of the pilasters and entablature. Brunelleschi's last great project was the church of Santo Spirito (begun 1436), preceded by the Rotonda of Santa Maria degli Angeli (c. 1434), not far from the Foundling Hospital, which was never finished but clearly shows the influence of classical centrally-planned buildings. Brunelleschi had intended that the façade of Santo Spirito should face the Arno, but this scheme was altered; so too was his plan to express the curved shape of the side chapels by an undulating exterior, and his idea of having four doors instead of the traditional three; these changes were made by the architects who completed the church after Brunelleschi's death. The design of Palazzo Pitti is also attributed to Brunelleschi, though it was considerably modified in later times by the Medici Grand Dukes.

[3] Science and technology for cultural heritage | www.mendeley.com

Presents the data obtained from a study of the alterations and chemical composition of some of the vitreous tesserae in the mosaic depicting the Annunciation in the lunette above the Porta della Mandorla in the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence (Italy). Made by the brothers Domenico and David Ghirlandaio, it is one of the finest examples of wall mosaics ever made; the central portion of the mosaic bears the date of 1490.

[4] Due to its geographical location, Florence has often been the victim of flooding. The 1844 flood has left a particularly lasting memory, even though the peak of the flooding remained significantly below the peak recorded on November 4, 1966.

The staggering damage to the famous Ponte Vecchio illustrates the extent of the flood catastrophe. The washed over riverbanks, the destruction of the bridges over the Arno River, rubble, refuse, and mud at the Uffizi Gallery and in the quarters of the city close to the river all document the enormous efforts of the helpers who came to the city on the Arno directly after the flood: Soldiers untiringly attempt to remove the mud from the interior of a church; Innumerable volunteers, admiringly and gratefully named the ‘Angeli del fango – angels of the mud’, help to rescue the art treasures.

Art in Tuscany | Cimabue, the Crucifix of Santa Croce at Florence

[5] 'The construction of the dome of Florence Cathedral (was) one of the germinal events of Renaissance architecture...The problem had been posed in the middle of the fourteenth century when the definitive plan for the octagonal crossing had been laid down. The diameter of the dome at 39.5 metres (130 feet) precluded the traditional use of wooden structuring to support the construction of the vault, while the use of buttresses as in northern Gothic cathedrals was ruled out by the building's design.'

[

Michael Raeburn, ed. Architecture of the Western World, p 130, 1988.]

|

|

Giacomo Brogi (1822-1881) - "Florence. Giotto bell-tower". Ca. Before 1865

View onto the Baptistery and the Loggia del Bigallo (Photographer Bazzechi) View onto the Baptistery and the Loggia del Bigallo (Photographer Bazzechi)

|

This page uses material from the Wikipedia article Florence Cathedral , published under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Santa Maria del Fiore (Florence).

|

Podere Santa Pia, un’oasi di pace immersa nel verde delle colline della Maremma, è un’antica struttura completamente ristrutturata cercando di mantenere inalterate le stupende caratteristiche dell’immobile originario.

Sulle splendide e verdeggianti colline dell’alta Maremma, a 300 mt sul livello del mare, sorge il paese di Cinigiano. Qui si trova Podere Santa Pia, una casa vacanze accogliente, spaziosa e confortevole per gruppi da 2 a 13 persone. La posizione è ideale per una vacanza di riposo e per chi vuole conoscere le città d'arte.

Case vacanza in Toscana | Podere Santa Pia

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Wandelen in de omgving van de Duomo Piazza Signoria

|

|

|

Begin begint op de Piazza del Duomo, het religieuze centrum van Firenze, waar de Duomo , de doopkapel, het bisschoppelijk paleis en de klokkentoren van Giotto zich bevinden. De eerste kathedraal van de stad bevond zich buiten de stadsmuren. Het was de San Lorenzo kerk, die werd gebouwd in de 4e eeuw. In de VII eeuw werd de titel van " Kathedraal " doorgegeven naar Santa Reparata die in 1296 werd herbouwd als Santa Maria del Fiore. Dit is de Duomo zoals we die vandaag kennen. In deze periode werd het religieuze centrum gescheiden van het openbare centrum door de bouw van het Palazzo Vecchio (Palazzo della Signoria .

Op de hoek met de Via Calzaioli kunt u de Loggia del Bigallo bewonderen, een marmeren elegante loggia die door Ambrogio di Rienzo (1358 1353) ontworpen werd.

De Bigallo Madonna della Misericordia met de oudste bekende afbeelding van Firenze. We zien het Baptisterum en een interessant zicht op de bouw van Santa Maria della Fiora. Ook de oude kathedraal van Santa Reparata, met zijn klokkentoren en zadeldak, delen van Giotto's Campanile en de gevel van Santa Maria del Fiore, zoals hij door Arnolfo ontworpen werd, zijn nog te zien. Het fresco werd geschilderd 1342.

Wandelen in Toscane | Firenze | Quarter Duomo and Signoria Square (eng)

|

|

De Bigallo Madonna della Misericordia, school van Bernardo Daddi, 1342.

|

From Piazza del Duomo to Santa Croce

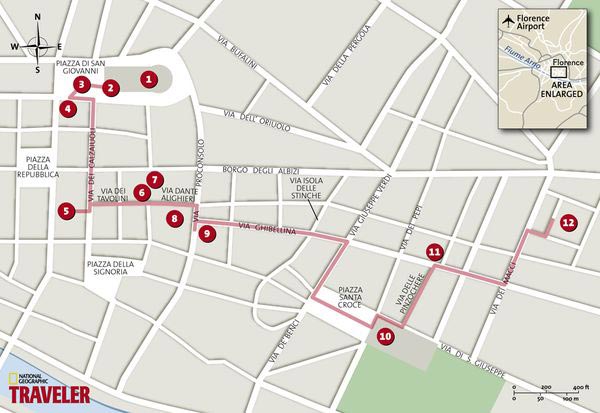

Piazza del Duomo marks Florence’s religious heart, home to the (1) Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (the Duomo) (www.duomofirenze.it); the 14th-century (2) Campanile, or "bell tower"; and the (3) Battistero, or Baptistery. Visit all three before starting this walk, which explores the city’s medieval eastern quarter, a maze of small streets and half-hidden churches rich in historical associations.

Walk south from the piazza on the pedestrian-only Via dei Calzaiuoli, one of the city’s main thoroughfares, noting the pretty (4) Loggia del Bigallo on the right as you exit the square: It was built by a charitable foundation in the 1350s and formed part of an orphanage established by the foundation.

Visit the church of (5) Orsanmichele, midway down Via dei Calzaiuoli on the right at the corner of Via de’ Lamberti (the entrance is to the rear). It is known for its medieval niche statues and for a lovely interior dominated by a grand 14th-century tabernacle and a painting of the Madonna delle Grazie (1347) by Bernardo Daddi.

Almost opposite the church, take Via dei Tavolini and then Via Dante Alighieri. You are now in a district closely associated with the great Florentine poet, Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), author of The Divine Comedy. In the vicinity are the (6) Casa di Dante, or House of Dante (corner of Via Dante Alighieri and Via Santa Margherita; www.museocasadidante.it), a small museum devoted to the poet; (7) Santa Margherita, at Via Santa Margherita, near the corner with Via del Corso, the church where the poet may have married; and the (8) Badia Fiorentina, (go down Via Dante Alighieri and make a right on Via del Proconsolo), the parish church of Beatrice Portinari, Dante’s lifelong muse.

At the Badia, turn right on Via del Proconsolo to the (9) Bargello, directly across the way at Via del Proconsolo 4, once Florence’s medieval police headquarters, prison, and place of execution. Today it houses the cream of Florence’s medieval, Renaissance, and baroque sculpture, as well as numerous beautiful salons devoted to the decorative arts.

East of the Bargello you can meander almost at random, getting happily lost in the old streets en route to the 13th-century church of (10) Santa Croce in Piazza Santa Croce. The best route is down Via Ghibellina, if only because near its conclusion, a tiny right turn, Via Isola delle Stinche, takes you to the Il Gelato Vivoli (on the right at No.7R), widely considered to be Italy’s best ice cream.

Santa Croce is equally mouthwatering; the must-see church in Florence, thanks to numerous important early frescoes by Giotto and others, along with the tombs of some of the city’s most illustrious men and women, including Michelangelo, Machiavelli, and Galileo.

Few visitors venture beyond Santa Croce, but the Sant’Ambrogio district to the north and east is worth the extra effort. Take Via delle Pinzochere off the north side of Piazza Santa Croce to the (11) Casa Buonarroti, (Via Ghibellina 70 near Via Michelangelo Buonarroti), a stylish museum devoted to Michelangelo.

Walk east from the museum on Via Ghibellina and turn left on Via dei Macci. A short way up on the right is the (12) Sant’Ambrogio market, focus of an increasingly chic neighborhood of cafés and specialty stores.

|

|

Circular Renaissance footpath in the Florentine hills

The ‘Anello del Rinascimento’ is a circular footpath over 170kms long which winds its way through the Florentine countryside. It circles the city and Filippo Brunelleschi’s dome which is at its heart

This footpath passes through woods and farmland and passes monasteries, castles and ancient churches, as well as entering the heart of Florence, Fiesole and other nearby Tuscan towns.

The route:

Start from Piazza Buondelmonti, site of the Basilica of Impruneta, and cross through the centre of the old town along Via Paoleri and Via Roma until Villa Carrega. From here there is a wonderful panoramic view towards Poggio Firenze, the Chianti hills, the Apennine mountain chain and Pratomagno mountain. From here go on to the village of Desco and Viale (Avenue) Aldo Moro. Bear right along the road that heads towards Florence and which goes through Pozzolatico. After approximately 1km, bear left and go up (look out for the strange house on the corner) on Via di San Miniato in Quintole. The street is asphalted at first and rises steeply to become a dirt track which leads to the ancient and beautiful church of the same name. Next to the church is an old cemetery. The track continues through an olive grove and is partly asphalted. It heads to the village of I Baruffi. At the fork in the road where there are some modern villas, bear right and go down Via le Rose towards the village – after which there is the stunning Antinori Villa. Turn right after the villa and pass by the villa’s formal cypress-lined driveway and take the ‘white road’ (dirt rack covered with white/grey stones) which has a wonderful view over Certosa. Carry on through the olive grove and you will reach the last rural residence. Turn left just a few metres before and go down to the car park at Bottai, on the Cassia main road. (Attention: on the track between the last residence and the car park there is a sign which reads ‘cancello chiuso - strada privata’ [locked gate – private road]. Don’t be fooled, this road is actually open to the public!). Just before the car park there is a closed gate: one hundred metres before you must take a left and hop over a low wall to get to the car park. To get to Certosa, turn right on the Cassia road towards Florence. After around one hundred metres turn left into Via di Colleramole and then right into Via Buca della Certosa. Once you arrive in the centre of Certosa go up the road on the left which is the old stone Via Scalinata that leads to the ancient entrance of the religious building.

Be sure not to miss the Certosa (Carthusian monastery) del Galluzzo di Firenze. It is structured like a feudal castle and its exterior makes it look more like a fortress rather than a place of worship. The Certosa di Galluzzo di Firenze is run by Cistercensi monks, not by Carthusian monks, who give free guided tours.

[Official Tourism Site of Tuscany by intoscana.it]

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()